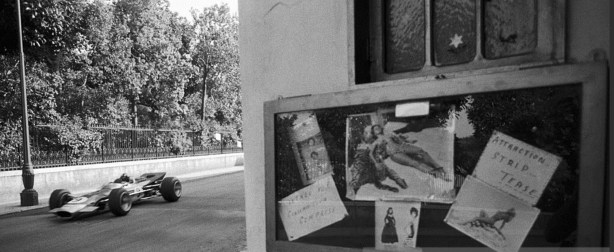

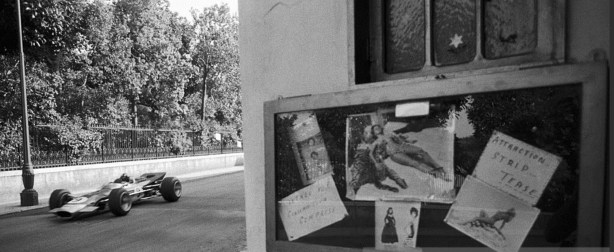

Jack Brabham ponders wing settings on his Brabham BT26 Repco during the Canadian Grand Prix weekend at Mont Tremblant, 22 September 1968…

I blew my tiny mind when Nigel Tait sent me the photo, neither of us had any idea where it was. A bit of judicious googling identified the location as Mont Tremblant, Quebec, a summer and winter playground for Canadians 130km northwest of Montreal.

Regular readers will recall Nigel as the ex-Repco Brabham Engines Pty. Ltd. engineer who co-wrote the recent Matich SR4 Repco article (a car he owns) and has been helping with the series of articles on Repco’s racing history I started with Rodway Wolfe, another RBE ‘teamster’ a couple of years ago.

When Nigel left Repco in the ACL Ltd management buyout of which he was a part, he placed much of the RBE archive with his alma mater, RMIT University, Melbourne. Its in safe hands and available to those interested in research on this amazing part of Australian motor racing history. The archive includes Repco’s library of photographs. Like every big corporate Repco had a PR team to maximise exposure from their activities including their investment in F1. The Mont Tremblant shot is from that archive and unpublished it seems.

Its one of those ‘the more you look, the more you see’ shots; from the distant Laurentian Mountains to the pitlane activity and engineering of the back of the car which is in great sharpness. It’s the back of the BT26 where I want to focus.

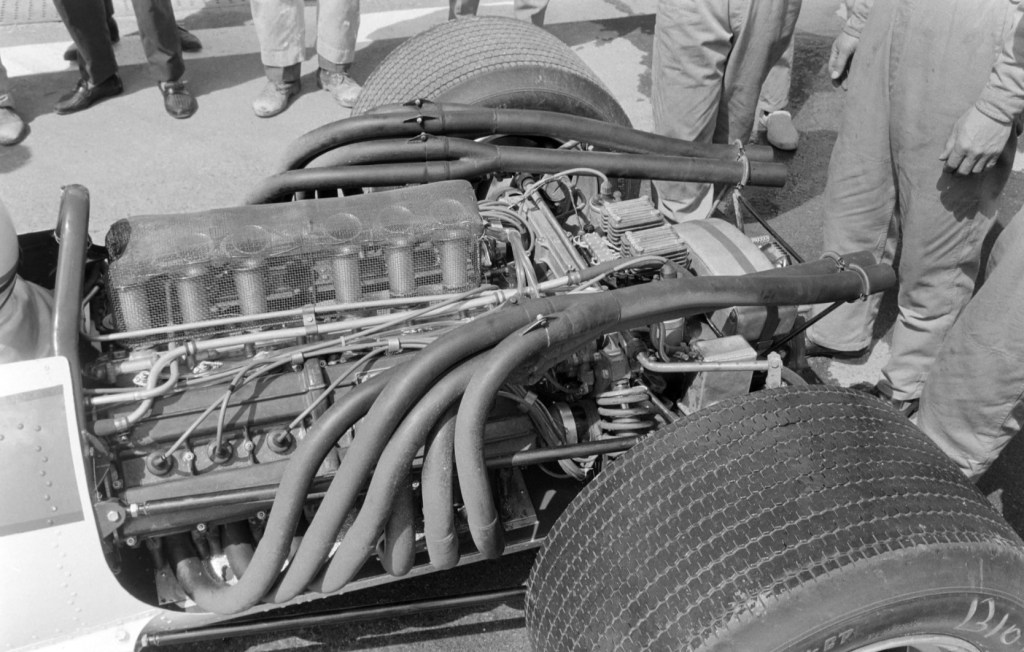

The last RBE Engines article we did (Rodway, Nigel and I) was about the ’67 championship winning SOHC, 2 valve 330bhp 740 Series V8, this BT26 is powered by the 1968 DOHC, 4 valve 390bhp 860 Series V8. It was a very powerful engine, Jochen plonked it on the front row three times, on pole twice, as he did here in Canada in 1968. But it was also an ‘ornery, unreliable, under-developed beast. Ultimately successful in 4.2 litre Indy and 5 litre Sportscar spec, we will leave the 860 engine till later for an article dedicated to the subject.

