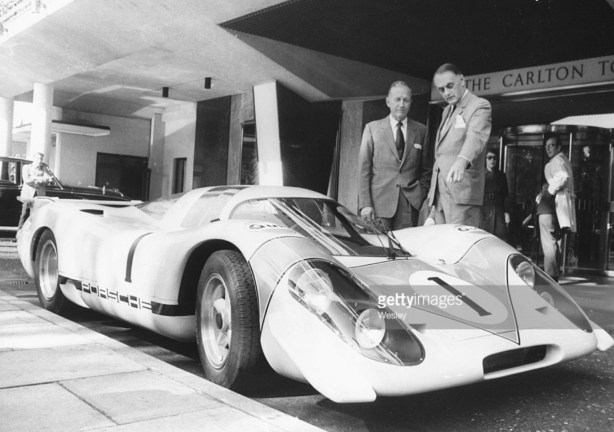

Ford GT40 chassis 101, the first of 12 prototypes built, on the runway at JFK Airport, New York, in early April 1964…

The machine is on its way to the New York International Auto Show, having been presented publicly to journalists in an open day at Slough, then outside the offices of Trans World Airlines at Heathrow on April Fools Day, before it was flown to the US “to be used for a press conference prior to the Mustang launch,” then display between April 4-12.

The car was a starlet for only the briefest of times, it was destroyed in an accident in the wet while being driven by Jo Schlesser during the Le Mans test weekend on April 18.

Ford’s blunt telex on May 22, 1963 announced the end of discussions of the takeover of Ferrari by the Detroit giant. “Ford Motor Company and Ferrari wish to indicate, with reference to recent reports of their negotiations toward a possible collaboration that such negotiations have been suspended by mutual agreement.”

A month later Ford created the High Performance and Special Models Operations Unit – catchy ‘innit? – to design and build a Le Mans winner. Members of that group included Roy Lunn and Carroll Shelby. Kar Kraft was established within FoMoCo to oversee the Ford GT program, with Lunn its manager.

They soon identified and contracted Eric Broadley as project engineer, his monocoque Lola Mk6 GT Ford, which had performed well at Le Mans in 1963, despite not finishing, was a ground-breaking sports-prototype. As part of the deal Ford acquired the two existing Lola GTs, giving them a nice head start. John Wyer was appointed as race manager, a role he had performed at Aston Martin when Shelby co-drove an Aston Martin DBR1 with Roy Salvadori to Le Mans victory in 1959.

“The four pronged team comprised Lunn and Broadley designing and building the cars, Wyer managed the operation with Shelby acting as frontman in Europe,” Ford wrote.

Key members of the Slough design team included Broadley, Lunn, Phil Remington and Len Bailey.

In the 10 months prior to the ’64 Le Mans classic the program got underway at Lola’s premises in Bromley. The Ford Advanced Vehicles (FAV) operation later moved to a factory in Slough, alongside Lola, who moved as well – in the middle of what is now referred to as Motorsport Valley – in the Thames Valley.

Some development work was carried out in Dearborn, but in essence the Ford GT40 was a British design funded by US dollars. The Ford contribution – most critically was absolute monetary and management commitment from the top to succeed – included engines and aero-modelling in which a scale model of the car was tested in their Maryland wind tunnel. Computer aided calculations related to aerodynamics under braking was undertaken and anti-dive geometry explored. The two Lola Mk6 Fords were used as mobile test-beds in the hands of Bruce McLaren and others until the end of 1963.

Let’s go back to the April 1964 logistics of #101. Ford GT40 anoraks shouldn’t get too excited by this piece, the words are a support for a bunch of great Ford Motor Company photos taken at JFK and in the studio I’ve not seen before. After the New York International Auto Show, the car retuned to the UK and was transported to the Motor Industry Research Association (MIRA) test track at Nuneaton where private shakedown tests took place.

The Le Mans test weekend followed on April 18-19. Jo Schlesser was allocated #101 and Roy Salvadori #102. Jo had already complained about high speed directional instability, when, on his eighth lap, he lost control in the wet at over 150mph. Miraculously, the car didn’t roll or hit trees, but it was destroyed with Schlesser copping only a minor cut to his face. Lady Luck was with him that day…not so at Rouen in 1968.

