(oldracephotos.com.au)

Brian Bowe settles himself into his Elfin Catalina Ford in the Baskerville paddock, 1966…

There is no such thing as an ugly Elfin, this little car looks a picture in the bucolic surrounds of Tasmania. Garrie Cooper’s first single-seater racing cars were built off the back of his front-engined ‘Streamliner’ sportscars success.

The pace of these Catalinas was demonstrated by Frank Matich and others, they sold well with twenty FJ’s/250 Production/275 and 375 Works Replicas built from 1961 to 1963.

This chassis was raced by Melbourne single-seater, sportscar and touring car ace Brian Sampson and was powered by a Ford Cosworth 1.5 litre pushrod motor.

It was bought by Bowe and ‘was Dad’s first factory racing car having competed in specials before that’ John Bowe said.

‘In fact had I had my first drive of a racer in this car at Symmons Plains in private practice. I was twelve, and just about to start high school!’ ‘In discussions with Dad in the weeks before i’d worked out how many revs in top was 100 mph and did just that- when he realised how fast I was going he stood in the middle of the track and flagged me down. Furious he was! Happy carefree days’.

Indeed, John Bowe, by 1976 was a works Ansett Team Elfin F5000 driver, the Bowes were an Elfin family, not exclusively mind you. JB raced an Elfin 500 FV, 600FF and 700 Ford ANF3 en-route to his F5000 ride- and 792 and GE225 ANF2 cars as well.

Lindsay Ross identifies Arthur Hilliard’s Riley Pathfinder racer and towcar at the rear right of the shot by the paddock fence. The blue sporty is Bob Wright’s Tasma Peugeot.

A quickie article about the Bowe Catalina became a feature thanks to Ed Holly posting online some of the late, great Australian motor racing historian, Graham Howard’s photo archive. Specifically shots of the prototype Elfin Formula Junior taken at the time of its birth at the Edwardstown factory and subsequent public launch at Warwick Farm on 17 September 1961.

As a result we can examine these important Elfins in far more detail than I had originally planned, including a contemporary track test by Bruce Polain and owner/driver impressions from Ed.

Bruce Polain testing the Elfin FJ Ford at Warwick Farm in September 1961 (G Howard)

Bruce Polain wrote an article about his experiences that day in ‘Australian Motor Sports’- here are the salient bits of it, lets get Bruce’s contemporary impressions of the car before exploring the design in detail.

‘Taking it quietly over The Causeway, the little Elfin accelerated hard in third gear on the run to Polo Corner. Braking firmly, the speed fell away rapidly and I was conscious of considerable suspension movement as we ran over the bumpy entrance to the corner- a reminder that this was the flooded section of the track during the ‘first ever’ Warwick Farm.’

‘Nevertheless the poor surface failed to affect the comfortable ride and with a slight amount of understeer I swung the car into Polo. The handling characteristics were such that it gave understeer into a corner and a small amount of oversteer on the way out. This is quite a popular setup as through a corner it allows a fast entry to begin with, then as the steering is brought back to a neutral position, the oversteering tendency may be checked by applying more power to the rear wheels.’

‘…I enjoyed the delights of driving this beautifully constructed, fast and most forgiving racing car. The semi-reclining seat was more than comfortable and gave excellent lateral support, which is so important for ease of control in corners. At speed, steering was delightfully light and precise- you could eat your lunch with one hand. The lusty 1100cc Cosworth Ford engine was a wonderful propellent, easy to fire on the starter button, docile low down, yet bags of power when the accelerator was pressed.’

John Hartnett at Rob Roy Hillclimb in outer Melbourne’s Christmas Hills, Elfin Streamliner Coventry Climax chassis ’13’ (R Hartnett)

Cooper first commenced design of the FJ in 1960, as stated above, off the back of success of the Streamliner series of sports cars built from 1959 to 1963- twenty-three in all.

During this period the name out front of 1 Conmurra Avenue, Edwardstown, an Adelaide suburb, changed from ‘Cooper Motor Bodies’ to ‘Elfin Sports Cars’ which was indicative of the evolution of the then forty year old Cooper family business away from coach-building to the sexier but perhaps more challenging world of production racing cars.

