(S Dalton Collection)

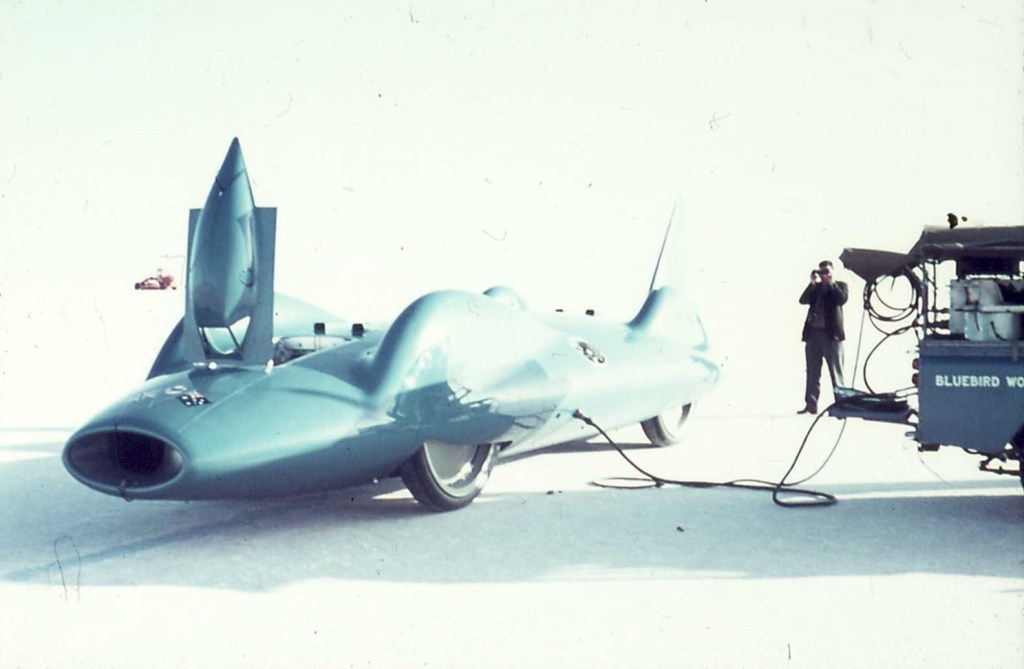

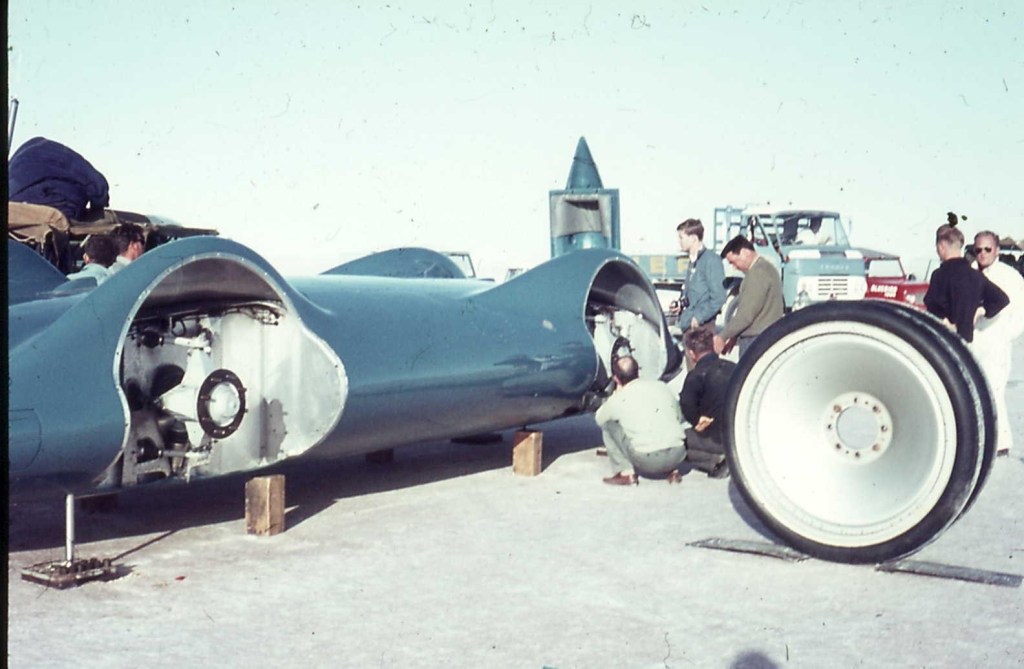

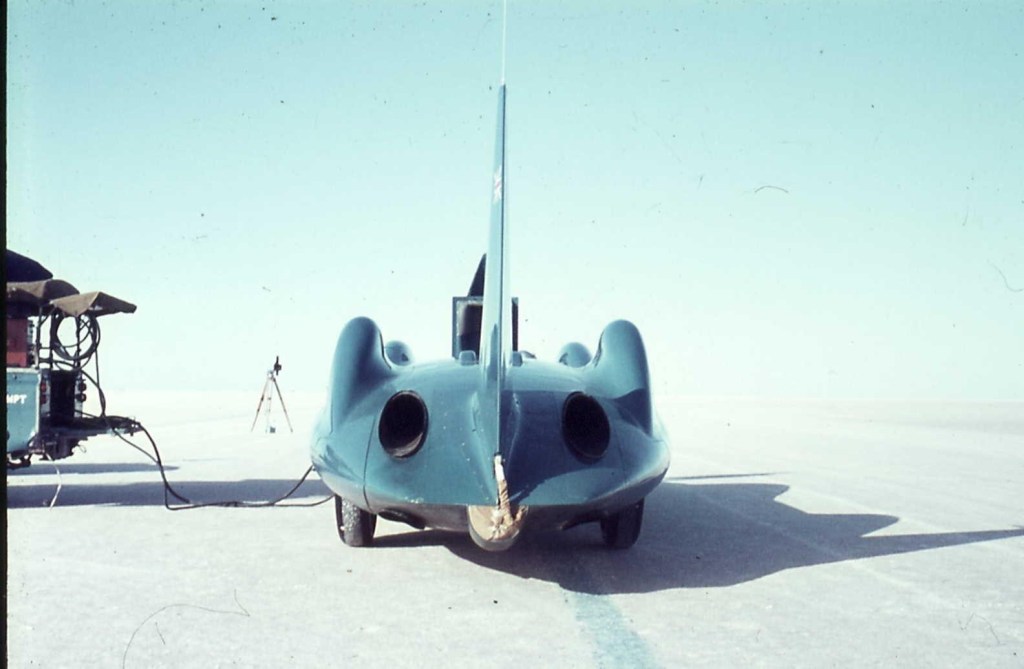

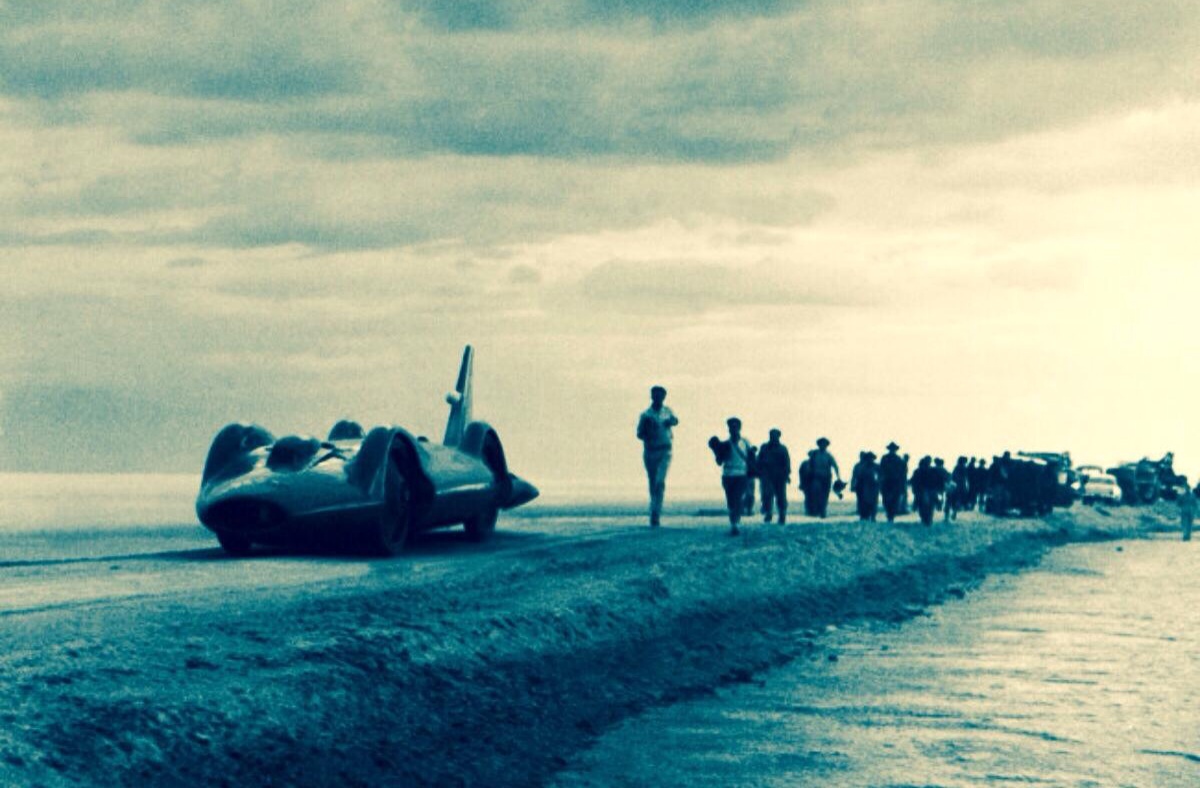

(S Dalton Collection)Bluebird Proteus CN7 and its little brother, Elfin Catalina Ford chassis #6313 during the 1963 unsuccessful attempt to set the Land Speed Record at Lake Eyre, South Australia…

The driver of the Elfin Catalina is Ted Townsend, a Dunlop tyre fitter. The car was built by Garrie Cooper and his artisans at Edwardstown, an Adelaide suburb for Dunlop Tyres to use on the Lake Eyre salt to assist in determining certain characteristics of the tyres fitted to Donald Campbell’s Bluebird during 1963/4.

The Elfin Catalina’s normal use was in Formula Junior or 1.5-litre road racing events. In LSR test application it was fitted with miniature Bluebird tyres and driven over the salt to determine factors such as the coefficient of friction and adhesion using a Tapley meter.

“The Tapley Brake Test Meter is a scientific instrument of very high accuracy, still used today. It consists of a finely balanced pendulum free to respond to any changes in speed or angle, working through a quadrant gear train to rotate a needle round a dial. The vehicle is then driven along a level road at about 20 miles per hour, and the brakes fully applied. When the vehicle has stopped the brake efficiency reading can be taken from the figure shown by the recording needle on the inner brake scale, whilst stopping distance readings are taken from the outer scale figures.”

It’s generally thought the Elfin was running a (relatively) normal pushrod 1500cc Cortina engine with a Cosworth A3 cam and Weber DCOE carburettors for the Bluebird support runs.

And yes, the number of Elfin’s chassis was 6313. Was Donald Campbell aware of this? Certainly that could explain to the deeply superstitious man how on earth torrential rain came to this vast, dry place where rain had not fallen in the previous 20 years.

