164 MPH IN A VINTAGE BENTLEY–THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JOHN LEMUEL ‘JUMBO’ GODDARD – A GENTLEMAN ADVENTURER

“Jumbo liked shiny things”.

A legend in his own lifetime, much has been written about John L. Goddard. His life story has been told by journalist luminaries including Bill Boddy (Motor Sport, 12/62), Pedr Davis, (Sports Car World, 9/63), John Croxson (Autocar, 1/73), Eoin Young (Classic Car, 8/74) and Doug Nye (Collector’s Cars, 11/79). There was also an excellent review of his life written by Tom King in the New Zealand Rolls Royce and Bentley Club magazine in 2012. Mark Bisset thought it was time to introduce Jumbo to a new audience.

It’s said that John Goddard acquired his nick-name – by which he was always addressed – when his generous size was observed by Captain J.E.P. Howey who remarked “Hmmm…he much resembles a pantomime elephant from behind, doesn’t he”? Jumbo was very much in the ‘Bulldog Drummond’ mould of “a class of Englishman who were patriotic, loyal and ‘physically and morally intrepid’”. Far be it for the writer to question Jumbo’s morals, but the description otherwise fits perfectly. Jumbo’s lifestyle was not for the ordinary mortal; it required not only that ‘Englishness’, but also the means to indulge his passions.

Early days

Born at the inappropriately named Tilbury Forest Cottage (more of a mansion than a cottage), at Peas Pottage, Jumbo was brought up in comfortable circumstances. His Barrister father Jack was a sporting motorist who favoured big Daimlers – for a time he held the hill record at South Harting driving one of these chain-driven monsters. His six cars were maintained in a fully equipped, tiled and centrally heated workshop by a staff of four, chauffer, second chauffer, mechanic and washer. The machine tools were driven by an electric motor powered by a Ruston engine and generator set. These were accommodated in a sunken power-house accessed by polished hand rails and white-washed steps. Electricity was also available to light the house, pump water and power an organ – unlike the workshop, the house was not centrally heated. At an early age Jumbo stood on a box to watch the operation of the workshop machinery – it seemed his fate was sealed. Rather than follow his father into the legal profession, he opted for a mechanical engineering apprenticeship with J.G. Parry Thomas at Brooklands Motor Course, but this was not to be when Thomas died during a world-speed record attempt in his 27-litre chain-driven ‘Babs’ in March 1927.

While still a school-boy, Jumbo obtained a three-wheeler Morgan which was followed by a Francis Beart tuned Morgan Blackburne which had a formidable power-to-weight ratio – 5 cwt. and 60 to 70 bhp on a good day – the rear tyre had a short life. With this notoriously difficult device he obtained a Brooklands Gold Medal by lapping at over 100 mph. After a brief flirtation with two wheels (frowned on by his parents) he moved to a “gutless wonder” MG 14/40 which was quickly replaced by a 2-litre, 6-cylinder Marlborough which again did not meet with the owner’s approval. His next move was pivotal in his motoring career; he replaced the “fantastically awful” Marlborough with a Red Label 3-litre Bentley.

In a pattern that was to become familiar, Jumbo was soon improving the car; replacing its single Smiths carburetter with twin SU’s. By now a 19-year-old marine apprentice with John I. Thornycroft’s Woolston shipyard, he went a step further, supercharging the Bentley engine with a Cozette supercharger attached to a redesigned cambox cast in bronze by Thornycrofts to his design. As this did not provide sufficient urge, the next step was to replace the 3-litre engine with one from a 6 ½ litre car, enlarged to 7.2 litre’ and developing 175 bhp. On completion of his Thorneycroft contract, he set up a boatyard at Hythe on Southampton Water which was short-lived.