Whilst nominally a Formula Junior design the twenty cars built had a range of engines fitted in capacities from 1 litre to 1.5 litres- Ford 105E, 116E, Peugeot, Coventry Climax FWA, Vincent HRD and Hillman Imp. They very quickly proved themselves capable of going wheel to wheel with the best cars from the UK- then THE hotbed of FJ development of course.

Lotus 18 like upright and rear suspension clear in this shot, as is the split-case VeeWee 36HP gearbox (G Howard)

The chassis of the car was a multi-tubular spaceframe of 16 and 18 gauge mild-steel tubing in varying diameters from five-eighths of an inch to an inch. It was strengthened by fitment of a stressed floorpan made of 19 and 20 gauge aluminium alloy.

Rear suspension was clearly inspired by the Lotus 18. It was fully independent with fixed length driveshafts which formed the suspension upper members. The lower wishbones incorporated adjustments for camber, toe and roll-centre height. ‘Driving and braking torques are controlled by long trailing arms (radius rods in more modern parlance) two per side.’ The uprights or ‘pillars’ are Cooper’s design of cast magnesium.

(G Howard)

Front suspension was period typical using unequal length upper and lower wishbones, note the Armstrong shock absorber, adjustable roll bar, unsighted is the Alford and Alder Triumph front upright. Steering was by way of a lightweight rack and pinion, the wheel wood-rimmed with a diameter of 13.5 inches. The brakes were Lockheed 2LS front and rear, the drums alloy bi-metal with radial finning.

(G Howard)

The engine was the Ford 105E which would become ubiquitous in the class. Cooper built the engine in Adelaide.

GC and his team designed and printed a very detailed brochure about the cars, no doubt with the racing car show in mind- giveaways are important at these events.

Its interesting to see how the two Ford Cosworth 105E engines offered were described.

The ‘Poverty Pack’ 250 Production Model FJ was a budget racing car fitted with pressed-steel wheels, cast iron rather than alloy bi-metal brake drums, non-adjustable shocks and non-close ratio gearbox.

It was offered with a Ford Cosworth 1000cc Formula Junior Mk3 ’85 Engine’ producing over 85bhp @ 7250rpm. ‘Every engine is dynamometer tested to at least this output before leaving the factory.’

The engine was fully balanced including crankshaft, flywheel and clutch, connecting rods and pistons.

Carburation was by two 40 DCOE Weber carbs on Cosworth manifolds- they were enclosed within the bodywork and fed by cold air from a duct on the lefthand side of the cockpit. The distributor was modified, the crankshaft pulley was ‘special’ for the water pump drive- visually the whole package was set off by a Cosworth light alloy rocker cover so the ‘psyching’ started in the paddock.

The ‘ducks guts’ 275 Works Replica Model offered the Cosworth Mk4 1100cc engine giving a minimum of 95bhp with ‘the average output of these engines 97-100bhp’.

The trick Mk4 differed from its smaller brother in that it had a bigger bore, special stronger connecting rods, special steel main bearing caps, bigger valves and different combustion chambers. ‘Replaceable valve guides are fitted as standard. Like the Mk3 these engines have a competition clutch, tachometer take-off, oil cooler union and special anti-surge sump.’

When the Ford Cosworth 1500cc engine was later fitted in the Works Replica model it was designated ‘375WR’.

(G Howard)

Gearbox was a split- case VW 36 horsepower which was modified in Adelaide and fitted with close ratios with ‘top gear running on a special roller bearing.’ A lightweight bell-housing mated the gearbox and engine, the final drive ratio was 4.42:1. The gear lever was mounted to the left of the driver. Note the different lower wishbone inner end alternative pickup points.

(G Howard)

When completed the little car (prototype car #4 ) was a handsome little beastie complete with full bodywork from nose to aft of the gearbox.

Success came quickly, its interesting looking at these photographs of the car being prepared for and shown at one of the track days to get the message out there. The motorsport shows the boys from Adelaide attended on the east coast would have been a significant exercise and cost at the time.

