(J Mepstead)

How many Repco Brabham Engines Pty. Ltd. race V8’s were built during the 1965 to 1969 period of the companies existence?…

Not sure that I know the answer in full.

Lets build a list which will be ongoing Work In Progress as we determine the number built, the car they were initially fitted to, a bit of history perhaps and the perfect world would be their ultimate destination inclusive of who owns them now.

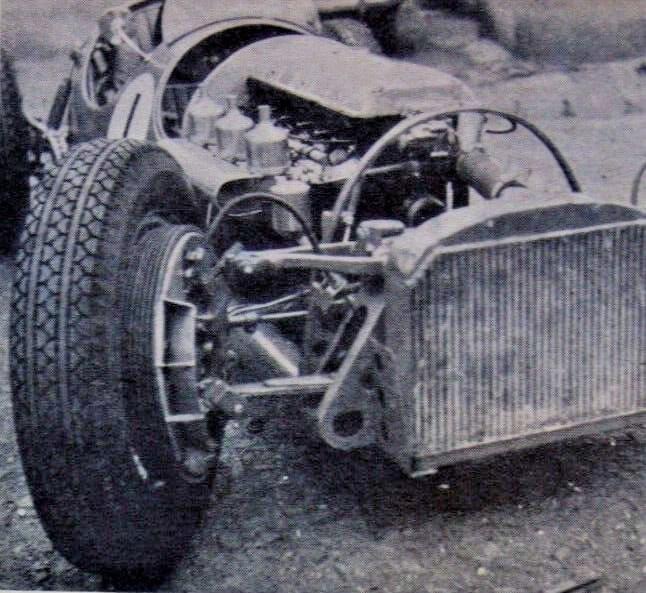

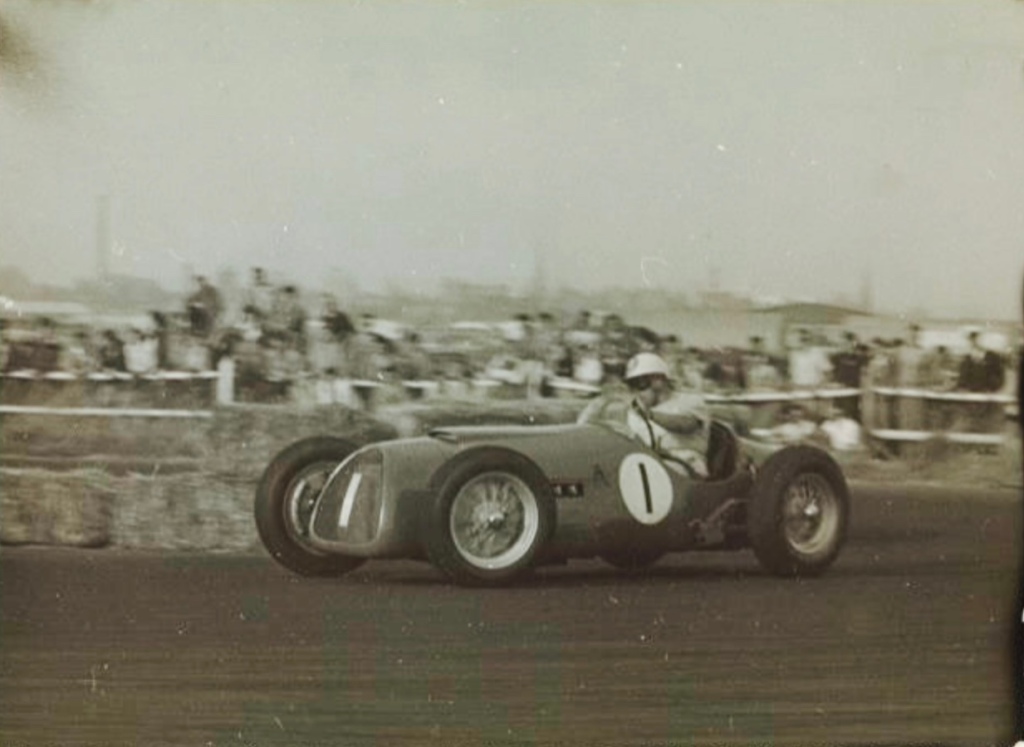

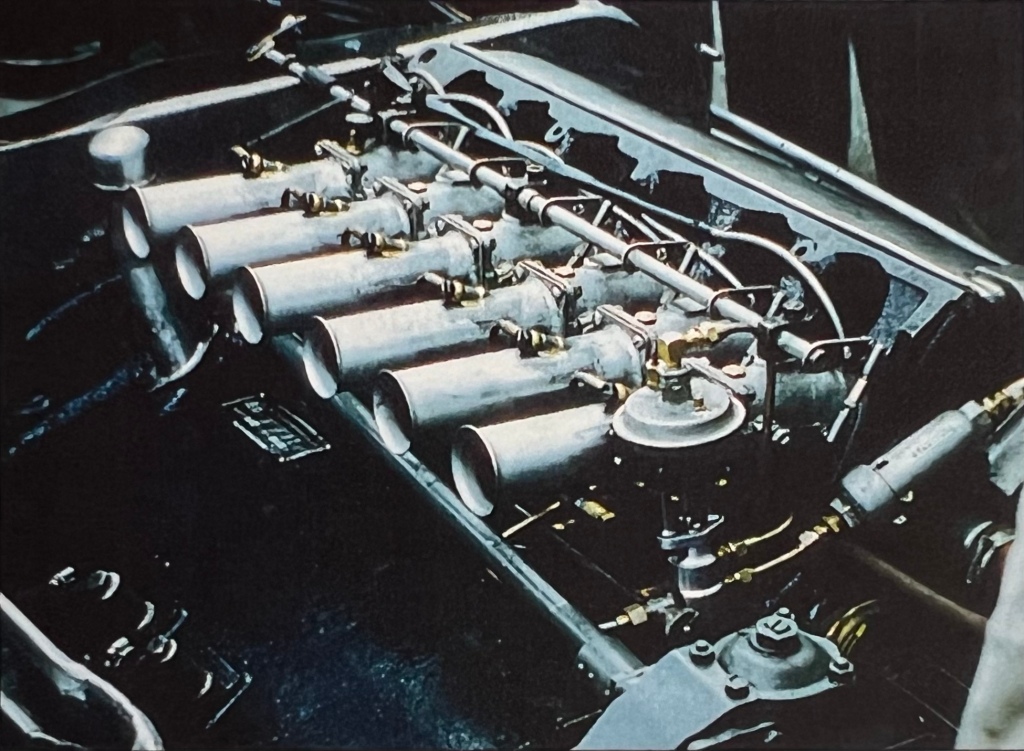

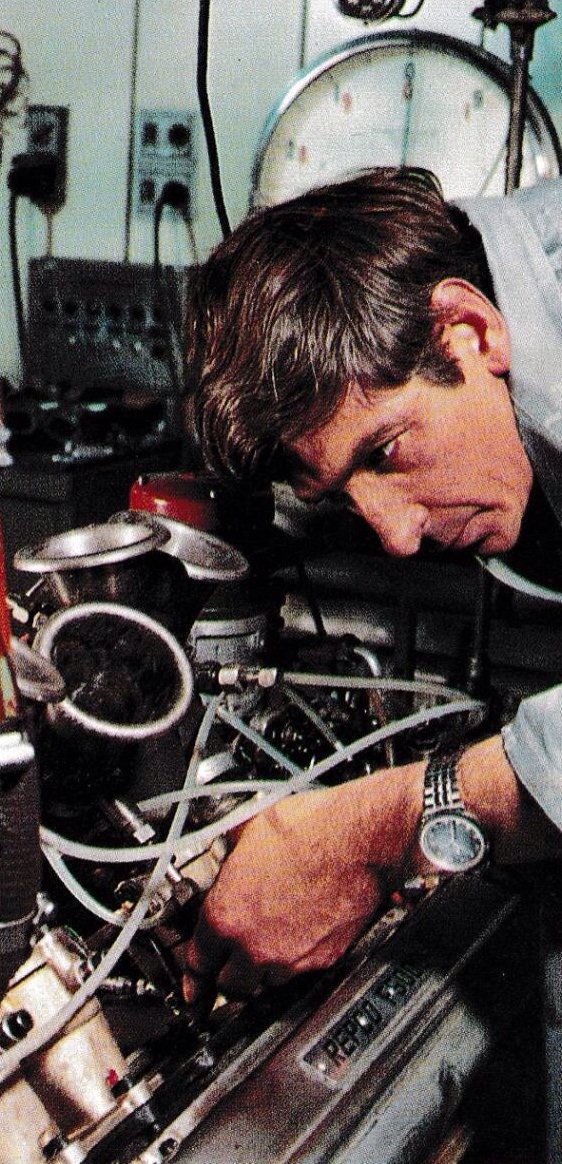

The article was stimulated by ex-RBE man John Mepstead, above, sending this photo of a very late 760 Series V8- the 4.8 litre ‘E41’ which was fitted to Frank Matich’s Matich SR4 and raced through 1969. ‘Shidday’, I thought, thats a pretty late RB Meppa is giving a tug! It must be towards the end of the production of the engines?

So, I had a bit of a fossick through Rod Wolfe’s suitcase of goodies and found a couple of source documents I knew were there to get us started. One is an ‘Engine Position’ list dated 17 July 1968, another is ‘Management Memorandum Number 1’ dated 30 June 1967.

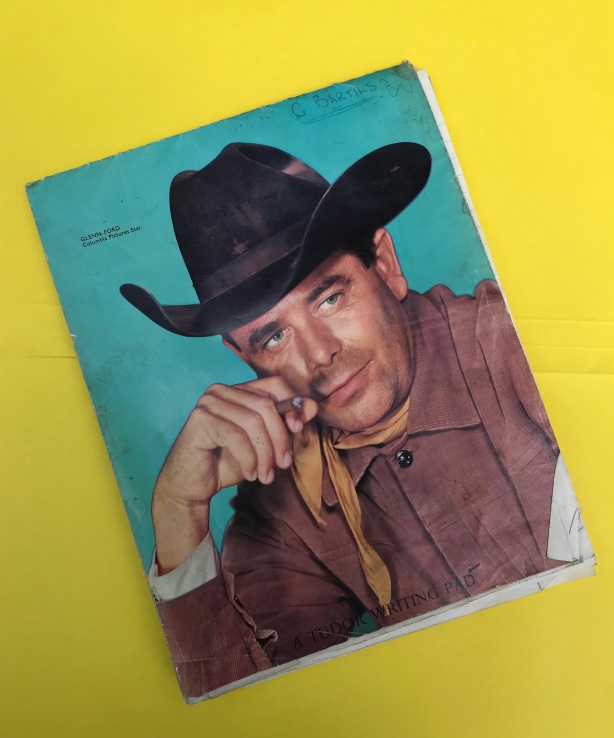

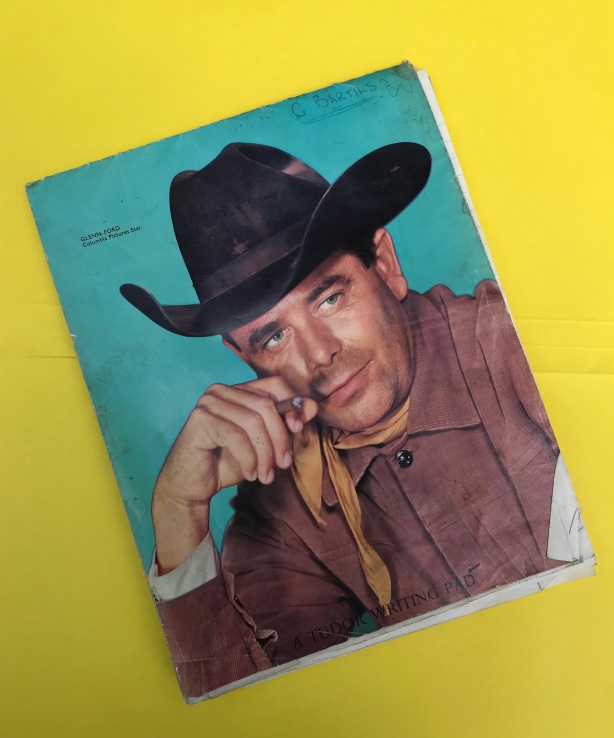

Rod also has Graham Bartil’s notebook of engine settings made when he was assembling or rebuilding them, so in a couple of cases we have the ‘birth-date’ of the engines. I love Graham’s use of branded Repco stationery below, the first record in this exercise book is on 20 June 1966 and the last on 27 July 1966.

Malcolm Preston, in his book cites particular engines as used in various cars or events.

(G Bartils- Wolfe)

Race motors are grandfathers axe of course- blocks and heads and other bits and pieces are replaced either as a matter of routine maintenance, as a consequence of a moment of destruction or an upgrade to the latest and greatest componentry.

So an engine- ‘E6-620’ may have started as a 620 but had its block replaced in 1967 with a 700 Series block- the 20 Series heads and timing chest etc will bolt straight onto the 700 block- and thus becomes ‘E6-720. Do you get my drift?

Given my articles so far do not cover all of the engine types built, we have only done 620 and 740 in detail there is a summary towards the end of this piece of each engine you can use as a ‘ready reckoner’ of what engine is what.

What started conceptually as a list of engines changed when I went searching for information and was reminded of the Facebook ‘veins of gold’ represented by dialogue between RBE folks which deserved to be captured permanently and packaged into some semblance of order.

There is some quite exquisite detail amongst the online badinage between Rodway Wolfe and Nigel Tait over about five years with others such as Michael Gasking, John Mepstead, David Nash and the late Don Halpin adding facts, perspective, anecdotes and flavour.

Then, as momentum built amongst a few folks Rodway went back through his diaries from 1967 to 1969 and came up with some wonderful- and in a couple of cases hugely important snippets, these bits start with ‘Rod’.

Denis Lupton gave me David Nash’s number a couple of weeks ago, but of course I hadn’t got around to calling him- he gave me a yell on 18 February offering the engine list assembled by the late Don Halpin- typed and dated 15 December 1972 but with additonal annotations by hand, who surely built more of these engines in the last fifty years than anyone.

As a consequence the piece is a big, long bastard at over 12,500 words. Ridiculous really, so grab a couple of ‘longnecks’ and a nice cold glass before the off!

Special thanks to all of those who have provided assistance in recent times or online some years back- very little of this article is from a book- such a publication does not exist.