His considerable passions were not confined to the motorcar as he also had a love for boats and steam. There are no photos of a young Jumbo sailing a model boat on some idyllic pond in rural England, but by the late twenties he had owned a speed record holding steam driven boat, Miss Chatterbox IV. She was replaced by a slipper stern-drive boat ‘Shawk’ which had previously been owned by Count Louis Zborowski. Jumbo’s ‘improvement’ was to replace the previous engine with a Zeppelin from a plane that had been shot down over England. Steam interests were maintained by working as a train driver on his friend Johnny Howey’s Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway.

Jumbo made his first visit to Australia in 1934, but no first-class cabin for him; he worked his way before the mast on one of the most famous grain ships – the 4-masted barque Herzogin Cecilie (below) which won the Great Australian Grain Race eight times in succession. (This would have been no pleasure cruise – for an account of the hardships experienced on one of these grain boats, Eric Newby’s ‘The Last Grain Race’ is recommended reading). He then had a period sailing the South Pacific on a trading schooner while enjoying the associated delights.

He liked what he saw in Australia and purchased a Ford V8 ute which he drove from Brisbane to Perth. He became interested in prospecting for minerals, spending the pre-war years in New Guinea where he also worked as a fitter and turner in a mining venture.

Just before the war he was back in England, buying a blower-4½ litre Bentley described as a bundle of trouble coupled with an 8-mpg thirst. During the war he was attached to the Admiralty doing design work on propellers for 110-foot Fairmile motor torpedo boats powered by four Bristol Hercules engines – the idea of 56 cylinders and 18,000 hp would have appealed to him, and possibly gave him ideas for a record-breaking car in the future. (‘There is no substitute for litres’). He was one of the many brave volunteer seamen involved in the Dunkirk rescue using a flotilla of little boats.

A Fiat 500 and various Morris’s sufficed as wartime transport, but on the conclusion of hostilities he bought a 1½ litre Aston Martin which wanted “150 hp on account of its weight”. A more satisfactory solution was a 328 BMW which was followed by an ex-Peter Whitehead XK 120 Jaguar which he progressively modified with a C-type specification engine and disc brakes – he kept this car for the rest of his life.

In a derelict building he found a competition 9½ litre Cottin-Desgouttes which had taken the Mont Ventoux hill record in 1911. His 3-litre Bentley now had a 4½ litre motor. An 8-litre Bentley chassis which had been converted to an ambulance was purchased – this car will feature later in our story. To this burgeoning collection was added the ‘cherry on the top’, the two-year-old D-type Jaguar OKV 1 driven to second place at Le Mans by Hamilton and Rolt in 1954. This car, too, will be re-visited.

In 1957 Jumbo signed on as an ordinary seaman on ‘Mayflower II’ with Allan Villiers, sailing from Plymouth, Devon to Plymouth, Massachusetts in a 56-day voyage replicating the 1620 voyage of the original Mayflower.

His peripatetic lifestyle led him back to Australia in the late forties where he prospected for uranium. In Alice Springs he befriended pioneer aviator Eddie Connellan and took an interest in Connellan Airlines which operated in the Northern Territory. He then joined Consolidated African selection Trust, prospecting in Sierra Leone and Ghana. In the absence of female company, evenings were spent playing poker with uncut diamonds as chips.

After his retirement in 1962 he spent most of his time in Australia with his expanding car collection. The D-Type was brought here, to which he added a Type 35C 8-cylinder supercharged Bugatti that he had stumbled on in a local village. He had its counterpart in England, a Type 51 with similar specifications to the Type 35, but twin overhead camshaft. At one time he also had a Le Mans 4.9-litre Type 50 Bugatti and a Type 57.

Other cars, some of which shuttled back and forth between England and Australia, included three Frazer Nashs – the ex-AFP Fane single-seater which had broken the Shelsley Walsh hill record in 1937, a TT Replica and an Australian car modified into a single seat racing car. His English collection was cared for by his friend Tom Wheatcroft at his Donington Museum.