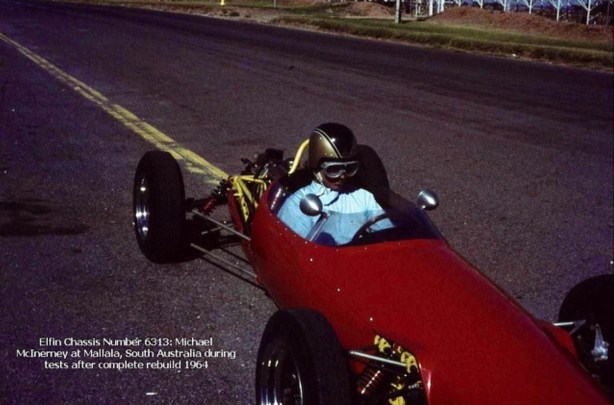

Dunlop’s Ted Townsend aboard the company Elfin Catalina. Car fitted with 13 inch versions of the 52 inch Bluebird wheels and tyres. Photo at Muloorina Station perhaps (Dunlop)

Dunlop’s Ted Townsend aboard the company Elfin Catalina. Car fitted with 13 inch versions of the 52 inch Bluebird wheels and tyres. Photo at Muloorina Station perhaps (Dunlop) (S Dalton Collection)

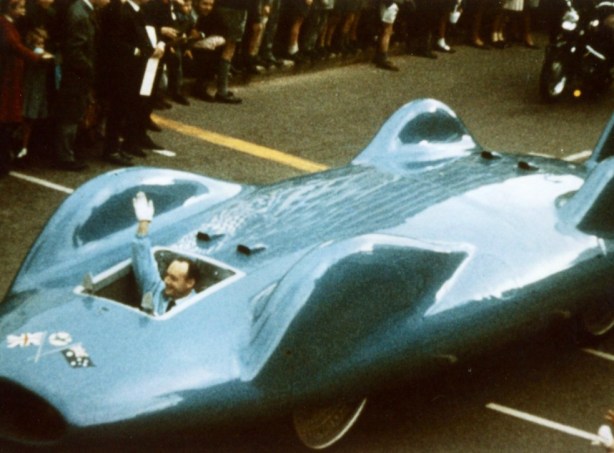

(S Dalton Collection)Australian motoring/racing journalist, racer and rally driver Evan Green project managed the successful July 1964 record attempt on behalf of Oz oil company Ampol, who were by then Bluebird’s major sponsor. He wrote a stunning account of his experience that winter on the Lake Eyre salt which was first published in Wheels April 1981 issue.

His account of Andrew Mustard and his teams contribution to the project is interesting and ultimately controversial from Campbell’s perspective.

Andrew was Dunlop’s representative during the 1963 Lake Eyre campaign, he returned in 1964 as a contractor with the very large responsibility for the tyre preparation and maintenance of the circa 22 km long salt track.

Green describes the incredibly harsh conditions under which the team worked “…Mustard…spent weeks with his men on the salt, working in the sort of reflected heat that few people could imagine let alone tolerate…Men frozen at dawn were burned black at midday. Lips were cracked and refused to heal. Faces set in leathery masks, creased by the wrinkles of perpetual squints.”

Evan Green picks up the challenges the track team faced, “The maddest thing is what’s being done to the track,” said Lofty Taylor, the gangling leader of the refuelling team. Lofty worked for Ampol, and I’d known him since the Ampol Trial days. l had enormous respect for his opinion. He was practical, versatile, prepared to move mountains if asked and yet able to detect the faintest whiff of cant at long distance.

He admitted he knew nothing about grading salt but pointed out that neither did anyone else, for the science of building record tracks on salt lakes was in its infancy. And he reckoned he knew as much about it as anyone else.

“They’ve been cutting salt off the top all the time,” he said. “All that grading and cutting is weakening it, and bringing moisture to the top.”

“What would you do, Lofty?” “Leave it alone for a while. Let the crust heal and harden.”

The track squad was ruffled. The problem, they said, was due to the constant interruptions to their work. They couldn’t get the surface right with the car (Bluebird) running every other day and cutting grooves in the salt. So runs were suspended. Andrew Mustard’s team would pursue their theories and have a clear week to try to bring the track up to record standard. Donald took some of the crew to Adelaide, for a few days break and all seemed calm. In fact, a major storm was brewing.