I don’t think Cooper’s commercial success in the toughest of markets in the toughest of industries- manufacturing has ever been truly recognised. I have mostly run and owned small businesses all of my adult life and know full well how hard it is to churn a dollar- Elfins survived and thrived for several decades under Garrie’s stewardship and then that of Don Elliott with Tony Edmondson at the coalface. I’ll stop the Elfin history there which is not to discount what followed, but from a production racing car perspective, that was it.

(G Howard)

The bodywork for the first three cars was made of aluminium by craftsman John Webb who was a constant throughout the whole of Elfin’s ‘glory days’- right up to the construction of the body of Vern Schuppan’s MR8C Chev Can-Am bodied F5000 machine.

On the fourth and subsequent cars the fibreglass bodywork was by Ron Tonkin- this comprised the nose, tail sections and cockpit surround. The side panels were of aluminium and ‘semi-stressed’.

Very pretty wheels were of magnesium alloy, 13 inches in diameter ‘with wide rims, (4.5 inches at the front and 5.5 inches wide at the rear) were finished in black anodite before machining. The wheels and uprights were Elfin’s design and cast by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation at Fishermans Bend in Melbourne.

‘Unsprung weight is further reduced by incorporating the wheel bearings directly in the front wheels.’

(G Howard)

(Ed Holly)

The photograph below is a very well known one to some of us of a certain age who bought or were given for Christmas 1973 (!) a copy of Bryan Hanrahan’s ‘Motor Racing The Australian Way’- this photo introduced the Elfin chapter. A decade or so later it was published in the ‘Elfin Bible’ Barry Catford and John Blanden’s ‘Australia’s Elfin Sports and Racing Cars’.

(G Howard)

Clustered around the Elfin are Tom Stevens and Norman Gilbert from BP- almost from the start Elfin supporters and sponsors, Cliff Cooper, Garrie Cooper and Murray Lewis ‘with the prototype Elfin FJ ready to leave for an interstate race meeting and motor show’.

The car was first shown at the Melbourne Racing Car Show in August 1961 and then raced for the first time at Warwick Farm that September in the hands of Arnold Glass, then an elite level competitor racing a BRM P48.

Barry Catford wrote that Arnold was in Adelaide to contest events at Mallala’s opening meeting on 18 August 1961 and had plenty of time on his hands to visit the team at Conmurra Road having fatally (for the car) boofed the BRM in practice. The story of that car is told here; https://primotipo.com/2018/03/16/bourne-to-ballarat-brm-p48-part-2/

Glass offered to drive the car on its race debut, something Cooper and BP’s Tom Stevens were keen to support.

The team of Garrie and Cliff Cooper, Tom and John Lewis took the car to Melbourne and then on to Sydney for its debut. Garrie drove the car initially and whilst it handled well the softly sprung machine bottomed over The Causeway and Northern and Western crossings (of the horse racing track underneath).

Modifications were made that night but several laps early in the day indicated the cars balance was lost- further changes were made, the cars poise had been regained in official practice when GC again drove.

Glass had no chance to officially practice but sweet talked the officials to allow him to run during one of the other racing car sessions- he was within three-tenths of Leo Geoghegan’s well developed Lotus 18 Ford FJ. The weary crew retired at 3 am on race morning having replaced the gearbox and clutch- which was slipping towards the end of the Glass lappery. All the hard work was rewarded with a second to Leo- not bad for the cars first race.

Keith Rilstone’s Catalina Ford ‘6317’ on its first day out at Mallala in very late 1963, factory records have it’s completion that November (G Patullo)

The prototype car, chassis ’61P1′ was sold to Adelaide businessmen and racers Andy Brown and Granton Harrison who had much success with it. Queenslander Roy Morris did well with his Coventry Climax FWA engined car- as did John McDonald’s 1350cc engined car- neither FJ legal of course.

One of the most commercially astute moves Cooper ever made was the appointment of up and coming- well ok!, he had well and truly arrived by then, Frank Matich as the works driver of three cars which were located at his Punchbowl, Sydney Total Service Station. An 1100cc chassis ‘625’, a 1500cc chassis ‘627’ and a Clubman fitted with another Cosworth engine of 1340cc. In addition Matich was appointed as Elfin’s NSW agent.

