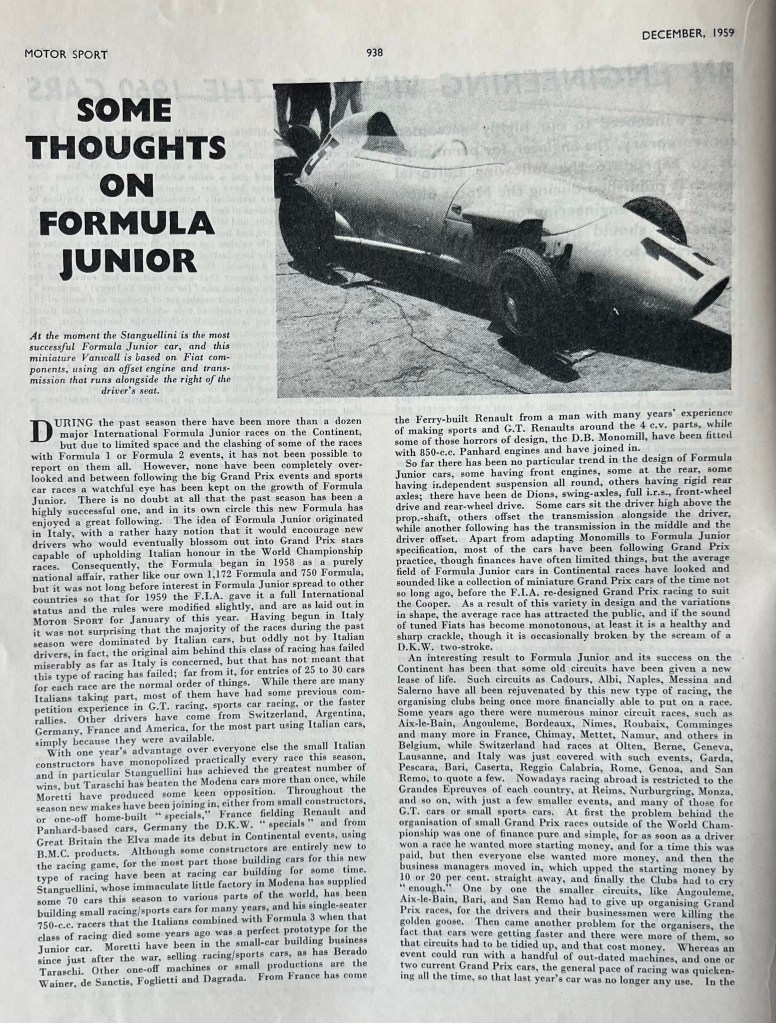

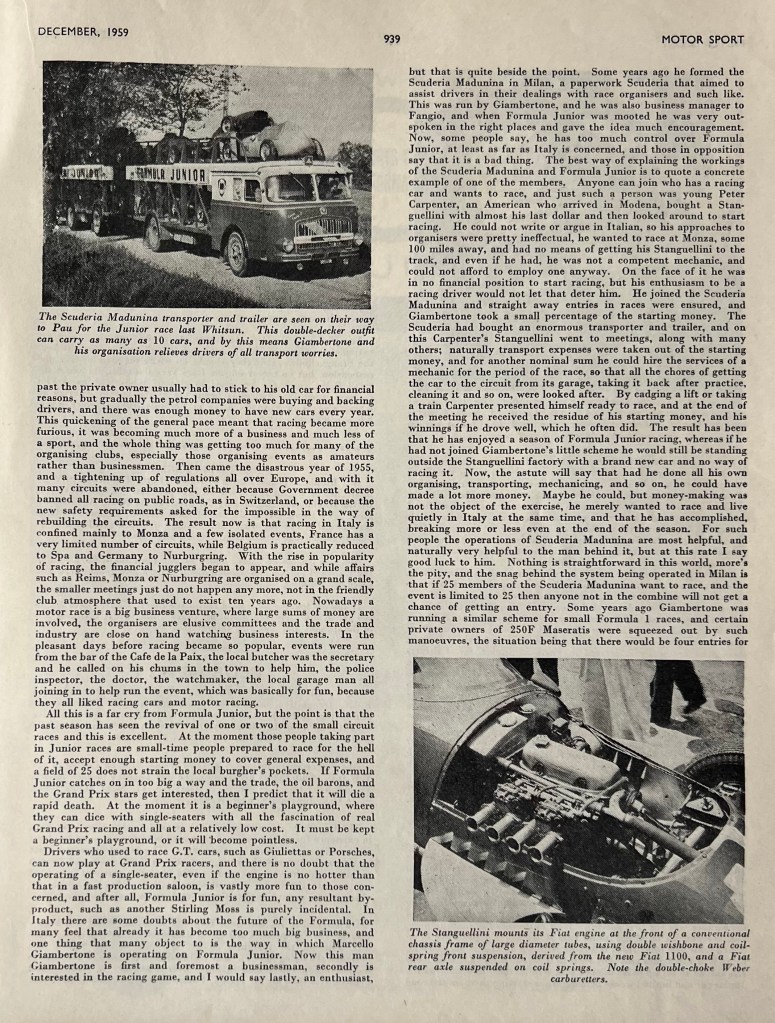

This piece by Denis Jenkinson caught my attention – the great man’s words always do – incredibly, by modern standards, the over 5,000 word feature has no photographic support whatsoever. It’s gold as a piece of in-period analysis…so I thought why not reproduce it in full with photographs.

Sylistically, it’s amazing, the longest paragraph is a staggering just over 700 words. DSJ isn’t a big fan of too many commas or full stops and there are no colons or semi-colons or fancy shit like that to be seen. At all. He explores all of his points in great detail using a less-is-more dicta throughout. It flows so well as a consequence…

While I have reproduced Jenkinson’s words and punctuation as was, I have added in a heading here and there to assist with your navigation having considered and rejected the use of photographs for that purpose.

Over to you, DSJ, hopefully he isn’t turning in his grave at the result!

In this article which I write every two years in MotorSport, I discuss the design trends in Grand Prix racing only, because it is in Formula 1 where designers and constructors have the freest hand unhampered by regulations.

As we know the Formula 1 is quite simple in limiting engine capacity to 2,500 c.c. without supercharger and 750 c.c. with supercharger, so that in all other respects the designer can make any decisions he likes. As things have turned out no one has made any serious attempt to build a supercharged 750 c.c. Grand Prix car and the supercharger and all its attendant complications and knowledge has died completely in racing circles. On the other hand the knowledge of getting power from an unblown engine has increased enormously and the science of carburetters and fuel injection has benefited.

Formula changes since the last review…

Since the last review in February, 1957, the Formula for Grand Prix racing has been slightly modified, in that the type of fuel to be used has now become specified by the F.I.A., whereas previously there were no restrictions. This freedom allowed experiments to be made with all manner of alcohol mixtures, and also with oxygen-bearing fuels such as nitro-methane. As the basis of engine power is a matter of how much oxygen can be burnt in a given cylinder and as this amount was limited to the amount of air that could be pumped into the cylinder, the principle of getting more oxygen in by using a fuel that carried its own was opening up some interesting new ideas, even though much of the chemistry of fuels was beyond a lot of engine designers and tuners, as was shown by the haphazard way in which nitro-methane was used by some people.

Since the beginning of 1958 Grand Prix engines have had to use a straight petrol of aviation category, rated at 130 octane, and the only reason for using this was a complete bungle on the part of the Commission Sportive International of the F.I.A. It was originally decreed that Grand Prix cars should use what the Paris congress described “pump fuel,” until someone asked them to define pump fuel and it was realised that no two pumps supplied the same fuel, and anyway, as Mr. Vandervell pointed out to the F.I.A., “the fuel that comes out of a pump depends on what you put in the tank.” A change of definition was made then to “100-octane petrol, as supplied to the public” but this was no good as a lot of European countries that intended to run Grand Prix races did not sell 100-octane petrol to the public. In desperation the F.I.A. searched about for some sort of straight petrol that was universal and available in all European countries, and of course, the only one they found was aviation petrol which was of 130 octane rating, so that was defined as the standard fuel for Grand Prix racing for 1958 and onwards.

Design and development in two parts…

In consequence of this we can look back upon the last two years of racing-car design as being in two distinct parts, even though there is a great deal of overlapping. In 1957 design and development had a free hand in everything except total cylinder capacity, and races were of 300 miles in length or ran for three hours, so that the conception of a Grand Prix car remained as in the previous Formula of 1947-53. As I have already written the year 1954 saw a reformation in Grand Prix car design, with many new ones and some really revolutionary ones, while the years 1955 and 1956 saw the development of the 1954 ideas, with a settling down of activities and a concentration on perfecting such as were available. As far as the British constructors were concerned 1957 saw a continuance of this long-term development, Italy produced new ideas as well as continuing with the old, France disappeared from the scene completely and Germany took no part. It saw the disappearance of Gordini from the Grand Prix field, after introducing his eight-cylinder car, and also Connaught, who though they lagged in engine design were well up on chassis design, and prepared to make interesting experiments in road-holding and also in aerodynamics as applied to racing-car bodywork.

