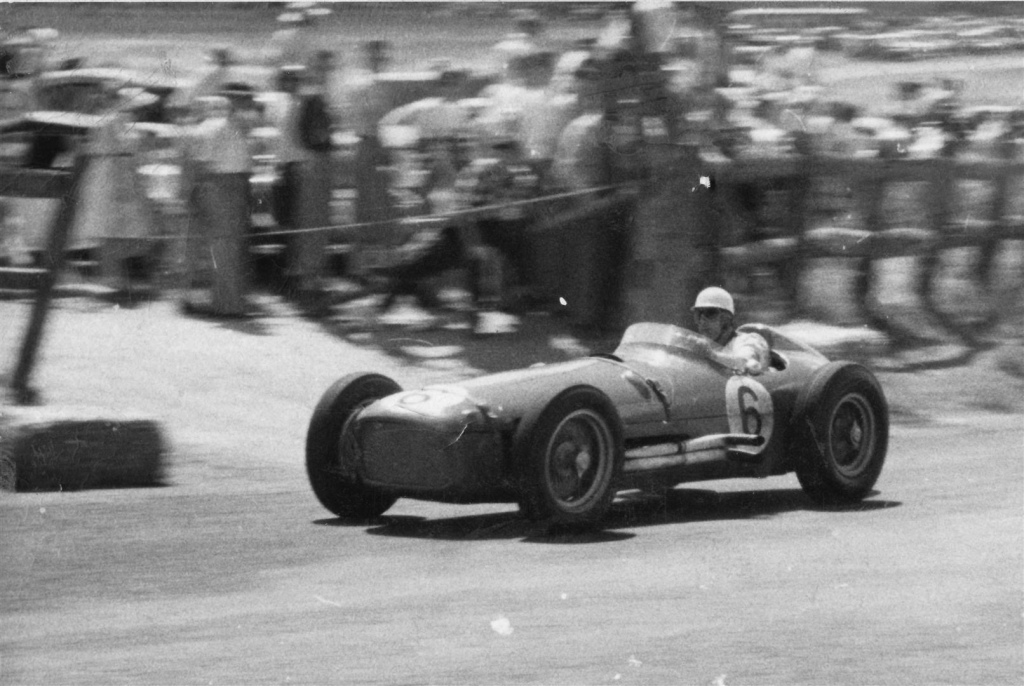

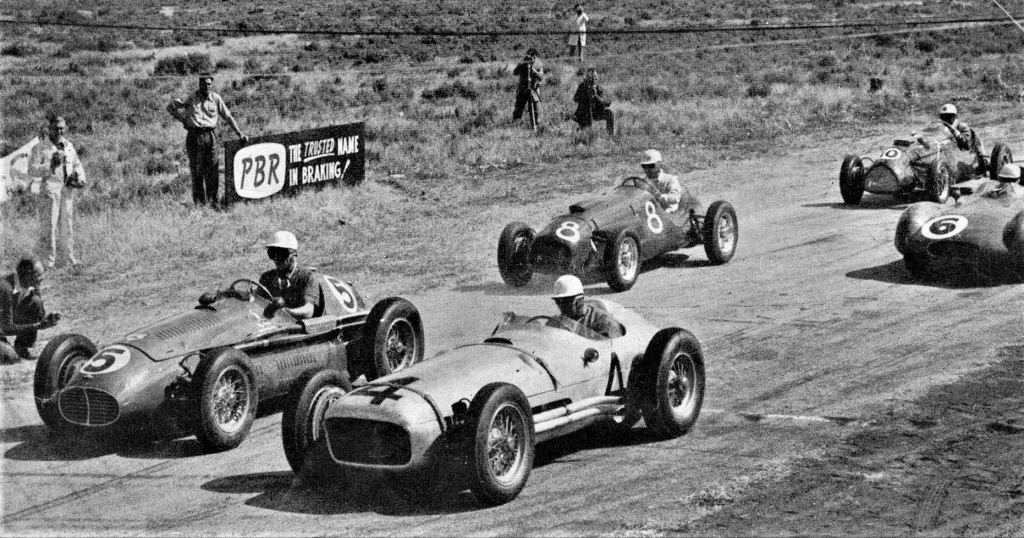

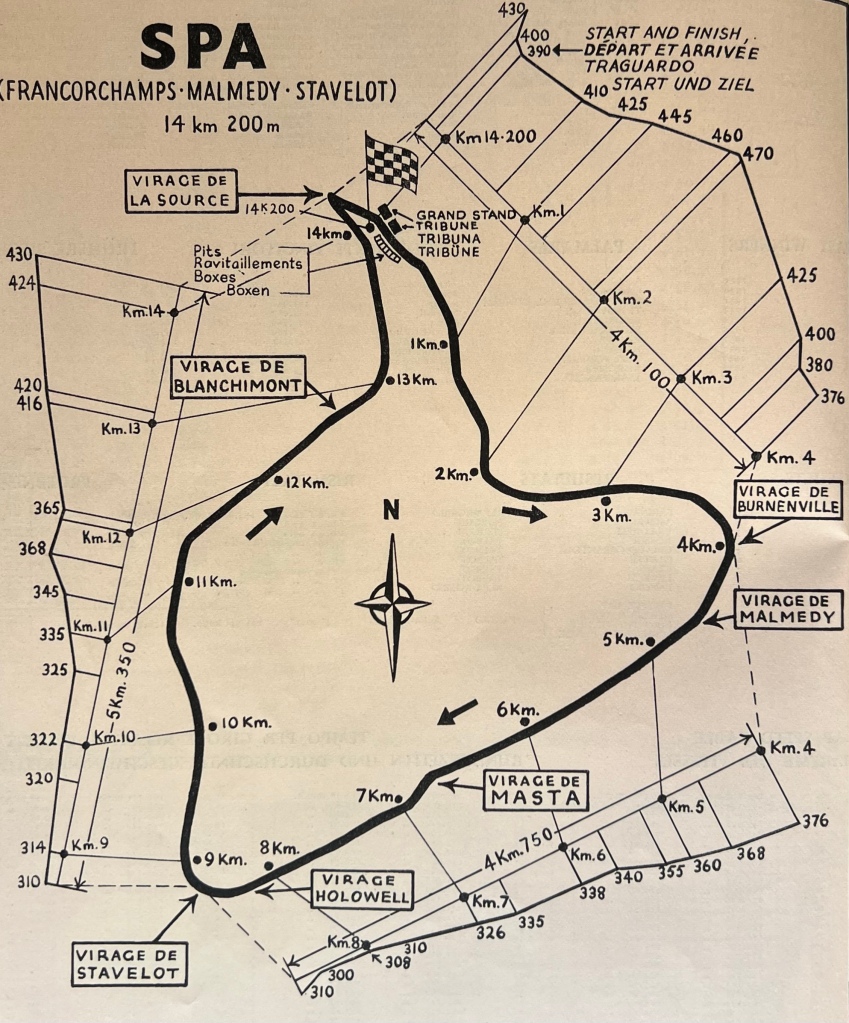

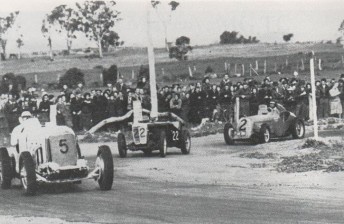

A thrilling race of course, Bruce McLaren took an historic win – as the youngest ever F1 championship GP winner, a title he held for yonks – after Jack Brabham’s Cooper T51 Climax ran out of juice on the last lap. Jack was fourth, Maurice Trintignant, Cooper T51 Climax was second and Tony Brooks, Ferrari Dino 246 was third.

The Americans entered F1 etc – Indy being part of the F1 World Championship from 1950-1960 duly noted – but the interesting thing was the mix of cars. Not just Rodger Ward’s utterly nuts and utterly wonderful, Kurtis Kraft Offy, but also Fritz d’Orey’s Tec-Mec F415 Maserati, Allesandro de Tomaso’s Cooper T43 OSCA Streamliner and Bob Said’s Connaught C-Type Alta.

