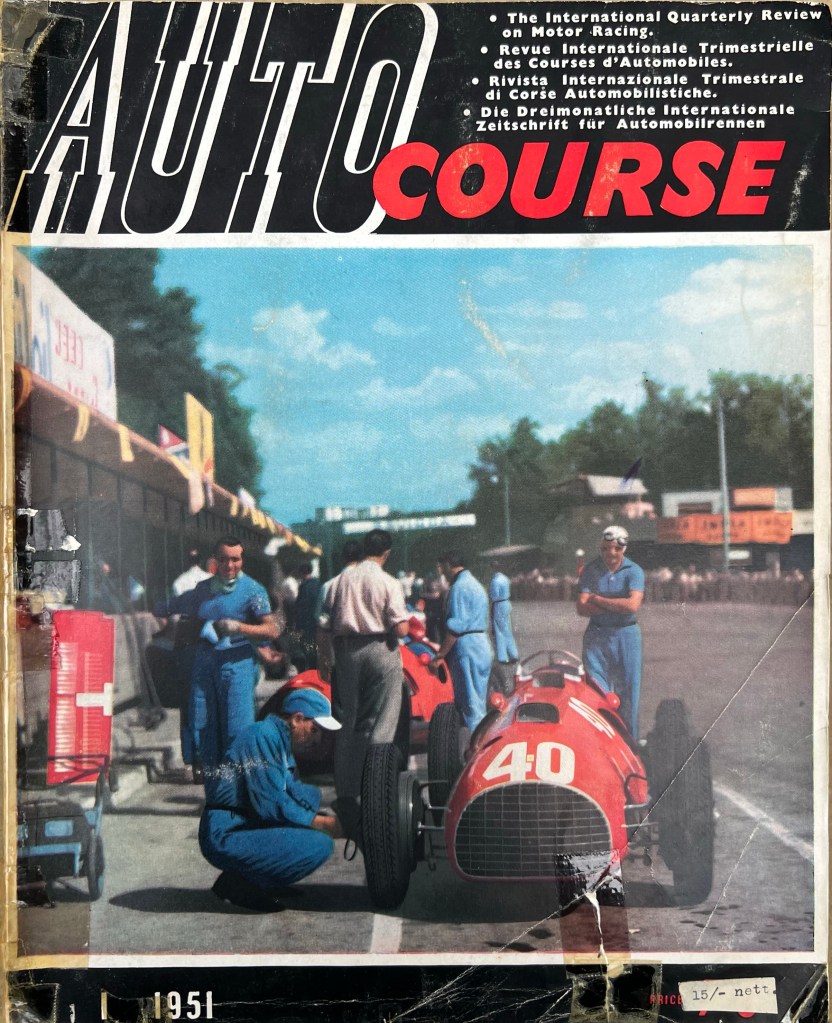

The Ferrari pits during the Grand Prix des Nations weekend, Geneva, July 30, 1950.

Alberto Ascari at left with car #40, a 4.1-litre Ferrari 340, the car behind is Gigi Villoresi’s 3.3-litre Ferrari 375 with the man himself at right (I think). Typical of the era, factory Alfa Romeo 158s finished one-two-three: Juan Manuel Fangio from Emmanuel de Graffenreid and Piero Taruffi.

“It took me five years to get this Autocourse and a whole lot of others from the widow of the owner!” my friend Tony Johns said with a chuckle. I’ve always been an Automobile Year guy, by the time I realised Autocourse was THE racing annual I’d already got the Automobile Year bug and started what became a 20 year journey to collect a set.

It was another set, Blommie The Great 38’s fabulous tits that led me in the wrong direction. Camberwell Grammar School appointed 25 year old, very statuesque Miss Blomquist as a librarian in 1971-72. Of course one couldn’t just sit in the library with ones tongue on the floor, it was while cruising the aisles trying to look like a serious student on my furtive, very frequent perving missions that I came upon Automobile Year 18, the 1970 season review. And so the obsession began, I was soon surgically removing the best photographs of the school’s Auto Years with a razor blade and adding them to my bedroom wall where scantily clad Raquel Welch had pole position.