Engines…

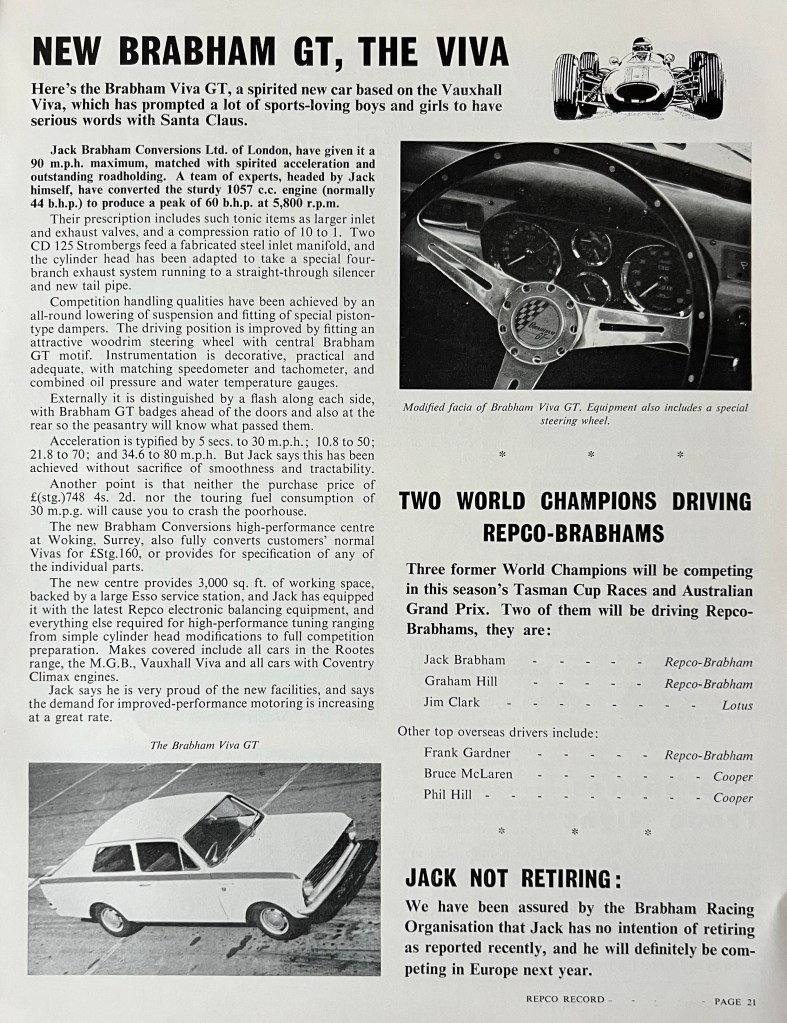

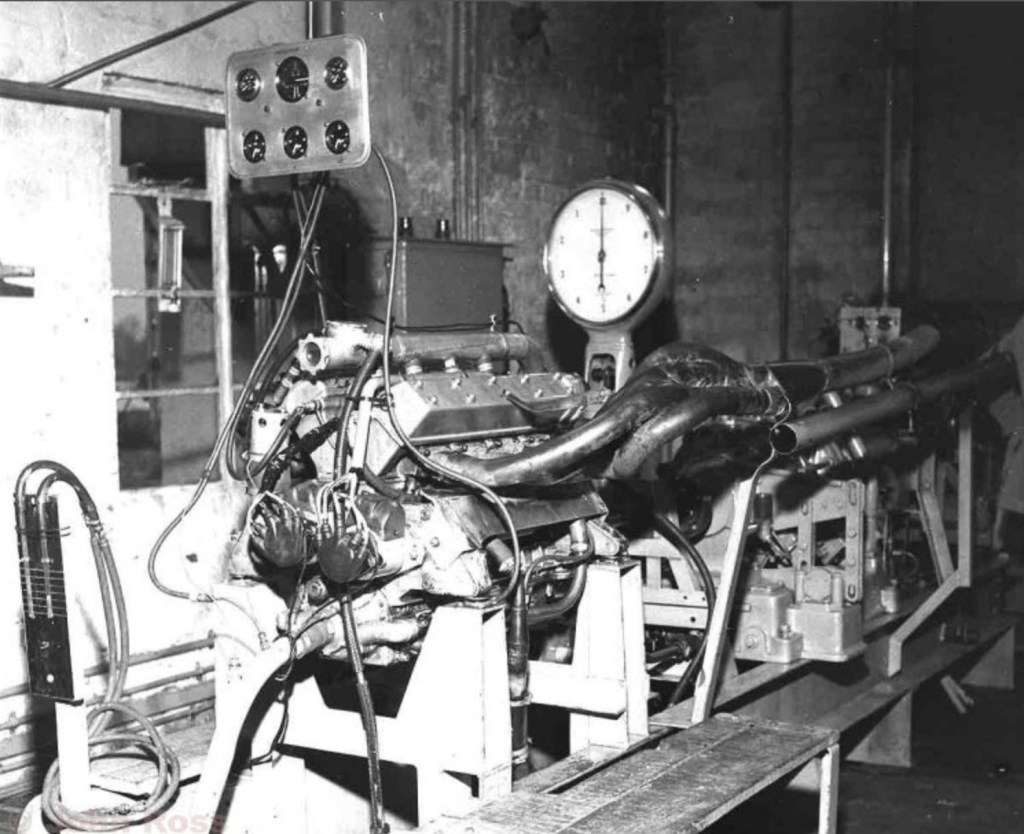

Taking the engine side of Grand Prix building first, as it is the engine which is really the heart of a racing car, we find that during 1957 Vandervell continued to develop his fuel-injection system on his four-cylinder engine and overcame many detail troubles connected with the installation. The actual mechanism of injecting the fuel into the ports caused very few problems on the Vanwall engine, the real difficulty being the control of this mechanism and practical installation problems such as the pump drive and mounting, piping operating rods, levers and joints. On power output the Vanwall was well up with its rivals, giving as much as 280 b.h.p. after using a small percentage of nitro-methane in the alcohol fuel mixture. It is interesting that all the Vanwall horsepower gain was achieved by mixture and combustion improvements, for the engine still turned at 7,400 r.p.m., retained the 96 by 86 mm. bore and stroke and two valves per cylinder.

The B.R.M. engineers followed a similar programme to Vanwall in that they continued with the same four-cylinder engine as they used in 1955 and 1956 and they remained on carburetters, failing to fulfill the promise of fuel-injection mooted when the car first appeared. As far as engine development went the B.R.M. did not make any startling advances and most of the time was spent on achieving reliability of such things as valves and timing gears, though in this quest for reliability the bottom end was completely redesigned from a four-bearing crankshaft to a five-bearing one. Engine r.p.m. remained down at 8,000 r.p.m. after the over-9,000 limit used in the very beginning, and though power increased slightly, to 270 b.h.p., there was little need to stretch things beyond this as the weight of the whole car was kept admirably low and a good torque curve was maintained, so that the increase in reliability provided B.R.M. with some measure of success.

