French GP, Rouen 1968…

It has the feel of final practice/qualifying about it doesn’t it? The wing in the foreground is either Jacky Ickx’ winning Ferrari 312 or Chris Amon’s sister car.

Graham Hill stands patiently at left whilst the mechanics make adjustments to his car with Lotus boss Colin Chapman leaving the boys to it, resting against the pit counter.

At far left, obscured, Jack Brabham is being tended to in his Brabham BT26 Repco 860 V8. Jochen Rindt popped his BT26 on pole proving the car had heaps of speed if not reliability from its new 32-valve, DOHC V8. The speedy Austrian took two poles with it that year.

The dude in the blue helmet is Jackie Oliver who is about to have the mother and father of high speed accidents when wing support failure saw him pinging his way through the French countryside, clobbering a set of chateau gates and dispensing aluminium shrapnel liberally about the place at around 125 mph. He survived intact – shaken but not stirred you might say. It wasn’t the last of his career ‘big ones’ either. Click here; https://primotipo.com/2017/01/13/ollies-trolley/

In the distance is Goodyear blue and white striped, jacket wearing Tyler Alexander so there must be a couple of McLaren M7As down that way.

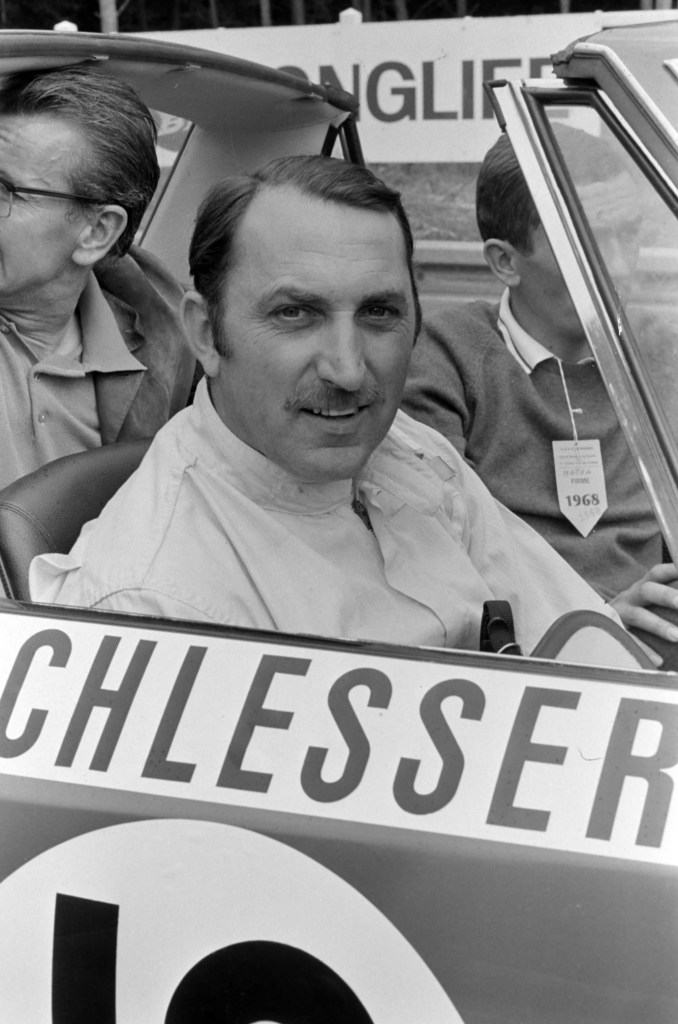

Ickx won a tragic wet race in which French racer Jo Schlesser died on lap two when he lost control of the unsorted Honda RA302 in the fast swoops past the pits, burned alive in the upturned car, it was a grisly death. Ickx’ first GP win, no doubt was memorable for the Belgian for all of the wrong reasons. He won from John Surtees, below, in the conventional Honda RA301 V12 and Jackie Stewart’s Matra MS10 Ford.

Surtees did not have a great Honda season retiring in eight of the twelve GPs, his second place at Rouen and third at Watkins Glen were the two high points of the season.

Honda withdrew from GP racing at the end of the year “to concentrate their energies on developing on new road cars (S360, T360 and S500), having cemented the Honda name in the motorsport hall of fame.” A racing company to its core, its interesting how Honda still use racing past and present to differentiate themselves from other lesser marques: https://www.honda.co.uk/cars/world-of-honda/past/racing.html

Click on this article for a piece on the 1968 French GP and also the evolution of wings in that period; https://primotipo.com/2016/08/19/angle-on-the-dangle/

Jo Schlesser and the Honda RA302…

You would have to have a crack wouldn’t you?