It’s been great to have the very first of these learned journals for a week to peruse, read and enjoy. The 140 page, then-quarterly, cost 15 shillings in Australia and was distributed by Curzon Publishing Company, 37 Queen Street, Melbourne, not an outfit familiar to me but will perhaps ring a bell with some of the older brotherhood?

Two features are reproduced: one on F3 by Stirling Moss and another by Alfred Neubauer on the ‘Brains’ of the racing driver.

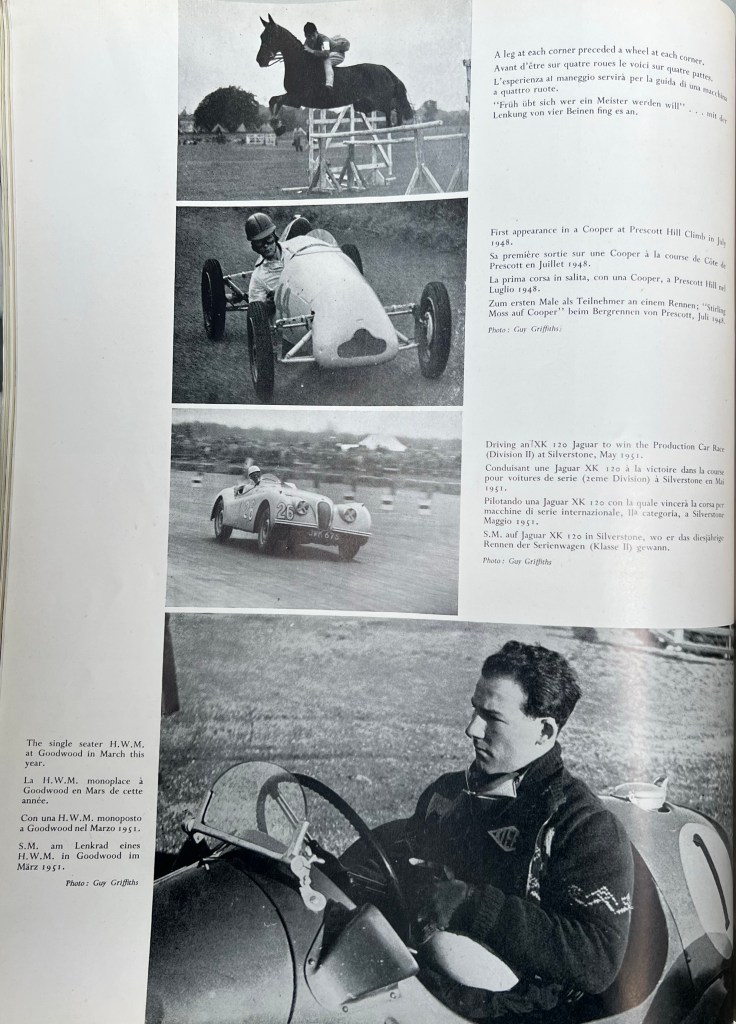

Walt Whitman once wrote ‘stout asa horse, patient, haughty, electrical’ but when first set to control one of the breed, at the age of six, it seemed to me neither stout nor patient. Reference to a horse may seem somewhat out of place when one begins to consider a motor racing career, but the equine enthusiasts talk about a good pair of hands and a good seat, and I am sure that both are just as necessary to the racing driver. If you are going to ride a horse seriously, as I did, then you must think one step ahead of it. A racing car also appears to have a personality of its own, and the driver must be equally facile at anticipating its behaviour.

Certainly I have never thought that the time I spent astride four legs as being anything but invaluable to subsequent control of four wheels, and my fourlegged career went on for ten years. Apart from the lessons it taught, it was even more directly concerned with the first appearance of ” Stirling Moss (Cooper) ” in a hill climb programme. Prize money won in the jumping ring was the financial foundation of the purchase of that Cooper.