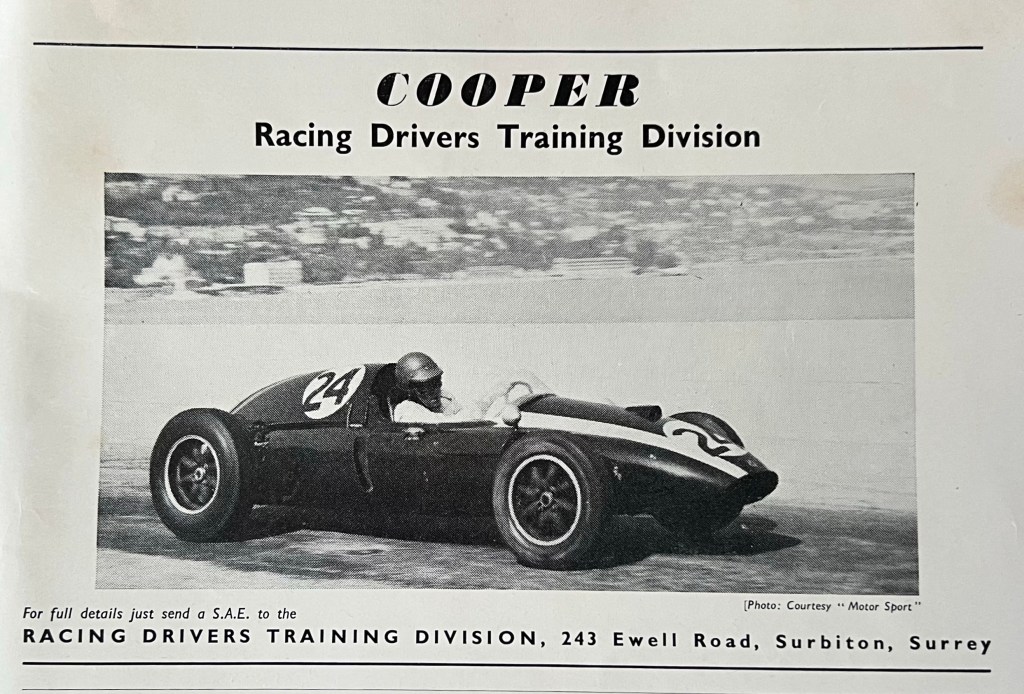

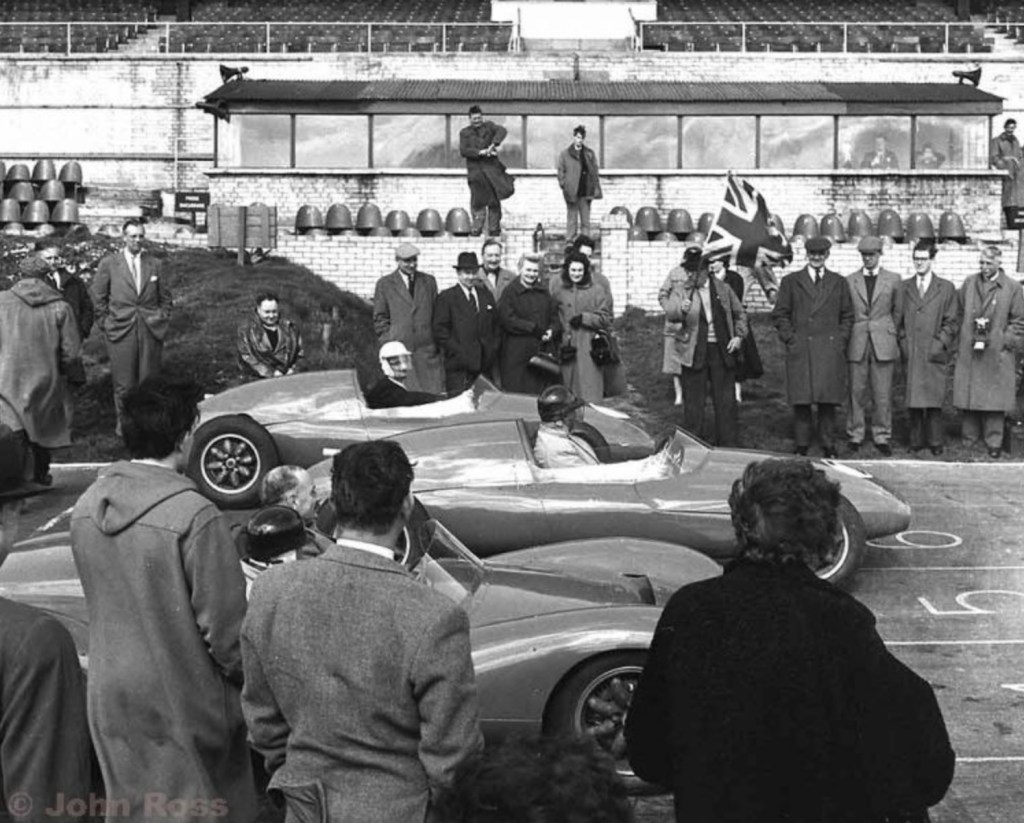

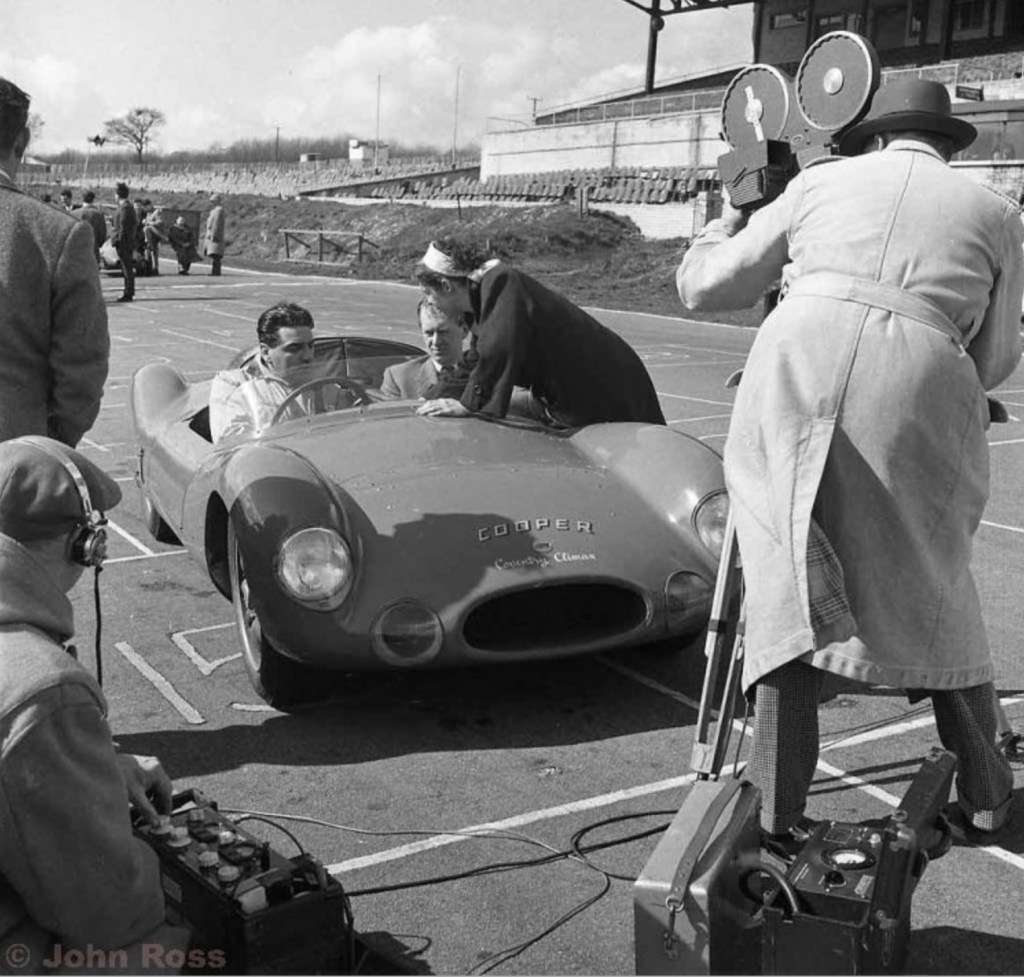

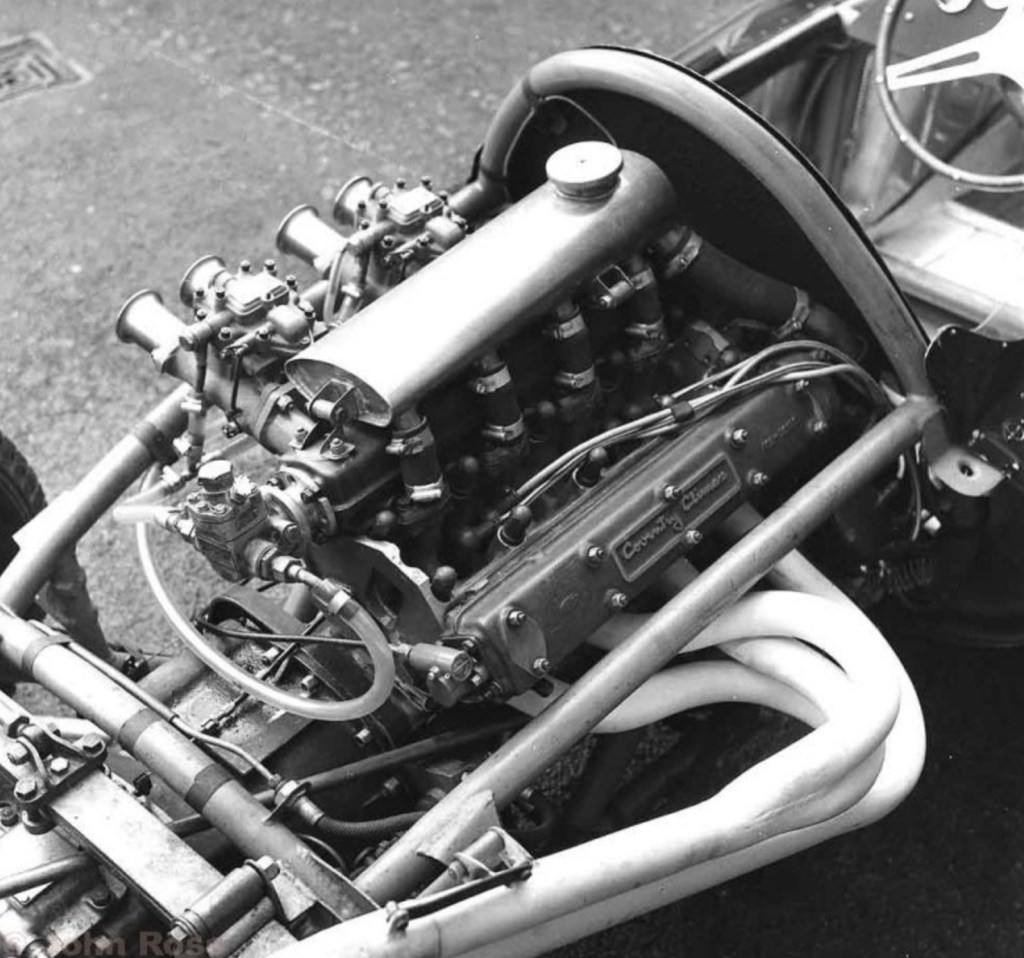

At the time that Connaught dropped out of Grand Prix racing a newcomer arrived from England in the shape of Cooper and in discussing engine development we must really overlook Cooper and deal with Coventry-Climax Ltd., the firm who designed and built the engines used in the Grand Prix Cooper cars. The four-cylinder FPF engine designed by Wally Nassan and Harry Munday for the Coventry-Climax engine-building firm was of necessity a compromise from the word ” go” and can hardly be allowed to influence any serious thoughts of Grand Prix engine design, even though its usage influences Grand Prix racing.

Originally conceived as a 1,500-c.c. engine for Formula 2 racing, which was introduced at the beginning of 1957, the FPF engine was contrived from pieces from the ill-fated 2,500-c.c. V8 Godiva engine built by the same firm. That engine was a complete failure for various reasons, and realising the need for an engine for Formula 2 racing Coventry-Climax used the cylinder head design from the Godiva and adapted it to a four-cylinder engine of 81.2 by 71.1 mm. bore and stroke. Being a commercial firm interested solely in selling engines, and having no direct connection with motor racing the FPF had to be designed and built to a definite price limit, unlike a pure Grand Prix engine, and in consequence it was sold as a 1,500-c.c. unit with a reasonable power output, but nothing phenomenal, nor was there anything particularly outstanding about the layout, having gear-driven twin-overhead camshafts and single sparking plugs to each cylinder, and using two double-choke carburetters.

Seeing the possibility of getting into Grand Prix racing by using his Formula 2 racing car John Cooper got together with R. R. C. Walker who was racing Cooper cars and between them they contrived to enlarge the FPF engine as much as possible in order to take advantage of the 2,500-c.c. engine limit. By increasing the bore until the cylinder walls were wafer thick, and making new crankshafts with a longer stroke the capacity was raised to 1,900 c.c. but the operation was in the nature of a bodge, rather than a piece of design, for this increased stroke necessitated fitting a quarter-inch aluminium plate on top of the block forming in effect a very thick gasket, in order to accommodate the increased travel of the pistons. At the bottom end the clearance between the piston and the crankshaft webs was such that any good engine designer would have curled up and died on the spot. The Walker equipe went even further and increased the bore even more until the cylinder walls were way beyond the reasonable safe limits of thinness and got the capacity out to 2,014 c.c. All this ” bodgery” worked up to a point, in a manner that has become the hall-mark of the Cooper firm, the point being that the engine was never able to produce anything like enough horsepower to make it a contender in a serious Grand Prix race, but at least it meant the addition of another manufacturer at a time when Connaught were on their way out.