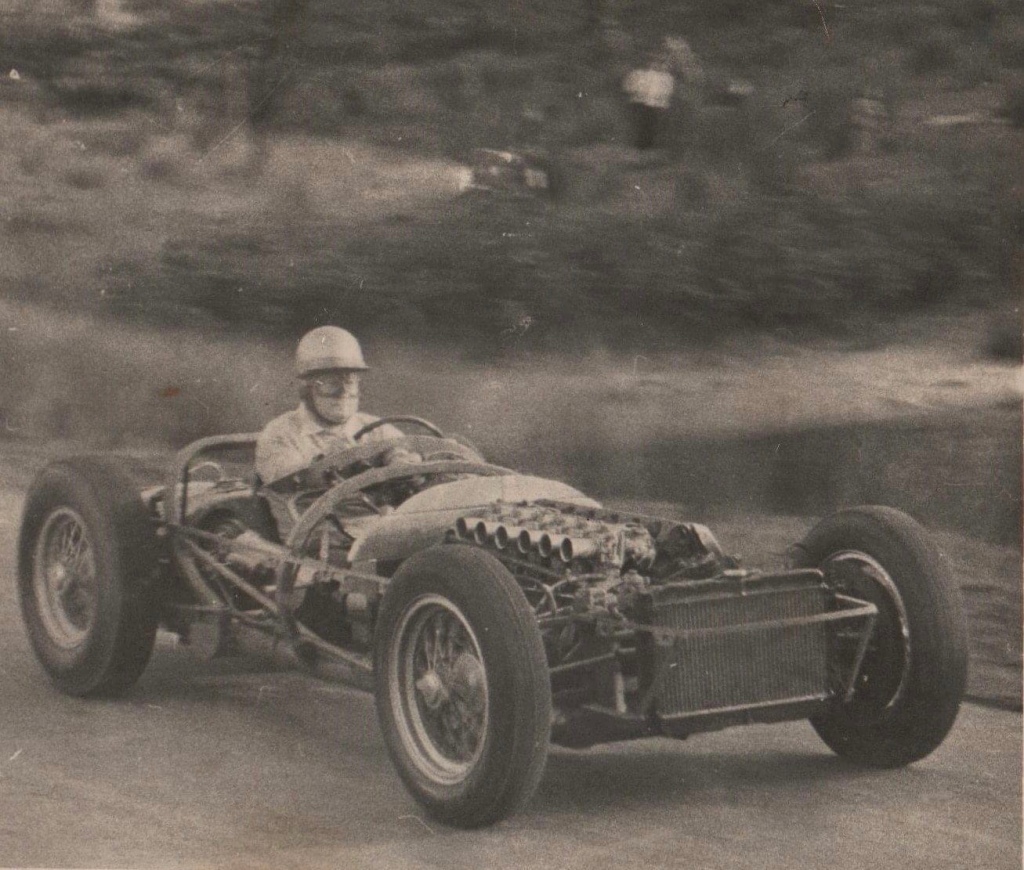

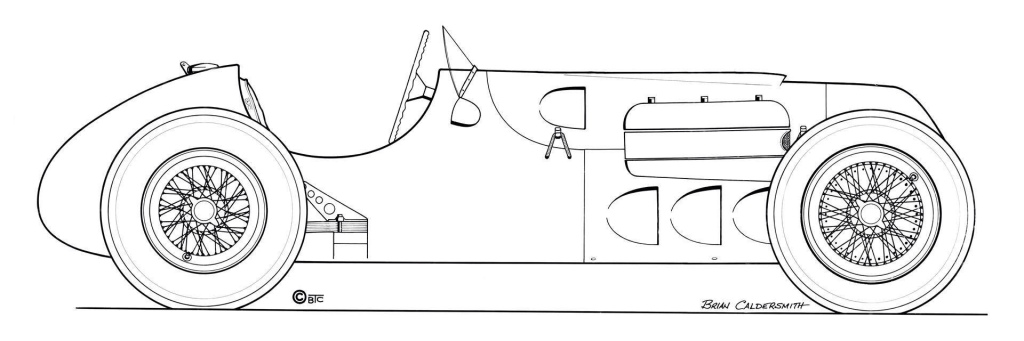

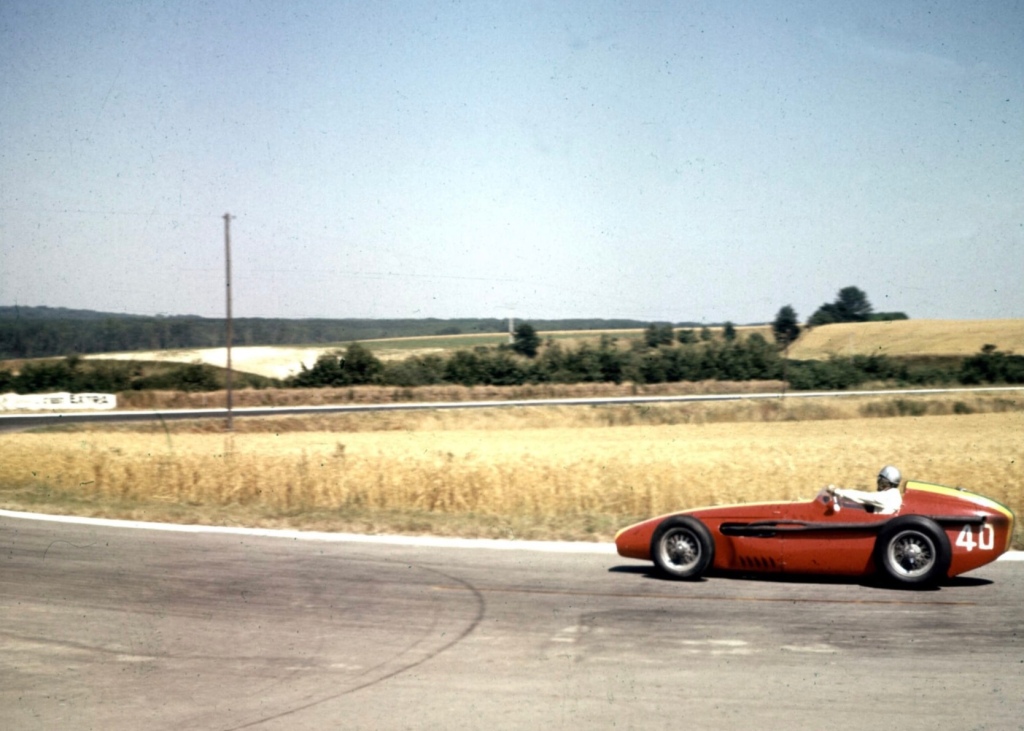

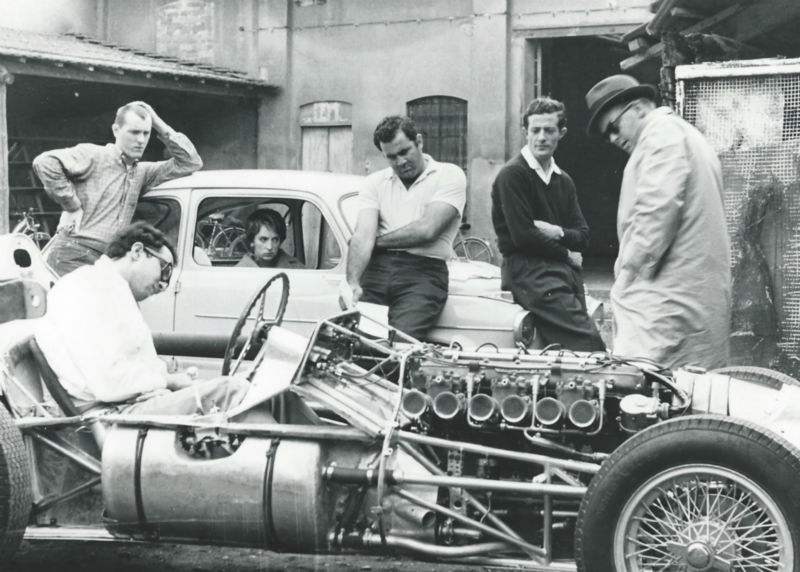

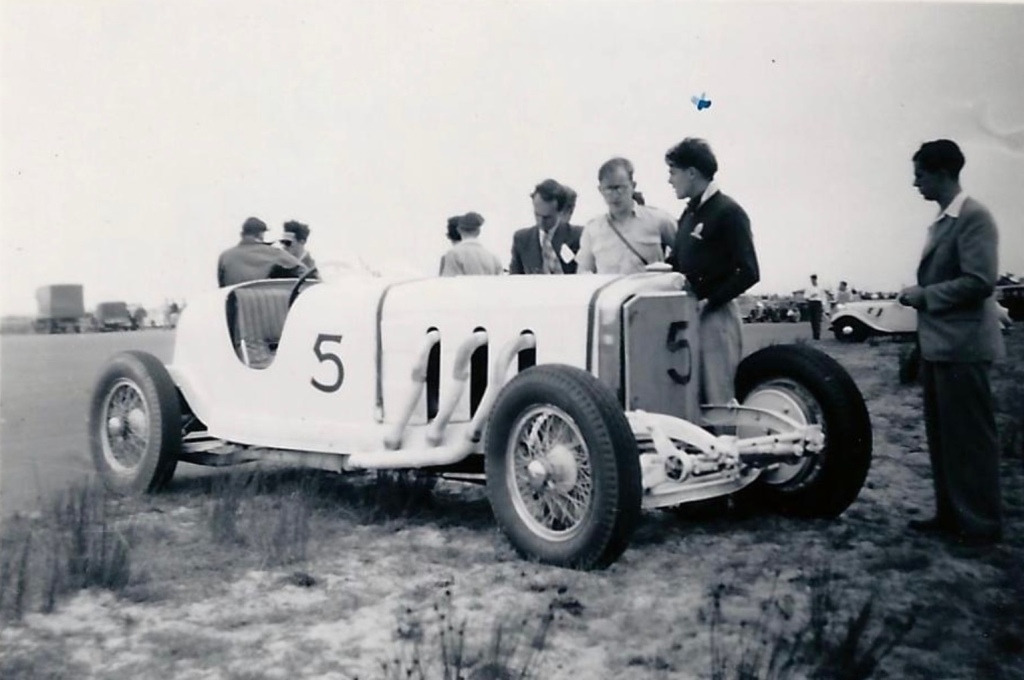

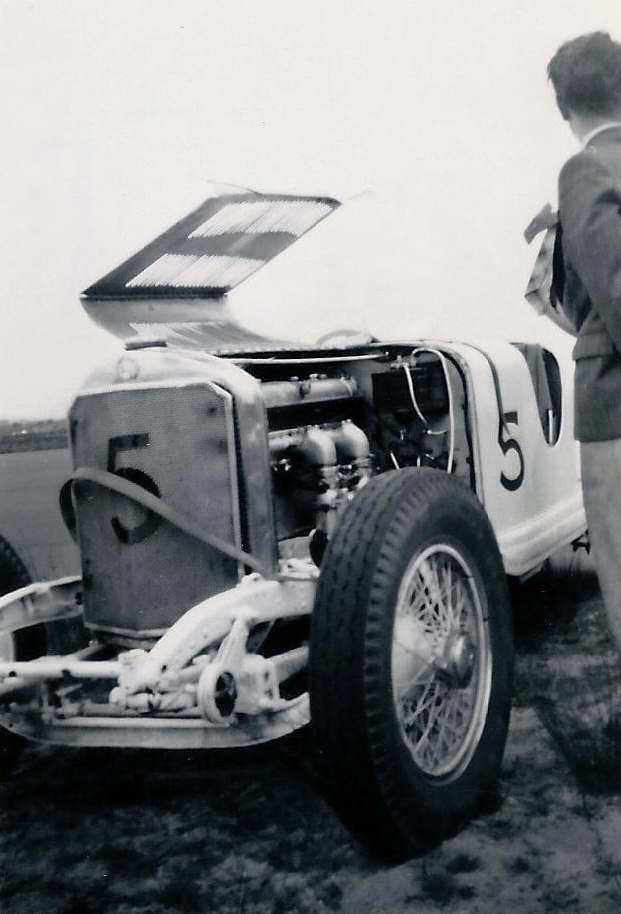

Fritz d’Orey in the one-off Valerio Colotti designed, Gordon Pennington owned Tec-Mec F415 Maserati at Sebring during practice.