It seems astounding now to recall that in 1948 British motor sport was centred on sprints and hill climbs, and that 500c.c. cars were still a somewhat despised novelty, mostly produced by enthusiastic owner drivers. I took delivery of one of the early production Coopers and it really is impossible to consider those days without digressing to praise the foresight and ability of the Coopers, both father and son, for without the reputation built up by their products half litre racing could never have reached the point where it won International recognition as Formula III. The only pity is that France and Italy appear yet to need to discover their equivalent of these two enthusiasts.

If they could, and were thus able to get equally successful cars into production, I am sure that there would not be the present move towards a change in the Formula.

Since those days the design of half litre cars has settled into a fairly consistent pattern of rear mounted motor cycle engine driving the back axle by chains via a motorcycle gearbox and it was the excellence of the available motorcycle components which played another big part in boosting the possibilities of Formula III. Perhaps the biggest advance in the past three years has been the mating of reliability with steadily increasing speeds. Maximum speeds have not changed so much, but circuit speeds have, as the result of patient chassis development, and though in 1951 circumstances will prevent me from driving half litre cars as much as in the past, the lessons learned at the wheel of these flyweights can be applied to the much trickier problems of heavier and faster machines.

Giving around 45 b.h.p. the more prominent 500 c.c. engines of today will propel a racing car at 100 to 105 m.p.h. and because the car is so low and so small this seems to the driver a pretty high velocity. It is only when one changes to a heavier car that one realises just how far liberties can be successfully taken with a car weighing perhaps 6 1/2 cwts all up.

Half-litre racing is always fun, and as far as the British scene is concerned is the most keenly contested class of all, because it has given so many people the opportunities which had previously been the prerogative of Continental drivers. I for one could never have hoped to motor race seriously but for the reduction in cost brought about by the 500 c.c. class and instead of being the proud possessor of the British Racing Drivers’ Club’s 1950 Gold Star would most likely have been, at the best, an unknown also ran with some sports machine in club events.

It may comfort some to know also that the first entry I submitted, fresh with enthusiasm at the prospect of taking delivery of the Cooper, bounced back at me.

The next step forward from the Cooper 500 was the Cooper 1000.

I say step forward without belittling the smaller car, but because I imagine that the goal of every racing driver is Formula I. That is a long road which I have yet to traverse but just how tricky a road it is I am learning almost every weekend this summer of 1951. I was fortunate in having parents every bit as enthusiastic about motor racing as myself, and at the same time a good deal more experienced when they suggested that one did not know what motor racing was all about until one had been on the Continent. With a Cooper 1000 I set out to see for myself in the latter half of 1949, and how right they were. The foray achieved some moderate success, not so much in the results, but in the experience gained and the feeling of confidence induced, and above all that I had something definite to offer to John Heath when he was looking around for drivers for the H.W.M. team. On his side, John could offer a car which was magnificently reliable and always pleasant to drive. The results achieved in 1950 are a matter of history, and there was only one snag. Excellent as the cars were they were never quite fast enough to win against a Ferrari, and we kept on meeting Ferraris.

This is not a criticism, but a simple statement of fact of which John himself was only too well aware, and which he has made every effort to remedy for 1951 by the most ingenious use of available materials. What was always a delight to me was to be a member of a well turned out team of cars bearing the British green which always arrived on the starting line a credit to their sponsor.

A racing driver usually gets some stock questions put to him by the layman, which can be paraphrased into ” How fast can you go?” “Which car do you like driving best? ” and ” What was your most memorable race?” My answer to the first is that speed is purely relative. The real art of motor racing and, for that matter the real excitement, is in negotiating an 8o m.p.h. corner at 90 m.p.h., for it doesn’t matter whether you do 100 or 150 m.p.h. down the straight.

As for the other two questions, the answer to the second is usually the car I am to drive next, and to the third, my last race. If one is to succeed, it has always seemed to me that one must be entirely engrossed in the race in hand, and whilst drawing on the experience of the past, memories of races as races are wiped out by the task of the moment. In any case, the last person to approach for any coherent picture of a race is a driver who was taking part in it.