Of all the British Grand Prix cars the Vanwall was undoubtedly the most successful and its power output was sufficient to allow the cars to win convincing victories in some of the faster races. Their real opposition came from Italy, to be more precise from Modena and Maranello, and during 1957 two entirely new and unhampered engine designs appeared, one from Maserati and the other from Ferrari.

From the Maserati drawing office, under the leadership of Alfieri, came a truly remarkable engine in the shape of a 2,500-c.c. twelve-cylinder in vee formation, with the two banks of six cylinders at an included angle of 60 degrees. With space restricted in the centre of the vee, there being two overhead camshafts to each bank, the inlet ports were arranged down through each cylinder head and special double-choke Weber carburetters were used to give one choke per cylinder. This arrangement of inlet ports running down past the plugs was unusual but not new, having been used by Mercedes-Benz on the W196 engine, and by B.M.W. before that. The Maserati engine used a bore and stroke of 68.5 by 56 mm., and this very short stroke allowed for high r.p.m. with 10,000 often being used. With such high speeds in use ignition was a problem, the orthodox magneto being unable to withstand the speeds and deliver sufficient sparks to the 24 plugs, there being two to each cylinder. A high voltage coil and distributor system was used, with a 12 contact distributor driven off each inlet camshaft and 24 separate coils mounted on the scuttle, current being supplied by a battery carried in the cockpit. Revs and power were no problem to this new engine, nor was the reliability factor lacking, but as B.R.M. had found back in 1950-53 such high revolutions with a limited power range proved very difficult for the driver to control. Although Maserati used a five-speed gearbox the car was always suffering from the r.p.m. dropping below 6,000 at which there was little torque. Without the use of extra special fuels this engine developed over 300 b.h.p. and had it been used with a six- or eight-speed gearbox it might have proved successful. However, after a whole season of development, during which time it proved remarkably reliable, but not very practical, the project was shelved due to Maserati giving up factory racing participation.

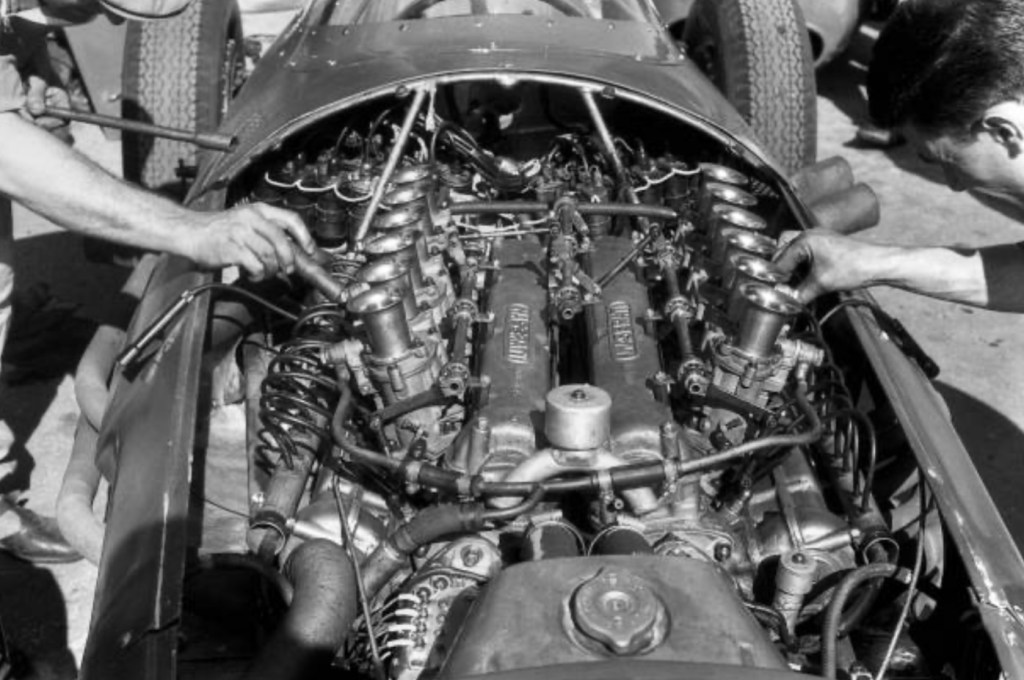

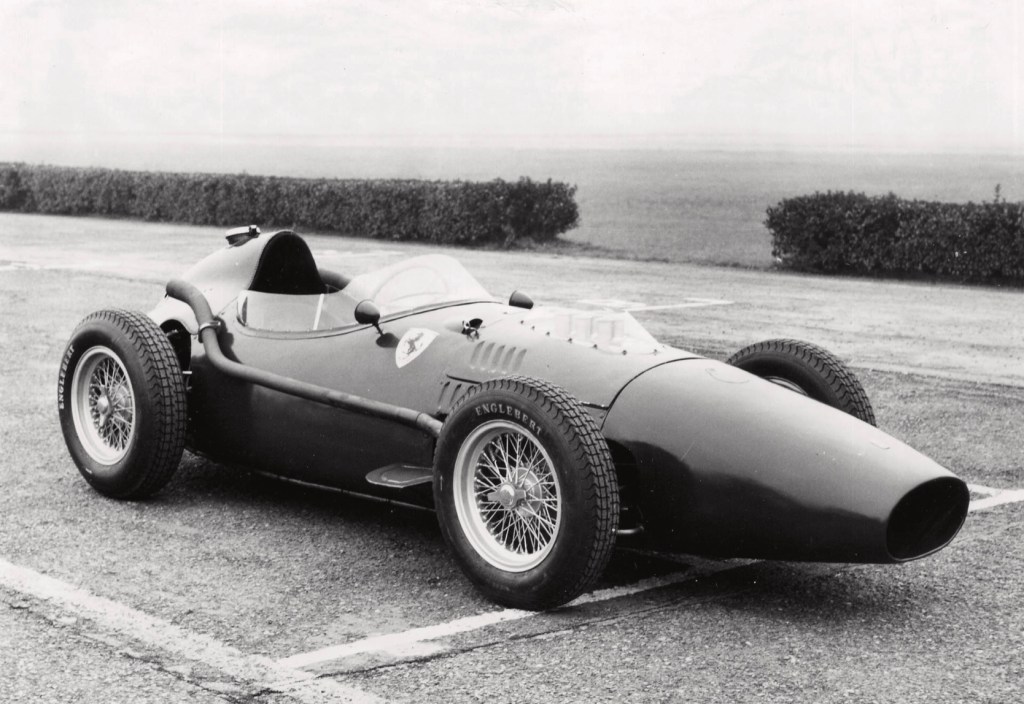

The other new engine to come from Italy emanated from that genius of design inspiration, Enzo Ferrari, though much of the idea for this new engine came from his son Dino Ferrari, who was to die from an illness before the new engine was really under way. In memory of his son, Enzo Ferrari named the new engine the Dino and it was originally built as a 1,500 c.c. Formula 2 unit, but the basic design was such that it was eventually enlarged to a full 2.5-litres and used for a new Formula 1 Grand Prix car. This engine was a 65-degree vee six-cylinder, the two blocks of three cylinders being staggered relative to one another, with the left-hand block slightly ahead of the right-hand one on the crankcase. Whereas the new Maserati vee engine had driven the four camshafts and all the accessories by a vast train of straight cut gears, the Dino Ferrari engine used roller chains to drive its four camshafts; three down-draught double-choke Weber carburetters were mounted in the vee of the engine. As a Formula 2 engine, with a bore and stroke of 70 by 64.5 mm. it was specifically designed to run on straight petrol of 100-octane rating and used a 9.5 to l compression ratio and 9,000 r.p.m. At the end of 1957 this design was enlarged to 2,417 c.c. by increasing the bore and stroke to 85 by 71 mm. and with the compression lowered to 8.8 to l and the r.p.m. dropped to 8,300 it still ran on straight petrol. Consequently when the 1958 season began the Dino engine was all set to race under the modified Formula. By the end of a season of development it was producing nearly 290 b.h.p. and was quite safe at 9,400 r.p.m., a figure quite often used by the drivers in the heat of the battle, even though 8,500 r.p.m. was given as a rev-limit. This new Ferrari engine replaced the Lancia V8 engine that the Scuderia had been using during 1957, for it had reached the end of its development after four years of hard usage.

In the two years under review these two Italian engines were the only two new designs to appear, and while of completely opposing views they had in common such things as four overhead camshafts, two plugs per cylinder, two valves per cylinder and a high r.p.m. range for maximum power and had carburation by Weber instruments specially designed for each particular engine.