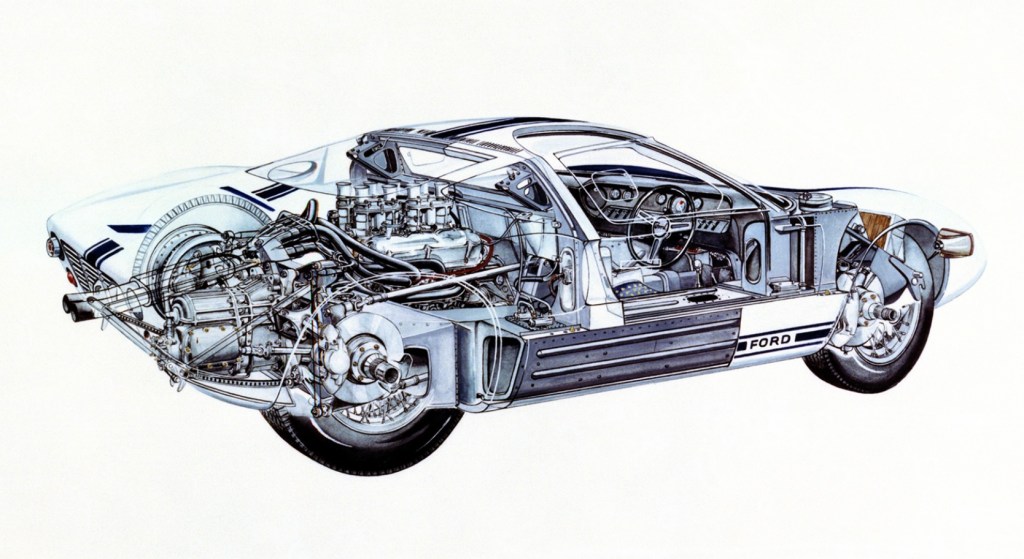

Chassis and Suspension…

The Abbey Panels built steel monocoque – Eric Broadley wanted aluminium, while Ford wanted steel – incorporated two square tube stiffeners that ran from the scuttle to the nose. At the rear was a lightweight detachable subframe which supported the engine and suspension. Each sill-panel housed a bag-type fuel tank. The car weighed circa 865kg.

Front suspension was period typical upper and lower wishbones and coil spring/ Armstrong damper units, and an adjustable roll bar, the uprights were made of magnesium alloy. There was nothing radical at the rear either. Again the uprights were mag-alloy, there were single top links, lower inverted wishbones, coil spring/dampers and two radius rods looking after fore-aft location, and an adjustable roll bar.

Brakes were 11.5 inch Girling rotors and calipers, while the wheels were heavy 15-inch Borrani wires, pretty naff by that stage given the modern technology used throughout the design; and addressed by Shelby American when they took over developmental charge of the race program from the end of 1964. The knock-off Borranis were 6.5-inches wide at the front and 8-inches up the back. ‘Boots’ were Dunlop R6s.

Engine and Transmission…

The engine was a Ford Windsor small-block, cast iron, pushrod 90 degree 255cid V8. With a bore-stroke of 95.5 x 72.9mm, the four 48IDA Weber fed 4183cc engine developed circa 350bhp @ 7200rpm and 299lb-ft of torque at 5200rpm using a compression ratio of 12.5:1.

Colotti provided their Type 37 four speed transaxle which incorporated a limited slip diff to get the power to the road via a Borg and Beck triple plate clutch. Gear ratios were of course to choice, with a top speed of 205mph quoted with Le Mans gearing.

Bodywork and Aerodynamics…

The GT40 name came about by picking up on the cars incredibly low height, two inches lower than than Broadley’s Lola Mk6.

Specialised Mouldings, a Lola supplier, based then in Upper Northwood, made the fibreglass bodies, the aerodynamics of which took much time to get right. Shelby ‘perfected’ the sensational, muscularly-erotic shape of the cars which won Le Mans in 1966-68-69 over the winter of 1964-65. The ’67 Mk4 being a different aerodynamic kettle-of-fish.