The same sort of thing applies to cars, and one has to completely identify oneself with the machine of the moment, until you almost approach the state of believing that that is the only car which you really know how to drive.

Certain races stand out because of particular objects achieved, such as last year’s Tourist Trophy as being my first experience of a really fast heavy car, but the race itself was one of the easiest. So much so that I let my mind wander to external problems and made an excursion down an escape road. At Silverstone last August my chief reaction was a pleasure not so much in winning but in beating the late Raymond Sommer on the only occasion we met in reasonably comparable machines.

At Bari it was natural to feel a similar pleasure in bringing an H.W.M. home third behind two type 158 Alfas, because that was a result so much better than any of us had hoped for.

That is really the biggest satisfaction of all; doing just a little bit better than one expects when faced by a new situation and these notes are being written on the eve of what I am expecting to be my memorable race of 1951, the Mille Miglia and Le Mans.

The ‘Brains’ of the Racing Driver

By Alfred Neubauer, Team Manager of Mercedes Benz

The racing driver fixes hisses on the starting flag; his nerves are the keyed up to the highest pitch, for he knows those few moments of suspense, seeming like hours, will soon pass and the flag will drop. Another 10 seconds to go, slowly he pushes his gear lever into first…5…4…3…2…1 off!

With only 5 seconds left, he revs the car up to half its maximum, gently lets in the clutch and revs, further. The flag drops and with care to ensure that the back wheels do not spin, thus causing the car to run sideways, he shoots forward like a bullet from a gun.

Even for this first phase of the race – the start – the tactics involved have been thoroughly worked out by the team manager as a result of his observations during training. The popular opinion exists that in every racing team one or two drivers are chosen to set the pace. This, it is believed, will compel the other competitors to greater speeds. They will strain their engines, weaknesses will become apparent, resulting in their elimination, thus giving the driver, selected as the eventual winner, the opportunity to choose his moment and then drive through to clear victory. The opinion that such tactics are dictated is absolutely wrong. In fact, they evolve from the experience and technique of the driver himself.

The basic rule is as follows: ” Drive your machine within your own capabilities as fast as you can – but do not overstrain either yourself or your machine.” One rider must be added to this. Both car and driver, of course, must be subjected to some strain, but a first-class driver will know at what point this strain becomes excessive and for what length of time any strain can be borne without collapse. After continual experience, maximum powers of endurance become clear. Some drivers use both their cars and themselves unsparingly from the start and, consequently, collapse after a short time. They either drop back or are forced to retire. Others are capable of taking the lead from the start and holding it until the end of the race. There is yet a third kind of driver who knows the individual characteristics of his rivals and plays upon them. They purposely keep on their tail, in the meanwhile economising their own forces, and wait for a suitable moment to overtake them. The nerves of some drivers are unable to bare being trailed, and again there are those who remain completely indifferent to it.

Drivers can only know their position in a race so long as they keep within sight of one another. Once the leading drivers have got so far ahead as to lose contact with the rest of the field or when cars begin to drop out or are forced into the pits, then it is no longer possible for the drivers to know their position. It is at this juncture that the work of the pits commences. They are the brains of the racing driver and are led by the team manager. In aviation radio communication between the flyers of a squadron has long been recognised. So far as motor racing is concerned, however, this method of contact between the team manager and driver has not been introduced.* Thus for them the only means of communication is visual. It is, however easily understandable that the simplest method is the best because the driver’s attention must, under all circumstances, be concentated solely on his own car and the road ahead. A further duty of the pits is to inform the driver of the number of laps he has already covered and also the laps remaining. Each driver signifies that the message communicated to him has been understood by nodding his head.

An inexperienced team leader will be astonished when only a few laps later, by means of a circular movement of his hand, the driver indicates that he once more wants to know the number of laps that remain to be covered. This is, however, not exceptional and the explanation is given more often than not by the driver at the end of the race. He has to admit that very shortly after he received the first message he completely forgot its contents. For the driver the most important signals are those indicating his position in the race and the intervals that separate him from his opponents. The knowledge of his exact position dictates his policy. If the lead over his opponent is increasing, then naturally he will relax and thus economise his own forces and those of his car. If his lead is decreasing, then he will do everything in his power to increase once more the distance between himself and his rival. Similarly it is imperative for the driver lying in second place to know the distance between himself and the leader. From this it follows that he must be careful that his present position is not threatened by those who lie yet farther behind.