Other Notes

I have put in build years as headings which are indicative rather than definitive but at least serve to help structure the article. The engine numbers do not all run ‘in sequence’ as much of the article had been written by the time I had the full list of numbers, and it is a big job to re-format.

This is Repco anoraks only stuff of course, I assume you will have read the links immediately below, that is I’m operating on the basis you have a base level of knowledge as I do not ‘join all the dots’ throughout.

Finally, by way of introduction any errors of commission or omission are mine.

Remember this piece is WIP- if you can add bits to the puzzle or knowledge of these wonderful bits of engineering do get in touch.

Homework before you start this piece are these articles on the RBE-620 Series;

‘RB620’ V8: Building The 1966 World F1 Champion Engine…by Rodway Wolfe and Mark Bisset

and; https://primotipo.com/2014/11/13/winning-the-1966-world-f1-championships-rodways-repco-recollections-episode-3/

and again; https://primotipo.com/2019/02/08/man-of-the-moment/

and this one on the RBE-640 and 740 Series;

‘RB740’ Repco’s 1967 F1 Championship Winning V8…

and this one; https://primotipo.com/2017/12/28/give-us-a-cuddle-sweetie/

To cut to the chase RBE Pty. Ltd. built about 51 engines, that is engines or part thereof allocated a number, Redco Pty. Ltd built 1, Don Halpin 2, plus various bibs and bobs which will become apparent via the responses this article attracts.

Finally, that RBE count does not include ‘special projects’ inclusive of the Repco-Brabham Pontiac Project…

Here we go.

(SMH)

The photograph above is Ron Tauranac and BT19 ‘620’, the 1966 championship winning combination, at the ‘Shifting Gear’ National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne exhibition in 2015.

Click here for an article about that fantastic gig; https://primotipo.com/2015/05/13/shifting-gear-design-innovation-and-the-australian-car-exhibition-national-gallery-of-victoria-by-stephen-dalton-mark-bisset/

1965-1966

RB620-E1

The very first 2.5 litre engine built in Richmond, first run on the dyno in March 1965 ‘Wade 185 camshaft’ noted in (undated sadly) Graham Bartil’s book entry.

It may well be he has transcribed the details of E1 into his book as a point of reference for another engine he was working on.

(G Bartils- Wolfe)

As at July 1968 it was a ‘mock up display engine’- which presumably means no gizzards inside.

No more on this engine as it’s build is well covered in one of the articles by Rodway and I referenced above.

David Nash owns E1 presently, built as a 4.4 litre 620, he plans to fit it to Peter Holinger’s first Repco engined hillclimber he also owns.

Repco Brabham engine #1 RB620 ‘E1’. This was the only engine fitted with Webers, this set of carbs were borrowed from Bib Stillwell, the Oz champion racer’s car dealership and race shop were in Kew, several kays from Doonside Street (Repco)

Phil Irving, Jack Brabham and Frank Hallam with Roy Billington fettling- Brabham BT19 Repco 620 2.5 E2 at Longford 1966

When I looked at this photo I thought ‘Shit! The only guy missing from the core 1966 Championship winning team is Ron!’ But its not quite that simple of course…

The Repco F1 engine program came about as one of a series of progressive motor racing steps starting with Dave McGrath’s purchase of Charlie Dean’s Replex business- the Repco Board did not decide ‘out of the blue’ to build a Tasman 2.5 / F1 3 litre engine.

Repco’s motor racing history can be characterised as having distinct phases as follows.

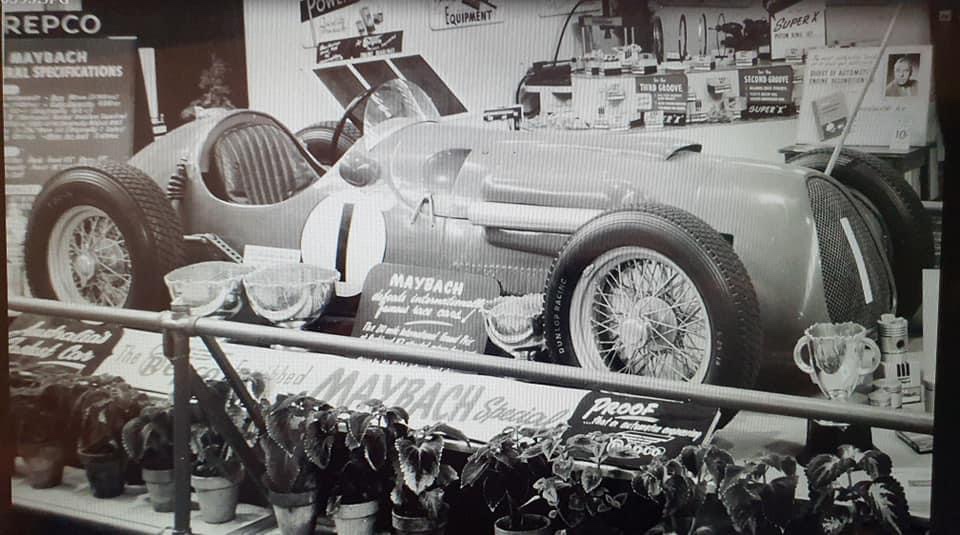

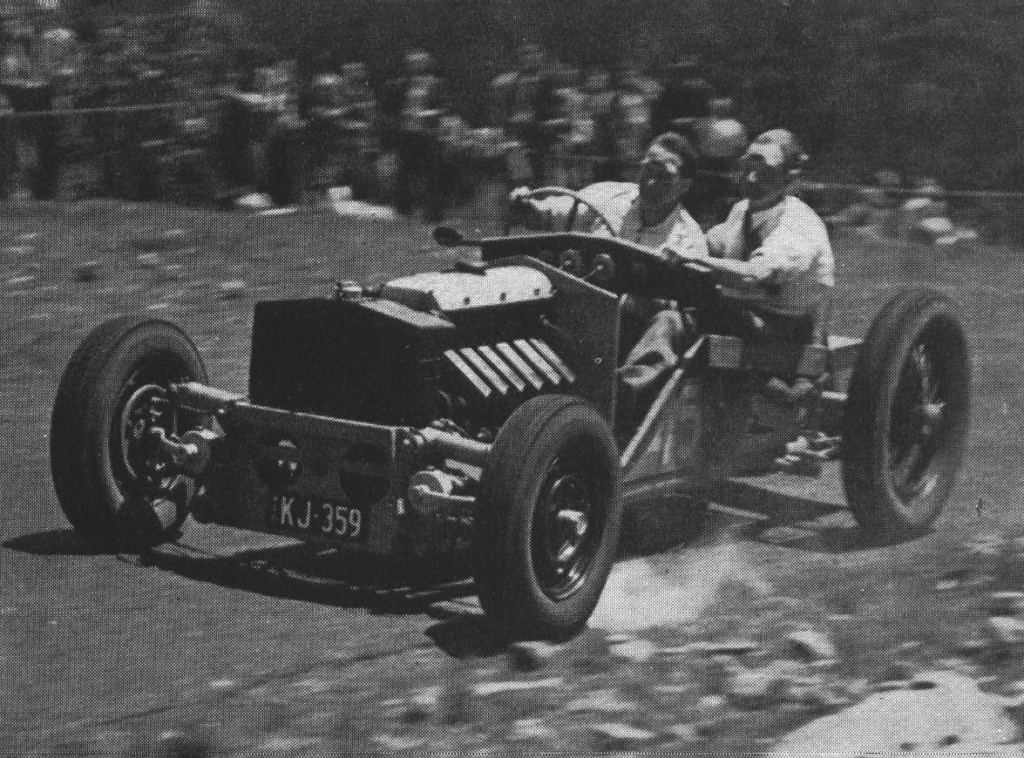

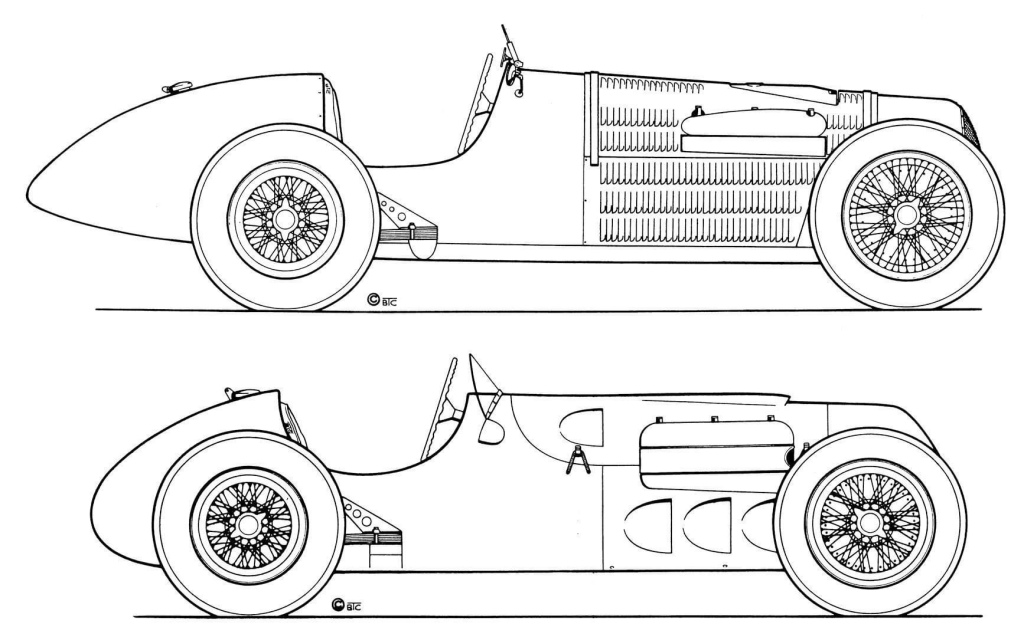

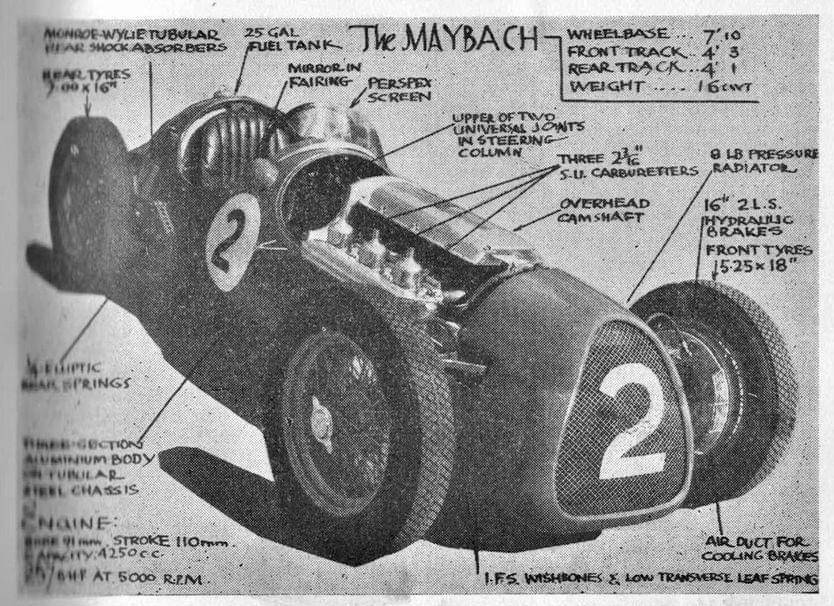

They are the Charlie Dean Maybach period from the early to late fifties- racing Maybach’s 1 – 4 with Stan Jones as driver. Then the Repco Hi-Power head period- a program initiated by Dean with the head designed by Phil Irving. Whilst aimed at road use, these heads which sat atop Holden ‘Grey’ six-cylinder motors had huge racing take up.

The Coventry Climax phase was run by Frank Hallam from 1962 onwards when Jack sought assistance to prepare and supply parts for his 2.7 litre and later 2.5 litre FPF’s. Michael Gasking primarily built and tested the engines.

Then comes the RBE program initiated by Jack in 1963’ish, sponsored at Board level by Dave McGrath, CEO of Repco Ltd and Charlie Dean, by then a Repco Director. Bob Brown, a Repco Director was appointed by McGrath as Director of RBE Pty Ltd- the entity which built the motors with Frank Hallam as General Manager. Phil Irving and Norman Wilson were the Chief Engineers in 1965/6 and 1966-9 respectively.

The final phase was the Repco Holden F5000 era from 1969 to 1974 with Dean the Repco Director in charge of REDCO Pty Ltd. (Repco Engine Development Co) Malcolm Preston was General Manager/Engineering Chief…and in the words of the great Gomer Pyle ‘Surprise, Surprise, Surprise!’- Phil Irving returned as Chief Engineer.

Phil was ‘brought in from the cold’ by Charlie and Mal given Frank Hallam was out of ‘earshot’ at Repco Research in Scoresby, a long way from Maidstone! You can bet your left nut that Hallam would not have been a happy camper when that particular bit of news made its way to his part of the Repco Empire.

I may have laboured the point- which is that by the time of the RBE program Repco was a corporate with a racing culture and ethos- if not throughout all of the conglomerate at least embedded in part of it.

Click here for a feature article on the Repco-Holden F5000 program;

Repco Holden F5000 V8…

Repco Boardroom, St Kilda Road, Melbourne probably late 1965 L>R Bob Brown, Frank Hallam, Jack Brabham, Sir Charles ‘Dave’ McGrath, Ted Callinan and Charlie Dean – all but Hallam and Brabham were Repco Ltd Directors (Tate/Repco)

Building on that, the key planks of Repco motor-racing participation and success start with Charlie Dean, a racer to his core- Maybach car builder, AGP competitor and the rest.

But of course he wouldn’t have been able to run the Maybach program within Repco and develop a whole swag of engineers and a ‘racing culture’, especially within Repco Research in Sydney Road, Brunswick without Managing Director and later Chairman ‘Dave’ McGrath’s ongoing support of him- and later Jack in a very personal kind of way.

McGrath’s patronage of the various race programs went all the way through to his retirement from Repco.

Frank Hallam was a good choice as RBE General Manager- he marshalled the forces within the typically political nature of a large multi-national very well and managed the Coventry Climax program with Jack and other customers effectively.