The headlights were fixed under clear Plexiglass covers with additional spotlights inboard of the brake ducts. Two big air intakes were sculpted into each flank to assist engine cooling with additional ducts on the panels each side of the rear screen.

At the rear were meshed cooling vents through which the raucous V8 exited its gasses. The body was slippery enough but not yet effective.

Driver ergonomics were very much to the fore. The top off each door was cut deeply into the roof. Once the driver cleared the wide-sill of the RHD, right-hand shift machine, he popped his arse into a light, fabric, perforated seat fixed in location; the pedals were adjustable.

I’m not sure if the 12 prototypes were built in this manner, but Denis Jenkinson described the GT40 production process in MotorSport as follows.

“The steel body chassis unit, made by Abbey Panels, of Coventry arrives in Slough in a bare unpainted form. Front and rear subframes are fitted, for carrying body panels etc, and then the unit goes to Harold Radford Ltd, where the fibreglass doors, rear-engine hatch which forms the complete tail, and front nosepiece, which is a single moulding, are cut-and-shut to fit the chassis/body unit, these panels then being marked and retained for the car in question. The fibreglass components are made by Glass Fibre Engineering of Farnham, Surrey and then delivered to Slough in the bare unpainted state. When the chassis/body unit is returned from Radfords the factory at Slough then assembles all the suspension parts, steering, wiring, engine, gearbox and so on, the final car being painted in the particular colour required by the customer.”

Checkout this evocative piece at Abbey Panels and Le Mans…

Many thanks for the tip-off Tony Turner!

1964 Season…

Given the lack of development time before the GT40 was raced, the initial races were pretty much a disaster.

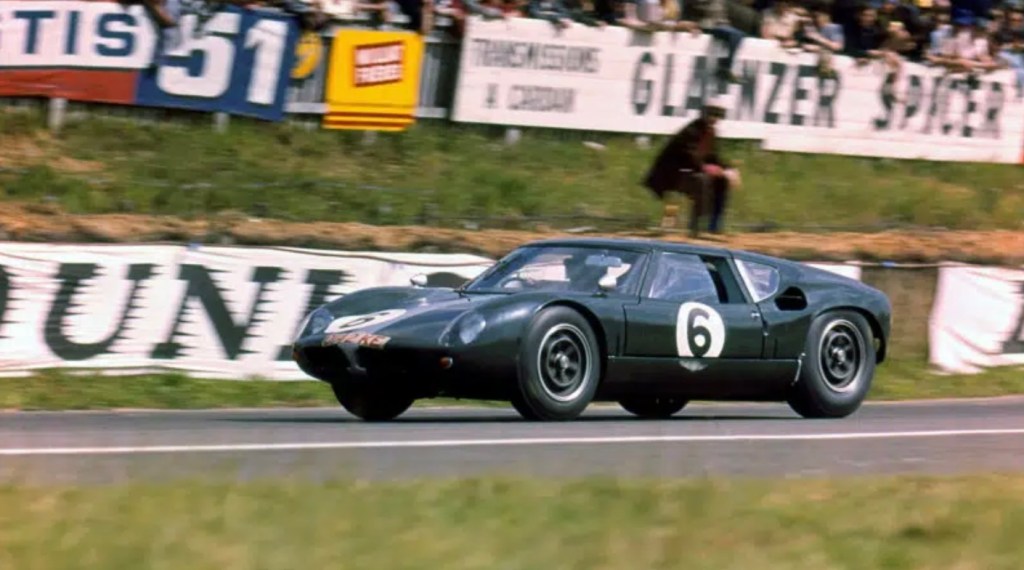

Ford lost #101 (Schlesser) during the Le Mans test, while Salvadori gave #102 a gentle run, they were 12th and 19th quickest.