An interesting aspect is that in the process of deciding who to give the factory cars to, Matich tested the cars, as did Peter Willamson and David McKay with FM the quicker of the three. Perhaps Cooper’s gut feel as to the driver he wanted was validated by this process. The choices are interesting in that Williason was at the start of his career whereas David McKay was in the twlight’ish of his.

Mel McEwin #16 Elfin Catalina 1500 passes Andy Brown in the Elfin FJ Ford prototype during the ‘GT Harrison Trophy’, support race at the 1963 ATCC meeting. Keith Rilstone won the race in the truly wild Eldred Norman built Zephyr Spl s/c- McEwin was 3rd and Garrie Cooper 4th in another Elfin Cat 1500- I wonder if it was seeing the cars up close at this meeting that made up Keith’s mind to get with the strength and buy one! (B Smith)

Whilst Matich was new to single-seaters, his outright pace in various sportscars- Austin Healey, C and D Type Jags, Lotus 15 and 19 Climax was clear. For Frank the deal was a beauty as he had the opportunity to show his prowess in a new field. Catford wrote that FM’s only open-wheeler experience to that point was a few warm-up laps in Leo Geoghegan’s Lotus 20B Ford when it first arrived in Australia early in 1962.

Critically, Matich put Elfins front and centre to racers in Australia’s biggest market- New South Wales, with subsequent sales reflecting the success of Matich and others.

Cooper got a longer term benefit as Matich turned to him for his first ‘Big V8’ sportscar, the Elfin 400 Olds aka ‘Traco Olds’ in part based on GC’s design talents which he had experienced first hand in the small-bore machines listed above. Matich in turn proved the pace of the 400, outta the box, in winning the 1966 Australian Tourist Trophy in his third meeting with the car at Longford in March 1966.

The red Elfin was the Junior, the 1500 was green up until Frank decided to let the 1500 go, which went to Charlie Smith and the red car went from 1100 to 1500′ Ed Holly

Frank’s first meeting in the FJ cars was at Warwick Farm on 14 October 1962- Matich was fourth in the Hordern Trophy Gold Star event- in amongst and ahead of some of the 2.5 litre Coventry Climax engine cars, and despite a one minute penalty for a spin! (tough in those days!).

This was indicative of what was to come a fortnight later in the first Australian Formula Junior Championship held at the new Catalina Park circuit at Katoomba in the NSW Blue Mountains, 100 Km to Sydney’s west.

Frank Matich is shown below in the red Elfin FJ Ford alongside Gavin Youl’s Brabham BT2 Ford and Leo Geoghegan in a Lotus 22 Ford. The front row comprised the latest Brabham, Lotus and Elfin FJ’s- Leo’s Lotus was literally just off the plane. On row 2 is Clive Nolan’s 5th placed Lotus 20 Ford.

(B Miller)

Matich won the 30 lap race from Youl and Geoghegan in a weekend of absolute dominance , the win was the first of many Australian titles for Elfin and spawned the ‘Catalina’ name for this series of spaceframe chassis open-wheelers.

Catford notes the presence that weekend of Tony Alcock in the team- well known to Australian enthusiasts as an Elfin long-termer and close confidant of Garrie Cooper before going to the UK and returning to form Birrana Cars with fellow South Australian Malcolm Ramsay. International readers may recall him as one of the poor unfortunates to perish in the plane piloted and crashed by Graham Hill upon return to the UK after a French circuit test of the new Hill GH1 Ford F1 car.

Matich contested eight events hat weekend! in the two Elfins- FJ/Clubman and Lotus 19 winning six of them and placing in the other two.

Development work and evolution of the cars continued throughout their production life including incorporation of Triumph Spitfire disc brakes on the front- with Jack Hunnam fitting alloy racing calipers and discs to all four wheels of his car.

Lyn Archer’s Catalina at the Domain Hillclimb, Hobart in November 1964. Lyn raced the car successfully for a few years, sold it, and bought it back. Upon his death a few years back his family still owns it (R Dalwood)

Other notable drivers of Catalinas were Kevin Bartlett in the McGuire Family Imp engine car, Jack Hunnam, the Victorian Elfin agent won 12 races from 18 starts in his supposedly 165bhp 1500cc pushrod Ford engine disc braked car ‘6312’, before selling it to Tasmanian Lyn Archer. He won the 1966 Tasmanian Racing Car Championship in it and was timed at 150mph on Longford’s Flying Mile in 1965. Greg Cusack was quick in the car owned by Scuderia Veloce, winning the 1964 Australian Formula 2 Championship from David Walker’s Brabham and Hunnam’s Catalina. Other Catalina racers included Barry Lake, Keith Rilstone and Noel Hurd.