The misgivings by some close observers of Repco about Hallam are the enormous over-reach in his engineering design claims generally and for RB620 in particular- at Phil Irving’s expense. Without ventilating that again, see here for my thoughts on the topic; https://primotipo.com/2017/04/21/repco-rb620-inside-story/

McGrath made the decision to give senior executive responsibility for the RBE program to Bob Brown, in part because the Coventry Climax project was run within Brown’s Repco division. It was Brown to whom Hallam reported and who in turn was accountable to the Repco Board. In some ways the more logical choice would have been Dean for all the obvious reasons, whereas Brown was not a racing enthusiast at all, quite the opposite in fact.

It seems to me what McGrath was after was the commercial objectivity Brown would bring to the table- success was far from assured at the outset after all, rather than Dean’s racing knowledge. Dean at the time was Director of another division of Repco. Brown would assess the corporate promotional value and engineering technological rub off of the race program far more objectively than Charlie would as a ‘died in the wool racing enthusiast’ perhaps. Upon reflection it was another astute management choice by McGrath, one of the outstanding Australian industrialists of his era.

I won’t chase the McGrath tangent but see here for the Australian Dictionary of Biography entry for Sir Charles McGrath; http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mcgrath-sir-charles-gullan-dave-15173

To those key people you can add those around the car in the Longford pitlane- Phil Irving, RB620’s designer, brought to the table by Dean, Brabham- ‘architect and instigator’ of the entire program and its lead driver, Roy Billington, BRO’s Chief Mechanic and Ron Tauranac, designer and constructor of Brabham cars. Lets not forget Denny Hulme as well in the second car.

The cast for 1967 changed a bit with Phil’s departure but for that first year the folks mentioned were both the project foundations and the ‘tip of the spear’ on the Grand Prix and other grids.

The BRO 1966 crew- Bob Ilich, Roy Billington, Hugh Absolom, John Muller, Cary Tayor, Denny Hulme, Jack Brabham, Ron Tauranac, John Judd and Phil Kerr. Car is a BT20 620

RB620-E2

2.5 litre

BRO

Used by Jack in BT19 in the two 1966 Tasman races at Sandown and Longford

As at July 1968 it was a mock up display engine

Rod ‘4 March 1969 620 3 litre E2 received from Mayne Nickless’

Engine fitted to BT19 when restored

1 January 1966 first race for a Repco Brabham Engines V8, South African GP East London. Jack is on pole in car #10 Brabham BT19 620 fitted with engine E3, winner Mike Spence is in the #1 Lotus 33 Climax with Denny’s #11 Brabham BT20/22 Climax FPF completing the front row. Car #12 is John Love’s ex-McLaren 1965 AGP winning Cooper T79 Climax (unattributed)

RB620-E3C

3 litre

BRO 1966.

This motor had slightly larger inlet valves, ports and throttle diameters compared with the 2.5 and gave 280 bhp @ 7500 rpm.

It was flown to England after 6 hours testing, fitted to BT19, tested at Goodwood briefly and then transported to South Africa for the non-championship GP at East London on 1 January 1966

BRO is ‘Brabham Racing Organisation’

MRD is ‘Motor Racing Developments Ltd’, a company owned by Jack and Ron Tauranac which built Brabham racing cars.

BRO was one of Jack’s businesses which raced the works cars.

It acquired the cars from MRD, hired drivers, entered races, prepared them, banked the prize money etc- initially it was owned entirely by Jack, and later, from about 1966 after Ron, quite reasonably chucked a wobbly, Tauranac also had an equity interest.

Don Halpin wrote that engines E1 and E2 were built at Richmond.

The move from the corner of Burnley and Doonside Streets (81 Burnley Street) Richmond to 87 Mitchell Street Maidstone…

Generally speaking moves of business premises tend to be to a location close by- employers more often than not do it that way to keep the team in the boat.

Whilst 14 kilometres is not too far the decision of Repco management to move the ‘sexy bit of Repco’ was a biggie in local terms as the shift was from Melbourne’s inner east of the Yarra to the not-so-inner west, then very much the ‘wrong side of the Yarra’ especially to those east of the river, which was most of the RBE employees at the time.

These days the West is much more gentrified with places like Williamstown, Seddon, Spotswood, Yarraville and Footscray attractive places to live (Williamstown always was top-shelf mind you). But Lordy, in the pre-Westgate Bridge days, which slowly started the transformation of the west, that was shocker of a commute.

For someone like Phil Irving, commuting from Warrandyte, then and now semi-rural Melbourne outer east it was a ‘cut lunch and camel ride’ away. In fact, dealing with that daily drive and Phil’s flexible working hours was a big factor in the melt-down of the relationship between Contractor Irving and Company Man Hallam.

Stories abound of Phil’s nocturnal hours and his raids on the biscuit barrel overnight leaving the cupboard bare.

Tait, ‘All of Phil’s Repco Brabham drawings (he drafted all of RB620, Tait has sighted every drawing made and signed by Phil) and those of our other designers are now preserved in the RMIT University Design Archives’ in Melbourne.’

Wolfe recalls ‘When I joined in late 1965 the project had just arrived at Maidstone. The General Manager was Frank Hallam. In the drawing office, the Chief Engineer was Phil Irving, he was assisted by a young guy named Howard Ring. All the drawings from part number 620-001 (crankshaft) were in that office.

Peter Holinger was the Production Engineer, the Production Superintendent/Factory Manger was Kevin Davies. We also had a Commercial Manager, Stan Johnson who came and went’.

‘Around this time Michael Gasking also transferred from the Richmond Laboratory- he was Chief of Engine Assembly and Testing. Nigel Tait helped him as did Graeme Bartils who was a qualified mechanic helping assemble the engines at Maidstone. All the engines were tested at Richmond until we got to the second stage of our own test house’ recalled Rodway.

Tait ‘Mike Gasking was mostly at Richmond because we didn’t move the Heenan and Froude GB4 dyno until late in 1966 and all of the engine running for RB was on the GB4 until late 1966 by which time the new cells were ready (see snippet later) and the new G49EH H & F dyno was bought.’

On the machine tools as leading hand was David Nash and John Mepstead who was a great all rounder and about five other guys. Even the old capstan lathe on which I first made the RB engine studs for E4 onwards had been set up at Maidstone in late 1965.’

Equipe Repco Brabham out the front of the RBE Works at 87 Mitchell Street, Maidstone during the 1967 Tasman rounds. Tow cars are HR Holden Panel Vans as we call such things in Oz! (E Young)

Tait remembers the move ‘The plant there, in fact the whole site had been bought by Repco about a year before, it basically housed the old ACL companies (the land and buildings had been acquired by Repco as part of acquiring the businesses themselves).

The one we used for Repco Brabham was the old Glacier factory, on the corner was the Perfect Circle factory. There were still hundreds of bearings stocked there.’ Wolfe remembers ‘I transferred from Replacement Parts (another Repco subsidiary) and when I arrived Kevin Davies took me next door to watch them making piston rings and the girls production line packing them.

‘As I recall, the move over from Richmond to Maidstone took place over 1966 with new machinery coming in, and as a Cadet Engineer my bit was to make shadow boards for the new machines. I was never officially at Maidstone apart from the shadow board work and helping Mike Gasking with assembly of some of the early engines which he and I then ran back at Richmond’ Nigel’s ever sharp brain recalls.

Amongst all of the parts moved was a stock of Coventry Climax 2.5 and 2.7 FPF components which Mepstead recalls moving in his van over the 1965-1966 Christmas period to Maidstone.

The Climax stock of parts was shifted from the east to the west of the Yarra and lasted all the way to 1970 when Malcolm Preston was still doing ‘mailers’ to get rid of unwanted stock in the formative Redco F5000 era. Amusing amongst Rodway’s collection is the customer list complete with the ‘lousy payers to whom credit was not to be extended’. I shall protect the names of the innocent.

Wolfe recalls there were 12 un-machined Climax blocks (provided by CC in the UK, not cast in Australia as some sources would have it- which were progressively sold when fully machined) as well as a good stock of pistons and rings, Wolfe made Climax main bearing studs on the old Herbert capstan lathe- no Coventry Climax engines were bench tested in Maidstone- that work had all been done in Richmond.

Jack in the BT17 Repco 620 4.4 at Oulton Park in 1966, Brabham’s only race in the car (N Tait)

RB620-E4

4.3 litre

BRO 1966.

Sent to the UK at short notice and fitted to the Brabham BT17 sportscar, the only Group 7 car MRD ever made- a car acquired by Nigel Tait in mid 2018.

Hallam instructed Irving to build this engine, which had not been scheduled and interrupted the F1 build program, causing ructions internally- in fact the engine was a 3 litre F1 unit, which was pulled down and rebuilt to 4.3 litres in capacity.

Producing circa 350 bhp, the motor had considerable blow-by, which was addressed with a dose of ‘Bon Ami’ washing powder down the inlet trumpets, to bed in the rings.

Irving in his autobiography records that his suggestion of a teaspoon of Bon Ami sprinkled into the air-intake had been interpreted as a teaspoon full into each cylinder! The engine, as a result, ‘had to be dismantled to get rid of the abrasive, which had smoothed up the bores nicely but had enlarged them by about six-thou. The engine was running again by Sunday evening and was duly crated and sent off by air…’ Irving wrote.

It was ironic that Nigel would buy the car whose 620 engine he had worked on in 1966 five decades later albeit then fitted with a 5 litre 740 V8 the second owner acquired with the car when sold by Brabham.

The blow-by was caused by distortion of the dry sleeves which was solved by the adoption of wet sleeves in the 700 and 800 series blocks.

April 1966

Returned to RBE and dismantled as at July 1968. Scrapped

(M Gasking)

The document above is Mike Gasking’s RB620 reference note to check the timing of the engines before testing it. Gold, isn’t it!

RB620-E5A

3 litre

BRO 1966

Second 3 litre engine used by Denny in the French GP

Ongoing development of the 3 litre 620 V8’s yielded 310 bhp @ 7500 rpm and 260 bhp from 6000 to 8000 rpm

E5 had one new block

RB620-E6B

3 litre

BRO 1966

E6 rebuilt with 3 new blocks

July 1968 ‘Now in South Africa’- Luki Botha ex- BRO

E6 RB620 dyno plots by Nigel Tait

RB620-E7A

3 litre

BRO 1966

Dyno tested on 20 and 27 June, 12th (Wade Climax 133 cam) , 14th ,19th (133 cam) and 27th (after second rebuild) July 1966

(G Bartils- Wolfe)

Given the pages of details on this motor, it appears that it was used as a development engine at RBE at least until the dates recorded above.

E7 rebuilt with 1 new block

Dave Charlton, South Africa ex-BRO

(G Bartils- Wolfe)

Repco Brabham RB620 3 litre (Repco)

The RB620 first coughed into life in March 1965 in the Doonside Street, Richmond Engine Lab and was still winning races in Australia into the seventies- it had a nice long life.

In all of the bullshit about who gets credit for this motor, having listened to lots of different people and read all manner of material Brabham is its conceptual designer. His outline to the Repco board was a simple race engine comprising the Olds F85 block, SOHC, two-valve heads and fuel injection.

The detail designer inclusive of ALL of the drawings was Phil Irving, with Brabham ‘keeping an eye over his shoulder’ during those late night sessions in the UK at Phil’s flat in early 1965 with the Repco design team finessing ports, valve sizes and bibs and bobs after Phil was given the flick by Frank Hallam. Or resigned, depending upon the account.

Hallam marshalled the forces of the clever artisans of Maidstone to build it- a considerable contribution in itself.

Developmental issues in use involved various elements and solutions.

The ‘Fordson Major’ tractor oil pump gears were machined from steel after the 1966 Sandown Tasman failure.

The Lucas fuel distributor ‘was originally driven by the portside camshaft at the rear. After the South African disaster (in fact after Sandown) where the belt failed while the engine was winning its first GP Phil moved the distributor into the front of the valley and it was driven by a common shaft with the Bosch ignition distributor…The Lucas petrol injection is referred to as a fuel distributor rather than a ‘metering unit’ in that it does not pump fuel to each injector. The fuel is supplied by a 100 psi (‘fuel bomb’) pump to the fuel distributor which meters the fuel to each injector’ wrote Rodway.

Wolfe ‘We started fitting stronger dry liners after, i think, Monaco as a liner split. Jack sent the engine back to Maidstone and we bored the cracked liner out and found a cavity under the crack. (The liners in the 600 blocks were cast into the aluminium by Olsmobile) From then on we just shrunk the liners in, after boring out the cast in liners we heated the blocks, took the liners out of the dry ice and dropped them in. The 700 and 800 blocks had wet liners.’

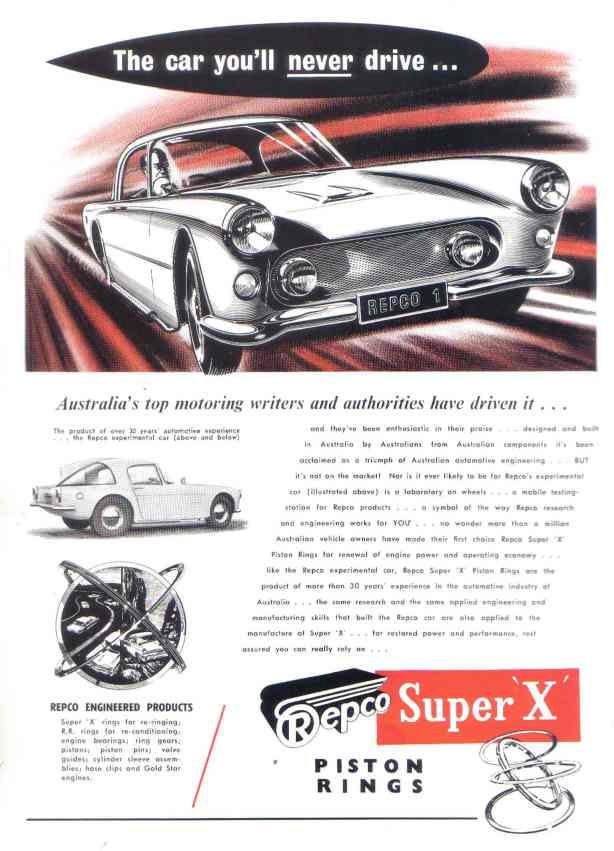

The newspaper advertisement above is a very early one, the car shown is BT19 with ‘E2’ 2.5 fitted whilst in Australia early in 1966. Repco have no race wins to promote just yet, but they would come soon enough.

RB620-E8

3 litre

BRO 1966

Assembly on 23 June 1966

July 1968 ‘Now in Switzerland’ – to Guy Ligier (France) ex-BRO then to Silvio Moser?