Naturally the team manager prefers those drivers who take the lead from the outset and hold it throughout the race without straining either themselves or their cars. It is only during a race itself that the driver can know whether he can have some moments’ relaxation or not. In some racing teams first-class drivers are fully aware of the potential weaknesses of their team mates and their cars and from the very start they remain in second place, thus conserving their own forces. As soon as they realise that their team mates’ powers are exhausted, they can immediately take the lead. The brains of the racing driver -the pits – have also to take such considerations into account, and must ensure that the driver who has made his way through the field and eventually takes the lead maintains the position he has succeeded in gaining. There have been instances when these tactics have been employed with great success. It is then the duty of the team manager to inform both the leading driver and his followers at each lap of the distance between them. It must be made clear to the driver lying in second place that he has lost his lead and would do far better to content himself by remaining in second place rather than force his car out of the race.

The price of driving as fast as driver and car permit is often very high. It should take very little experience for the driver to be fully aware of his own capabilities. So far as his engine is concerned he will have received precise directions and he will have been told by his testing engineers of the precise amount of revolutions permitted. However, it is only natural that he should make a point of ensuring that these instructions have not been too cautious and he will certainly confirm for himself to what extent his motor may be over-revved. The experience of former years has shown that drivers who have been given precise instructions that their revs should not exceed 4500 have, some years later, admitted reaching 6200. When a driver confines himself strictly to the instructions of the technicians and a team mate overtakes him, it becomes quite obvious that this team mate has exceeded the limits given to him. Here temperament plays its part, for the decision has to be made whether he will exceed his limits or whether he will observe the technical instructions to the letter and bear in mind the increased lasting powers of his engine.

Generally speaking, the driver who is bound by technical instructions has an advantage over those drivers who themselves assisted in the building of their engines. The latter, whilst testing, will have discovered the limits which the construction of the engine has imposed. Indeed it is fair to say that it is no advantage whatsoever to a driver to be himself a builder or testing engineer. He is naturally hampered by the knowledge of his own technical experience.

Perhaps this is a suitable moment to say a few words about “luck” in racing. If a driver fails to take into consideration the limits imposed by the technicians and a piston rod breaks or some defect in the engine forces him to retire or his tyres do not stand up to his way of driving, then he will have the satisfaction of knowing that all will say:- “What bad luck ! ” Conversely, one member of a team finishes and the others are forced to retire, invariably the latter will exclaim :- ” How lucky he was! “

Technically speaking, 95% of ” luck ” in racing is dependent upon the preparation of a car. This preparation begins at the first moment of building. The other 5% lies in the hands of the driver, whose “feel ” permits him to get the maximum value out of his car. There are drivers on the Nürburgring who use up their tyres in six laps and are indeed slower than those who do not have to change their tyres for eight or even ten laps. A more subtle method of driving, a more even use of the engine on leaving corners and a softer application of the brakes differentiate a good driver from a better one.

As in every activity which demands talent so in motor racing. There are many enthusiasts, but few become champions.

All these facts prove how many conditions have to be fulfilled before success in a race can be achieved. The popular complaint of housewives :-” You have eaten in a minute what I have taken hours to prepare,” would perhaps be even more suitable to motor racing!

It is not the obiect of this article to consider the many hurdles which must be cleared before the racing car eventually reaches the track:- the planning of the design according to the formula given, the design itself, the manufacture of the parts, the assembly and testing. Our task commences only from the moment when the car leaves the factory and proceeds to a race, there to prove the quality of its design and justify the work of preparation. These preparations are no more than stages on the road to victory.

The work is undertaken not merely to prepare a car for one particular race, but also with a view to its chances of success over its rivals.