Jumbo settled at Newport Beach, overlooking Pittwater and his beloved Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club – the oldest yacht club in Australia. The term ‘idiosyncratic’ better describes Jumbo than ‘eccentric’. This extended to his habitual dress featuring sockless and lace-less desert boots, later replaced by similar plimsolls; his shorts had invisible mending over previous iterations of the same and were held up by binder-twine. His sockless state, however, did pose problems as he was unable to enter the main clubrooms of his yacht club, being confined to the downstairs public bar. His dress was completed by a Victorian Police issue blue shirt with epaulets.

He named his home at Pittwater ‘Hove To’, acknowledging that his international sailing days were over. It consisted of two houses joined by a covered and carpeted passageway crammed with ephemera pertaining to his motoring, nautical and steam interests. Whatever space was left was filled by his book collection – for reasons the writer never fathomed, Jumbo always had two of each book. To access the motor-house, which was at the top of a steep driveway, a car had to be driven onto a turn table which was then rotated towards the garage, or, if you were sufficiently skilled, you could land on the table with enough impetus to have the car pointing in the right direction.

Once in the garage you were exposed to his delightful and changing collection; at any one time there might be his Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing which had been converted to RHD, a supercharged MG TC, a minivan into which was shoe-horned a Lotus Ford twin-cam motor, a competition 904 Porsche alongside a four-cam roller bearing Carrera 356, the Bentleys and Jaguars as well as a 30/98 Vauxhall, previously owned by the writer, which had received the full Jumbo treatment with a special aluminium cylinder head designed for him by his friend Phil Irving, with pattern making and machining done in Bob Chamberlain’s workshop in Port Melbourne.

Awaiting his attention was a much-modified Vauxhall 30/98 chassis known as the ‘drain-pipe special’ in the light of its tubular chassis members, into which he intended to fit a WWI Hispano Suiza aero engine. In England he still had the 8-litre Bentley chassis which he saw as a suitable recipient for a 12.7-litre Bugatti Royale motor from a French motor-rail. All cars were modified – even his minivan had horizontally opening rear doors which provided a picnic table when open.

A weekend at Jumbo’s was a wonderful experience. One was greeted by Jumbo with his up-side down smile, once described as a contented scowl, informing one that a visit to the yacht club for a drink was confined to the public bar– “Sorry I can’t take you upstairs, they want me to wear socks”. Back to Pittwater next morning to see SS Golliwog, a reconstructed 48’ 1910 Admiralty steam pinnace complete with its original triple expansion steam engine, which Jumbo was having built in Huon pine and teak by Lars Halvorsen and Sons. “Sorry we can’t steam her; we have a problem with jellyfish being sucked into the water intakes – looking for a solution”.

As a special favour Jumbo was allowed to moor Golliwog amongst the pristine RPAYC yacht fleet, so long as it did not leak any oil. This required Jumbo to mop up the bilges with a bucket and sponge each morning. Bobbing up and down at anchor was his Dragon Class racer ‘Sama’ used for competition each Wednesday. Seemingly like everything he owned, this too was modified with an extra 4 feet added to the mast and half a ton of lead to the keel – it either went like the ‘clappers’, or broke. In 1946, ’47 and’48 he been a crew member on the 65’ ‘Morna’ for three of her wins in the Sydney to Hobart yacht race. She was the largest yacht on Sydney Harbour.

Boats done with, it was back to the house to check out the latest motoring project and to admire the tower clock from the Sydney cricket ground which was at repose along the back wall of the garage waiting for Jumbo to re-engineer it so that, through a system of pulleys, he could have it operating above his garage without the need for a fifty-foot tower. A ‘Flying Scotsman’ locomotive name-plate was on a wall behind his work bench – a reminder of an intended trip across America by steam on the ‘Scot’ that did not come to fruition. Various cars were tried out on the local roads, and on one occasion the writer was deputised to drive his supercharged MG TC at Amaroo hill climb. Saturday night was interesting – the guest bedroom was adjacent to the clock-room which housed most of Jumbo’s 65 clocks. As a couple of hours on Sunday morning were devoted to clock winding, many of the clocks were either fast or slow by Saturday. This meant that the would-be sleeping guest was subjected to an aural barrage of whirrings, dings, dongs, clunks and cuckoos.