(G Bartils- Wolfe)

See Michael Gasking’s dyno test data sheet below on E8-306 bhp @ 7750 rpm in November 1966- amazing to think Jack won the World Title with a smidge under 300 bhp that year.

(Repco Collection)

RB620-E9

4.4 litre

Rod ‘Supplied to Bob Jane after rebuild on 3 November 1967’

July 1968 At RBE dismantled. Scrapped

RB620-E10

4.4 litre

Bob Jane- fitted to Jane’s Elfin 400 in late 1966- first raced in the 1967 Tasman Rounds, this engine was the first customer motor sold by RBE as against works engines used by Brabham

Bob Jane, Elfin 400 Repco ‘620’ 4.4 litre, Lakeside Tasman meeting 1967 (W Byers)

Bob Jane rebuilt and sold the 400 to Victorian Ken Hastings after Bevan Gibson’s tragic Easter 1969 Bathurst death in the car but sans engine.

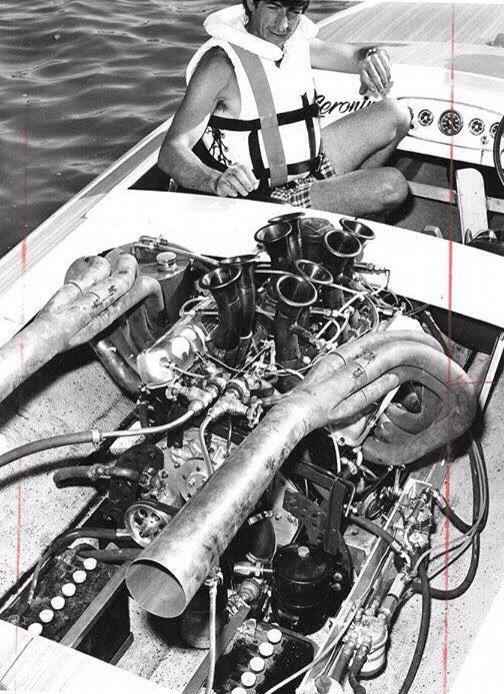

M Richardson acquired the engine for a boat

Click here for an article on the Jane 400; https://primotipo.com/2018/04/06/belle-of-the-ball/

Jack Brabham and Commerce…

Jack was a tough nut, he was in the business of motor racing, not motor sport, after all.

Repco’s spare parts business was enhanced in that Jack sold cars fitted with engines which in theory at least, were on loan to him as part of his sponsorship arrangements with Repco…

Wolfe ‘We never ever received a going engine back from Jack. Not even the Indy engines. Jack sold anything he could get. In 1967 five Repco Brabham engines started the South African Grand Prix- Jack and Denny were the only ones with our (RBE) engines. The others were Jack’s deals’- that is engines fitted to cars sold by Jack to other drivers.

‘Don’t get me wrong, Repco didn’t worry. I had to write up a (internal) sales docket for each engine sent to the UK but there was no payment made, we were sponsoring BRO. But Jack was a lethal businessman and i don’t blame him…It was in his interests to not be specific about which engine is which (in terms of keeping track of individual engines)

‘…he sent back the remains of BT19 to Australia, all that there was, was a very dilapidated chassis…a very clever restorer called Jim Shepherd did a brilliant job…i don’t know who paid the bill but it wouldn’t have been Jack. Repco purchased the BT19 from Jack but every time i ever talked to him at various Adelaide GP’s and wherever since he kept saying he owned it.’

Charles McGrath and ‘Deals on Wheels’ Jack Brabham after their 1966 successes (Repco)

Frank Matich picked up the theme in a September 2012 MotorSport interview with Australian journalist Michael Stahl.

‘Matich says his 1964 season was handicapped by the absence of his best Climax engine and the forged rods and pistons he’d had made in the US. Repco was proposing to build Climaxes under licence, Brabham had suggested they borrow Matich’s for development.

He was again leading at the next round, Lakeside (having started from pole at Warwick Farm) when his cobbled-together Climax blew up. “Denny Hulme came over and said, “Frank we’ve got the same bits, I worry we might have the same problems”. I said “What do you mean the same bits?”, he said, “Well I’ve got your pistons and rods”.

“And this was what Jack did a lot. He was f**kin’ ruthless. He was an old villain! He’d look you in the eye and just laugh at you. You’d get the shits with him, but there was no point, he’d just do it to you the next time. That’s how he won”.

‘Earlier this year (2012), Brabham was named one of Australia’s living treasures. Matich doesn’t dispute that for an instant’.

“Well he is a national treasure! Mate, I admire the bloke. Anything I say that’s critical, please don’t take it the wrong way. I’ve been bitten by him, but I just put it down to being a mug. I knew what he was like, because i’d been told by Bruce and others. But we’ve always been friendly. We never had cross words” Frank concluded.

Let it be said that FM was not exactly a ‘shrinking violet’ himself!

Name a World Champion who wasn’t or isn’t a tough nut! Jack could charm the birds from the trees when required but he was a hardened professional who understood what it took to win and his market worth from his earliest pro-Speedway years in the late forties.

Without doubt every dollar invested in BRO by Repco was returned tenfold by Jack and the team.

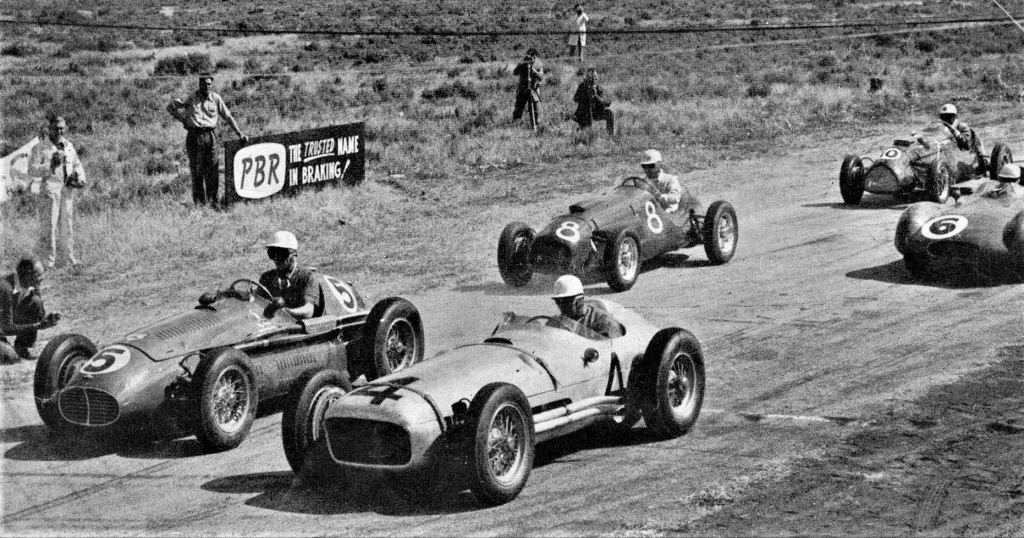

Jack Brabham customer deals? Team Gunston launch prior to the 1967 Rhodesian BP at Bulawayo, Sam Tingle and John Love, both Repco 620 powered. #4 Tingle’s LDS Repco built by Louis Douglas Serrier and #1 Brabham BT11 Repco ‘with Cooper suspension’ (wheels.24.co.za)

RBE Dyno House…

The test house, ‘down the back’ of the Mitchell Street site was ‘Designed by the Repco Architect and Ross Kirkham who was the Manager of the Engine Lab (in Richmond) and by the way a brilliant engineer’ wrote Nigel Tait.

‘The concept was that the exhaust from the engine went into a space in the walls which was cleverly attenuated and there was no back pressure or need for silencers.’

‘Ross, no longer with us sadly, was one of the nine in the Automotive Components Ltd buyout in 1986 and for quite some years he was the Manager of the ACL Bearing Company in Launceston (Tasmania)’.

RB test house at Maidstone- first stage, engine testing continued at Richmond until the second stage of the building was completed (R Wolfe)

Wolfe recalls ‘a tape recording of Mike and Barty testing the ’66 German GP engine..’ (where is that Rod?) ‘the second test house was built a fair bit later and the hydraulic dyno added’.

The conditions in Doonside Street Engine Lab in Richmond were altogether more Dickensian with Rod’s favourite photo the one below of Mike Gasking on the dyno and Nigel Tait manning the throttle with his wedding tackle rather too close to the action for me- neither protected by a safety wall.

The Dyno was ‘actually in a temporary tin shed 100 metres down Doonside Street with no acoustic sound absorbing on walls or roof. And the tube from the exhausts went straight out into the open air. The noise was so great that Vickers Ruwolt who had their factory across the road said the cracks in their wall was caused by us! Quite likely’.

‘The front entrance to our building was known internally as “Lavatory Lane” since that’s where they were’ recalled Tait. Wolfe’s response- ‘World Championship Winning F1 engine built in a Tin shed on Lavatory Lane, Melbourne, Australia’…

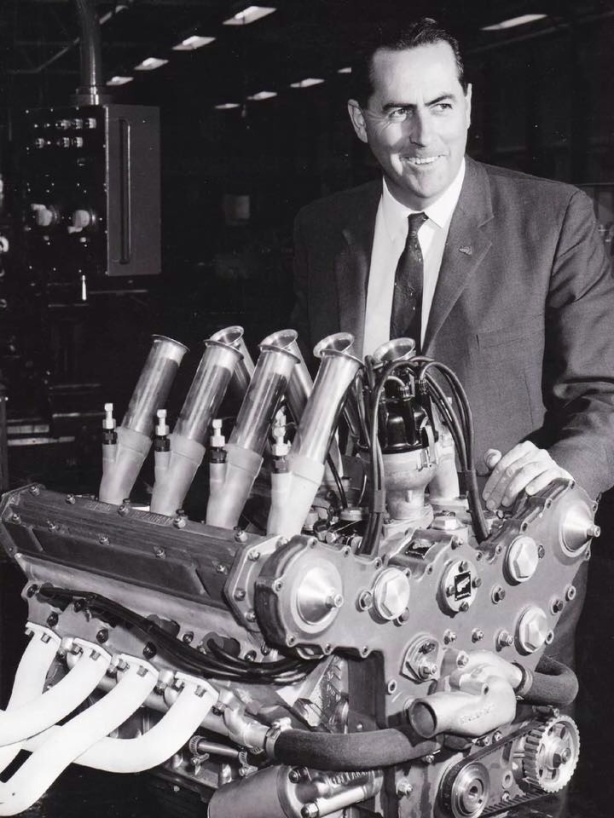

(Repco)

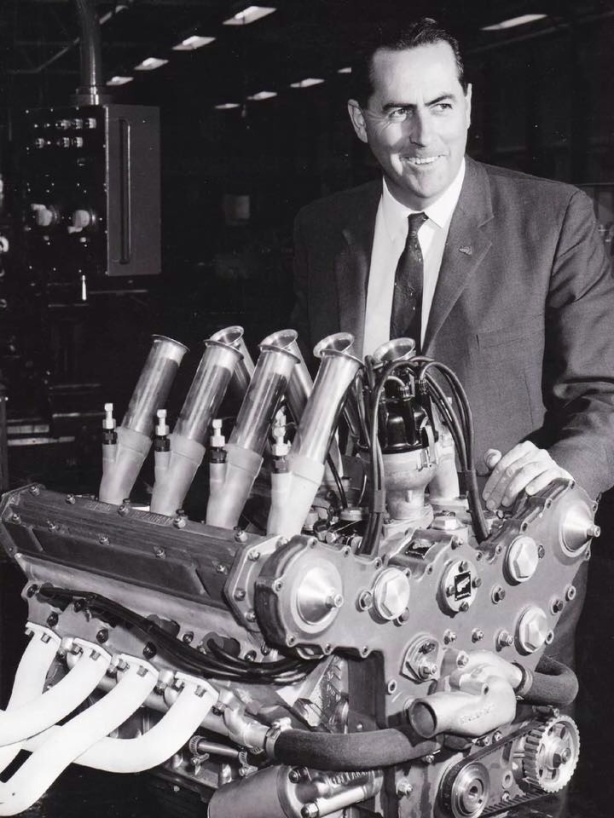

Mike Gasking was almost the Repco ‘in house model’, he is in so many of the PR shots in part because it was his role to assemble and test the engines but no doubt also due to his youthful good looks!

Gasking recalls Ron MacLaine and Peter Telford from Repco Head Office at 618 St Kilda Road as the pair who contracted David Holmes as the official Repco photographer across the group.

‘We were not very good at publicity with many of the dyno shots done at very short notice, so i always had to dress well’.

(Repco)

‘The noise in the dyno room was unbelievable and frightened most everybody. You can see with the 4.2 Indy engine percolating very well (at Maidstone above), everybody had left the room except the photographer and me. Then i would work the engine as you can see, my photo says it was around 7000 rpm. I have the Db reading somewhere.’

‘To think we ran fifth at Indy (Revson in 1969) was fantastic. Norman Wilson and Don Halpin were there, i only did the dyno work and final assembly- notice no guards or other protection.

I can’t recall ever an angine failure on the Dyno. We ran the 2.5 and 3 litre in excess of 9000 rpm or a bit more but did not necessarily tell Jack or Denny about this!’ quipped Michael.

Australian engine builder/race engineer/driver mentor and allround guru Peter Molloy recalls it as ‘spooky with the controls in the room, years back i was in THE room, with Mike doing (John) Harvey’s 2.5 and was glad to get out’.

‘I have seen a flywheel ring gear split and spear the wall separating Merv’s (Waggott) office from the Dyno Room at Waggott Engineering (in Greenacre, Sydney). It had the effect of wanting to hitch your pants up!’