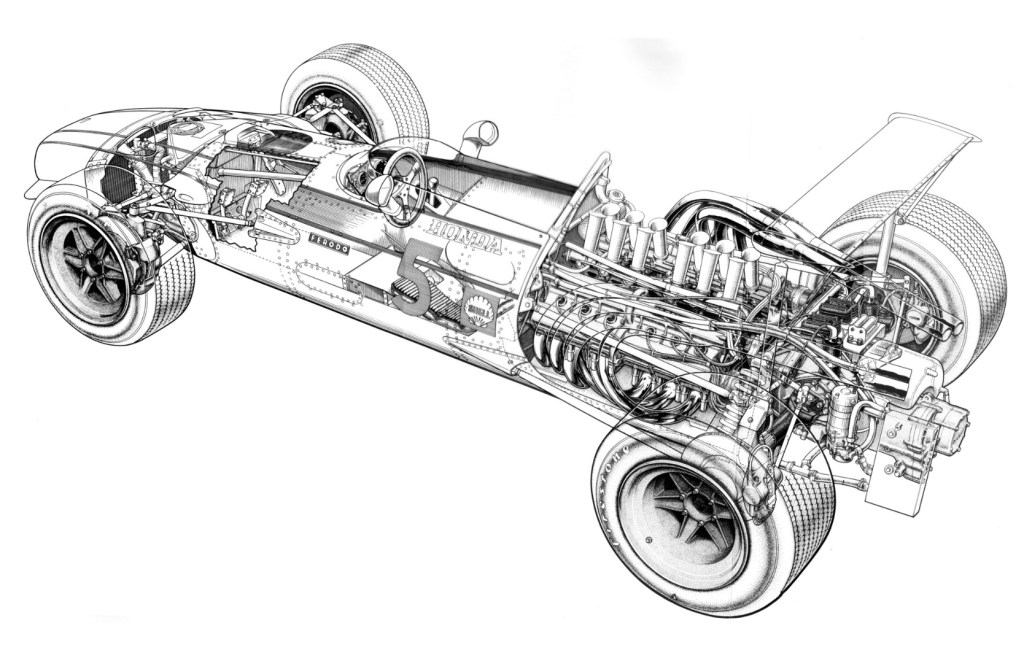

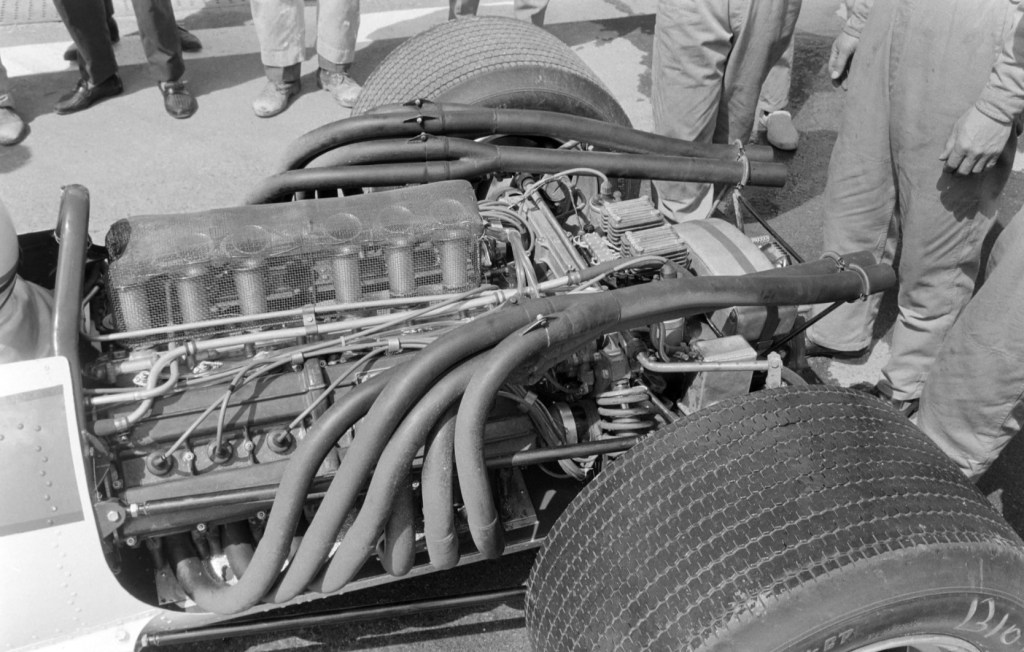

The offer of a works car (Honda RA302 #in your home Grand Prix, however badly your vastly experienced team leader felt about the radical magnesium chassis, 3-litre (88mm x 61.4 mm bore/stroke, four-valves per cylinder -torsion bar sprung – 2987cc) 120-degree air-cooled V8 machine would have been too much to resist?

The new car bristled with innovation, including the mounting of the engine, which was in part located via a top-boom extension of the monocoque aft of the rear bulkhead. This approach was adopted by the Mauro Forghieri led team which designed the Ferrari ‘Boxer’ 312B in 1969, one of the most successful 1970 F1 machines.