Steam engines remained an interest and on one occasion Peter Latreille had the writer bring his model beam engine to a Saturday night dinner at which Jumbo was a guest. Of course, the engine was fired up during an intermission in the eating and drinking. Jumbo was duly impressed until he slowed the engine by laying a finger on the flywheel, announcing “It’s down on power, is the valve timing correct?”

As can be imagined, Jumbo had a wide circle of friends including Amherst Villiers of Bentley supercharging fame, Mike Hailwood, Donald Campbell, Briggs Cunningham, Tom Wheatcroft, Bob Chamberlain and Phil Irving. In Australia Phil was his go-to engineer and the two of them assisted at Donald Campbell’s land speed record on Lake Eyre; they operated a milling machine used to level the course. When in Melbourne Jumbo delighted in attending Lou Molina’s legendary Monday lunches, the fare being served in the lube bay of his mate Silvio Massola’s service station; the table being a giant board painted and shaped to represent a Bugatti badge placed on top of a partially raised car hoist.

Jumbo had an eye for the ladies. Peter Latreille recalls a visit to Hove To on his honeymoon with Ann who was wearing an ultra-short miniskirt – Jumbo took one glance and suggested she might like to take a seat in the monoposto Frazer Nash. Bob Chamberlain recalled a visit to Warrandyte to see Phil Irving and his partner Edith was also wearing a miniskirt and had her hair dyed red. Jumbo availed himself of the opportunity to confirm that the ‘curtains did not match the carpet’.

Most of Jumbo’s cars are worth special mention – indeed they were all ‘specials’ having been modified in some way to suit his taste; even his tow car was a blacked-out 3500 Rover, devoid of all external ornament or badging. Some of his cars were extra-special and will be dealt with in some detail.

The D-type Jaguar, OKV 1.

The Le Mans D-type was bought by Hamilton from Jaguar after the event and was displayed at the Paris Motor Show. It suffered accident damage on its way back to England and it was in this state that Jumbo bought it, subsequently modifying it to his taste for high-speed touring. This revamping was carried out under the guidance of Jaguars racing team manager Lofty England. A full width windscreen was fitted together with a habitable passenger seat, a door and luggage space sufficient for a picnic basket, thus sacrificing some petrol tank capacity. It became the inspiration for the Jaguar XK SS.

One of its high-speed journeys from Sydney to Melbourne was conducted in January heat – the external exhaust pipes below the passenger side door added to the heat stress. On arrival in Melbourne Jumbo and his passenger, New Zealander Gavin Bain, visited Peter Menere in his Pier Garage in Brighton to see if there was a way to relieve the heat in the passenger seat. Peter’s solution was a car scuttle ventilator let into the floor and controlled by a cable. Gavin laughs when he sees replica XJ SSs with this ‘authentic’ detail.

Gavin recalls another high-speed trip from Sydney to Adelaide. Jumbo: “We will average 60mph and do 60 minute ‘watches’”. With Gavin at the wheel, Jumbo would then go instantly to sleep in the passenger seat, only to wake almost exactly one hour later, exclaiming “It must be time for my watch”. He had not lost his seafaring habits.

A very much slower trip for the D-Type was when it was used as support vehicle to a steam traction engine being moved to Ted Lobb’s property at Grenfell in the Riverina – the average speed would have been less than 6 mph, not 60. Jumbo’s companion for this trip was the legendary ‘Bunty’ Scott-Moncrieff, dressed in full tropical kit including ‘Bombay’ bloomers and topped by a pith hat.