1967

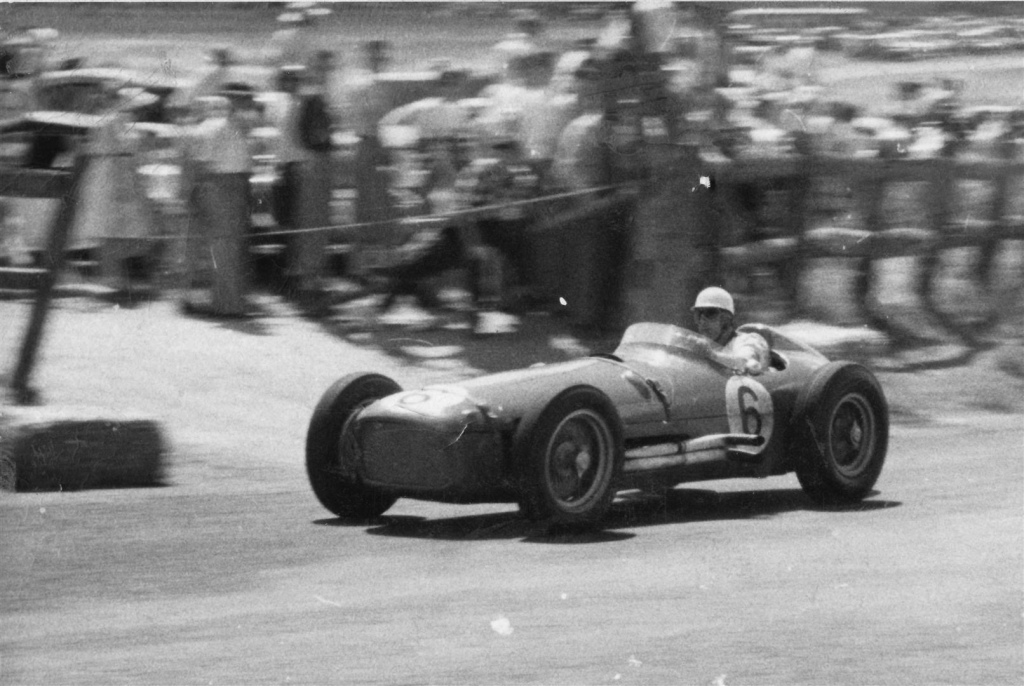

Denny, BT24 ‘740’ Mosport 1967

The ‘sheer economy’ of Ron’s 1967 BT24’s always blows me away.

One of my favourite GP cars had just enough of everything- power, torque, chuck-ability and forgiving handling, it was as aerodynamically efficient as anything out there at the time and more reliable than other machines up front.

The only thing it didn’t have much of was weight…Oh, it didn’t use much fuel either.

RB640-E11C

2.5 litre

David McKay- fitted to McKay’s Scuderia Veloce ex-works Jack Brabham 1967 Tasman car BT23A raced by Greg Cusack, Phil West and others

Rod ‘8 November 1967 E11B sent out for display (no record of return)’

Rod ‘3 January build up’ and 9 January 1968 E11C dyno 265 bhp’

Rebuilt with 700 Series block, described as 740 in July 1968

2.5 litre 640 Series V8’s gave around 277 bhp and were 6 Kg lighter than the preceding 620 2.5

Rod’s diary notes delivery, after a rebuild, to SV on 16 June 1969

I Harvey for a boat- ex-McKay

The engine has turned full circle- fitted to the BT23A owned by the National Automotive Museum as an RB740 E11C 2.5 litre

RB640-E12

2.5 litre

July 1968 At RBE dismantled. Scrapped

RBE/BRO had a full-on attack on the 1967 Tasman- two cars with Jack racing BT23A and Denny a BT22. Am guessing this was one of the float of engines used that summer

Rebuilt with 700 Series block, described as 740 in July 1968

One of the 1967 Tasman ‘640’ 2.5 Brabham Repco’s in the Levin paddock (M Fistonic)

Denny not best pleased with his Brabham BT22 ‘640’ 2.5 at Wigram in 1967 (Classic Auto News)

RB640-E13

2.5 litre

The Repco lists I have do not mention it but this engine was first fitted to the RC Phillips owned Brabham F2 BT14 raced by John Harvey in 1967.

The car, prepared by Peter Molloy when sorted was quick, inclusive of a ‘Diamond Trophy’ win at Oran Park later in the year.

When Spencer Martin retired from racing, having won two Gold Stars in 1966 and 1967 Jane hired Harvey to replace him- and acquired the BT14 with this engine.

For whatever reason, Jane’s team removed the motor and fitted it to Jane’s Brabham BT11A- rather than race the BT14 which had its teething problems behind it.

The BT14 was sold.

John Harvey raced BT11A in the 1968 Australian Tasman rounds.

E13 was then fitted to Jane’s ex-Brabham 1968 Tasman car – the Brabham BT23E which was raced by Harvey from 1968-1970.

Rod ‘3 January On dyno 259 bhp’

Rod ‘9 January 1968 E13B delivered to Bob Jane’

Rebuilt with 700 Series block, described as 740 in July 1968

To Peter Simms and fitted to BT23A in the modern era. Is now the spare engine of BT23A in the hands of the National Automotive Museum as RB740 E13B 2.5 litre (with E11C fitted to the car)

For the sake of completeness BT23E was also fitted with RB830 V8’s later in its life- the two 830’s were ex-Brabham BT31 1969 Tasman car (Sandown Tasman and Bathurst Gold Star). Rodway Wolfe recalls being instructed to deliver/allow the collection of these engines by Bob Jane Racing free of charge

RB40-E14

2.5 litre

July 1968 ‘Never completed’- described as 740- rebuilt or built again with 700 Series block

RB640-E15B

2.5 litre

July 1968 ‘Block only- at RBE’- described as 740

Rod 4 February 1969 ‘E15 returned for overhaul from Geoghegan’

17 June 1969 ‘started block changeover’- Wolfe diary

Used by John McCormack in his Elfin 600C- replacing the ex-Brabham BT4 Coventry Climax FPF first fitted to that chassis, in 1970

Then to Bob Wright for his Tasma (nee-Wren) Repco in Tasmania

RB640-E16

2.5 litre

Fitted to Leo Geoghegan’s ex-works Clark Lotus 39 Coventry Climax FPF 1966 Tasman car

Described as 740 in July 1968

Engine adapted beautifully into this chassis by John Sheppard and Bob Britton creating one of the prettiest of all sixties open-wheelers. An iconic car in Australia- and still here restored, sadly in my view, in Coventry Climax form

For the sake of completeness the Lotus 39 was also fitted with RB730- Preston says E16 was fitted with 30 Series heads- so at that stage is a 730

Later the 39 was fitted with an RB830 V8 in 1969/1970- perhaps this engine with 800 block?

Rod ‘Leo Geoghegan’s engine returned to the factory after bearing failure on 6 January 1969’. ‘8 January Geoghegan engine E16C on dyno’

Mark Beasy advises he has E16 640 Series- ‘with a hole in it! Would like to get the rest of the castings and turn it into a coffee table one day’ !

E16 730 was fitted to the Rennmax BMW sportscar circa 1971. Doug McArthur acquired the engine from Leo Geoghegan after Leo sold the Lotus 39- the Rennmax Repco is still fitted with the engine all these years later, I think its 3 litres in capacity now and owned in 2019 by Jay Bondini in Melbourne.

Click here for a feature article about the Clark/Geoghegan Lotus 39 Climax/Repco;

Jim Clark and Leo Geoghegan’s Lotus 39…

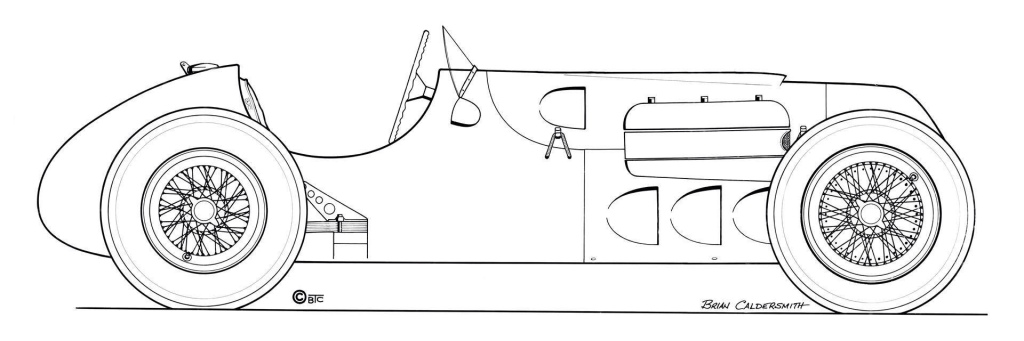

Repco Brabham RB740 (Repco)

Norman Wilson led the team which designed ‘740’, a masterful extension of the original 620 but with a bespoke block cast by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation at Fishermans Bend in Melbourne.

It was designed in such a way that the 20 Series heads, front case etc bolted to the new block thereby allowing the upgrade of the original motor cost-effectively.

Use of the ’40 Series’ exhaust between the Vee design was dictated by Tauranac or Tauranac and Brabham rather than the ’30 Series’ which, whilst designed at the time, came later in a production sense when twinned with 700 or 800 block to create the ultimate Tasman 2.5 engines.

‘The redline was 8200 rpm or as Jack said 8800 at a pinch!’ quipped BT24 owner Brian Wilson.

Cary Taylor, Bob Ilich, John Muller and Roy Billington in 1967 (Repco)

Brian Wilson ‘The car above is Brabham BT24-1 (a car he owned and raced for some years) A more common sight at GP’s was the cam-covers off (than the view above). Wear on the cams was an issue with the 740 engines. Peter Molloy fixed it by cutting microscopic holes in the lower section of the cam lobes’.

Rod Wolfe ‘It was not a problem on the 3 litre 40 Series (740), may have been on the 2.5 engines, but not enough for us to worry about it. Denny won in 1967 with our standard 740 Series. On the quad-cam (860) it sure was, it’s what destroyed our chances in 1968.’

‘Mike Costin’s ran cast Iron cams with steel buckets in the Ford Cosworth FVA after they had problems. We ran steel cams and steel buckets in our FVA (860) engines. I reckon that’s why we had collapsed cam buckets. Remember Phil (Irving) specified cast iron cams in our early engines’.

We will come back to the problems with 860 a little further on in this article.

RB740-E17

3 litre

BRO 1967

740 Series 3 litre engines developed around 350 bhp @ 8400 rpm

RB740-E18

3 litre

BRO 1967

Nigel Tait advises Alan Hamilton’s Tiga hillclimber has E18-740 fitted to it. Before that the motor was fitted to Roger Harrison’s Elfin 600C hillclimb car- the Tiga succeeded it.

Nigel has a spare block which is E18A- ‘My E18A has had a rod through the side but is welded up and renumbered’.

RB740-E19

3 litre

BRO 1967

Brian Wilson communicated that ‘The 740 engine in BT24-1 was E19. This engine was in the car when Basil van Rooyen got it from Jack in South Africa. Still in it when we had it. Amazing. The engine in BT24-1 now has no number. We built it up from scratch here as a spare.’

‘Jochen apparently drove the spare BT24 (BT24-3) a few times early in 1968 (he did, in South Africa and Monaco- whilst Jack assessed the 860 as ‘race ready’ and Dan Gurney raced it at Zandvoort as a third BRO entry) It actually finished some races unlike the RB860 engine BT26’s. The spare BT24 is the car which ended up in Switzerland looking a bit like a Lotus 49 and with a DFV. It was being restored in that form I last heard’.

(N Tait)

RB740-E? (BR 740/127E RAC)

Nigel Tait recently acquired Brabham BT17, ‘the engine number is ‘BR 740/127E RAC’, clearly not stamped by us at Repco.

Rod Wolfe observed ‘Is it possible that it had to be officially stamped for a particular race event, eg Healey ran a 740 3 litre in the Le Mans 24 Hour. In the US the Indy car guys had some strict rules.

When Jack arrived at Indy (in 1968) we got an urgent request for money to be paid before we could run ‘Repco’ on the side of the car. Also we had the latest Magnaflux crack-tester in Maidstone but for Indy all the engine internals had to have certificates from a registered aircraft crack-tester company…’

RB740-E20

3 litre

BRO 1967

RB620-E21

July 1968 ‘At RBE dismantled’.

Scrapped – block South Africa

RB620-E22

4.4 litre

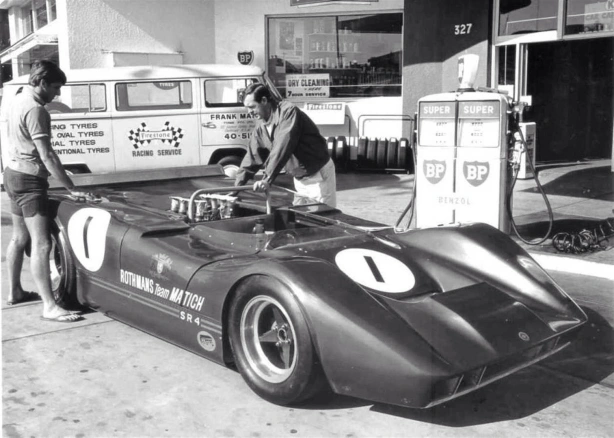

In production as at 30 June 1967 for Frank Matich who raced two Matich SR3 sportscars in most of the 1967 Can-Am Championship.

He then raced one of the cars (having sold another in the US) back in Australia giving Chris Amon a comprehensive belting in the ex-works Scuderia Veloce Ferrari 350 Can-Am in the sportscar supporting events which were part of the Australian 1968 Tasman rounds.

There are plenty of details about their tussles that summer in this feature on the Ferrari P4/350 Can-Am;

Ferrari P4/Can Am 350 #0858…

Matich, Matich SR3 Repco 620/720 4.4 at Calder, late 1968 (unattributed)

This engine was sold by Matich to Bob Jane.

Janey found a great home for it in creating one of Australia’s most iconic sports-sedans, the John Sheppard built Holden Torana GTR-XU1 Repco 620 4.4, the engine bay of which is shown above.

Sheppo is well advanced with a recreation of this car, it will be a joy to behold. Elfin Historic Centre owner Bill Hemming has the Elfin 400- it will be intriguing to know the engine number of Bill’s engine and the numbers of John’s ‘cache’ of Repco V8’s!

John Harvey driven, Bob Jane owned Holden Torana GTR-XU1 Repco 620 4.4 at Wanneroo Park in 1971. John Sheppard’s attention to preparation detail in all of his cars ‘concours’ (R Hagarty)

Article here on Australian Sports Sedans including some information on the Sheppard/Jane Torana Repco;

‘Hey Charger’: McCormack’s Valiant Charger Repco…

RB740’SSS’-E23

3 litre

‘SSS’- Short Stroke Special experimental lightweight, magnesium 700 block. Aluminium liners, magnesium pistons, light 2.5 litre crankshaft and 5 litre head- 1.9 inch inlet and 1.6 inch exhaust valves

Preston writes ‘A 3 litre 740 Series engine E23 was rebuilt with a magnesium 800 series cylinder block and later scrapped’

RB620-E24

3 litre

Scrapped

RB720-E25

5 litre

Rod ‘2 January 1968 completed and despatched’ in preparation for the Tasman Series sportscar support races

To Bob Jane ex-Don O’Sullivan

RB730-E26 X ‘Experimental’

5 litre

Rod ’22 November 1967 Sent for Repco advertising in Adelaide’

Later built as 740 for Bob Jane and fitted to the McLaren M6B sporty

RB740-E27 X

5 litre

Nigel Tait ‘After much research i’m now pretty sure the 3 litre 740 engine in the Brabham BT24 raced by Jochen Rindt in early 1968 was E27 and if so it went into the XR37 Healey that competed in the 1970 Le Mans but had an electrical fault with only 20 minutes to go.’