Remember those days before carefully homogenised and pasteurised, hermetically clean and certified absolute sameness and dull-shit-boredom. Where did it all go wrong? See here for a story on this car: https://primotipo.com/2024/03/11/tec-mec-f415-maserati/

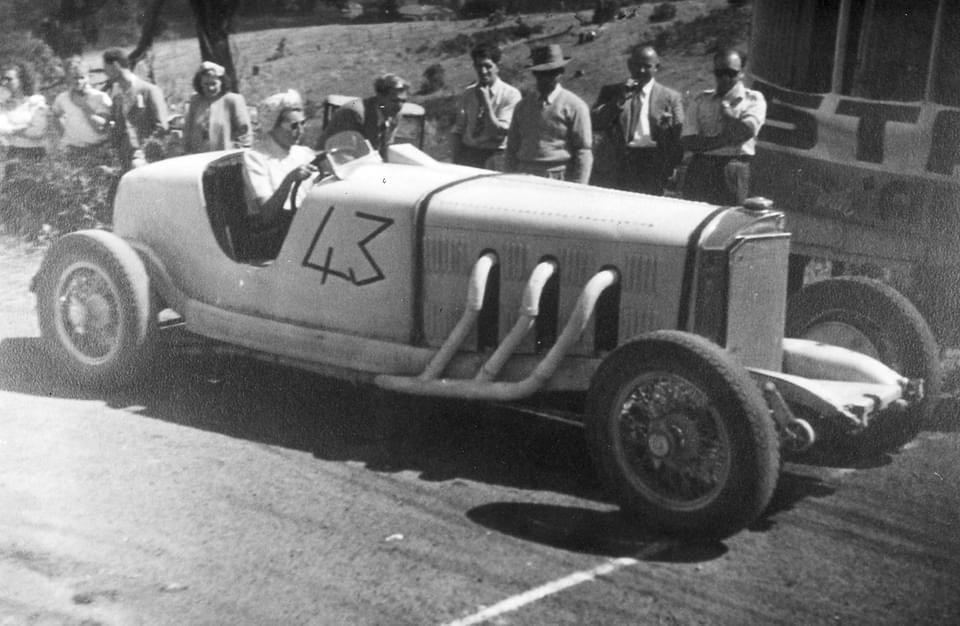

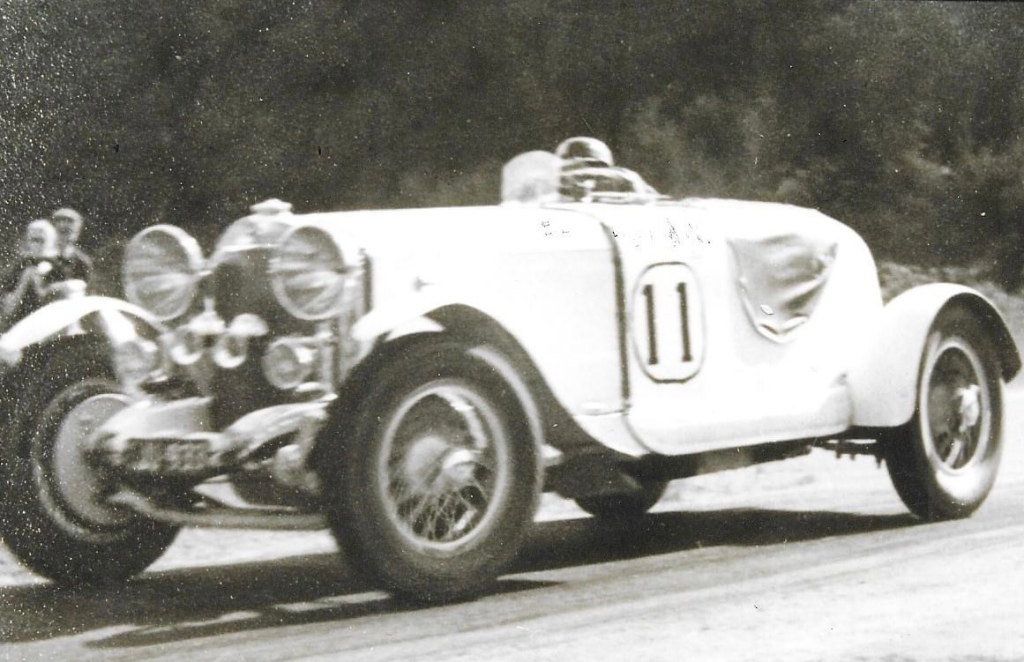

De Tomaso’s works Officine Specializate Costruzione Automobili entered Cooper T43 OSCA 2-litre was only ever going to be an also-ran given the modest displacement and endurance background its twin-cam, Weber fed four-cylinder engine. He qualified the car 14th on the 19 car grid and completed 14 laps before brake troubles intervened.

The car’s swoopy, beautifully finished and fitting body is far more attractive than any of the Coopers of that era, and more aerodynamically efficient? While said to be a Cooper T43, the chassis may be a copy, the wheels are also of De Tomaso’s design and manufacture. An interesting experiment, what became of the car?

It made great commercial sense for the organisers to run the reigning Indy 500 champion, Rodger Ward, in the race. If you believe the hype, Ward thought his lightly modified Kuris Kraft Midget would give the ‘European Buggies’ a run for their money.

Jack Brabham related to Doug Nye, “The next day he, Bruce, and and I arrived together at the first corner of the track, and just as we jumped from brake to throttle pedal and streaked away from him he was astonished. To his credit he took it well.”

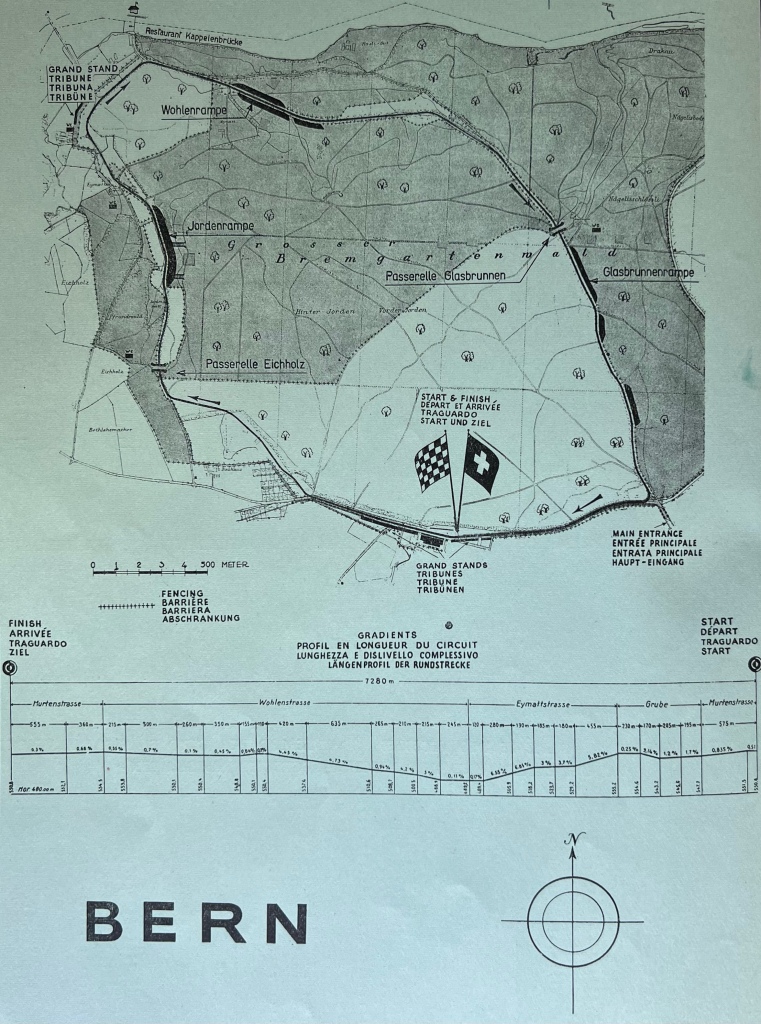

Ward’s qualifying time was well short of pole-sitter Stirling Moss in Rob Walker’s Cooper T51 Climax: 3 min dead vs 3 min 43.8 sec. Rodger lasted for 21 of the race’s 42 5.2-mile laps, getting as high as ninth as others retired, before clutch failure intervened.

A popular racer and a good sport, he became a Cooper convert overnight and worked on Jack and John Cooper to convince them to run a car at Indianapolis. After the 1960 US GP Jack ran his GP Cooper T53 Climax at Indy in a series of tests, aided and abetted by Ward; Coopers participation in the 1961 500 with a Climax powered Cooper T54 changed Indy history, and Rodger Ward played a key role.