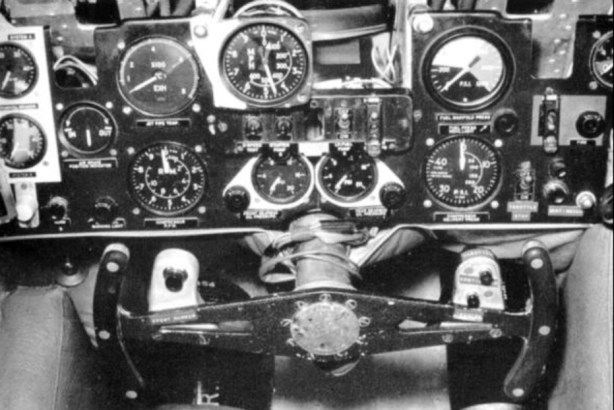

Massive 52 inch wheels and Dunlop tyres, the weight was huge, note the neat hydraulic lift to allow their fitment (unattributed)

Massive 52 inch wheels and Dunlop tyres, the weight was huge, note the neat hydraulic lift to allow their fitment (unattributed) (F Radman Collection)

(F Radman Collection) Andrew Mustard aboard the Elfin on the salt- note Catalina’s rear drum brakes (Catalina Park)

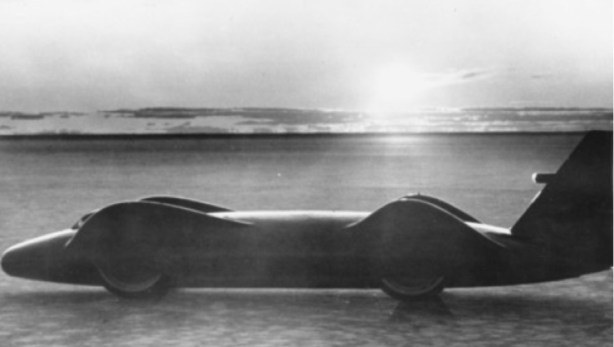

Andrew Mustard aboard the Elfin on the salt- note Catalina’s rear drum brakes (Catalina Park)“Mustard had brought an Elfin racing car to the lake. It was fitted with tyres that had scaled-down versions of the tread being used on Bluebird. He drove it to test such things as tread temperature and the coefficient of friction of the salt surface at different times of the day.

He usually drove the little single-seater down the strip before Campbell made a test run. On one occasion, he was driving the Elfin up the strip when Campbell was driving the Bluebird down the strip and the world’s highest speed head-on collision was avoided by a whisker, with a sheepish Mustard – spotting the rooster tail of white salt spray bearing down on him – spinning off the track.”

“One day during the lull, Ken Norris (Bluebird’s designer) and I went to the lake to see how the track work was progressing. To our astonishment, we found the CAMS (Confederation of Australian Motor Sport) timekeepers and stewards assembled at their record posts,” wrote Green.

“Andrew’s going for his records,” one of them said, and, seeing our bewilderment, gave us that ‘don’t tell me you don’t know about it look’. It seemed there had been an application made for attempts on various Australian class records for categories suiting the Elfin. Neither Ken nor I knew anything of it. Nor, it seemed, did Campbell, and when he returned that night there was an eruption. The track squad was sacked and Lofty Taylor given the job of preparing the strip.”

“What do you suggest?” I asked Lofty. “We should all go away for a couple of weeks and let the salt alone.”

Enjoy Greens full story of this remarkable endeavour of human achievement, via the link at the end of the article, but lets come back to Mustard and the Elfin, he wasn’t finished with it yet!

When the 1964 Bluebird record attempts were completed, Mustard, of North Brighton in Adelaide bought the Elfin from Dunlop.

It was in poor condition as a result of its work on the Lake Eyre salt, with the magnesium based uprights quite corroded. It was repaired over the end of 1963-64 and a single Norman supercharger fitted.