Experience gained by entering for the same race year after year greatly assists the designer in his attempts to reach perfection so far as one particular course is concerned. Often drivers entering a race for the first time are taken unawares by the peculiarities of the track which had they had opportunities of practising thoroughly earlier, could have been avoided without difficulty. Practise on non-permanent tracks presents complications as it is practically impossible to close circuits to the public so as to enable practising to take place. Consesequently, the preparation of cars for non-permanent circuits is considerably more difficult than for permanent circuits which are open to racing cars at all times of the year. To list but a few-the choice of the right transmission, the measurements of fuel requirements and the wear on brakes and tyres are factors which must depend entirely on the circuit to be raced.

Many years ago, the principle of fitting streamlined bodies to cars for very fast circuits was accepted. Nevertheless, without comparative tests it is not so easy to decide whether this style of bodywork is most suitable to any track. The streamlined bodies with their attendant lack of wind resistance have the advantage in acceleration and are preferable when high maximum speeds are required. This, however, is offset by the decrease in braking power with the resultant strain on the brakes. On the former Avus circuit, where there are two parallel stretches of ten kilometres and long curves, this disadvantage was not apparent. Many, streamlined designers had soon to learn that the cooling of tyres presented a difficult problem. Within their enclosed space, the maximum temperature permitted was soon reached, but problems of engine and gear cooling often counter balanced the advantages gained by streamlining.’

All these points have to be considered during tactical preparation for a race, and it is on the conclusions reached that the decisions must be taken whether pit stops are to be made or not. These matters are of first-rate importance. In fact, success in a race depends on them just as much as it depends on the tactics of the driver which were mentioned before in this article.

It can now be seen that a race is not just a haphazard competition between one car and other. Each circuit has its individual problems, and not least of these are the prevailing weather conditions. Above all, fuel, tyres, back axle and gear ratios must be adjusted according to the circumstances.

The particular suitability of individual drivers to different tracks has to be considered also and a strategical race plan cannot be worked out without continual observations of the other competitors and the tactics which they employ. There are supreme examples which prove that although complicated preparations were made for a race, it was a the result of such observations that victory was achieved.

There was an instance at the Nürburgring when a driver’s race plan required him to stop for one minute to change his tyre. However this driver had a ten-second victory over his rival whose plan permitted him to run through the ten lap race without a pit stop though at a limited speed.

This ” organisation for victory ” does not date back very far. Even in 1914 visual communication between driver and the pits did not exist. In those days the pits were really no more than depots for refuelling and the change of tyres, and it was not until the period between the two world wars that the pits became more and more ” the brains of the racing driver.”

After many years of practice, this “Organisation” no longer carries many difficulties in so far as circuits are concerned. What is not so easy to master is the “organisation” of long distance races such as the Mille Miglia. It was in 1931 that Caracciola arrived at the finish in Brescia and refused to believe his team manager when told that he had won the race. In fact, it was not until some half an hour later, when his victory was confirmed by the organisers of the event, that he was convinced. The Mille Miglia is so planned that although times between control points are given, they arrive so late that it is impossible to communicate them to a driver, who may be anywhere on the Appenine peninsula.

In this race the only workable maxim is: “Know the capabilities of your machine and your own ability and get the best out of both.” It was not without reason that the experienced Italian master Villoresi exclaimed after the last Mille Miglia:-” What a ghastly race ! ” Above all, in England, where there are many handicap races, ” the brains of the racing driver ” have a particular problem to solve. Here a driver is not in direct competition with his rival who holds a position in the race which is obvious to all. On the contrary, the pits must continually work out his position according to the class of his car.

Many times during the Tourist Trophies in Ireland the team manager has looked for his rivals amonst the fastest competitors whilst the real speed so far as he was concerned was dicated by relatively unimportant competitors who had completely escaped his notice. In each handicap race average comparative speeds are formulated. If a car in the small capacity class exceeds its handicap speed, then the driver of car in a larger capacity class is compelled not only to increase his relative speed but also the speed laid down by his class.