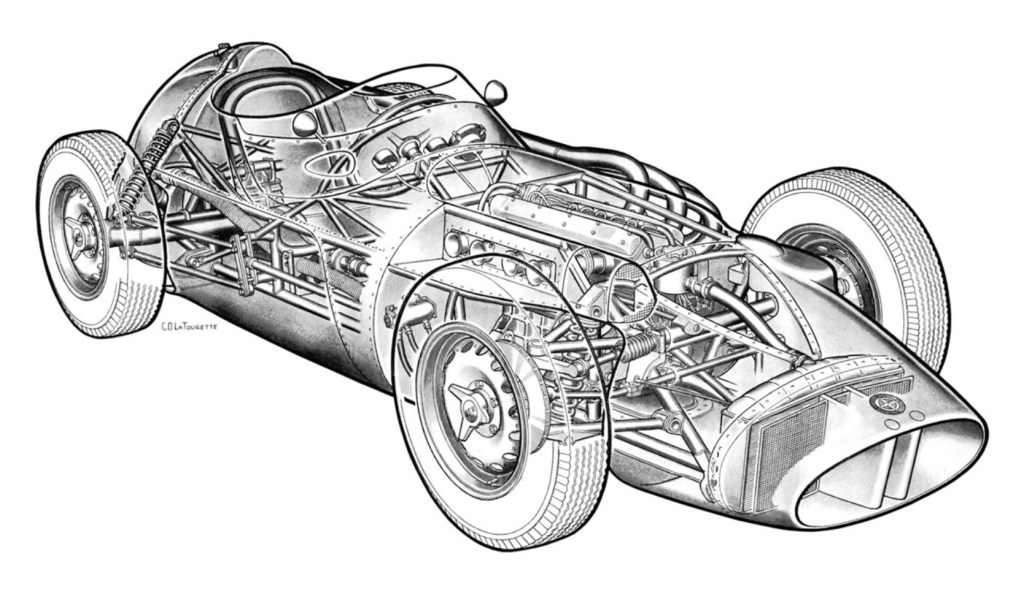

With the 130-octane ruling in 1958 one might have expected engine design to change, but such short notice was given of the fuel regulation that Vanwall, B.R.M. and Maserati could do little except adapt their existing engines. Cooper had to rely on whatever engine development work was being done by Coventry-Climax, and they were joined by Lotus in the Formula 1 field, who also relied on the Coventry firm for their power unit. Ferrari was the only one who was able to take advantage of the new fuel regulation and had no trouble as his engine had never used anything else but straight petrol. As Maserati had given up racing officially they did not bother too much about converting their trusty 250F six-cylinder to run on aviation petrol, and for the first race they merely recommended a change of jets to their customers, not even bothering to lower the compression ratio. The surprising thing was that the Maserati engine responded to this treatment and went on working throughout the season with no drastic alterations, though later the factory built some new engines with modified cylinder heads. This fact rather indicated that in 1957 they were either not taking full advantage of the alcohol/nitro-methane mixture they were using, the engine was running too cool, or that 130-aviation spirit was able to produce as much power as alcohol. This latter suggestion, coupled with different working temperatures, seemed to be the keynote of Grand Prix engines in 1958 for Vanwall found their power output still around the 270 b.h.p. mark, as did B.R.M., but working temperatures had gone up by as much as 200 degrees at the exhaust valves so that getting the Vanwall and the B.R.M. engines to run on straight petrol was not so much a problem of thermo-dynamics and combustion as one of metallurgy. Coventry-Climax made little advance in 1958 the unit being used in Formula 1 still being the mechanical “bodge” that had been perpetrated in 1957, though it did prove surprisingly successful as a result of unreliability in the more advanced designs. With Lotus taking part in Grand Prix racing it was not surprising that some new ideas were forthcoming and Chapman designed an intriguing new car with the engine canted over to lie almost horizontal. This meant a few modifications being made to the FPF unit in respect of oil collection, but it is interesting that drainage of the valve gear was no problem for the cylinder head had been originally designed to run in a canted-over position on the Godiva V8. The main problem involved was that of carburation, for they had to use an existing Weber horizontal double-choke instrument for each pair of cylinders, and within the space limitations under the bonnet the only possible shape of inlet manifold caused a considerable power loss, which they could ill-afford.

One cannot help feeling that had Lotus been based in Italy they could have got the help of the Weber carburetter firm who would have designed suitable carburetters for the engine layout, probably of the semi-downdraught type as used on the vee-12 Maserati. Throughout the whole period of unsupercharged racing engine design, it has been noteworthy that Alfa-Romeo, Ferrari, Maserati and O.S.C.A. have been able to work in close co-operation with Weber and have special carburetters designed specifically for an individual engine, whereas British engine designers have had to adapt an existing instrument if using Weber. The only co-operation in England has been from the S.U. Company, who designed new double-choke instruments to fit the standard Coventry-Climax FPF unit. Because of his inability to solve the power loss through the altered inlet manifold Chapman had to abandon his horizontal engine position and return to one of near vertical. In passing it is interesting that some years ago when Moto-Guzzi were dominating motor-cycle racing with their 250-c.c., 350-c.c. and 500-c.c. single-cylinder machines with horizontal cylinder layout, Norton Motors experimented with the same idea, turning the renowned Manx Norton engine through 90 degrees, but the idea was abandoned because they could never overcome the carburation problems.

Over the past two years we can sum up the engine design trend briefly by saying that Britain has shown no trend, except the further development of old designs, while Italy has tried two completely new units, one successful and one not so much so. As has been the case for many years, even back in the 1920s, the limit of power production for a given type of engine has seldom been one of design knowledge, but has been a question of metallurgy and being able to build the engines to withstand the designed power production.

Gearboxes…

Before turning to chassis design, which includes the basic frame itself, suspension units and the road-holding qualities, we might look briefly into gearboxes.

We find that Vanwall, and B.R.M. have made no changes at all, while Maserati merely developed their existing gearbox, to make all five speeds usable all the time, instead of first gear being merely for starting from rest. Ferrari designed an entirely new gearbox for his Dino engine, but it was in reality a scaled-down version of the Lancia D50 box, mounted to one side of the differential and having the clutch incorporated in it, between the bevel gears which turn the propshaft drive at right angles, and the box itself. Unlike most people, Ferrari decided that four speeds would be sufficient for his new gearbox. Cooper continued to use an adaptation of the Citroën four-speed unit, though for 1958 it was completely reworked, made stronger and used all Cooper-manufactured parts.

The only other new gearbox to appear in Grand Prix Racing was from Lotus, this being a constant-mesh five-speed unit mounted in one with the final drive and differential housing, and appeared in 1957 in the Lotus Formula 2 car, and in 1958 in the Formula 1 version. This gearbox is remarkable in its compactness and light weight, there being five pairs of gears mounted very close together, each pair continually in mesh and the drive from the engine is locked to any one of the bottom five gears at choice, by a sliding locking mechanism that travels through the hollow centres of the gears. Chapman has added to this design by trying two types of gear-change mechanism, one a positive-stop arrangement where the lever is always in the same position and a movement one way or the other effects a change up or down, as desired; the other arrangement was still positive-stop but had a progressive lever position, the short lever travelling along a slotted guide from first to fifth gears.