The writer continues to regret a missed opportunity to travel in the Jaguar to the famous Mont Ventoux hill climb in Provence. In 1965 he had been invited to visit Jumbo at his cottage in Braintree, England. The purpose of the visit was to authenticate the Type 50 Le Mans Bugatti for a potential buyer in USA. “Would you like to come to Mont Ventoux in the D-Type?” At that time, not knowing Jumbo well and being shy and penniless, the offer was declined with visions of embarrassment through an inability to pay our way. On closer acquaintance with Jumbo at a later date, we realised that flash hotels were not for him and that the trip would have been conducted with the minimum expense.

A record breaking 3/4½ Bentley.

Purchased by Jumbo in Melbourne, this car was used extensively for commuting in Australia. In September 1974 he undertook another high-speed Sydney-Adelaide trip with his friend and Jaguar guru Ian Cummins as passenger with Neville Webb providing back-up in one of Jumbo’s Porsches. The 1043-mile trip took 20 hours at an average speed of 52 mph – an exceptional speed for a vintage car.

When on a rally with Jumbo one often saw his car parked by the road-side in the late morning. On stopping there would an invitation to join him for ‘elevenses’ – coffee from a Thermos which was “improved” by a generous shot of rum – another naval tradition.

The turbo-charged 8-litre Bentley record breaker.

In 1946 Jumbo found an 8-litre Bentley that had been converted into an ambulance. 100 pounds was exchanged and a speed-record car envisaged. His original 3-litre Bentley chassis was shortened and boxed in, hydraulic brakes and telescopic shock absorbers were added and the 8-litre engine was overhauled; a light two-seater body completing the package. A mean speed of 136.4 mph at the 1962 Antwerp speed trials might have satisfied some as an adequate speed for a vintage car – but not for Jumbo, as it did not break the Bentley record previously set by Forrest Lycett with his 8-litre.

Amongst his extensive world-wide list of friends was Wilton Parker, the Vice-President of the Garret Corporation. Not since the Lockheed P38 fighter had turbochargers been used for petrol engines. The 8-litre engine was rebuilt again with a new, enlarged crankshaft, and Phil Irving designed connecting rods, forged in Melbourne, no doubt with help from Bob Chamberlain. With Jumbo, living in Australia, the car in England and the turbo arrangements being finalised in the USA, the logistics in the days of snail-mail must have been huge.

In spite of these difficulties, it all came together in a most satisfactory way with 550 bhp showing on the dynamometer at 4,500 rpm. This was sufficient to hurl the beast down an Autoroute near Ghent in Belgium at 164 mph one-way and a two-way average of 158.2 mph over one kilometre. Jumbo said that he was faster than all the Ferraris; there must have been a lot of dropped jaws!

Jumbo married for the only time in 1973 to Kathleen who was a car enthusiast and had been secretary to Chris Shorrock of supercharger fame. For the first time he was forced to wear socks on more formal occasions – a real concession to love. Jumbo died in 1983 and in October 1984 a two-day auction of 733 lots from his collection was held in Sydney consisting of ‘A unique and most important collection of Vintage and Thoroughbred Cars and Motorbikes, Automobilia, Steam Models and Artifacts, Clocks and Horological Items, Marine Models. Flight – Aircraft engines and Models’, according to the auction catalogue.

They don’t make’m like that anymore.