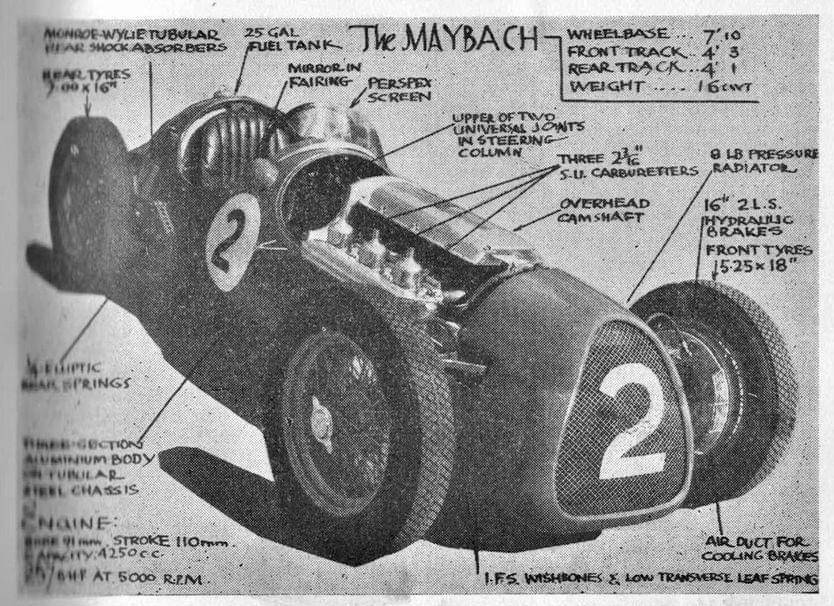

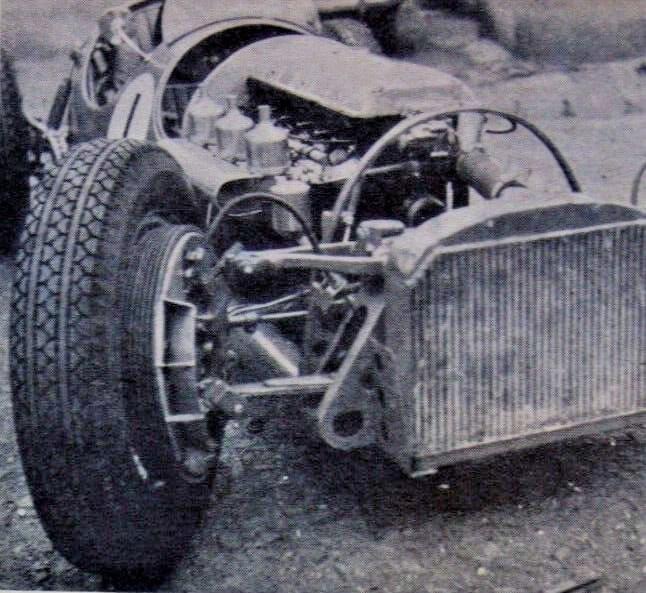

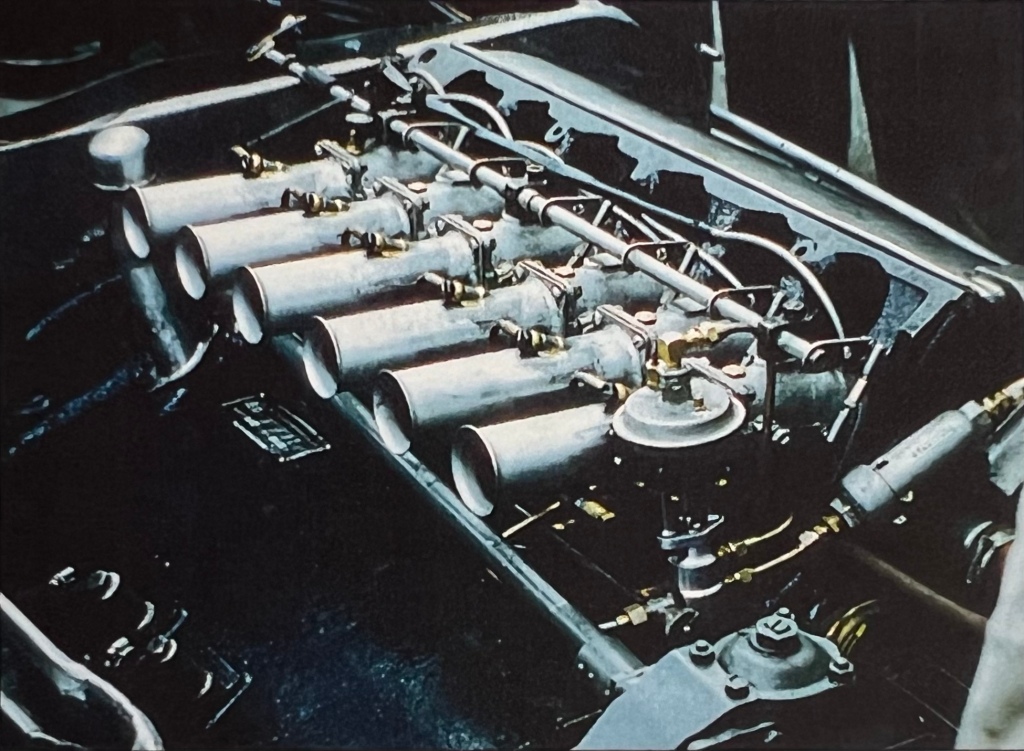

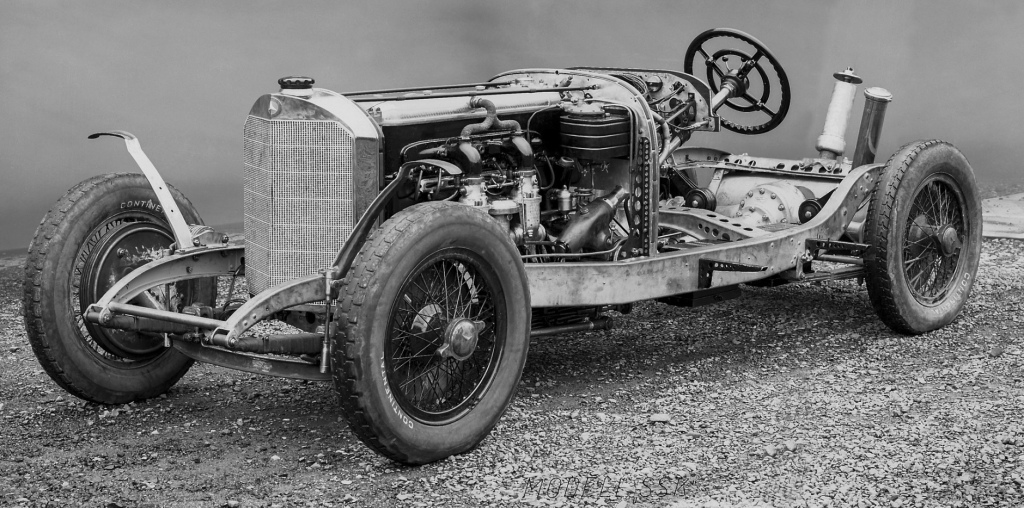

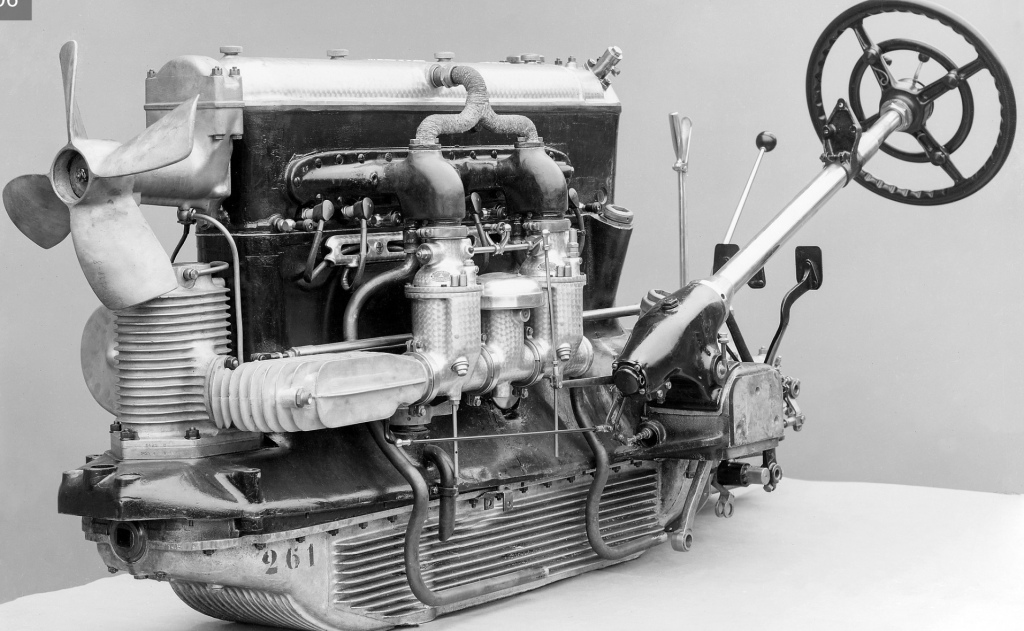

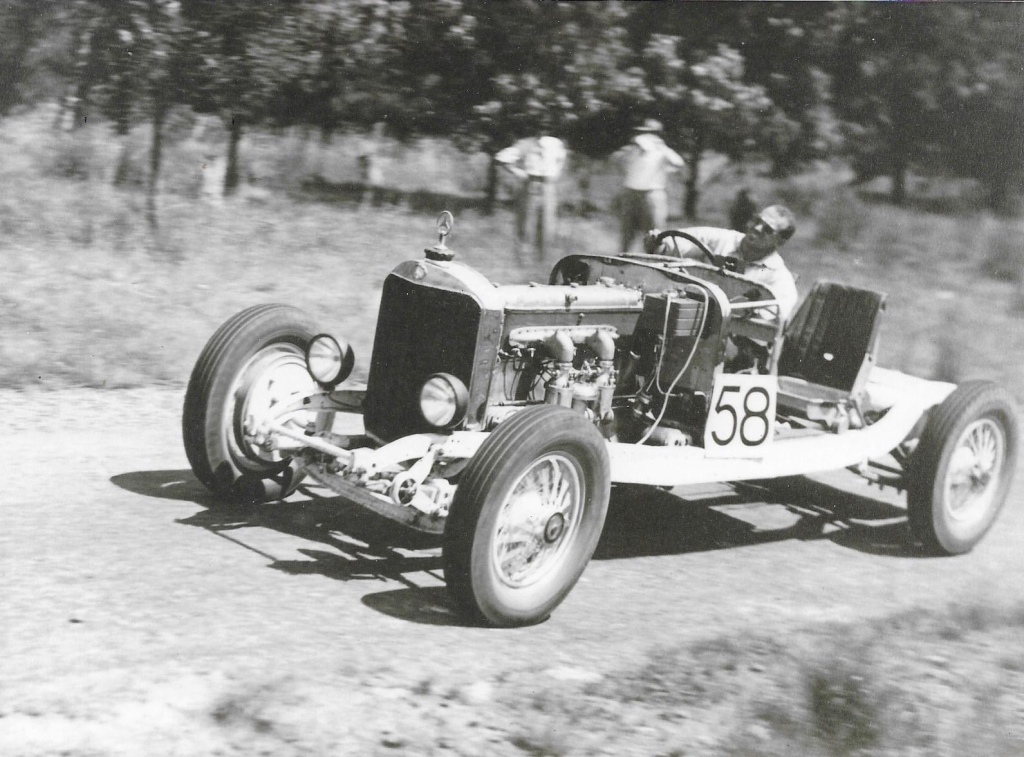

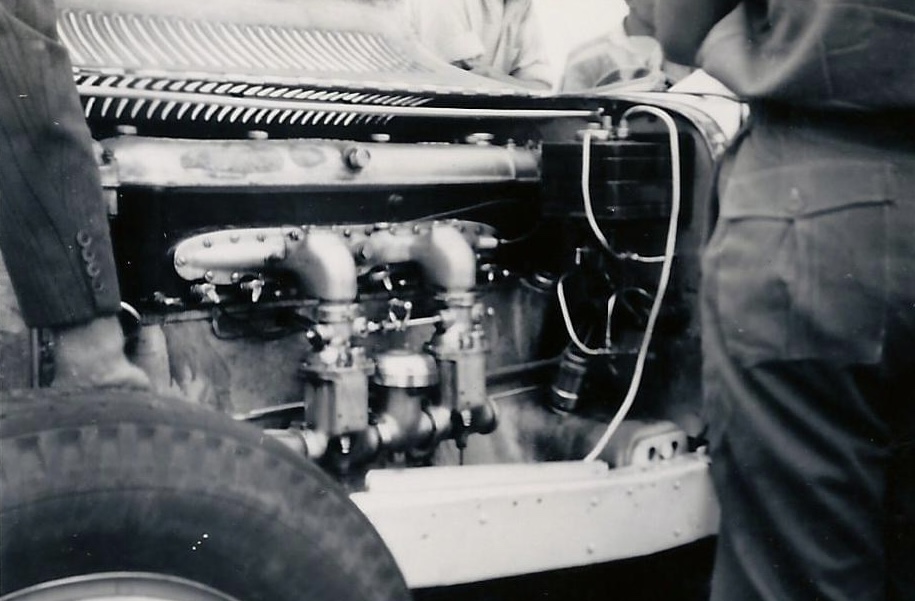

Ward’s 1946 Leader Card Kurtis Kraft Midget, chassis #0-10-46 was powered by a 1.7-litre, DOHC, two-valve Offenhauser engine that gave away heaps of performance to the mainly 2.5-litre competition. It had a two-speed gearbox, a two-ratio rear axle, hand-disc-brakes and the usual other dirt-track accoutrements! Those Halibrand wheels are 12-inches in diameter and Firestone provided the tyres.