‘Then subsequently in a Palliser hillclimb ( A Griffiths) car with numerous owners (including John Cussins?) until the car was wrecked and the engine, which had been enlarged to 4.2 litres ended up in the Brabham BT17 that I bought in from England in 2018- and now that it is apart its actually 4.4 litres not 4.2!’

RB840-E28 X

3 litre / 5 litre ? Aluminium block

‘Mock up parts used in E28’ Don Halpin

(M Bisset)

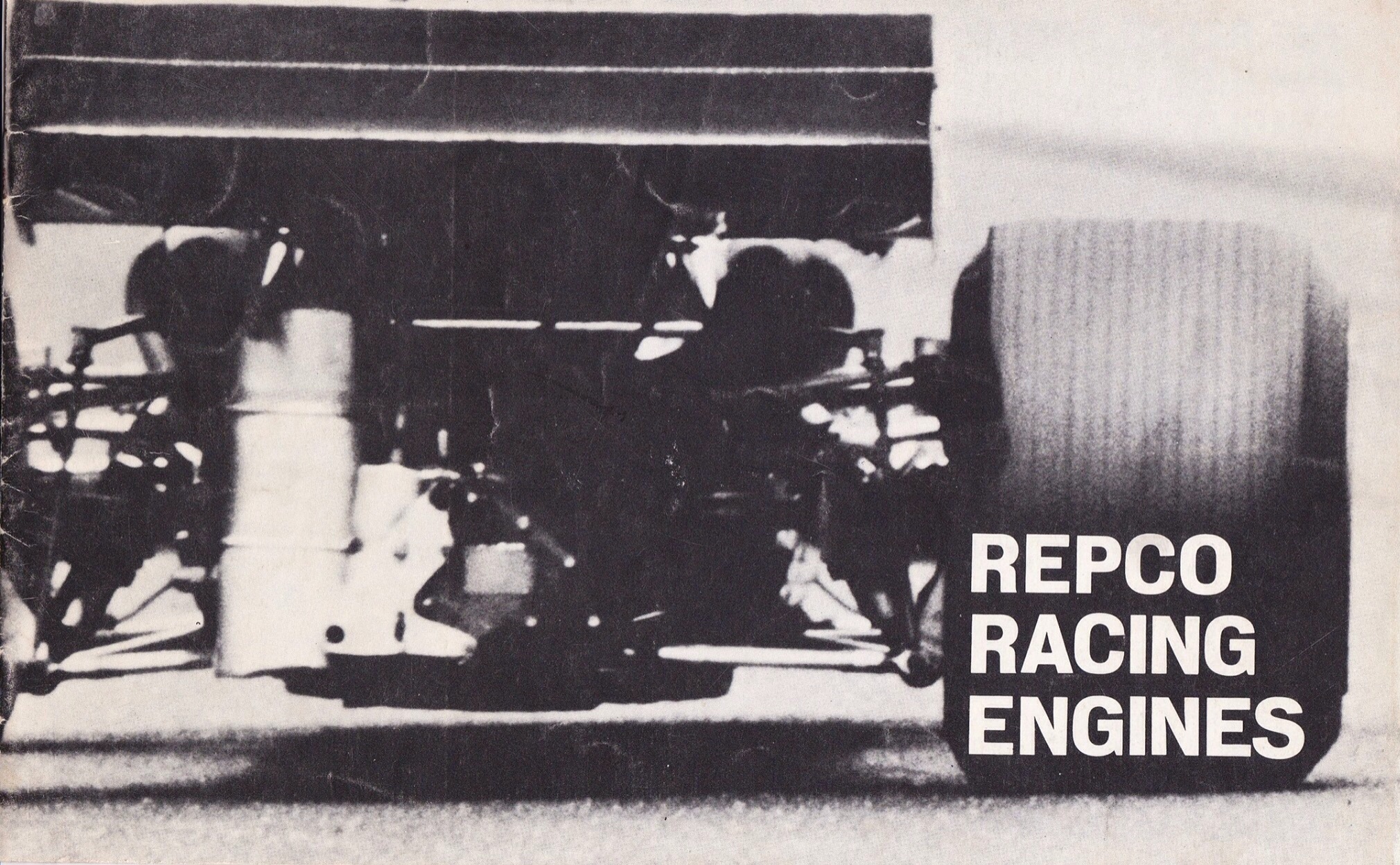

Repco and Innovation- The Diagonal Port 850 Series Engine Program…

So far I’ve not done features on the experimental 50 Series engine or the definitive, problematic 1968 quad-cam, gear driven, thirty-two valve Repco Brabham RB860 3 litre F1 engine- Repco’s DFV challenger if you will.

So we need to go into a bit of detail for the purposes of this engine-number exercise but not too much as I will come to each engine in due course in feature pieces.

Repco, Brabham and Tauranac read the play well for 1967, the mainly all new 740 did the job but only because the Ford Cosworth DFV- which won upon its debut at Zandvoort, was unreliable in its first year- without doubt the Lotus 49 Ford was the fastest car that year, driven as it was by Messrs Clark and Hill.

For 1968 ‘they all’ as far as I can see agreed they needed a more powerful engine given the number of DFV’s in circulation that year- Team Lotus, McLaren, Matra International and Rob Walker had the motors- the DFV won all but the French GP as it transpired, Ickx took that one in a Ferrari 312.

Frank Hallam, to his credit, pursued the innovative diagonal port path then also being blazed by BMW with their Apfelbeck 1.6 litre F2 engines.

Nigel Tait ‘The idea of the diagonal port quad cam engine is to obtain maximum airflow, hence power. With the inlet valves placed diagonally rather than side by side their theoretical diameter is greatest. But the opportunity for siamesing the ports is lost so this means there have to be inlets and exhausts on each side of the cylinder banks. Thus 16 inlets (and injectors) and 16 exhausts in total.’ See the photographs which illustrate the point.

Depending upon which account you believe the engine either gave about 400 bhp without development or not that much after a lot of development- circa 360 bhp.

The really important aspect here is the time taken to develop the 850, before, eventually the engine was put to one side.

RB850-E30

3 litre Radial- four valve engine bench tested but never installed in a car

360 bhp @ 7600 rpm with twin plugs and dual ignition to improve combustion

Rod ‘8 November 1967 Had the 750 cylinder heads vacuum impregnated (to fix porosity)

Rod ’13 January 1968 E30 start-up 365 bhp @ 9200 rpm’

Now owned by Nigel Tait

When I composed the photograph below at ‘Shifting Gear’ in 2015 I was juxtaposing the conservative BT19 and in particular its 620 engine with the ‘radical or edgy’ nature of 850.

I love the fact that Repco- Frank Hallam had a crack at gaining the ‘unfair advantage’ with this approach having two World Titles under their belts. His error of judgement, given that time was rapidly ticking, was to persevere with it long after his Chief Engineer, and others suggested it was time to move on.

Lets come to Chief Engineer Norman Wilson’s perspective in a moment.

(M Bisset)

In that lost time context Rod Wolfe’s 22 November 1967 diary note ‘Forwarded 850 Series mock-up to BRO’ is really interesting.

I mean in that if the shit had not already started to hit the fan in terms of the degree of difficulty Tauranac was going to have trying to adapt the engine with all of its induction and exhaust plumbing challenges to his spaceframe chassis for 1968- it well and truly would have when the engine mock up arrived at MRD.

With the notoriously conservative Tauranac and Brabham- very successfully so I might add, vehemently opposed to the 850, Hallam finally gave Norman Wilson and his team their head in developing the 860 motor.

But it was all too late.

Using the Tasman series in whole or part as a developmental exercise was a factor in the success of 620 and 740. Jack did only a limited 1968 Tasman campaign in a 740 2.5 engined Brabham BT23E with the 2.5 830 Series making its race debut in the final Tasman round at Sandown. 860 was not raced as it was not ready and not built in 2.5 litres in any event- there was not the time to do so.

RB860 is much maligned but should not be- the Rindt/Brabham BT26 860 combination were very fast in 1968 when the engine held together, which was not often and never for too long.

Lets not forget Jochen put the circa 400 bhp BT24 860 on pole at Rouen and Mosport- and started from grid two at Zandvoort and grid three at the Nürburgring- so the thing was not a slug, but reliability was woeful.

All of this was capable of being made good, in fact the motors fundamental problem was similar to that experienced by the DFV in 1967.

Norman Wilson ‘We discussed and explored a radial valve idea (for 1968) but we ended up using a combination of new ideas and old. What we finished with was the lower 800 Series blocks with twin overhead camshafts, four valves to the cylinder heads but without the radial valve idea’.

‘The radial valve thing didn’t work. Originally it was made so the gas went in and rotated. But this was really a blind spot Frank had. The gas went in and the heavier fractions of the gas got centrifuged to the outside’.

‘When you are lighting a fire in the combustion chamber you light the richest portion of the mixture first because that is the bit that will burn better faster. And with the spark plug in the centre we were igniting a very lean mixture. The problem was with the best engine we produced we had a 56 degrees ignition advance and so the piston is only half way up the cylinder at ignition. The pressure before it reaches top dead centre is just incredible and that’s negative work’.

‘Frank really wanted to do it, was absolutely desperate to do it. I think this is probably where the disagreements with Jack started with Frank. Frank was pushing this thing, it was stretching our resources more then it should have’.

‘I must be quite honest. I knew this would happen but I just never thought it would be as bad as it was. So we are into hindsight again. At the time you are flat out trying to get the 1968 engine built’.

‘I cobbled up some cylinder heads (the 50 Series) and went up to the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (in Fishermans Bend) to get them cast. We put two plugs in different positions away from the centre, but there were virtually no water spaces because of the complexity of the porting.’

‘We did what we could as a cobble up to try to get some dyno figures and see if we could ignite the mixture on the outside, the rich part, and get the thing to work. But it was quite obvious after talking to Jack about it that if we did get the thing to work it was pointless because Ron wouldn’t use it anyway (because of the installation difficulties in the chassis). I think this was the first sort of real breakdown between Frank and Jack.’

The 50 Series heads were never used in a car ‘In fact the engine (850 prototype) would have only done probably 15 – 20 dynamometer hours’ concluded Norman Wilson.

However, at the end of the unsuccessful 1968 season a confluence of events resulted in Repco Brabham’s withdrawal from F1. These were Brabham’s need for a competitive engine in 1969 with the DFV his preference, Repco Ltd having a new Managing Director when Charles McGrath stepped down in 1967 (he remained as part-time Chairman until 1980) and the fact that the company had largely achieved its brand building globally via the most cost effective three year raid on the World F1 Championship ever staged.

And all of this from an outfit that had not built an engine from scratch of any sort, let alone a race engine before 1965.

But lets for now leave the radial-valve 850, short block 2.5 litre 830 and 3 litre 860 and the 700 Series ‘long block’ Big Muvva 4.2, 4.8 and 5 litre 760 engines for the feature article they all deserve.

Back to the count, and the 860 engine shortly…

RB840- E31

2.5 litre

Bob Jane

RB840- E32

2.5 litre

Rod ’13 January 1968 magnesium block engine 264 bhp’ (Tasman engine)

Scrapped

Jochen Rindt in. Brabham BT24-3 at Monaco in 1968, perhaps fitted with E37 740?

RB740-E37

3 litre

BRO 1968

Rod ’11 April 1967 E37 3 litre 740 sent to BRO 330 bhp’

At the end of the 1967 season Jack and Denny’s BT24’s were sold with engines. Chassis BT24-3 was raced, as written earlier, by Jochen Rindt and once by Dan Gurney in earlier 1968- perhaps this was the engine fitted to that chassis?

(Repco)

The Engine assembly area at Maidstone…

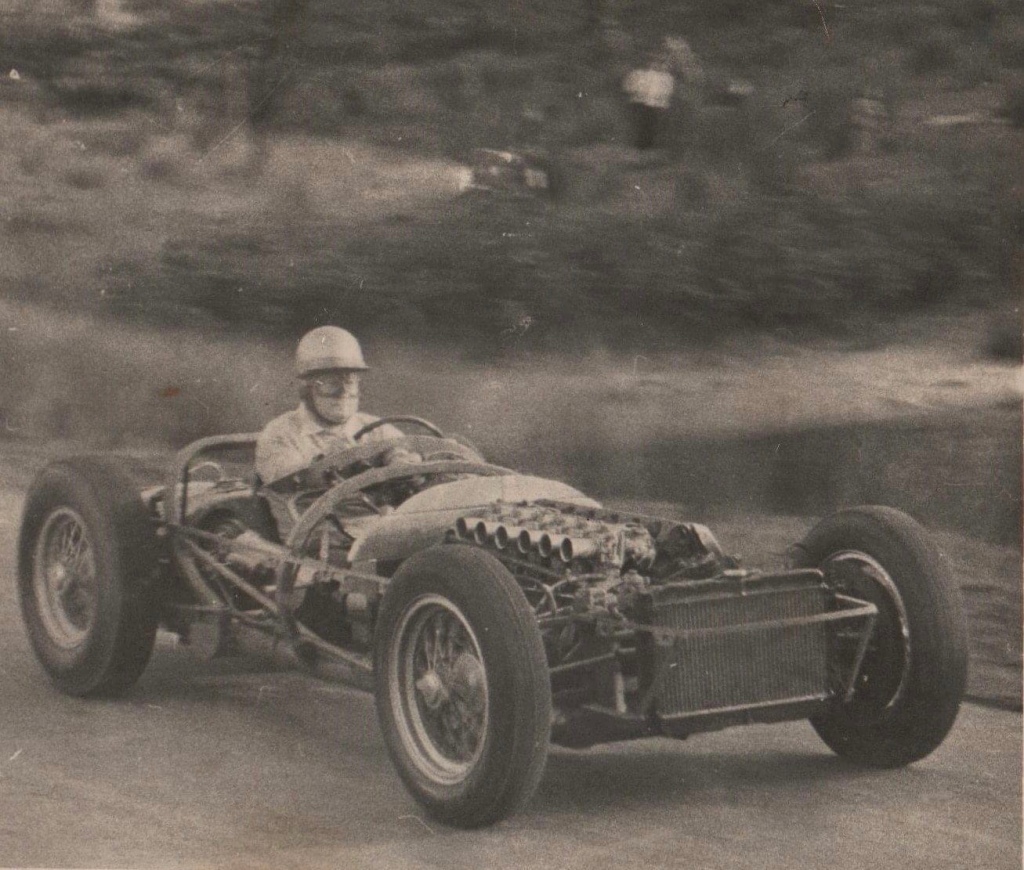

Rod Wolfe ‘From left to right- Michael Gasking, Don Halpin, Michael Clement aka ‘Rivella’ a Swiss ‘who didn’t know a word of English’, Graeme Bartils and John Mepstead.