Chassis and Suspension…

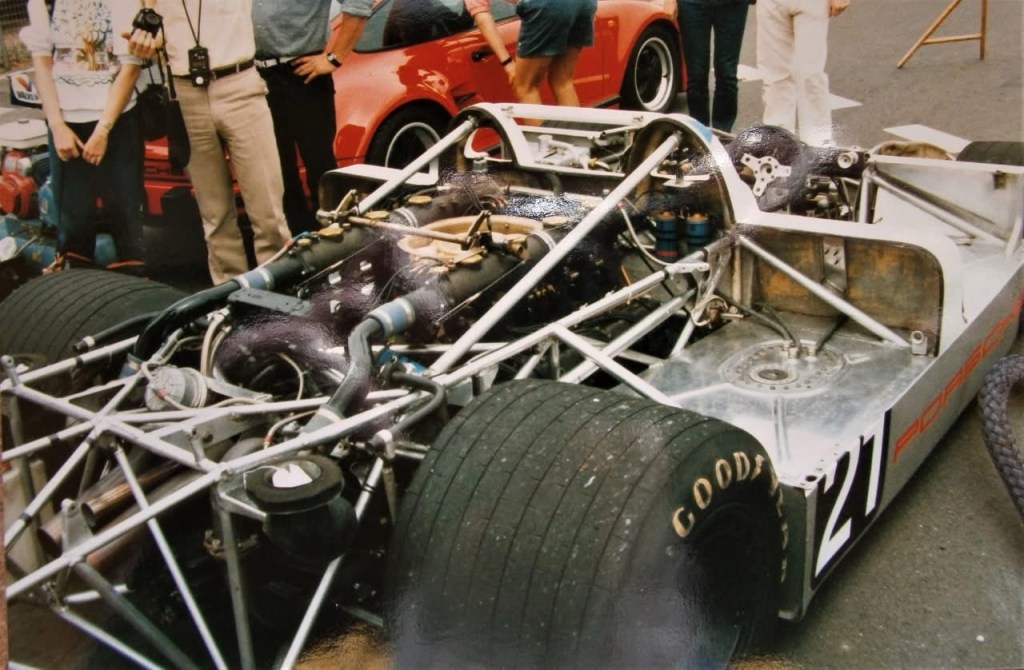

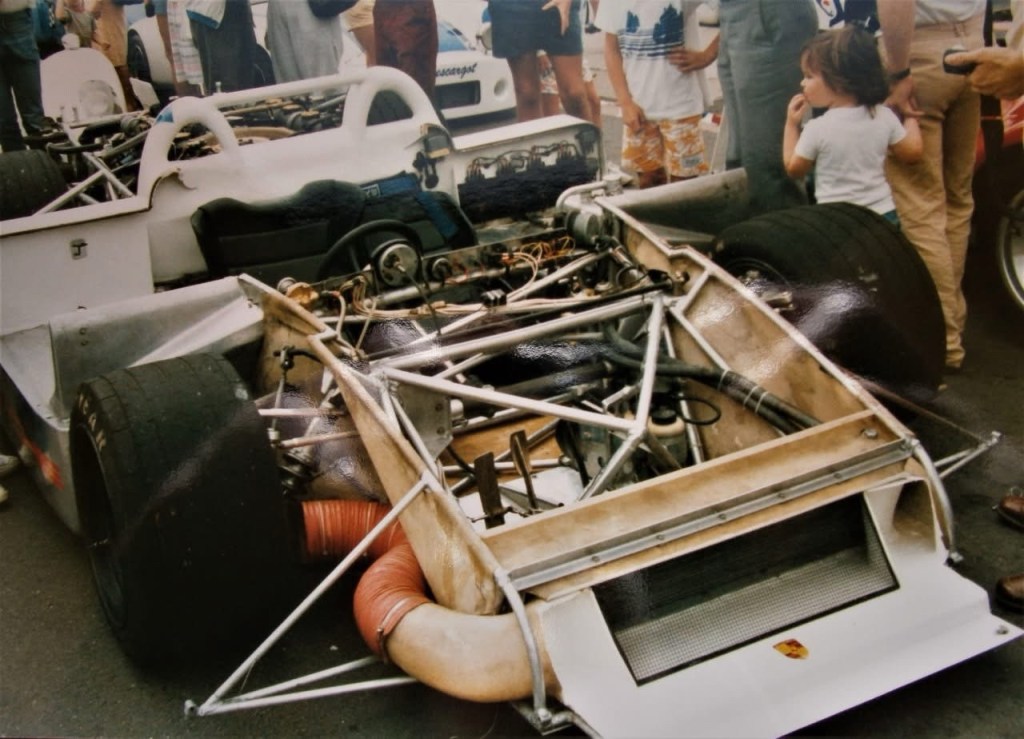

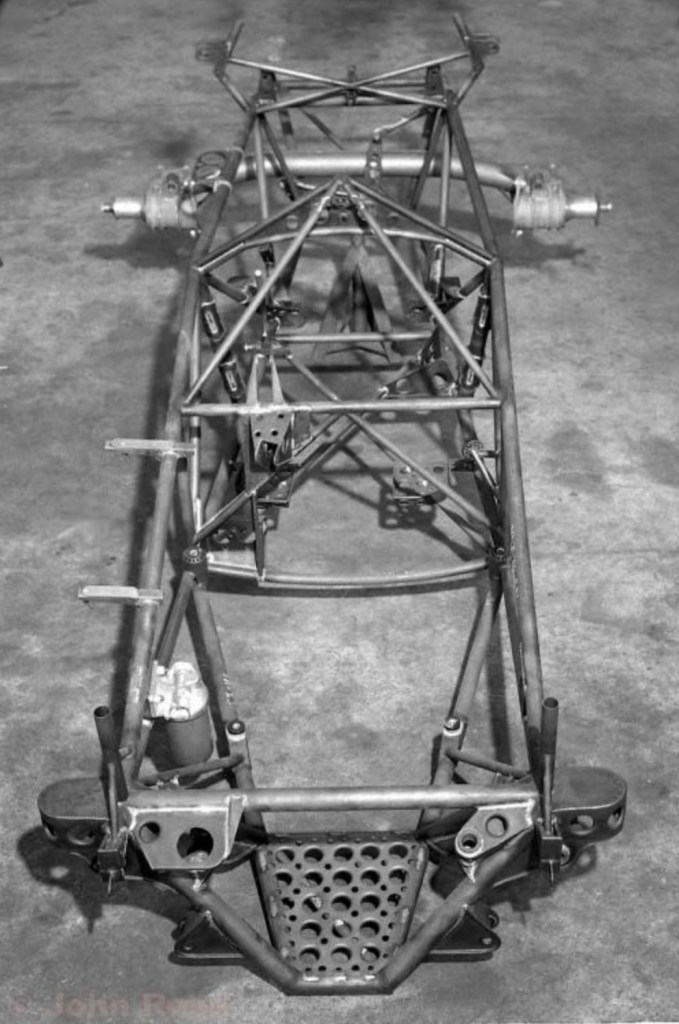

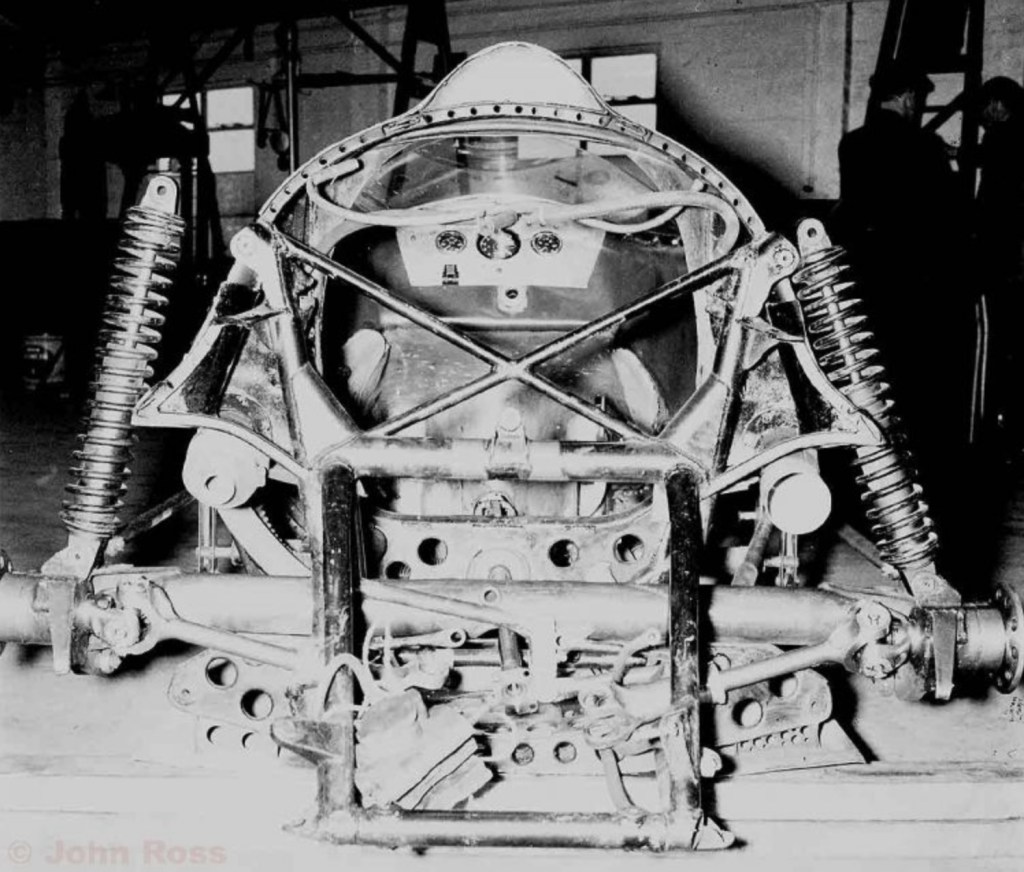

In the realm of chassis and suspension design it has again been Colin Chapman who has provided the new ideas, on his own Lotus cars, and in consultation with B.R.M. and Vanwall. One thing that is significant is that space-frames are now universal, except that Ferrari went from a full space-frame on his Formula 2 car to a semi-space-frame on his Dino Formula 1car.

Vanwall remained unchanged, being set with a near-perfect design for the car in question, while B.R.M. changed to a fully-stressed space-frame of Chapman inspiration and naturally both Formula 1 and Formula 2 Lotus cars have the acme of lightweight space-frames.

Cooper employs the general principles, but still fails to carry them through to finality, relying on heavy gauge tubing to impart strength and continuing to use curved tubes which are anathema to the space-frame designer. Maserati built new chassis frames in 1957 and again in 1958 and both times took a decided step forward in space-frame design, the layout being reasonable and diameter and gauge of tubing getting positively daring for Modena designers, who have long been reluctant to contemplate anything under 12 or 14 s.w.g. tubing.

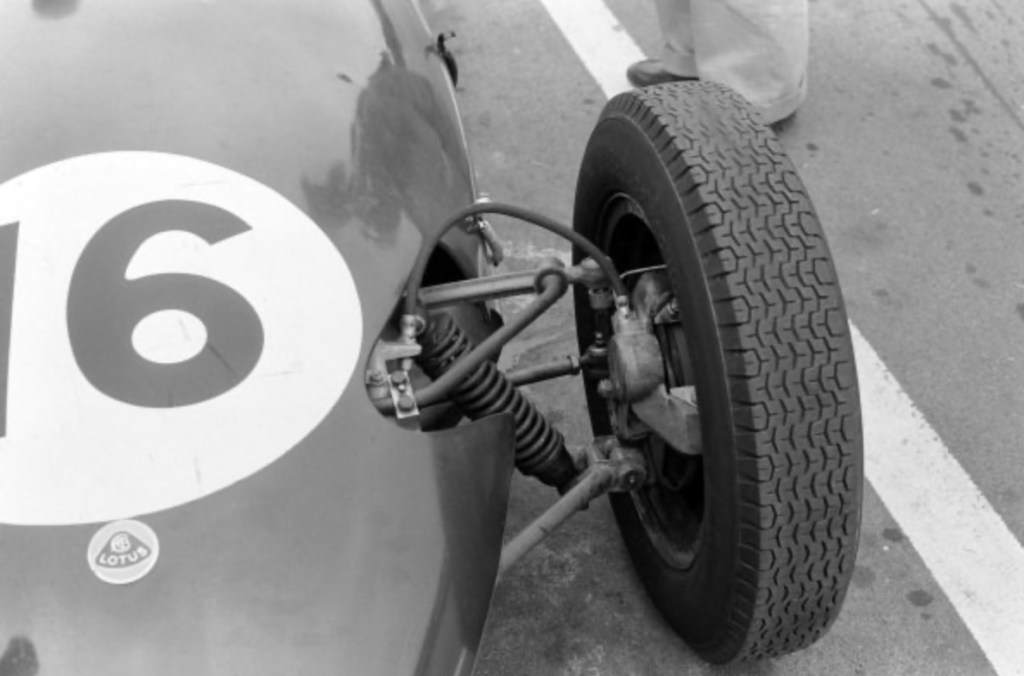

As regards front suspension there is now universal agreement in the double-wishbone and interspersed coil-spring layout, though the execution varies. Last to join this school of thought was Cooper who introduced it for his 1958 cars. Vandervell still uses beautifully machined forgings for his wishbones, as did Maserati in 1957, though on the 1958 Modena car a welded tubular construction was used. B.R.M. also used welded tubular construction of particularly nice design, while Cooper uses a very simple tubular layout, as does Ferrari on the Dino. Once again it is Chapman who differs, for his top wishbone is formed by a tubular strut and the end of a torsion anti-roll bar, his top wishbone member thus doing two jobs. Coil springs with tubular telescopic shock-absorber in the centre are popular, but some people still prefer the Houdaille vane-type shock-absorbers.