Many prominent drivers from the Continent have been baffled by this and have to do everything within their power not to be defeated by a completely unknown rival. What to an onlooker appears to be no more than the smooth running of a race is to the team manager the careful integration of many factors which achieves the much-sought-after victory.

* Radio communication was used successfully by the American Cadillac team at Le Mans last year – Ed

The Gigi Villoresi and Piero Cassani victorious, battered and bruised Ferrari 340 America Berlinetta passing through Bologna on its April, 29 1951 Mille run.

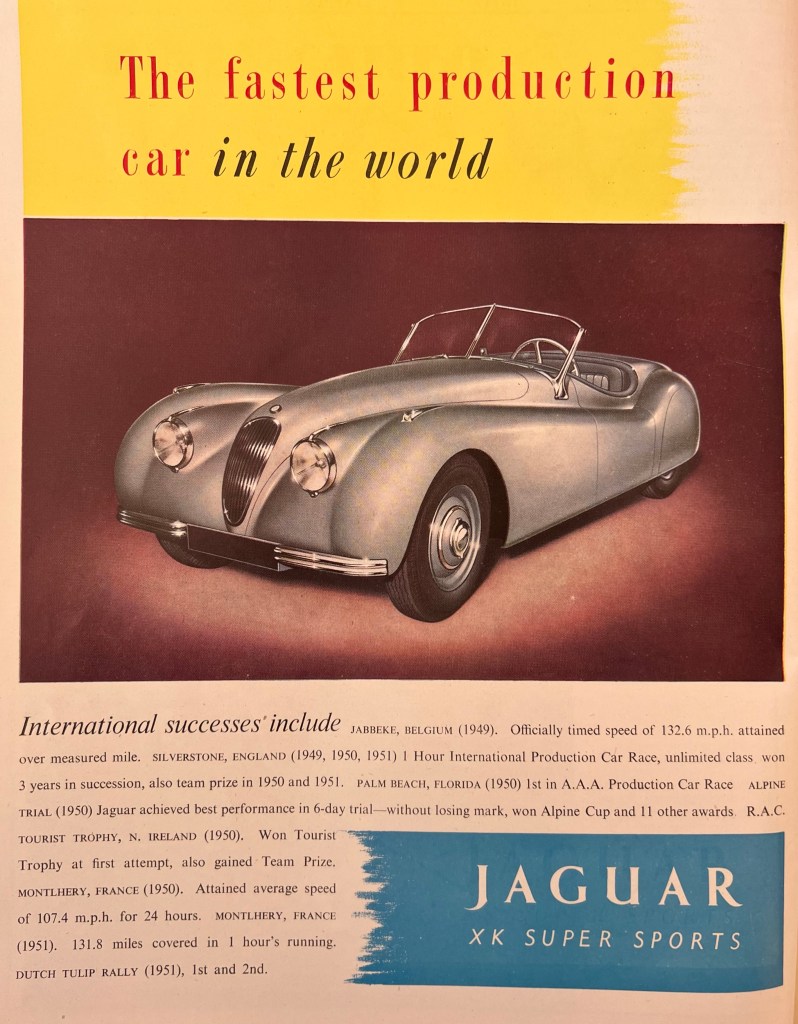

Jaguar XK Super Sports. Was that the car’s model name before XK120 came along or has the copy-writer goofed?

Credits…

Autocourse 1951 from Tony Johns’ collection – many thanks TJ

Tailpiece…

Finito…

Great article Mark … I never had a blomkqvist mom my ….. Jesuits wouldn’t allow it !

Sent from my iPhone

Mark, I have all books from 1976-77 (25th Anniversary Edition) through to last year’s edition (and am about to order the next edition) in my collection – the first brought back from GB by my parents. Wonderful publication, and has greatly assisted me in my Formula 1 ‘project’.

Mark, I have all books from 1976-77 (25th Anniversary Edition) through to last year’s edition (and am about to order the next edition) in my collection – the first brought back from GB by my parents. Wonderful publication, and has greatly assisted me in my Formula 1 ‘project’. Stuart