And so it was that poor, forty years old, Jo Schlesser died having a red hot go after completing only 12km of the race.

Denis Jenkinson looks on, above, as Schlesser prepares for the off during practice, the look on the great journalists face says everything about his interest in this new technical direction. The car behind is Richard Atwood’s seventh placed BRM P126 V12.

Douglas Armstrong wrote of the Honda RA302 as follows in his review of the 1968 Grand Prix season published in Automobile Year 16. “Although it was ill-fated the car was immediately recognised as a new and formidable approach to Formula-1 racing.”

“Taking a leaf from the Porsche air-cooling technique, Honda had mounted a large oil-tank behind the right of the driver, and this was meant to dissipate much of the engine heat. On each cockpit side was a light-alloy scoop to convey air to the engine, and the sparking plugs were also duct enclosed for cooling. To the left of the drivers head another scoop took cooling air into the crankcase where it became involved with oil mist and was then drawn out by a de-aerator which retained the oil but expelled the air from a vent on top of the magnesium backbone.”

A magnesium monocoque chassis supported the unstressed, fuel injected V8 which is variously quoted at between 380-430bhp at this early stage of its development, I am more at the conservative end of that range.

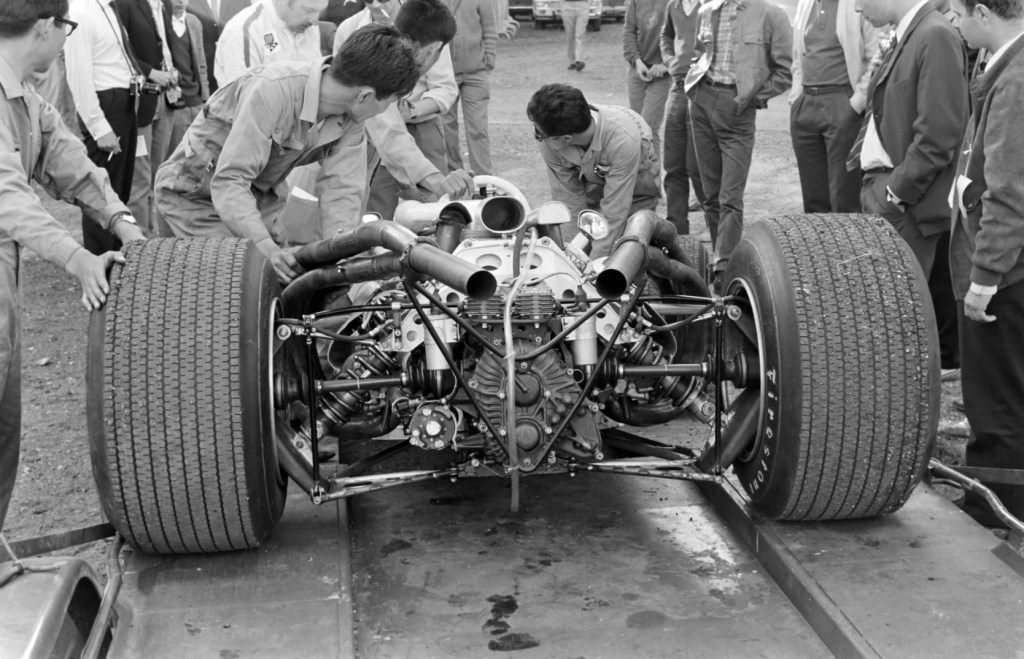

Inboard rocker front suspension and outboard at the rear, note the ‘boxed’ inboard lower inverted wishbones, single top link and two radius rods. As Doug Nye noted, “The suspension was the only conventional part of this wholly Japanese designed and built new comer.”

All the attention to weight saving and compactness – the Lotus 49 Ford DFV would have been very much top-of-mind in Japan – resulted in a car “reportedly weighing close to the minimum requirement of 1102lb.”

Politics and priorities…

John Surtees tested another RA302 (chassis #F-802 remains part of the Honda Collection) during the Italian GP weekend at Monza in September but declined to race the car, that chassis still exists. Instead Il Grande John put his RA301 V12 on pole!

Lola’s Derrick White developed an evolution of the ’67 Honda RA300 for 1968, the lighter, but still 649kg, RA301 was blessed with a 430bhp Honda V12. Let’s not forget these Hondolas spun out of, or off Lola’s very successful 1966 T90 ‘Indycar’.

A careful review of the year reveals a better performing car than the results suggest. Surtees was second at Rouen, third at Watkins Glen and fifth in the British GP at Brands Hatch despite a broken rear wing. Elsewhere, he ran well in Spain and at Monaco until the gearbox failed, then led at Spa and set fastest lap before a rear wishbone mount broke. At Zandvoort he was delayed by wet ignition, then alternator trouble ended his run. In a notable wet season, he was impacted by wet ignition and then overheating caused by a long delay before the start. Surttes started from pole at Monza, then led, and crashed…He was up-there in Canada until gearbox failure , then led after the start in Mexico before falling back and retiring with overheating.