At the rear coil springs are equally in favour with British designers, Vanwall, B.R.M. and Lotus using them, while Cooper remains faithful to the transverse leaf spring, as does Ferrari and Maserati, though the Maranello concern experimented with coil springs on one car. The bigger cars still adhere to a de Dion layout at the rear, Vanwall, B.R.M., Ferrari and Maserati all using variations on the theme, while the small cars as exemplified by Cooper and Lotus have independent rear suspension. While Vanwall and B.R.M. provide lateral location by a Watt-linkage, Ferrari and Maserati still using a sliding guide. B.R.M. and Maserati mount their de Dion tube ahead of the rear axle assembly, and Vanwall and Ferrari mount theirs behind. On one thing all four agree, and that is that fore and aft location is provided by two parallel radius rods at each end of the tube.

On rear suspension Chapman and Cooper diverge widely, though both are fully independent, the former having an ingenious layout in which the hub is positioned in three directions, one forwards and inwards by a radius arm, one completely inwards by the half-shaft which has two universal joints but no sliding spline, and the third by the coil-spring unit which provides upwards and inwards location. With the radius arm, the half-shaft and coil spring forming an equilateral triangle with the whe l hub at the apex, this suspension is a new approach and in consequence called for a new name, and was called the “Chapman Strut Principle.”

Cooper continues to use his transverse leaf spring and lower wishbone layout, which originates from back in 1945 when he built his first car using Fiat Topolino front suspension. Nowadays the Cooper rear end is a sound and solid affair, with elektron hub carrier, roll-free leaf-spring mounting and good lateral location. On some cars used in Formula l a second wishbone was mounted above the existing one on each side and the transverse leaf spring was coupled to the hub carrier by a free link, thus relieving the spring of braking and accelerating stresses.

Wheels…

As regards wheels the British have a very definite liking for the solid type of alloy wheel, while the Italians still retain the old-fashioned wire-spoke wheel of Rudge pattern. Vanwall made some interesting experiments with wheels, assisted by Lotus, in the search for reducing unsprung weight and designed alloy wheels for the front which were non-detachable, having the wheel races mounted in the wheel casting itself, the whole assembly being held on by a conventional single split-pinned stub axle nut. These alloy wheels were not a success as they shrouded the front brakes and prevented air flow round the brake discs so were replaced by the normal Rudge hub wire wheel. Later a new wheel was designed on the same principle as the alloy wheel, in having the races mounted in the wheel itself and doing away with the heavy splined hub. With Grand Prix races reduced to two hours’ duration and tyres showing marked improvement in wear capabilities there is little need for a k.o. hub at the front. Like Connaught in the past, Cooper and Lotus use bolt-on wheels at each end of their cars. Vanwall still retain k.o. hubs at the rear, the splined portion being shrunk into the alloy wheel. B.R.M. use Dunlop alloy disc wheels all round, with k.o. hubs, these being a standard Dunlop racing component.

Brakes…

On the question of brakes the British are unanimous in their agreement on the use of disc brakes, though how they are used and what type still vary greatly. Vanwall continue to use their own manufacture, made under Goodyear patents, with the rear ones mounted inboard; B.R.M. use Lockheed components, with a single unit at the rear, mounted on the back of the gearbox and braking through the final drive unit, while Cooper and Lotus both use proprietary Girling units, one mounted on each wheel back and front.

After struggling along with cast-iron drums of excellent design on the Lancia/Ferraris and again on the Dino Ferraris, the Maranello engineers then developed a bi-metal drum and finally succumbed to the British influence and experimented with Dunlop and Girling disc brakes on the Dino cars. Maserati took an interesting step backwards on braking, for after developing bigger and better alloy drum brakes with steel liners, for the 250F in 1957, they then built a much smaller and lighter car for 1958 and were able to use a design of alloy drum brake that they had discarded in 1956.

Experiments in fully streamlined bodywork still continue to appear, in particular at Reims, and in 1957 Vanwall produced a Grand Prix car with a fully enveloping front half, and with fairings over the rear wheels which blended into the tail. The car never had a proper test and development never proceeded, but in 1958, at Monza they tried a further idea, in having a fully enclosed cockpit. formed by a detachable Perspex bubble which clamped on top of the normal wrap-round windscreen. 1958 at Reims was left to the Walker equipe to try full streamlining, by fitting their Coopers with panelling that enclosed all four wheels and merged into the normal body, but the results were inconclusive and the project was abandoned after practice. The Italians realised after 1956 that streamlining and aerodynamics was not their forte.

Summing Up…

Summing up briefly, we can say that British Grand Prix designers fall into two categories, one consisting of Vanwall and B.R.M., who were prepared and able to design racing cars from scratch, and having done so carried on with long-term development programmes and the other consisting of Lotus and Cooper who have very limited capabilities and design their cars around a number of limited factors, but both are ready and willing to experiment as far as their facilities allow them to go.

While Vanwall and B.R.M. started the Formula with cars built in the light of past Grand Prix car designs, and with the modification in 1958 to two-hour races, they have had to continually strive to modify their cars down in the question of size and lightness, and in Italy Maserati have done likewise.

Cooper and Lotus, on the other hand, started in Grand Prix racing with a car designed for an entirely different type of event, and by good fortune the change in the Formula tended to sway in their direction so that only a very slight increase in size in 1958 made their cars much more suitable for the racing encouraged by the present Formula, which is in the nature of non-stop sprint-like events.

Ferrari stands alone in all this, in being the only constructor to start all over again, with a car that was a good compromise between the old Lancia/Ferrari, or such things as the Mercedes-Benz W196 or the original 250F Maserati, and the Formula 2 lightweights as exemplified by Cooper and Lotus. The result has been that the Dino Ferrari proved itself eminently suited to all Grand Prix circuits as far as its general character, size and robustness was concerned.

Because the F.I.A. deemed it wise to run Grand Prix cars on aviation petrol, and reduce race lengths to 200 miles, there has been a distinct trend towards building smaller and lighter Grand Prix cars and in consequence there has been a search for reducing the unsprung weight on the cars.

By a logical series of steps the design trend of today’s Grand Prix car is undergoing a radical change, for without the possibility of using wasteful alcohol, fuel consumption has improved from something like 4-5 m.p.g. to 9-10 m.p.g.; the shorter races have reduced the total carrying capacity required, this large reduction in weight has allowed smaller tyres and lighter suspension parts to be used, and a smaller overall car has permitted smaller and lighter brakes and the whole character of Grand Prix racing is changing from one where driver, mechanics, team-manager and designer all had to work as a unit, to one where each member of the team does his job and then sits back and watches the next man do his.

Not so long ago the driver depended on his mechanics to change tyres and refuel the car during a race, and they depended on the team manager to control them sensibly, while the designer stood by to see any flaws in the design of his car both from the driving angle and the pit-work angle. Now the design is finished, the mechanics prepare the car, the manager organises the entry for a given race and then they sit back and watch the driver drive his short, but of necessity, concentrated race.

With the new rule for Grand Prix racing introduced in 1958 that drivers should not change cars once the race has begun, there has been even less encouragement for team work. The result has been one of clashing individuals and although it has nothing to do with the trend of racing-car design, the Grand Prix picture has changed in recent years because of the trend of design, encouraged by small modifications to the Grand Prix Formula.-D. S. J.

Credits…

Denis Jenkinson, MotorSport February, 1959, LAT Images, C La Tourette, John Ross, Getty Images, Grand Prix Library