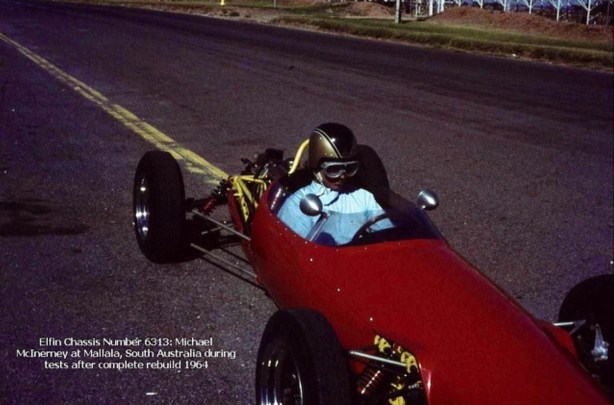

Perhaps the most unusual application of a Catalina was chassis ‘6313’ which was acquired by Dunlop UK for tyre testing to assist the Donald Campbell, Bluebird CN7 Proteus attempt on the World Land Speed Record at South Australia’s Lake Eyre in 1963 and 1964.

That effort is in part covered here but a feature on the Elfin Catalina aspects of it is coming soon- all but finished, https://primotipo.com/2014/07/16/50-years-ago-today-17-july-1964-donald-campbell-broke-the-world-land-speed-record-in-bluebird-at-lake-eyre-south-australia-a-speed-of-403-10-mph/

‘6313’ Ford on the Lake Eyre salt- steel wheels fitted with Bluebird Dunlops in miniature (F Radman)

This corker of a shot is by Gavin Fry- were it not for the presence of the Elfin Catalina on the trailer (who?) it could be an Australian summer beach scene, but it is an early Calder meeting (when?) (G Fry)

The Elfin Mallala was a very important car in the pantheon of Elfin’s history.

The twenty cars built provided solid cashflow for the Cooper family business, off the back of the solid start the Streamliner provided, the company now had a reputation for making fine single-seaters in addition to sporties.

Importantly Cooper had attracted some of the biggest names in Australia to his marque- Matich and McKay to name two. The Catalina ‘hardware’ also spawned a small run of mid-engined sportscars- the Mallala, of which five were built from late 1962 to early 1964.

Ray Strong, Elfin Mallala Ford, Huntley Hillclimb in December 1968. This design, derived from the Catalina, is one of the prettiest of all Elfins in my book- effective too (B Simpson)

Perhaps the only thing which suffered by virtue of this commercial success, albeit still limited capital base, was Cooper’s own driving career as he had neither the time or the spare cash to build a car for himself!

That would be remedied by the ‘Mono’ Type 100, his ‘radical’ single-seater which followed the conservative Catalina- and in which GC was very quick.

The Mono is a story for another time but is told in part here; https://primotipo.com/2018/10/18/clisby-douglas-spl-and-clisby-f1-1-5-litre-v6/ and here; https://primotipo.com/2019/03/22/elfin-mono-clisby-mallala-april-1965/

Garrie Cooper in Elfin Mono Mk2D Ford Twin-Cam ‘MD6755’ at Symmons Plains in 1967 (J Lambert)

The Owner/Driver’s Experience…

Ed Holly gives us the Catalina owner/drivers perspective…

‘The works 1500 or WR375 was the first of 2 Elfin “Catalina’s” that Frank Matich drove.

I bought chassis ‘625’ from Adam Berryman who had quite some success with it before me. As this was the first ever single-seater for me I had no benchmark to compare with, having raced MGA’s for about 7 years previously. It went on to give me success too including the Jack Brabham Trophy put up once a year by the HSRCA for Group M 1st place at their main meeting at Eastern Creek.