The beam front axle is sprung by a transverse leaf and located bt two radius rods. I’ll take your advice on shock-absorbers. Note the front discs, nerf protection in front of the rear wheels and high standard of preparation and presentation.

Jesse Alexander observed the following about the Kurtis Kraft in his Sports Cars Illustrated meeting report.

“The greater part of the two practice sessions was spent getting the car to run properly on Avgas (rather than the usual methanol). The several times that it did appear on the circuit it was obvious that the few modifications to the chassis to suit it better for road racing were worthwhile. Surprisingly stabile and getting through many of the corners as fast (in some cases faster) as much of the field.”

“The red and white Offy differed from normal midgets in having its engine fitted several inches farther forward in the chassis as well as having a supplementary 2-speed transmission installed. This meant that actually there were two 2-speed units, one behind the engine and the other in unit with the final drive gears. But these alterations could never possibly make up for the displacement gap between the parky Midget and her overseas competitors.”

“Rodger Ward deserves credit for his spirit and enthusiasm – it was great to see him at Sebring and lets hope it won’t be the last time out for an Offy-engined car.”

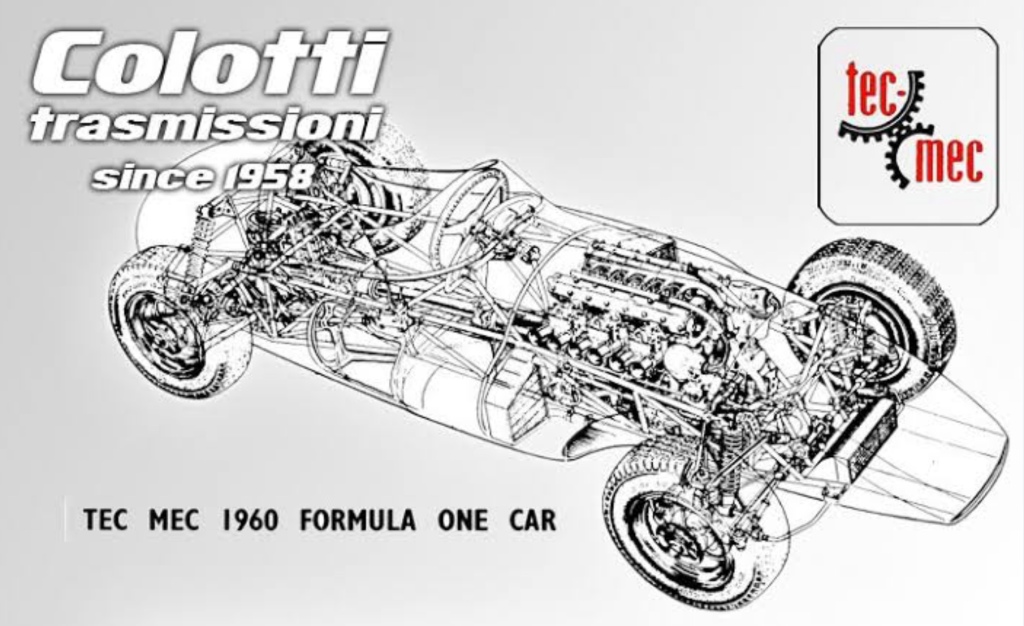

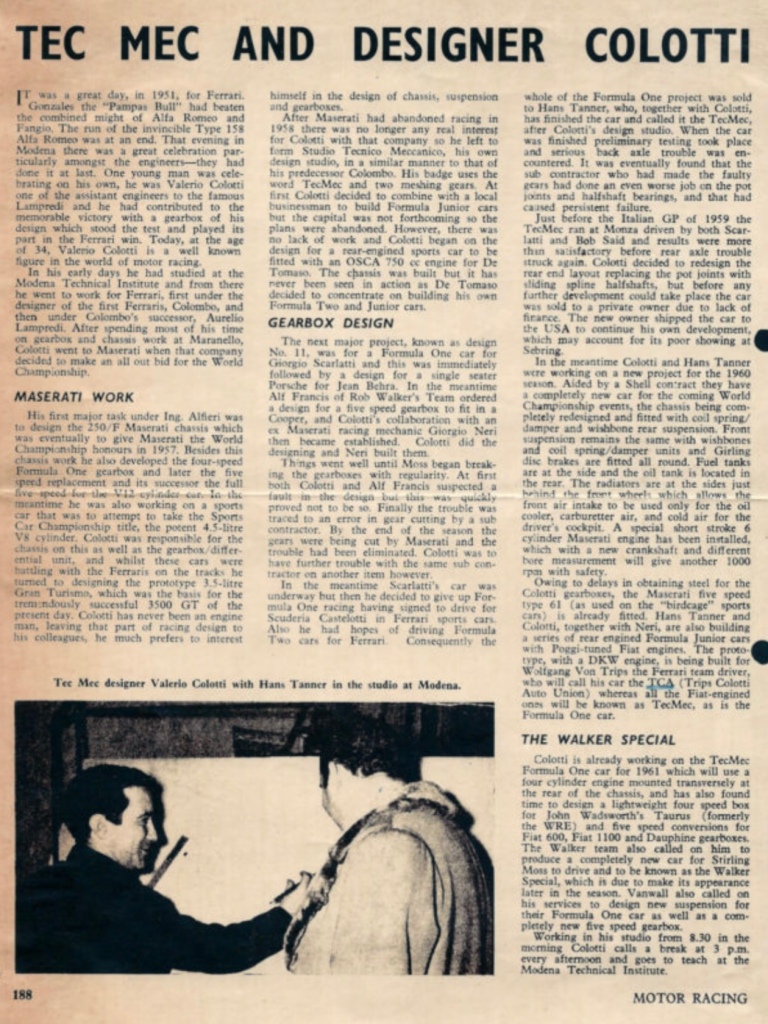

I wrote about the Valerio Colotti designed Giuseppe Console built Tec-Mec F415 Maserati – ‘the ultimate expression of the Maserati 250F’ – a while back, see here: https://primotipo.com/2024/03/11/tec-mec-f415-maserati/comment-page-1/

By late 1959 the car was owned by Florida man Gordon Pennington, he decided to enter the machine for its one-and-only race at Sebring.

With Brazilian wealthy-journeyman Fritz d’Oley at the wheel, the new car, being run for Pennington and D’Oley by the Camoradi Team, managed to qualify 16th, one grid-slot in front of the only 250F in the race driven by Phil Cade.

The Tec-Mec completed 7 laps before an oil leak forced Fritz’ withdrawal, while Cade didn’t take the start given the old-gal’s lack of pace: 3 min 39 sec in qualifying. While Tony Brooks’ front-engined Ferrari Dino 246 was third, and the Dinos raced on into 1960, Ferrari wheeled out a mid-engined prototype at Monaco that year.

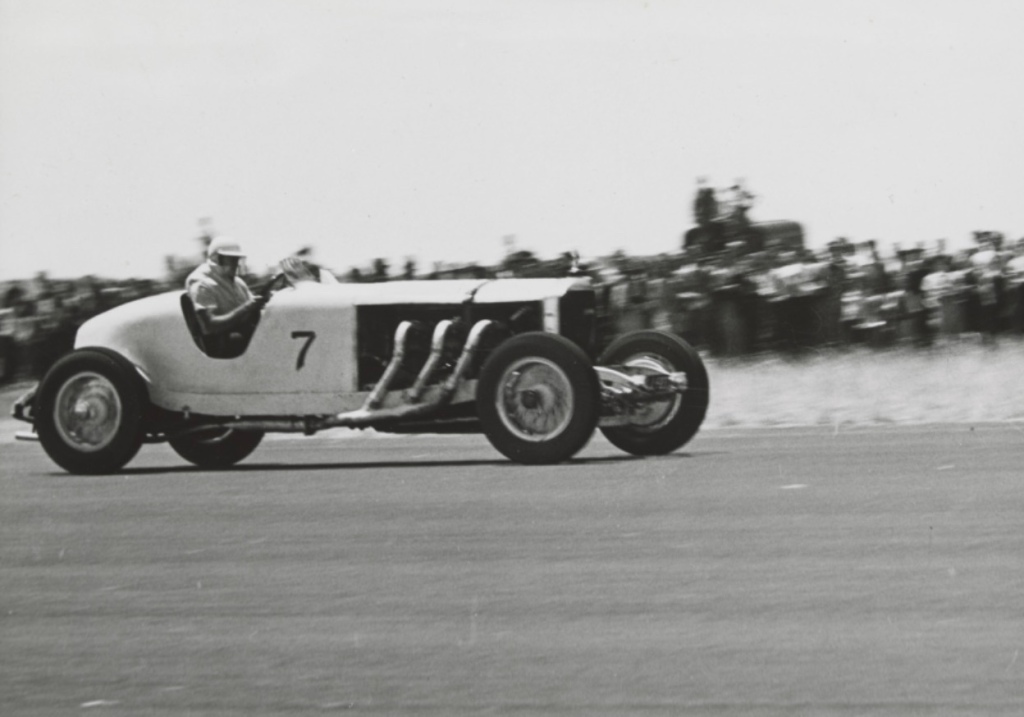

Fritz d’Orey, Tec-Mec F415 Maserati during the race. “The Tec-Mec was never driven quickly enough to show up any defects. The only time we know of it being driven fast was when Jo Bonnier took it around the Modena Autodromo last summer. His comments were not all that favourable. He complained of, among other things, a flexing chassis.”