Tait ‘That’s an interesting photo. The quad cam engines shown are almost certainly 4.2 Indy engines because they appear to be 700 Series blocks (as against the 3 litre F1 jobbies which used the short 800 Series block). Also they have Repco-Brabham cam covers- the 4.8 litre and 5 litre engine for Frank Matich (fitted to the SR4) had “Repco” only. One of these 4.2 litre engines is my spare for the Matich SR4. In the same photo is a 2.5 litre or 3 litre 40 Series engine with its central exhausts’.

In looking at these Maidstone factory photos its interesting to see the way RBE geared up to produce the engines in commercial quantities with reliable spare parts back-up.

That is, spares were available and when ordered would fit.

This is in no small part due to Frank Hallam’s well documented by him, and agreed by others, process of both using his Capex budget to buy modern machinery and his maintenance budgets to properly look after and update older equipment.

As a consequence engines of a particular type were the same rather than bespoke- in the latter case requiring a lot of hand fettling to assemble and run. I have in mind the problems Dan Gurney had with the Weslake V12’s in writing this sentence. Cosworth Engineering of course geared up with modern machinery to build an enormous number of production racing engines.

(Repco)

The engine mill shown above is perhaps the first such tape- controlled mill in the country.

Rod Wolfe recalls that ‘When we first set it up Peter Holinger (Production Engineer) made a tape for the reader- the thing that looks like a fridge on the right of the machine. He set the (mill) table up and started up the machine. With a loud hydraulic roar the table moved, north, south and west and then east and with a loud grunt everything stopped and silence.’

‘A big blue light came on the control panel. Me being my usual kid from the bush, I asked Pete what the blue light meant? In typical very dry Peter Holinger style he said “It means it didn’t bloody well understand what I asked it to do!” All the boys were standing around watching and old Phil Irving wandered up and said “Well its done its first job successfully, it has brought all production in the shop to a complete standstill!” They were wonderful days’.

Nigel Tait points out that ‘In the background against the wall are three crankshaft making machines which for some odd reason we bought from the BMC (Zetland) plant in Sydney. I doubt they were ever used’. Rodway ‘You are right Nigel, I never saw one go at all. They were set up with all the tools and everything for the BMC crankshafts, but I am not sure which models. I think Frank Hallam did have intentions of using them but the budget reductions later brought it to a halt. Bill Santuccione worked on getting them going for a time so he would know their story’.

Edward Newsome recalls the photograph below ‘I first started talking to Frank Hallam in 1965 while he was still at Russell Manufacturing (Richmond)…I sold the very first Numerically Controlled (CNC) machine tool in Australia to them. Left to right in the picture below are David Nash, John Acton, myself, Jack Brabham and Frank Hallam holding the timing case cover that I had programmed’.

‘It is a two axis Cincinatti Vertical Acramatic, they later bought a horizontal version too…the programs were done a line at a time on a Friden Flexoriter.’

(E Newsome)

(Repco)

Geoff Walker, above, around 1968/9 milling a quad-cam cylinder head. It could have been for an 860 engine of 3 litres or 760 of 4.2, 4.8 or 5 litres. Geoff is recalled as a very good programmer of the NC (numerically controlled) equipment and came from one of the machine tool companies.

1968

RB860-E33

3 litre

BRO 1968

RB740- E38

3 litre

Bob Jane (makes no sense- the capacity I mean for Tasman racing)

RB740- E39

3 litre

Block only- South Africa

RB860-E40

3 litre

Dismantled

Rebuilt as 2.5 litre 830 for Bib Stillwell, ex-Brabham BT31, later Ian Ross and fitted to his Elfin 600C in the modern era

RB860- E42

3 litre BRO 1968

Fitted to Peter Simms BT26 in the modern era

(A Lewis)

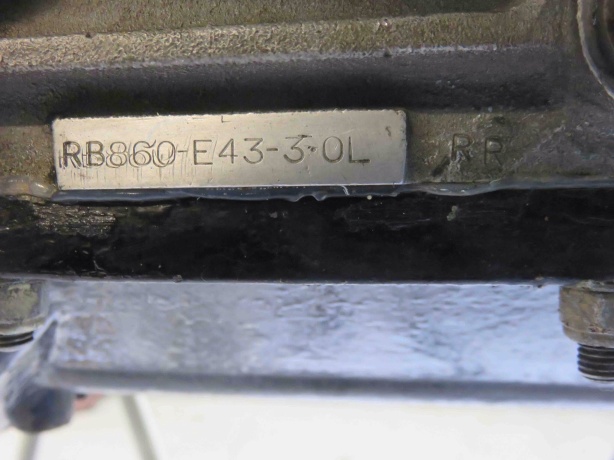

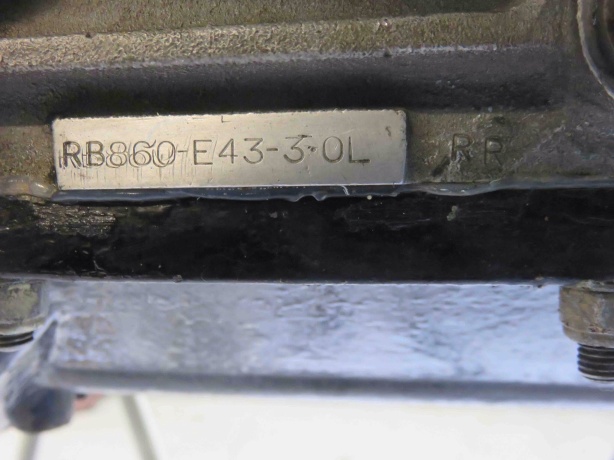

RB860- E43

3 litre

Scrapped

In recent times built by the late Don Halpin into a 2.5 litre Tasman engine for the Will Marshall owned Brabham BT31 and most recently fitted into the Aaron Lewis restored ex-Brabham/Jane/Harvey Brabham BT23E

RB860- E44

3 litre

Not completed?

RB860- E45

3 litre

REDCO display mag block

The 700 and 800 Series ‘conventional’ four-valvers…

Note that the short 800 Series block engines were of either 2.5 litres ‘830 Series’ SOHC parallel two valve, crossflow type or 3 litre ‘860 Series’ DOHC four-valve crossflow type.

The large capacity four valve engines were all ‘760 Series’ of 4.2 ‘Indy’ and 4.8 and 5 litre ‘Matich SR4’ type

(B Watson)

Jack Brabham, sprouting wings- Brabham and Ferrari led that charge in F1, at Oulton Park contesting the International Gold Cup in August 1968.

He started the race one second adrift of Graham Hill on pole and DNF’d with an oil leak- Jochen lasted 8 laps less with a similar ailment. Stewart won in a Matra MS10 Ford in a year of dominance for Cosworth.

The background to the F1 860 V8 for 1968 we covered in the context of the failed radial valve 850 experiments.

As outlined, the net effect of persevering with 850 for too long was an under-developed 860 for 1968.

The 3 litre Repco Brabham 860 Series V8 was almost as nicely packaged as the ‘industry standard DFV’ albeit a bit heavier and was not built to be used as a stressed member of the car as the DFV was specified to be by Colin Chapman to Keith Duckworth.

RBE Chief Engineer Norman Wilson ‘The Cosworth DFV was different to the Repco-Brabham 860. The Cosworth engine was the first engine to be designed as a stressed member (in fact I think Vittorio Jano’s 1954 Lancia D50 may have that honour). The design philosophy of the crankcase and oil scavenging were all totally different. The 860 was a heavier but I think stronger engine, while the Cosworth was running sort of 9000 rpm we should have been looking to run 10000.’

A 400 bhp, reliable Brabham BT26A RB860 was a winning chassis in 1969 as indeed, twice, the BT26A Ford DFV was.

There were plenty of 860 engine failures during 1968, the fundamental problem was similar to that experienced with the DFV in 1967- torsional vibration of the valve gear which ‘…was wrecking the cam followers. And the solution to the problem was fairly simple. All we had to do was modify the cam drive like the Ford DFV engine and we could have fixed it.’ said Wilson interviewed in Simon Pinder’s Frank Hallam biography.

(Sutton)

Wilson ‘What happens is that at certain speeds the front of the crankshaft will tend to go a little bit like a tuning fork and as it rotates the front of the crankshaft oscillates back and forth and the oscillation is transferred up through the timing gears. It was making two of the camshafts do the same thing. So when the cam lobes were going around they were ruining the cam followers. The Cosworth engine had a little spring gizmo in the first timing gear to absorb this so it is not transmitted through the whole system.’

‘And Frank realised we needed something like this (after a discussion between Cosworth’s Mike Costin and Norman Wilson) and we were working at doing that when Charlie Dean arrived on the scene and said he thought it was a lubrication problem. That was the cause of a fair bit of argument between Charlie and i.’

‘The engine could have been as good as the Cosworth, there is no problem about that. It was a tiny bit heavier than the Cosworth but that really wasn’t the problem because we could have put the thing on a diet and saved some weight. The first thing we could have done is changed aluminium components to magnesium, so there was room for weight saving’.

Wilson ‘Really we should have fixed the camshaft drive, got rid of the rest of the projects and just gone for it’, where ‘gone for it’ means just concentrate on F1 not do F1, Tasman, Indy, Special Projects and customer engines…

Rodway picks up ‘the rest of the projects, ‘…I agree with Norm’s claims about other projects. We had one of our best engineers working on the crankshaft lathes from BMC. We were designing and building the Pontiac (303 cid race engine) for GM. We also machined a batch of Volvo cylinder heads and spent many hours dyno and car testing. Let alone machining Frank’s Austin 1800 cylinder block and fitting a Derrington head and Weber carbies…’

Whatever the commercial imperatives, all of the above impinged on the limited resources the team had for core programs in 1968- F1, Indy and customer needs globally.

Repco RB760 4.2 litre ‘Indy’ V8 (Repco)

Wolfe of the engine above ‘Possibly a 4.2 Indy engine, one of 3. It has the later sump with the scavenge pump fore and aft’. Tait ‘Its quite possibly the one used by Jack. Some years ago he told me that one of the two engines he had disappeared after being lent to Goodyear in the US’.

The one that’s in my SR4 at present seems to have been one of the first, if not the very first 4.2 quad cam. Its throttle slide upper cover has been milled from solid aluminium as opposed to later ones which were of cast magnesium. I came by this engine with help from Aaron Lewis who knew that Les Wright had removed it from his Brabham Buick in order to fit its Buick based engine- the engine number panel is blank. I have no idea how the Repco engine ended up in the Brabham Buick. The Matich SR4 didn’t ever race with a 4.2, though that’s all I had until I built up a 5 litre…’

Rodway Wolfe in relation to the V8 missing in the ‘States ‘The story I got was that the engine was being used by the Gulf Oil Company for research! I did try a few avenues a few years ago and drew a blank. As far as I recall…E35, E36 and E37 were the 4.2 Indy engines. I don’t recall what the 2.8 was. I still have the intake manifold for the disbanded 2.8’.

(I Lees)

Ian Lees fettling Jochen’s BT25-1 at Indy in 1968.

Tauranac’s BT25 was famously Brabham’s first monocoque chassis, interestingly, despite the BT25 and F1 BT26 coming together at MRD at about the same time Tauranac chose a tried and true spaceframe for his new F1 design- albeit with the use of sheet aluminium riveted and glued to the frame to add rigidity.

It does make you wonder why he didn’t do a variant of the Indy chassis for F1 in 1969- perhaps unwanted weight is the answer.

RB760-E35

4.2 litre

BRO Indy campaign in 1968/9

Fitted to Brabham BT25 chassis- engine despatched from Maidstone to Indianapolis at 1.30 pm on 28 May 1969, together with a very comprehensive inventory of spare parts running to 5 typed foolscap pages, inclusive of a 700 Series block.

Rod 29 February 1969, ‘Ordered new gear-cases for Indy engines to be cast in aluminium due to cracking’

Rod’s diary notes the departure of Norman Wilson and Don Halpin to Indy on 13 May 1969, and E35 sent to the US on 6 May 1969

One of the BT25’s, with 4.2 litre ‘760’ in situ at MRD in early 1978 (P Blood)

The photos are of the BT25’s being built at the MRD works, at Byfleet, Surrey beside the canal. Many readers will be wistful at this view because quite a few of you did a stint working in this factory in either the Brabham or Ralt era.

RB760-E34

4.2 litre BRO Indy campaign in 1968/9

Fitted to Brabham BT25 chassis

Rod Wolfe’s diary records that on Thursday 11 April E34 4.2 litre ‘off dyno’ so it is safe to assume the car with engine fitted at MRD is the chassis raced by Jochen in 1968, fitted with engine E34, given the other engine, E35 did not leave Melbourne until 28 May 1968.

Three BT25 chassis being built at MRD in 1968 (P Blood)

‘The photos are of the two BT25’s being built early in 1968. It’s probably the third tub behind. It was not used until revised into the BT32 Offy-turbo Jack raced in 1970’ wrote Aaron Lewis who restored one of the BT25’s a couple of years ago, and fitted with engine E34- some of you may have seen David Brabham race the car in a tribute to Jack at Goodwood.

Lewis ‘I found my car hanging upside down from the roof of Bill Simpson’s North Carolina shop’.

RB760-E36

4.2 litre

Scrapped

Now owned by Nigel Tait- one of the engines fitted to his Matich SR4

BRO Indy campaign in 1968/9

In 1968 BRO entered one car for Jochen Rindt, he qualified sixteenth of thirty-three cars and was out after 5 laps with a holed piston, the race was won by Bobby Unser in an Eagle Offy.