For me the transition to single seater was made very easy by this car and looking back there are a couple of reasons for that. Firstly in 2000 you could get very good Japanese Dunlops – a beautiful tyre and the car was shod with 450 front and 550 rear. This gave a very neutral feel to the car with the set-up fettled by Dave Mawer for me at that time.

The power was a great match to the chassis. As the engine only had a standard crank I revved it to 6,800 but the torque was tremendous, no doubt the 12.7 comp ratio had a lot to do with that. The gear-change and box were perfect, it had a VW C/R box and standard H pattern.

Race start would invariably see the car launch through the row in front, usually twin-cam Brabhams as they struggled with the dogleg gear-change from 1st to 2nd, the Elfin was a straight through change and very quick, and the engine torque allowed wheel-spin to be kept to a minimum and the power band came in at least 1500 rpm less meaning you were well on your way whilst they were still waiting for the torque to kick in.

Handling wise the car was viceless, the perfect first single seater – in fact I set a Group M class lap record at Eastern Creek with it at 1:45 and it took me about 5 years in my Group M Brabham BT6 (twin-cam 40 more bhp, 5 not 4 speeds and discs all round) to better that. Mind you the tyres as mentioned above were far inferior by the time the Brabham arrived and in fact I re-set the lap record on 10 year old Japanese Dunlops – the brand new flown in English ones being about 3 seconds slower that same weekend.’

Matich in ‘625’ gets the jump at the start from Leo Geoghegan and the nose of Frank Gardner at the 1963 Blue Mountains Trophy race at Catalina Park- Catalina/WR375, Lotus 22 Ford and Brabham BT2 Ford- all 1500 pushrods. Matich won from Gardner and Geoghegan (J Ellacott)

‘Years later having driven Elfin, Lotus 20, Brabham BT15, BT6, BT21C and BT21 replica – I guess I was in a position to make a judgement about the Elfin.

In my opinion Garrie got it perfect for the time. Loosely based on the Lotus 18 concept, it is a hugely superior car to the Lotus 20 that succeeded the 18.

I spoke at length with Frank Matich about the design and we both agreed that on paper it didn’t look all that wonderful, BUT, it was – the results Frank achieved with it were sensational, often beating the Climax 2.5 powered Coopers.

I’ve never driven a Elfin with 1100cc- but Frank did and with a Junior 1100 he knocked off Leo Geoghegan in a Lotus 20 1500 at Sandown. To me that shows that the Elfin was just a little ahead of the competition in that wonderful early 1960’s period. And that is my observation too.

Finally the big race- 20 laps at Catalina for the Formula Junior Championship 1962 where the Elfin was up against the brand new Lotus 22 of Leo Geoghegan’s and the just arrived from UK Brabham BT2 works car driven by Gavin Youl – and other FJ’s – the Elfin and Matich beat them all even after running out of fuel on the last corner!’

(S Dalton)

Events like Melbourne’s ‘Motorclassica’ are fantastic shows of classic and racing cars but they are celebrations of the past.

Its amazing to think that in the sixties, whilst the old stuff had its place, a significant part of a competition car show comprised exhibitions of contemporary, and in many cases Australian made racing cars.

Stephen Dalton provided the cover of the magazine for the 1964 ‘Melbourne Racing Car Show’ put together by Melbourne businessman/racers Lex Davison, the Leech Brothers and several others.

The event was held at the Royal Exhibition Building over three days, 13-15 August 1964, and is somewhat poignant in that it’s purpose was to assist Rocky Tresise’ girlfriend Robyn Atherton raise funds in the Miss Mercy Hospital Quest. Many of you are aware that ‘Ecurie Australie’ founder, Lex and his protege, Rocky, died six months later- Lex of a heart attack at the wheel of his Brabham at Sandown, and Rocky a week later at Longford in Lex’ older Cooper.

Stephen notes that cars displayed included MG, Aston Martin, Lotus, Ferrari, Cooper and many others. Elfin were represented by local agent, Jack Hunnam whose new Mono was on display only several days prior to its race debut at Calder.

Etcetera…

The following is a nice little human interest story ran in ‘Pix’ magazine about Garrie Cooper and Elfin in 1963- courtesy of the Elfin Sixties Sportscars Facebook page.

I’ve included it as it’s very much ‘on point’- Cooper, Catalina, Clubman and Matich.