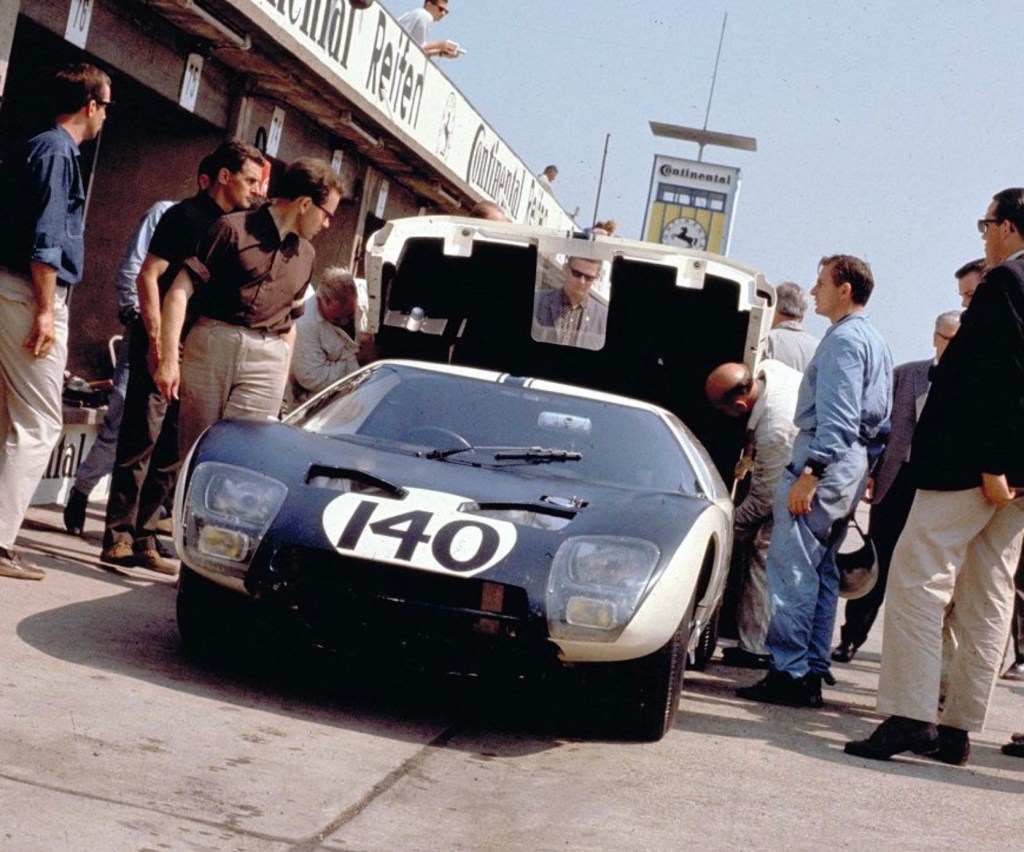

Six weeks later #102 contested the Nurburgring 1000km with a modified front clip manned by vastly experienced racer/engineers, Bruce McLaren and Phil Hill. Bruce was the lead test-driver on the GT40 programme. They qualified the car second behind the Ferrari 275P of John Surtees and Lorenzo Bandini. Phil ran between second and fourth in his stint but the car was retired with suspension damage early after Bruce took the wheel.

At Le Mans three cars were entered for Hill/McLaren, Richie Ginther/Masten Gregory and Richard Attwood/Schlesser. While Ford set a lap record, all three cars retired; the Attwood car caught fire, with both other cars retiring with gearbox failure.

The two cars that appeared at the Reims 12 Hours a fortnight after Le Mans were #102 and #103, plus a new car, #105, powered by Shelby prepared 289 V8 giving about 390bhp at a lower 6750rpm – 341lb-ft of torque was up too. New third-fourth selectors were fitted to the Colotti ‘boxes, and the dog-rings hardened. The Surtees/Bandini Ferrari 250LM started from pole, but by lap 10 the Ginther GT40 led McLaren. Richie’s lead ended with crown wheel and pinion failure on lap 34, Atwood’s with a plug that had come out of the gearbox, while the Hill/McLaren car blew its engine.

Chassis 103 and 104 were then raced in the Nassau Speed Week by Hill and McLaren fitted with 289 V8s (4.7-litres). Only Phil made it through the Nassau Tourist Trophy qualifier, Bruce had suspension problems in 104. Hill’s car suffered the same fate in the feature race.

Without a finisher in four meetings, chassis #103 and #104 were shipped to Shelby American in California. “The decision was made in Dearborn to move the (development) work back back to the US, with Carroll Shelby given operational control and Lunn engineering control.” Ford’s website records.