MotorSport wrote that the the ill-fated debut of the Honda RA302 took place against a background of strong opposition from Surtees. He had been expecting an improved V12 for the RA301 – a lighter 490bhp V12 with conventional power take-off at the rear of the engine – and was therefore surprised when the all-new RA302 was delivered to Honda’s UK base at Slough. Its 120-degree air-cooled V8 was a mobile test bed to showcase the technology Soichiro Honda was to use in his new road cars; remember the sensational air-cooled Honda 7 and 9 Coupes of the early 1970s for example?

“I tried it at Silverstone,” recalls Surtees. “You’d drive out of the pits and it would feel quite sharp, but it was impossible to drive any distance with it performing as it should. Mr Nakamura told Japan we could not take this to a race.”

During that Silverstone test, the car ran for only two laps before the oil blew out, even after modifications it still wouldn’t go far because the engine overheated rapidly. John refused to race it – not unreasonably given the pace of the RA301 – before further tests could proved its speed and endurance. In addition Surtees suggested they build an aluminium version to replace the flammable magnesium chassis machine.

When Honda arrived at the French GP in 1968, the French arm of Honda urged the team to race the new RA302 to promote its small but growing range of cars. Soichiro Honda was in France on a trade mission that week and, doubtless influenced by his local representatives, he decided to enter the RA302 under the Honda France banner, with Schlesser as the driver.

Surtees, and even team boss Nakamura, didn’t know of the plan until 7.30am on the Thursday, the first day of practice. “It was not run by the existing Honda team,” says John, “but people who’d previously worked with us were brought over from Japan. They worked as a totally separate unit” to the guys looking after Surtees V12 engined RA301.

Surtees shed no light as to the cause of Schlesser’s crash, but acknowledges the circuit is tricky at the site of the accident, describing it as “the sort of place on the circuit where you were fully occupied”.

It is thought a misfire or complete engine cut-out caused Schlesser to lose control. Honda acquired film showing him getting into a ‘tank-slapper’ before going off – but there were never any official conclusions. Engine designer and future Honda boss Nobuhiko Kawamoto was in Japan that weekend. “I thought the cause may have been a transmission seizure,” he says. “After three months, the residuals came back, small amounts of steel parts, the engine and transmission, but we found it was really clean. The cause was not revealed.”

Surtees would briefly drive a second RA302 in practice at Monza, but by then it was academic.

With Soichiro Honda present, Surtees refused to race it and the popular 40 year old, very experienced single seater and sportscar driver, was appointed to drive the new car. Unfortunately, Surtees’ doubts were proven true, when Schlesser lost control of the car in the downhill sweepers and crashed. The car overturned and caught fire. The full fuel tank and magnesium chassis burned so intensely that nothing could be done to save Schlesser. He became the fourth F1 driver to die that season (after Jim Clark, Mike Spence and Lodovico Scarfiotti).

“The episode of that car and the accident brought Honda’s whole Formula One programme to an end,” says John. “The fact that it didn’t work meant there weren’t the resources to go back to what we were originally going to do.”

“When you add up how far we progressed (in 1968) on a very limited budget we didn’t do too badly. If you add up how competitive we were and of we hadn’t had the silly problems, we could have been champions that year,” Surtees said to David Tremayne.

“Derrick White had drawn up a good chassis and Nobohiko Kawamoto had promised us a new lightweight 490bhp V12engine and gearbox for 1969.” The increasing focus on emissions and the road cars obliged Honda to cut their budget, and the F1 project was cancelled.

Surtees, “I understood why of course, but I really believe that Honda’s later situation in Formula 1 could have come sooner. The 301 was the right car, and with the new engine and gearbox it would have been shorter and much lighter…Instead it was a case of what might have been…”

Tremayne wrote, “Many years later when Honda were winning championships with Williams, Honda Motor Company boss Tadashi Kume – who had been a senior engineer on the RA301 in 1968 – sent Surtees a telegram which said in part, “None of this would have been possible without your investment.”

Credits…

Getty Images, oldracingcars.com, ‘History of The Grand Prix Car 1966-85’ Doug Nye, MotorSport, David Tremayne ‘Honda’s First F1 Chapter’ in hondanews.eu

Tailpiece…

Jo, drivers parade immediately before the race.

Finito…

[…] 1966 was the year of absolute F2 dominance by the works Brabham Hondas raced by Brabham and Hulme. Sad story on Schlesser, more positively, I am in the process of assembling a feature on the man, will finish it soon; https://primotipo.com/2019/07/12/its-all-happening-3/ […]