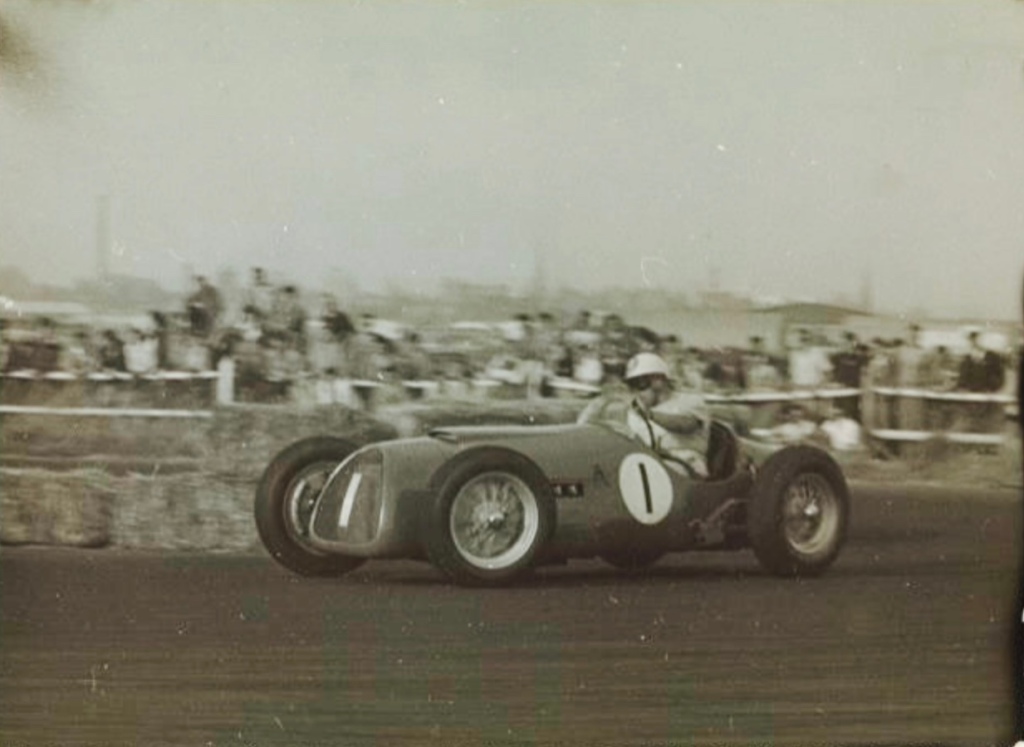

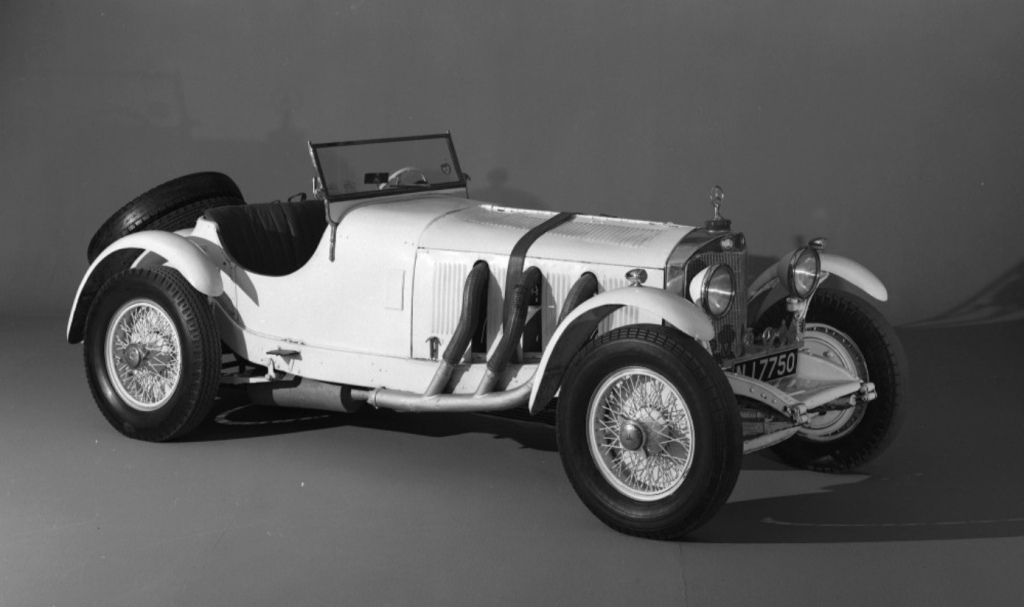

A bit like the Tec Mec, the Connaught C-Type Alta (chassis #C8) was also stillborn.

Rodney Clarke’s spaceframe chassis, disc braked, strut/De Dion tube rear suspension, double wishbone front suspension, Alta DOHC, two-valve four powered, Wilson pre-selector ‘transmissioned’ vast improvement of Connaught’s successful B-Type was tested but unraced when the assets of Connaught Engineering were sold in 1957.

Passed in at the auction, #C8 was later sold to Paul Emery (of Emeryson fame) and “keen amateur racing driver John Turner”. They soon did a deal with American driver, Bob Said, to race the car at Sebring.

Inevitably, shipping delays meant the project was knee-capped from the start. Poor Said had little testing time, with fuel injection difficulties adding to the challenge. He qualified the car a great 13th in the circumstances but had clutch problems in the race and then crashed it when he was caught out by the Alta engine’s erratic throttle response without completing a lap.

Jesse Alexander wrote, “The Connaught with Bob said driving drew many interested onlookers. This was the first racing appearance of the space-framed car that was under construction back when Connaught decided to cease building and racing cars. They never sold this one, which embodies many novel design features like a telescoping de Dion tube and servo-operated Lockheed disc brakes. Paul Emery got it running well enough for Said to turn a 3:27.3sec practice lap.”

While outside the scope of this article, the car was repaired back at the Send factory, near Guildford. With six inches added to the wheelbase, cut-down bodywork, a push-bar, and the Alta fuel injected engine tuned to 260bhp on methanol, Jack Fairman attempted unsuccessfully to qualify the car for the 1962 Indianapolis 500.

It’s such a shame this Connaught didn’t contest Grands Prix in 1957 as planned…

C8 was sold via a Road & Track ad and then lived in a private California museum from late ’62 until 1974 when Rodney Clarke repatriated the car to the UK. In another Tec Mec similarity, the car has been an historic racing front runner for decades, initially in Indy LWB spec and since the late 1990s in its original GP specifications.

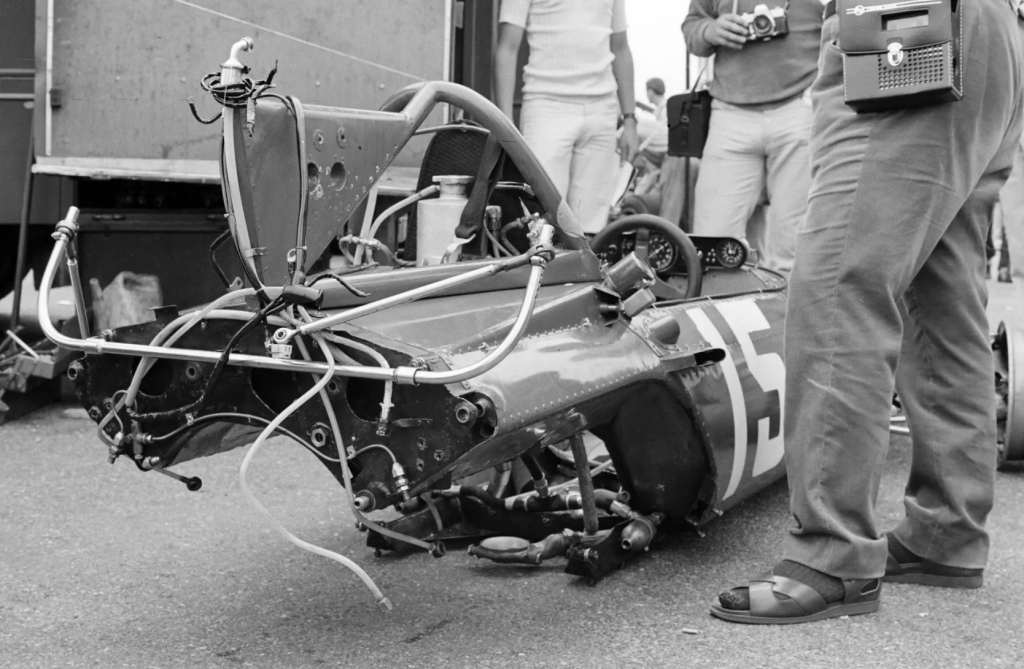

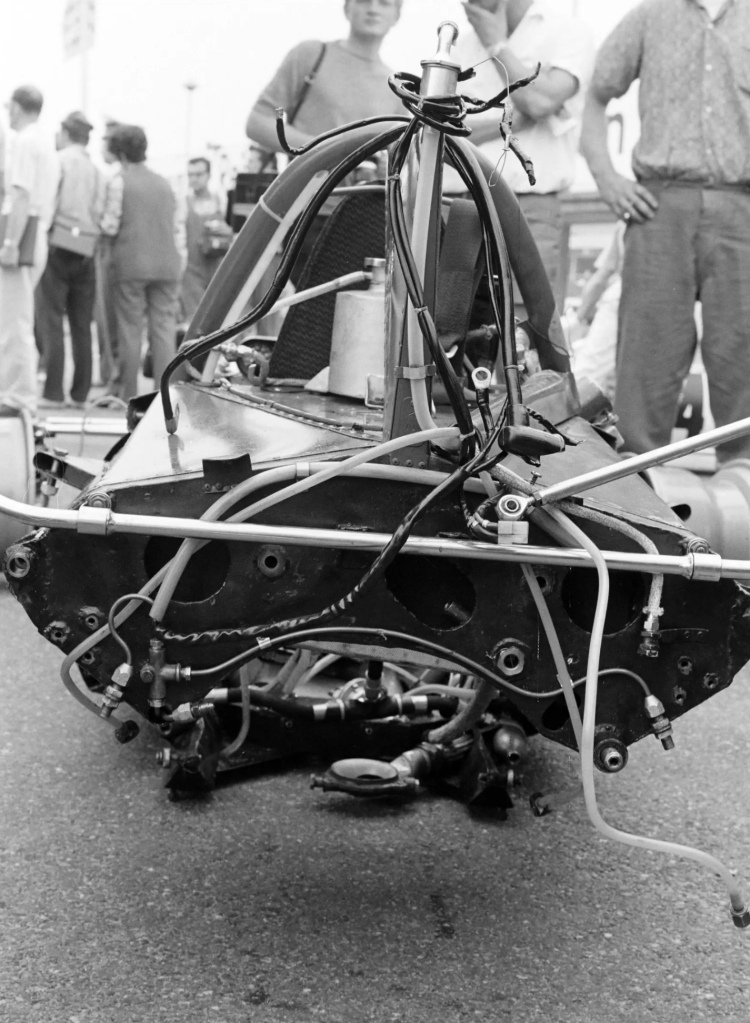

Stirling Moss’ Rob Walker Cooper started from pole but was out after only five laps with Colotti gearbox failure.