Rod Wolfe’s theory in response to my question as to why the engine went kaboomba is as follows; ‘ No-one ever came up with an answer! Personally my theory is as follows. But I only hold an A-Grade Mechanic ticket so you might need greater brains than mine! The 4.2 Indy engines ran the later type sump with two scavenge pumps (one each end) the original Irving system used one scavenge pump at the front with an inertia valve in the sump.

Under acceleration the valve moved backward and opened a gallery at the sump rear and under braking the oil all moved forward and a gallery opened in the front. The 4.2 Indy engine, as said above, had a pump at both ends and was pumping oil mist and oil and air continually.

Jack had problems with this sump system with the gaskets being sucked into the sump. He cured this by fitting an extra screw between each original 5/16 inch stud. As with lots of engines the RB V8 uses oil spray under the piston for lubrication and cooling the piston crown. My own thoughts have always been that the combination of nitro-methane (fuel) and “perhaps” a diminished oil spray internally made that little difference and caused the detonation. All engines have a difference in cylinder temperature dependent upon coolant flow or their location in the block. I won’t bore you any more but the picture shows (below) it ran very hot’.

(R Wolfe)

Speaking of pistons, Nigel Tait chips in ‘Incidentally you may recall that our pistons were made from castings made at Richmond (Repco) by Jim Hawker. I understand that when Jack appeared at Indy with the 4.2 the scrutineers asked for the Certificate of Forging and they couldn’t believe the pistons came from castings!’

‘Jim Hawker was our Foundry Manager at Richmond. I’m pretty sure he accompanied Phil Irving as ‘tail end charlie’ on the first Repco Reliability Trial in the Chamberlain tractor. He was originally at Rolloy when it was owned by the Chamberlain family. He also made a V8 Peugeot from two 403 cylinder blocks. About as bizarre as the diesel Holden engine made by the delightful Ruggero Giannini but that another story!’ Nigel concluded.

I’ll avoid the Jim Hawker tangent other than to say his role at Chamberlain is covered in this article;

Chamberlain 8: by John Medley and Mark Bisset…

The soundness and competitiveness of the 860/760 design was proved by Peter Revson’s performances with it in 1969.

He started the 500 from slot 33 and finished fifth and was stiff not to win the Rookie of The Year title- Mark Donohue started from position 4 and finished seventh and bagged the rookie award.

Doug Nye wrote that Peter’s Brabham Repco Indy result ‘effectively began the elevation of Revvie’s career from self-funded dilettante privateer into a genuine front-line professional racing driver.’

Later in the season Peter drove his BT25 760 4.2 to a win in the Indy 200 GP at the Indy Racing Park road course on 27 July.

This event was run over two 100 mile heats, Peter won heat 2 from Q3 ahead of Mario Andretti, George Follmer and Al Unser and was third behind Dan Gurney and Al Unser in Eagle Ford and Lola Ford respectively in the other heat- winning the event overall.

The point to be taken from both the Indy 500 fifth place finish, and the Indy 200 win is that the 4.2 760 engine seemed to have overcome the 860 ‘gremlins’ from the year before albeit without fitting the anti-torsional vibration spring ‘gizmo’ Norman Wilson wrote of earlier.

I wonder if for whatever reason the torsional vibration of the valve-gear was in part a function of the different blocks- the tall 700 and short 800? That is, the tall 700 didn’t have it whereas the short 800 did? The maximum quoted revs of both engines were the same- 8500 rpm for the 3 litre 860 and 4.2 litre 760.

The 760 4.8 litre and 5 litre V8’s fitted to Frank Matich’s Matich SR4 also did not have the valve-gear problem. The Matich example is not as good a test of the engine design’s endurance as the Indy successes in that the Australian Sportscar Championship rounds were much shorter and the competition nowhere near of the same depth- in essence FM was not pushing the SR4 as hard as Revson was his Brabham BT25. John Mepstead, who looked after FM’s 760 engines in 1969 and into 1970 can give us a perspective on this.

Its an intriguing question, keen to hear theories from you engineering types.

840 2.8 turbo inlet manifold from Rodway’s Repco Collection

RB840-E?

2.8 litre turbo-charged BRO Indy campaign 1968

Rod ‘800 block for 2.8 litre started’ 17 June 1969

This is a mystery engine in terms of its number. There is no doubt it was built and tested but none of the lists I have access to discloses its number.

Norman Wilson ‘Ron Tauranac wanted it. Ron felt we could have won with a turbo engine. In 1968 I had visited AiResearch and another turbocharger maker in Chicago. The engine used the 40 Series heads and we got some pretty good power out of it. We had a carburettor Jack supplied from BRM which was probably not a clever idea because with the very high G-forces which you get at Indianapolis there’s no way the thing would have worked properly’.

‘We needed fuel injection so we had proper control from both the drivers point of view and from a fuel consumption point of view because there was a fuel consumption limit…But fooling around with that SG carburettor and all that stuff was just another blind alley. We should have sat down and thought it through and not done it. We should have done the 4.2 litre and left it at that.’

Evolution of Cylinder Heads and Budget Constraints…

‘The first (20 Series) heads were cross flow but incorporated a throttle slide track as part of the casting, the 40 Series are centre exhaust and inlets in the valley…’- Wolfe.

Rod Nash then chimed in ‘…the 30 Series followed the 20 Series but Ron Tauranac vetoed the 30 Series as he wanted exhaust pipes in the Vee, for a more streamlined effect- the 30 Series didn’t eventuate until much later.

‘When we were testing new conrods, we didn’t want to risk compromising the 40 Series heads as these were our production heads at the time. So (when) we assembled the 30 Series heads and used then on the test engine, and found they gave more horsepower than the 40 Series. The result was too late to use in F1 (the first 830 2.5 was installed in the back of Jack’s BT23E at the final Tasman round in February 1968) so we used the 30 Series in the later Tasman 2.5 engines’.

Tait ‘We only had one size of the magnesium housings for the inlet tubes, so the only choice was to vary the height’.

Wolfe ‘Nigel is right there as unlike some other F1 engines our problem with the RBE engines was not getting air into the engine- it was to burn the fuel/air more efficiently that which was getting in there’.

‘In the 2.5 the longer inlets enabled the ability to use the air column compression effect to stuff a bit more in as the valve closed. This the area of building racing engines that costs so much to research. When we built the 760 quad-cam 5 litre we used the same valve sizes in the 860 3 litre quad-cam. Repco just didn’t have the money to spend on playing with valve sizes or inlet diameters’.

Peter Molloy then commented ‘What you are trying to say is you didn’t have ‘induction energy’ that increases the port velocity, called the ‘supercharge effect’ that gave you a later closing valve, one of the problems you had Rod was poor combustion. But we all go through theses scenarios, I loved getting the end result, understanding the energy that is a available in engine geometry.’

‘Remember the Three C’s- Calculators, Common Sense, Compronise’

‘And the fourth is Cash!’ added Tait.

1968-1969

Tasman 830’s…

Here is a rare photograph of German racer Dieter Quester in Bob Harper’s ex-Cooper Elfin 600C Repco ‘830’ 2.5 E29 during the 1969 Macau Grand Prix weekend.

Three 600C’s were built- this one, an FVA engined car for Hengkie Iriawan and a third for John McCormack. The latter was initially fitted with a 2.5 Coventry Climax FPF from John’s ex-Brabham BT4 1962 AGP machine, and later with a 740 Series RB V8 E15B for the final period of the ANF2.5 formula in 1970.

Garrie’s car was sold to Steve Holland (or was it Bob Harper) after the 1969 JAF Japanese GP at Fuji. Steve Holland was ‘out of his depth in the 600C at Macau’ so Bob Harper considered giving the drive to Dieter Quester who did a 2 min 41.5 seconds lap- jumping out of the BMW he raced that weekend.

Eli Solomon wrote that ‘…eventually Holland got the drive. Steve Holland’s issues with the #87 Elfin Repco V8 ended on lap 37 when he pulled out with suspension troubles, having been in 4th position’. Quite how he could have jumped out of the BMW sent for him by the factory into the Elfin is a bit clouded- but Quester’s few laps at Macau in 1969 is an obscure bit of Elfin and Repco history.

Further Elfin/Repco history is that GC took his only Gold Star round win aboard this chassis at Mallala in October 1969 when the car was back at Edwardstown for a freshen/rebuild.

Malcolm Ramsay raced the car in Asia in 1970 and throughout the Gold Star, won that year by Leo Geoghegan’s Lotus 59B Waggott.

RB-830-E29

2.5 litre

BRO –

One engine initially built- and fitted into Brabham’s BT23E in the final 1968 Tasman round at Sandown for the race

Rod ‘8 January 1968 E29 830 2.5 on the dyno 278 bhp @ 8750 rpm’

Then to Elfin Racing Cars Garrie Cooper on 21 February 1969- fitted to GC’s Elfin 600C, raced in Asia then to Malcolm Ramsay as his 1970 Gold Star car.

Then fitted to Henry Michell’s Elfin 360 sportscar in 1971 after the end of the 2.5 litre ANF1- and still installed in that Elfin.

RB840-E31

2.5 litre

BRO 1968 Tasman for Brabham’s BT23E

Then to Bob Jane

RB840-E32

2.5 litre

BRO 1968 Tasman for Brabham’s BT23E

Scrapped

RB-830-E50

2.5 litre- Elfin Racing Cars Garrie Cooper- fitted to GC’s Elfin 600D, his 1970 Gold Star contender

Then fitted to Phil Moore’s Elfin 360 sportscar in 1971, as it still is

(The Matich SR4 fitted with 4.8 litre 760 ‘E41’ Repco)

Big Bertha- The Big Repco’s…

Frank Matich’s new Matich SR4 at Warwick Farm’…photo taken on the day of the cars first test run late in 1968, the ZF gearbox was changed to a Hewland LG gearbox in November 1969′ advises Derek Kneller.

‘It took at least 8 hours to change the ratios in the ZF ‘box due to the synchromesh, and you needed specialised tooling, it was easier to change the crown wheel and pinion. FM had two ZF ‘boxes set up with different ratios, if was far easier to change the whole ‘box’ Kneller recalls.

RB760-E41

4.8 litre

Frank Matich for the Matich SR4, winner of the 1969 Australian sportscar championship- this was his race engine throughout 1969. The motor was assembled by ‘Meppa’- John Mepstead, dyno tested and tweaked by him and then maintained by him throughout the year as he travelled with Matich during the season

Engine now owned by Nigel Tait, together with the SR4- we wrote an article about this car a while back;

Matich SR4 Repco…by Nigel Tait and Mark Bisset

See RB760-E48 ‘A second 760 4-cam was built when I came back from Sydney, a 4 cylinder 2.4 litre engine was built and fitted to Frank Hallam’s Volvo’ wrote John Mepstead.

Frank Matich SR4 and RBE General Manager Frank Hallam at Oran Park in late 1968 (Repco)

1969-1970

RB830-E47

2.5 litre

BRO for Brabham BT31

Rod Wolfe helped Jack assemble BT31 at Maidstone as told in our article linked below. Its interesting looking at Rod’s diary entries that week prior to the final, Sandown 1969 Tasman round.

Wednesday 12 February

BT31 arrived (unassembled in a box) at 3.45 pm. Brabham arrived at 8.30 pm- ‘BT31 assembly commenced’

Friday 14 February

4.15 pm took car to Calder for test

Sunday 16 February

Sandown International, 1st, 2nd and 3rd Chris Amon Ferrari Dino 246T, Jochen Rindt Lotus 49 Ford DFW, Jack Brabham, Brabham BT31 Repco 830

Rod ’28 February 1969 E47 ready for BT31′

7 April 1969 Rod records Brabham’s Easter Bathurst ‘Bathurst 100’ Gold Star win in BT31 and his lap record of 2:13.2 seconds

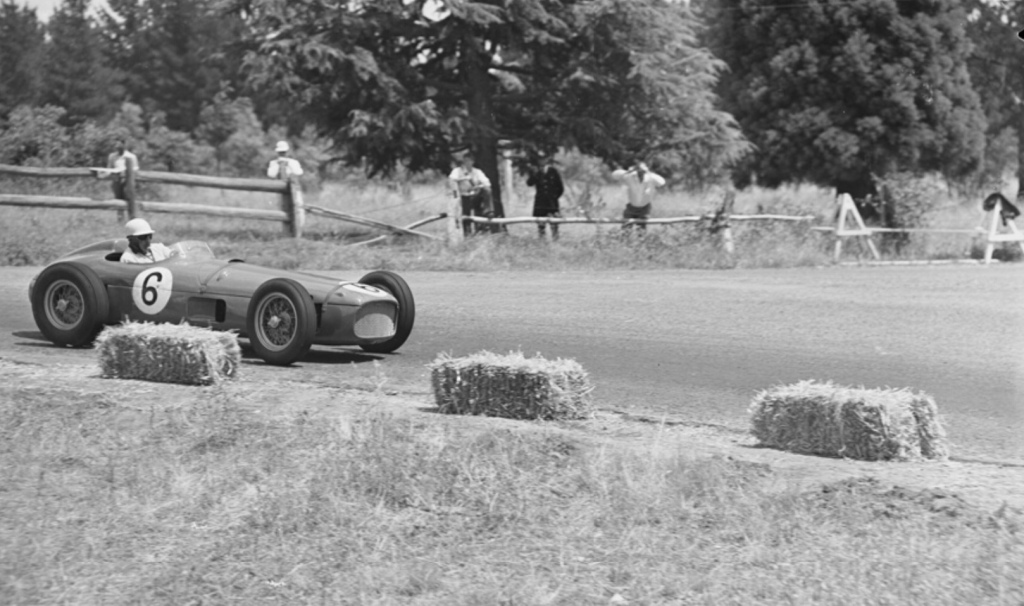

Several RB 830 2.5’s were built, the photo above is of Jack in BT31, his 1969 Tasman car, at Sandown the story of which is told here.

Rodway and I wrote an article about BT31- a car he owned for many years; https://primotipo.com/2015/02/26/rodways-repco-recollections-brabham-bt31-repco-jacks-69-tasman-car-episode-4/

Rod Wolfe advises both ‘BRO’ 830 V8’s were provided to Bob Jane Racing for use by John Harvey in Jane’s ex-Brabham, Brabham BT23E and the Bob Britton/Rennmax Engineering built ‘Jane V8’ Harvey raced in the 1970 Gold Star.

Where are these two motors now- of which E47 is one?

Brabham in BT31 with, probably engine E47 830 2.5 fitted at Sandown in early 1969 (R MacKenzie)

RB760-E49

5 litre- Frank Matich for the Matich SR4