Tailpiece…

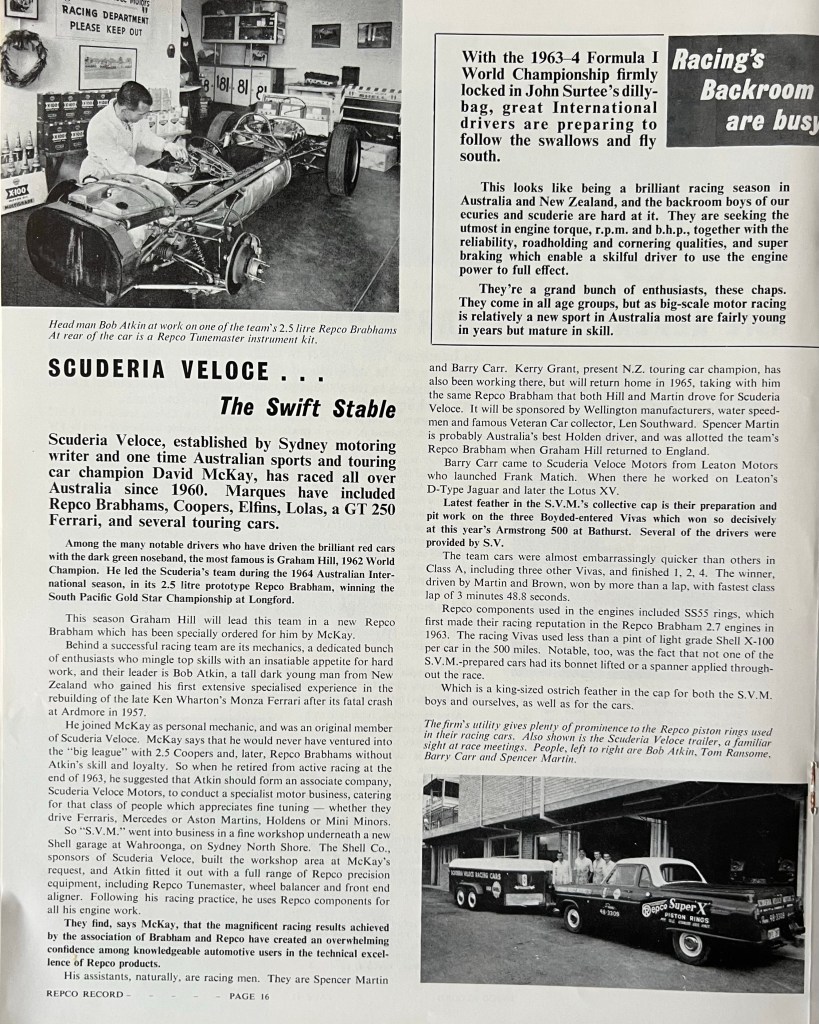

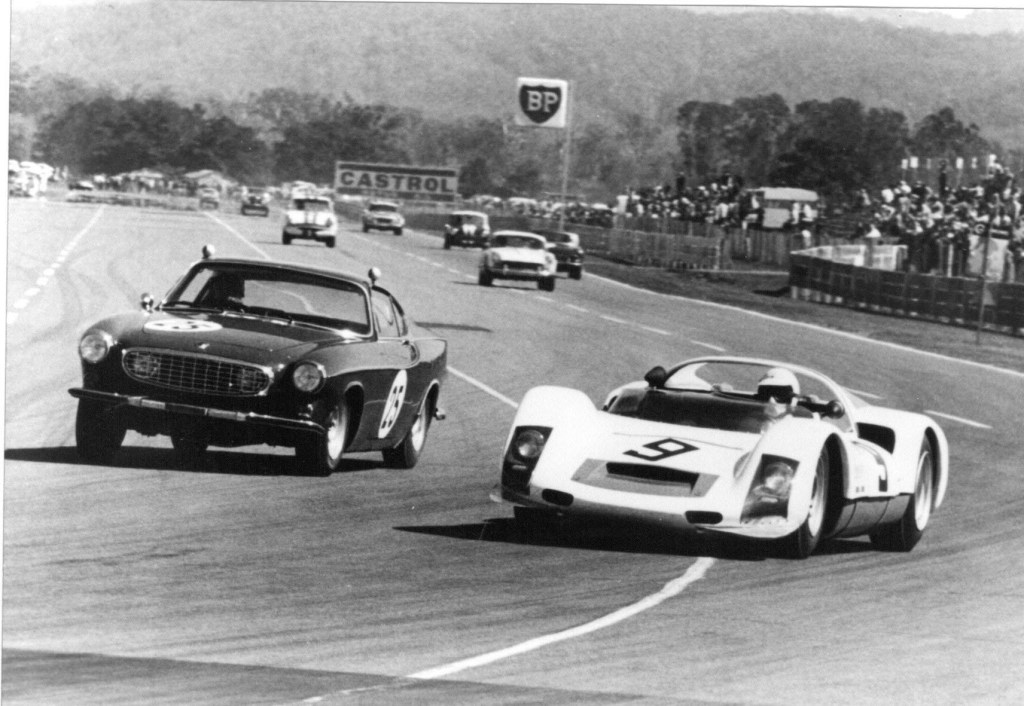

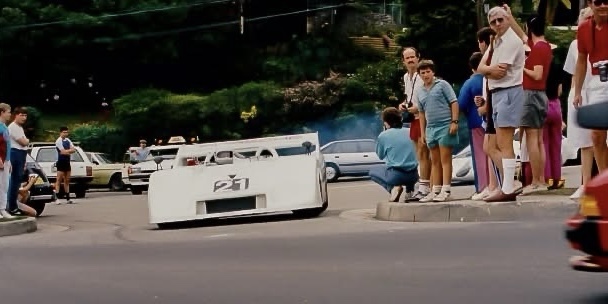

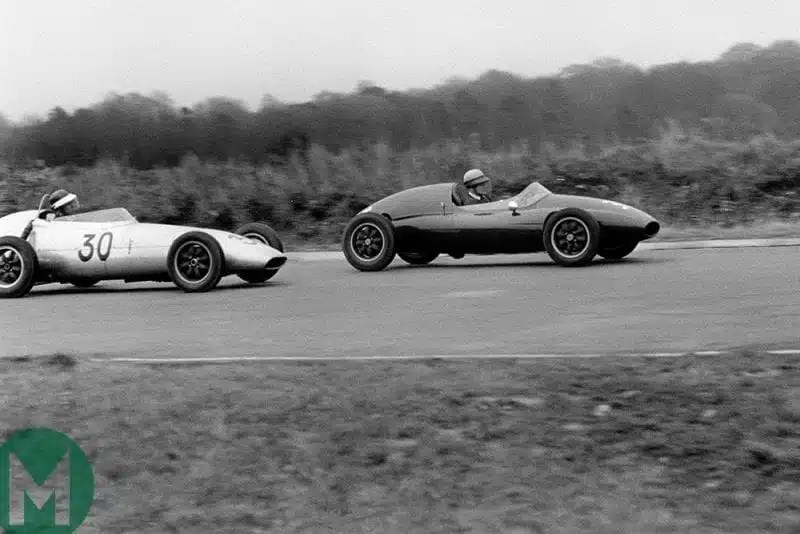

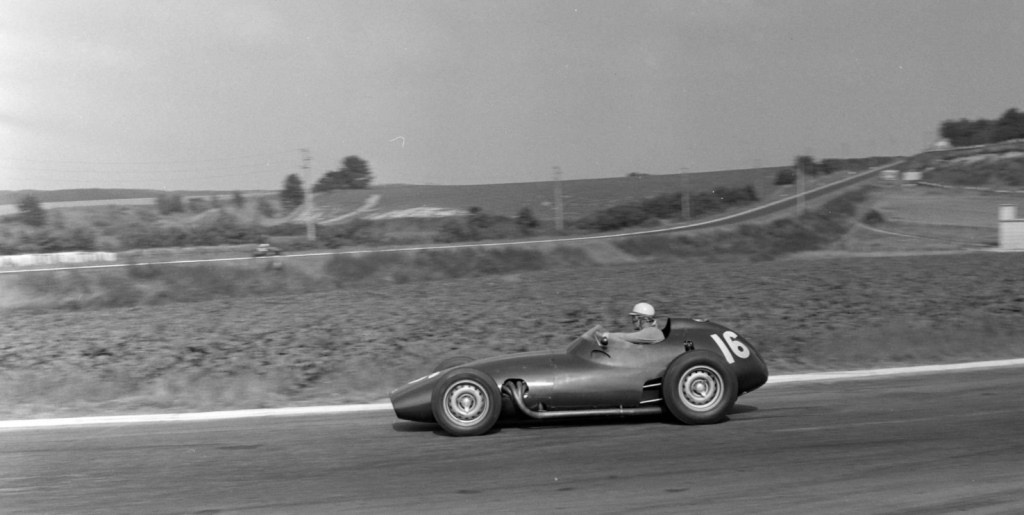

Not a Cooper to be seen in this shot at Ain Diab, Morocco on October 19, 1958.

It shows Olivier Gendebien’s Ferrari Dino 246 leading Harry Schell’s BRM Type 25 and Graham Hill’s Lotus 16 Climax in a mid-field Moroccan GP dice.

The Coopers would become rather more prominent in 1959…

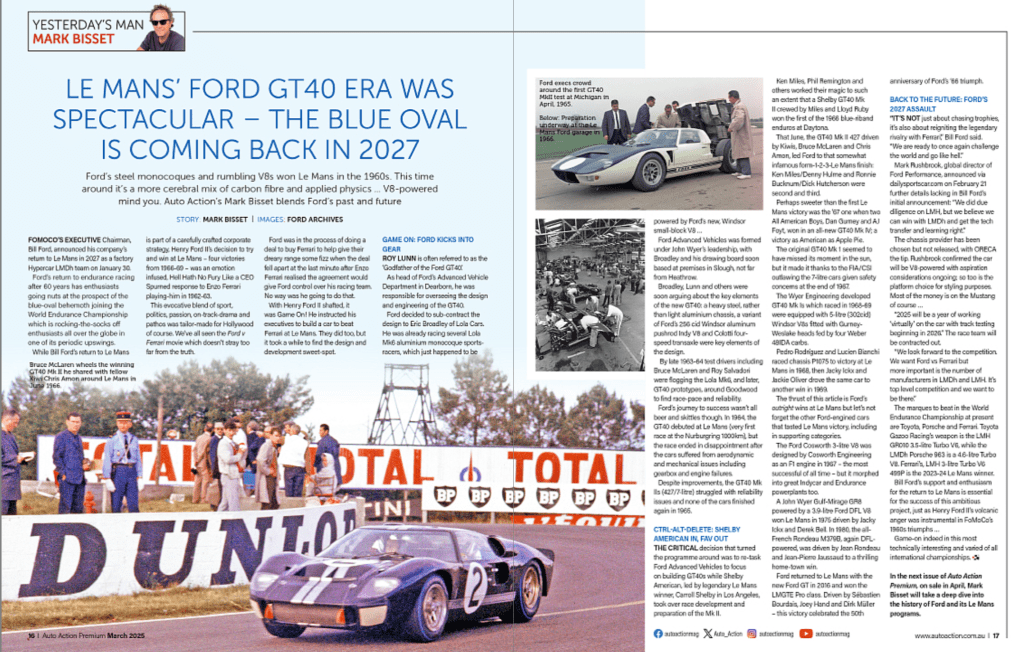

Finito…