Etcetera…

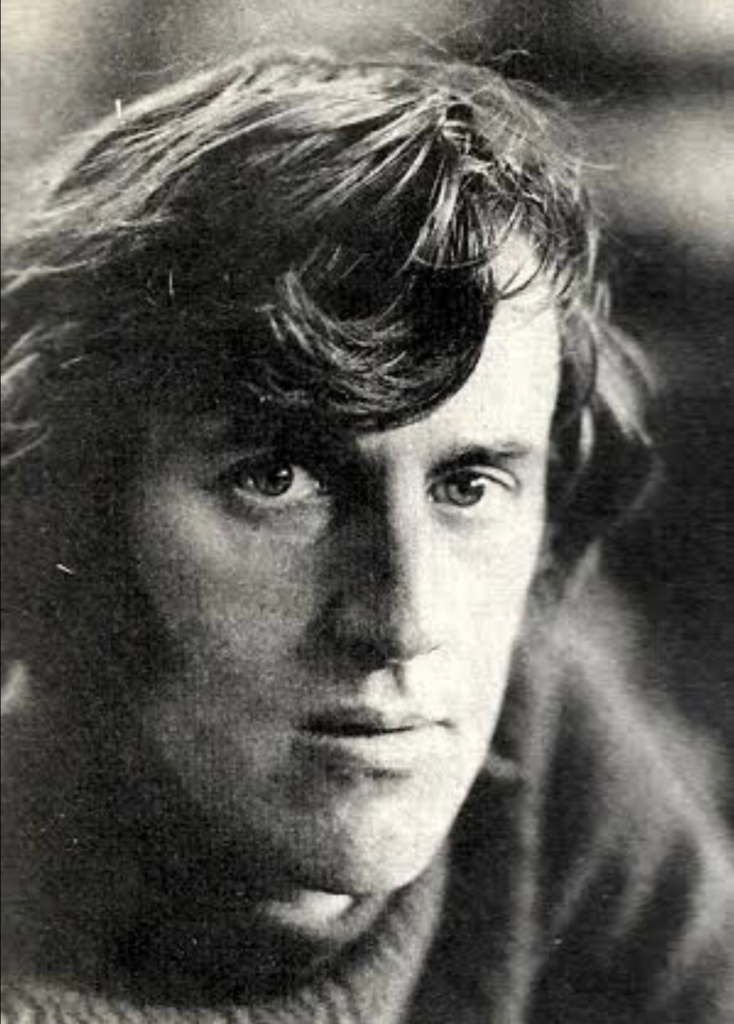

This is what some coarse Australians perhaps describe as an English Peach. If you avert your eyes northwards, Jumbo’s Blower Bentley is at the rear.

Credits…

Special thanks to Paul Cummins for the fantastic images from Dad, Ian Cummins Collection, Bob King, Gavin Bain, Tom King

Tailpiece

Doug Nye relates the following tale about Jumbo: On one Bugatti Rally in France, ‘Jumbo’ suffered constant trouble with a sinking carburettor float. At the Chateau Hotel lunch stop he tore down the troublesome carburettor, removed the punctured float and took it into the Hotel kitchen, where he wanted to boil it in a saucepan of water, to vaporise the methanol fuel which had filled it, so he could solder the hole and return his Bugatti to clean running.

With many hand signals and much volume, he explained to the Chef what he wanted to do, and he was assigned a gas ring, a saucepan full of water, and some tongs. But what ‘Jumbo’ had overlooked, and what the Chef was not warned of, was the explosive nature of vaporised methanol.

Laid out in that kitchen, ready for service, were plate after plate of cherishingly-crafted hors d’oeuvres, many in aspic or decorated with mayonnaise. But as ‘Jumbo’s fuel-filled carburettor float reached the critical temperature; methanol gas began to bubble from its puncture. ‘Jumbo’ lifted it from the saucepan whereupon, with a penetrating whistle, a fine spray of heated methanol shot out as if from a garden sprinkler. That airborne spray was instantly ignited by the lighted gas ring.

Deafened, dazzled by the flash, the kitchen staff stumbled around, tall hats blown off. And – worse – the blast had filled the air with floating ash, which began to settle on those exquisitely crafted hors d’oeuvres. The panic was like a Marseilles bus queue in the rush hour.

And from it all strode the majestic, Britannic, figure of ‘Jumbo’ Goddard, triumphantly clutching his dry, and empty, carburettor float in those borrowed tongs.

Within minutes his Bugatti was running clean – which is more than could be said for the Chateau Hotel’s kitchens.

Finito…