(Ed Holly)

Charlie Smith in the ex-Matich Catalina at Mount Panorama in 1963, he drove the car well with success. Don’t know much about this guy, had a drive or two in the Mildren Lotus 23 Ford, intrigued to know more.

(S Dalton)

Andy brown loops his Catalina as fellow South Australian John Marston approaches aboard his- Shell Corner at Calder on 20 January 1963. Andy went on to own one of the most famous Elfins of all a few years later, the ‘F1’ Elfin T100 ‘Mono’ Clisby 1.5 V6.

(Ed Holly)

(Ed Holly)

The photographs above are the balance of the pages of the Elfin Catalina sales brochure produced for use at motor shows not shown earlier in the article.

Credits and References …

oldracephotos.com.au, Ed Holly Collection, ‘Australias Elfin Sports and Racing Cars’ Barry Catford and John Blanden, Fred Radman, Grant Patullo, John Ellacott, Dick Simpson, James Lambert Collection, Brenton Smith Collection, Brian Miller Collection, Reg Dalwood, Article by Bruce Polain in ‘Australian Motor Sports’

(Ed Holly)

One Man’s Hobby. Or is that Obsession?!…

When Ed Holly and I first communicated about this article he sent thru a few pics of some engines he had built. I thought ‘gees! that’s interesting and amazing!’, so here they are.

Ed advises on how his engine building career commenced.

‘Having had a lathe for many years, when I added a mill to the workshop I wanted to learn how best to use it.

As I didn’t have a restoration project at the time, the lightbulb in the head said build a model engine – I flew models as a kid and loved the diesels back then as you didn’t need to buy a battery to start them!

So I searched the web and selected a BollAero18 and set about making one, a 1.8cc simple diesel. Well it took a while to interpret the plans having no technical background requiring that. I steadily worked through the components and the big day came and blow me down it ran !

That sort of started a bit of an obsession till the next project arrived.

(Ed Holly)

Now 16 model diesels later I have certainly learnt how to use a mill- more than half the engines are to my design and the English ‘AeroModeller’ January issue published plans and a review of one designed for first up builds. I called it the Holly Buddy.

Plans and build for this engine can be found at https://protect-au.mimecast.com/s/jFvcCZYMxgU5nKmqFz21YC

For those into specifics – the aim is one or two tenths of a thou taper in the bore and a squeaky tight piston fit at tdc – that’s the ultimate fit for a diesel. The photo’s show an inline twin before and after assembly.’

So…set to it folks, you too can be a race engine builder!

(Ed Holly)

(Ed Holly)

Tailpiece: Elfin 275WR Ford 1100 FJ…

Simply superb cutaway drawing of the Catalina by Peter Wlkinson. Very few Australian racing cars have been so ‘dissected’ in this manner over the years which is a shame.

Mr Wilkinson’s work, I know little about the man, compares very favourably with his peers in England and Europe at the time. Ed kindly sent me this cutaway at high resolution- ‘blow it up’, you can literally see the Elfin’s pixie like face on the wheel caps!

Car specification is as per the text.

Finito…

(S Dalton Collection)

(S Dalton Collection) Dunlop’s Ted Townsend aboard the company Elfin Catalina. Car fitted with 13 inch versions of the 52 inch Bluebird wheels and tyres. Photo at Muloorina Station perhaps (Dunlop)

Dunlop’s Ted Townsend aboard the company Elfin Catalina. Car fitted with 13 inch versions of the 52 inch Bluebird wheels and tyres. Photo at Muloorina Station perhaps (Dunlop) (S Dalton Collection)

(S Dalton Collection) Massive 52 inch wheels and Dunlop tyres, the weight was huge, note the neat hydraulic lift to allow their fitment (unattributed)

Massive 52 inch wheels and Dunlop tyres, the weight was huge, note the neat hydraulic lift to allow their fitment (unattributed) (F Radman Collection)

(F Radman Collection) Andrew Mustard aboard the Elfin on the salt- note Catalina’s rear drum brakes (Catalina Park)

Andrew Mustard aboard the Elfin on the salt- note Catalina’s rear drum brakes (Catalina Park) (Pinterest)

(Pinterest)