The car was then raced at Mallala race and for 1500cc record attempts in 1964 using the access road alongside the main hangars at Edinburgh Airfield (Weapons Research Establishment) at Salisbury, South Australia. The northern gates of the airfield were opened by the Australian Federal Police to give extra stopping distance. By then the specifications of the Norman supercharged Elfin included;

• a single air-cooled Norman supercharger driven by v-belts developing around 14psi. The v-belts were short lived, burning out in around thirty seconds,

• four exhaust stubs, with the middle two siamesed,

• twin Amal carburettors,

• a heavily modified head by Alexander Rowe (a Speedway legend and co-founder of the Ramsay-Rowe Special midget) running around 5:1 compression and a solid copper head gasket/decompression plate. The head had been worked within an inch of it’s life and shone like a mirror. The head gasket on the other hand was a weak spot, lasting only twenty seconds before failing. As runs had to be performed back-to-back within an hour, the team became very good at removing the head, annealing the copper gasket with an oxy torch and buttoning it all up again inside thirty minutes.

The Norman supercharged Elfin, operated by Mustard and Michael McInerney set the following Australian national records during it’s Salisbury runs on October 11, 1964:

• the flying start kilometre record (16.21s, 138mph),

• the flying start mile record (26.32s, 137mph), and

• the standing start mile record (34.03s, 106mph).

This was not 6313’s only association with Norman superchargers. The Elfin was later modified to have:

• dual air-cooled Norman superchargers (identical to the single Norman used earlier), mounted over the gearbox. The superchargers were run in parallel, with a chain drive. The chain drive was driven by a sprocket on the crank, running up to a slave shaft that ran across to the back of the gearbox to drive the first supercharger, then down to drive the second. The boost pressure in this configuration had risen to 29psi,

• two 2″ SU carburettors (with four fuel bowls) jetted for methanol by Peter Dodd (another Australian Speedway legend and owner of Auto Carburettor Services),

• a straight cut first gear in a VW gearbox. The clutch struggled to keep up with the torque being put out by the Norman blown Elfin, and was replaced with a 9” grinding disk, splined in the centre and fitted with brass buttons, it was either all in, or all out!

In twin Norman supercharged guise the racer was driven by McInerney to pursue the standing ¼ mile, standing 400m and flying kilometre records in October 1965. Sadly, the twin-Norman blown Elfin no longer holds those records, as the ¼ mile and flying kilometre (together with a few more records) were set at this time by Alex Smith in a Valano Special.

The day after the 1965 speed record trials (Labour Day October 1965), McInerney raced the twin-Norman supercharged Elfin at Mallala in Formule Libre as there was insufficient time to revert the engine back to Formula II specifications. The photo above shows McInerney at Mallala.

The car was used for training South Australian Police Force driving instructors in advanced handling techniques, and was regularly used at Mallala and other venues (closed meetings for the Austin 7 club, etc).

It was sold by Mustard to racer/rally driver Dean Rainsford in 1966, by then without the Norman supercharger it ran a mildly tuned Cortina engine. In the ensuing 26 years it passed through nine more owners before Rainsford re-acquired it in 1993. After many years of fossicking he found the original 1965 Mustard/McInerney supercharged engine but sadly without it’s Norman supercharger.

The Elfin is retained by Rainsford and is often on display in his Adelaide office. The car made a rare public appearance at Melbourne’s 2014 Motorclassica to celebrate the 50-year anniversary of Campbell’s land and water speed records set in Australia. The car was amongst other Campbell memorabilia.

Evan Green: ‘How Donald Campbell Broke The World LSR on Lake Eyre’…

Etcetera…

Credits…

Article by Evan Green originally published in Wheels magazine April 1981, Andrew Mustard thread on The Nostalgia Forum particularly the contributions of Stephen Dalton, Fred Radman, Theotherharv and Mark Dibben. Stephen Dalton, Fred Radman and Catalina Park Photo Collections, Dunlop

Tailpiece: Elfin Catalina Ford ‘6313’, Motorclassica 2014…

(Pinterest)

(Pinterest)Finito…