Over that autumn and winter an intensive development programme together with with FAV produced a race winner, not a Le Mans winner mind you, but that would come soon enough…

And what happened to #101 you ask?…

The car’s odometer recorded only 465 miles at the time of its death. It was written off with many parts salvaged…the monocoque may have been repaired and renumbered. Ford has never released the details of what became of the various components, not least the all-important chassis. There is a replica of course, no point letting a vacant chassis number go to waste, it won an award at Pebble Beach, so I guess it’s a very shiny one.

Etcetera…

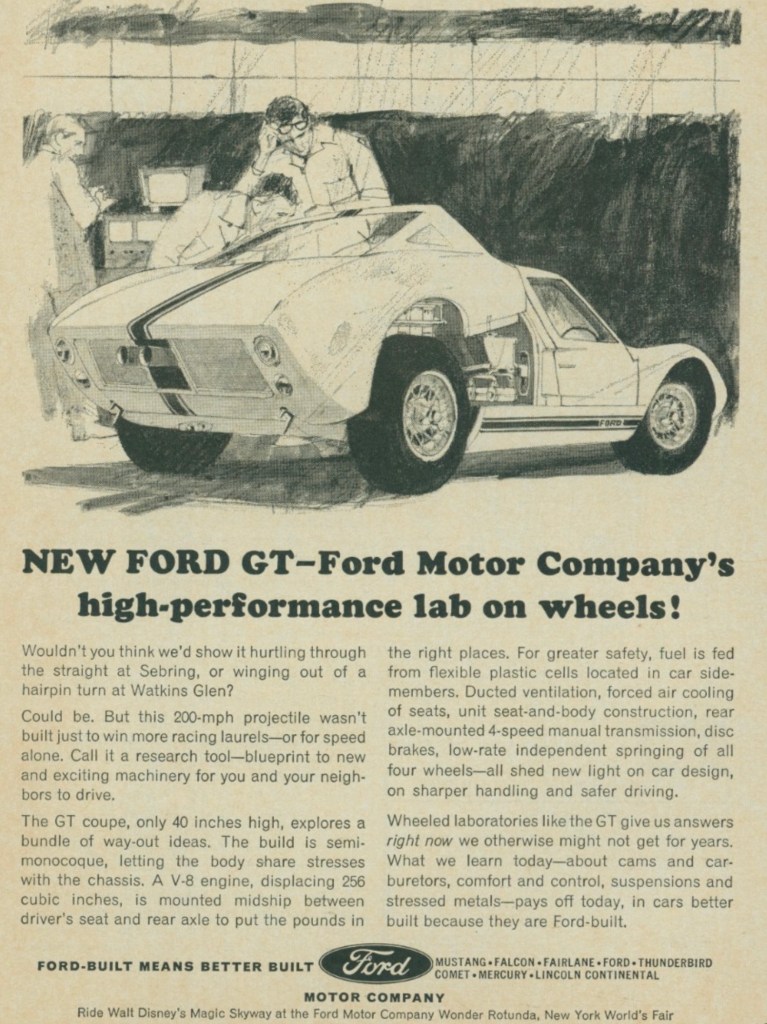

‘Total Performance’, ‘Going Ford is The Going Thing’, and the rest.

I lapped it all up! What was not to love about a global transnational with such commitment to motor racing in every sphere? From Formula Ford to Formula 1, Bathurst to Brands Hatch and the high banking of Daytona to the Welsh forests…God bless ‘em I say.

Credits…

Ford Motor Company, corporateford.com, MotorSport Images

Tailpiece…

If Enzo started it all by ending negotiations with Ford, Eric Broadley finished it, unintentionally.

His Lola Mk6 Ford GT was so late for Le Mans that Eric sent drivers Richard Attwood and David Hobbs ahead and he drove the car to La Sarthe. What a road car…

The two Brits raced it as it arrived at the track; there were no alternative springs, bars or ratios. A missed shift by Hobbs of the tricky Colotti box ended their race too.

Eric Broadley bet-the-farm on that brilliant car but it paid off rather well!

Finito…