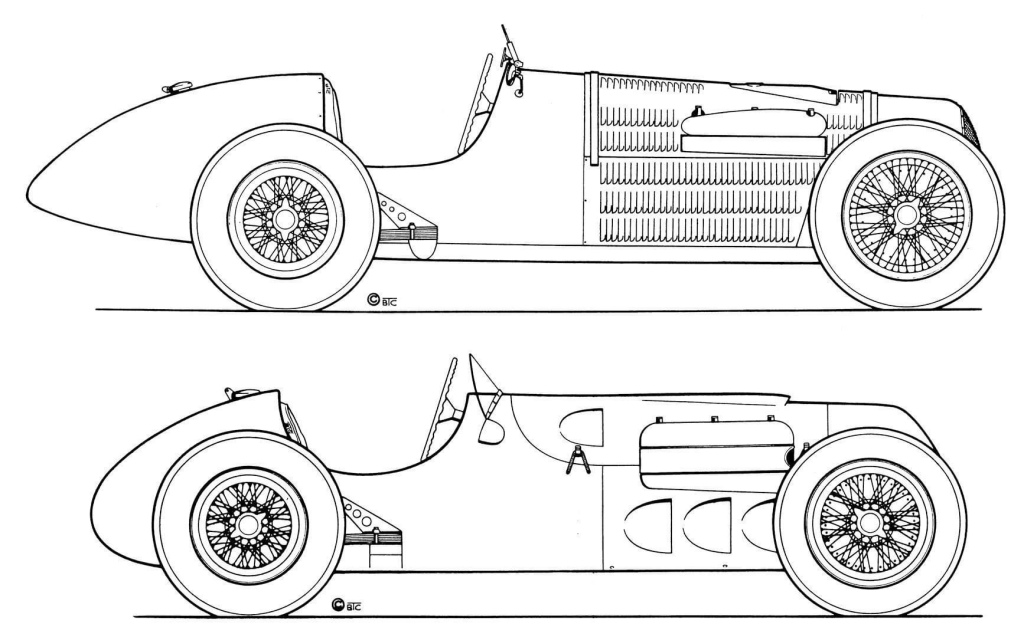

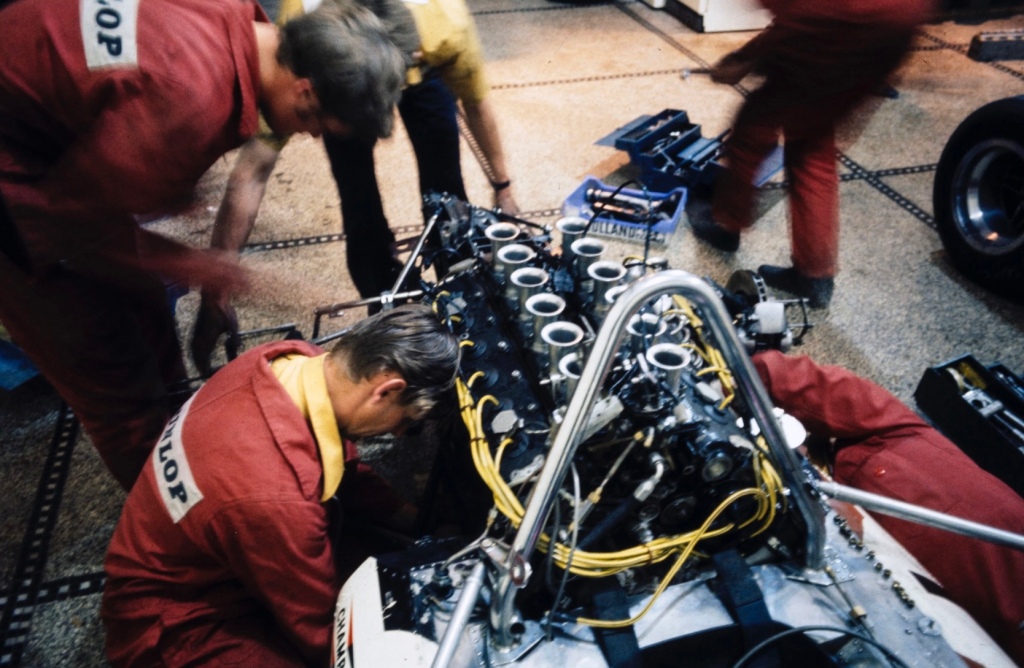

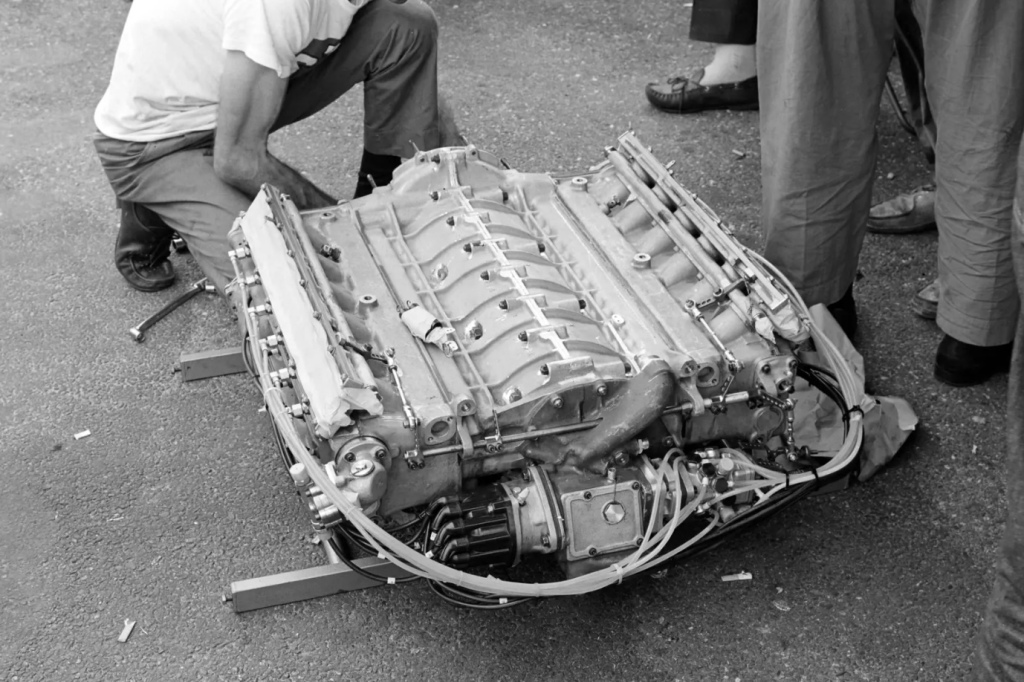

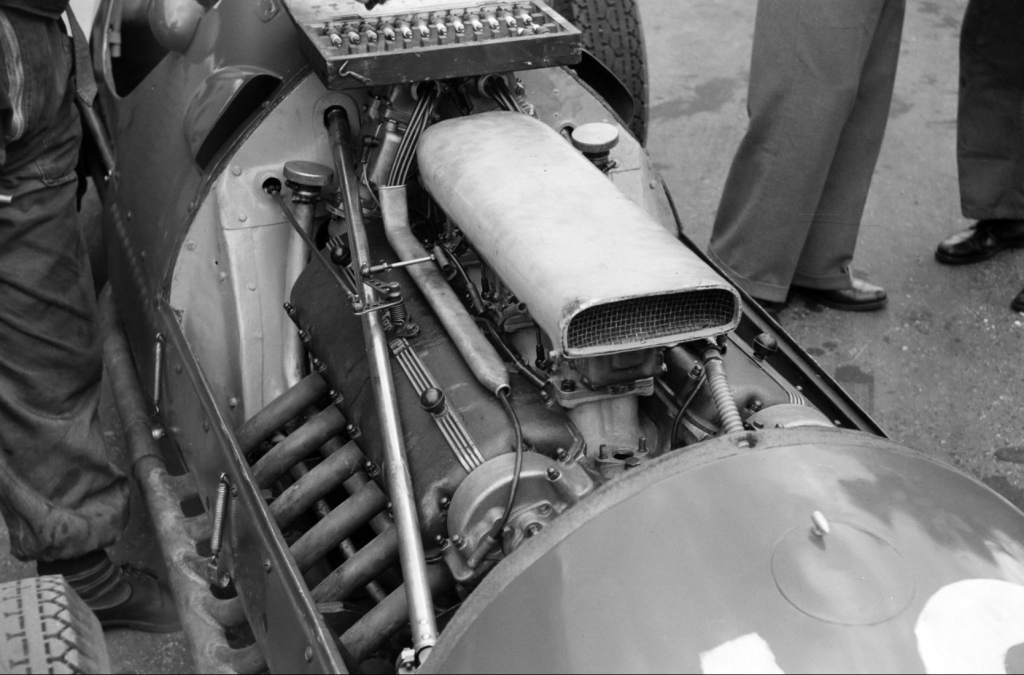

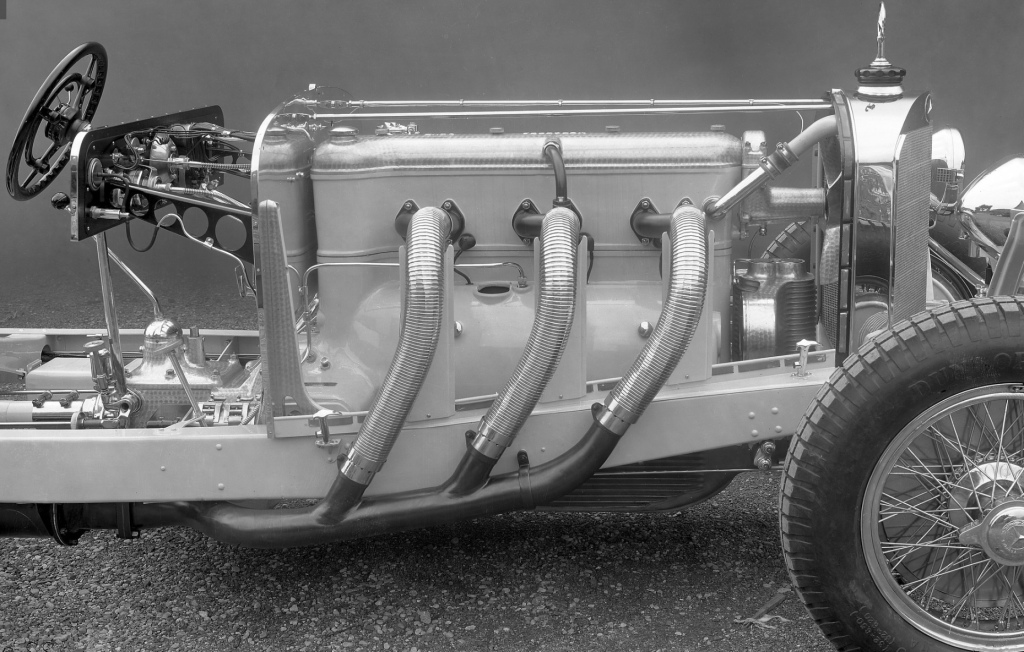

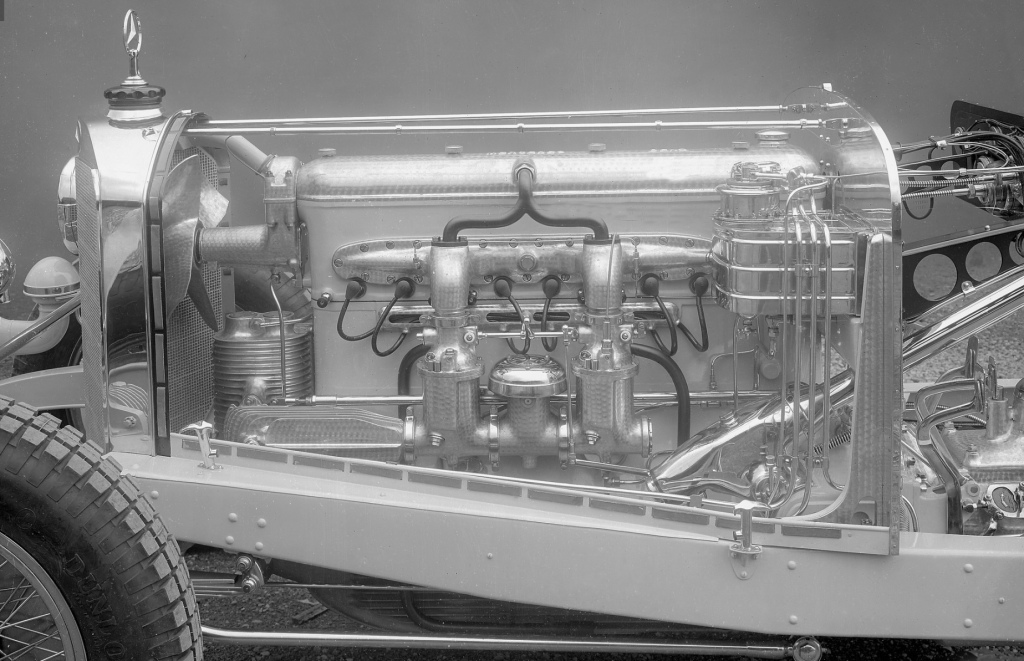

Alf Francis had modified the rear suspension from the standard Cooper transverse leaf setup to coil springs and ‘wishbones’ as shown in the shot below.

Jesse Alexander explains, “The new rear suspension had been tried out in the Fall back in England. Stirling liked its feel, then proved it by bettering the Goodwood lap record. Wire wheels at the rear, and the Colotti five-speed transmission were the only major differences bwtween the Walker cars and the works cars of Brabham and McLaren.”

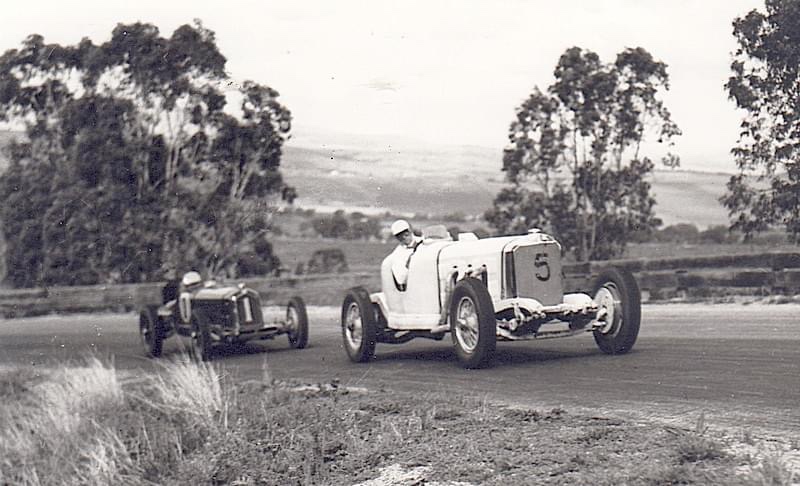

Bruce McLaren – with Jack in front of him – demonstrates the geometry of the standard T51 transverse leaf layout (at Sebring) where said spring performs that task, and locational duties. The 1960 Cooper Lowline (T53) quickly concocted by Messrs Cooper C, Brabham, McLaren and Maddock after the first race of the year, included among its successful bag-of-tricks a coil sprung rear end.

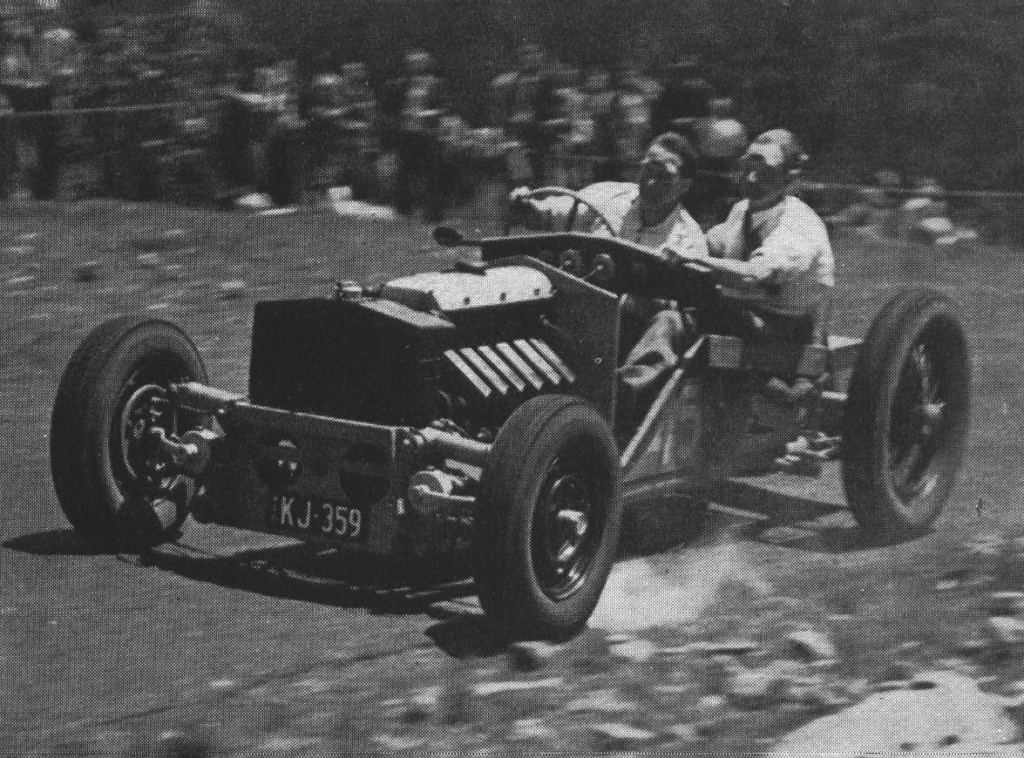

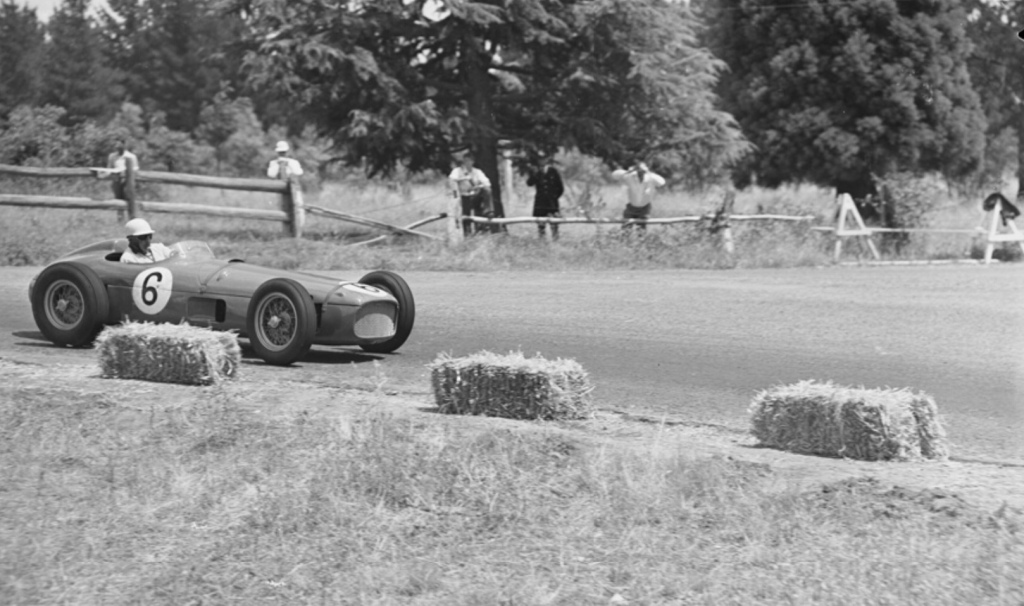

McLaren enroute to victory above. Alexander tells us that Brabham had initially practiced this car but “it had experimental settings for 1960” and Jack didn’t like the feel of it, so he and Bruce swapped chassis. “McLaren had not even expected to race at Sebring when I spoke with him in England in October. He expected to be in New Zealand for Christmas and participate in their Grand Prix. As it turned out, Masten Gregory’s injuries failed to heal in time for him to race at Sebring and Bruce replaced him.”

Didn’t fate play a couple of hands in Bruce’s favour!

Credits…

MotorSport Images, Jesse Alexander in Sports Cars Illustrated March 1960 via Stephen Dalton’s archive, William I’Anson Ltd

Tailpiece…

Just luvvit…

Finito…