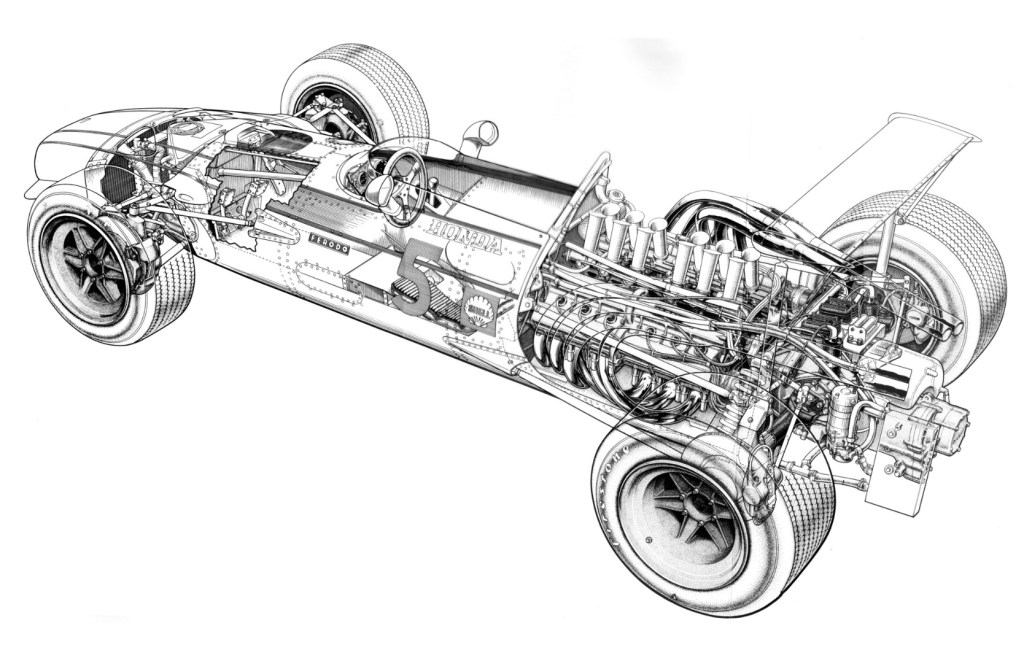

Check out the DG300 Hewland 5 speed transaxle and part of the complex oil system beside it to feed the 860. Also the big, beefy driveshafts and equally butch rubber donuts to deal with suspension travel. It’s interesting as Tauranac used cv’s in earlier designs, perhaps he was troubled finding something man enough to take the more powerful Repco’s grunt, the setup chosen here is sub-optimal in an engineering sense.

The rear suspension is period typical; single top link, inverted lower wishbone, radius rods leading forward top and bottom and coil spring/damper units. It appears the shocks are Koni’s, Brabham were Armstrong users for years.

The uprights are magnesium which is where things get interesting. The cars wings that is, and the means by which they attach to the car…

See the beautifully fabricated ‘hat’ which sits on top of and is bolted to the uprights and the way in which the vertical load of the wing applies it’s force directly onto the suspension of the car. This primary strut support locates the wing at its leading edge, at the rear you can see the adjustable links which control the ‘angle on the dangle’ or the wings incidence of attack to the airflow.

I’ve Lotus’ flimsy wing supports in mind as I write this…

Tauranac’s secondary wing support elements comprises steel tube fabrications which pick up on the suspension inner top link mount and on the roll bar support which runs back into the chassis diaphragm atop the gearbox.

The shot above shows the location of the front wing and it’s mounts, this time the vertical force is applied to the chassis at the leading front wishbone mount, and the secondary support to the wishbones trailing mount. This photo is in the Watkins Glen paddock on the 6 October weekend, the same wing package as in use in Canada a fortnight before. The mechanic looking after Jack is Ron Dennis, his formative years spent learning his craft first with Cooper and then BRO. Rondel Racing followed and fame and fortune with McLaren via Project 4 Racing…

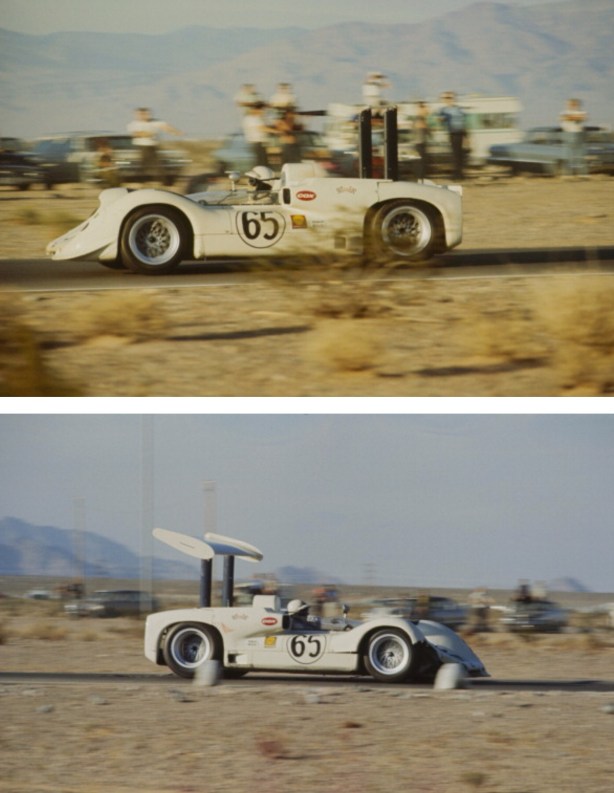

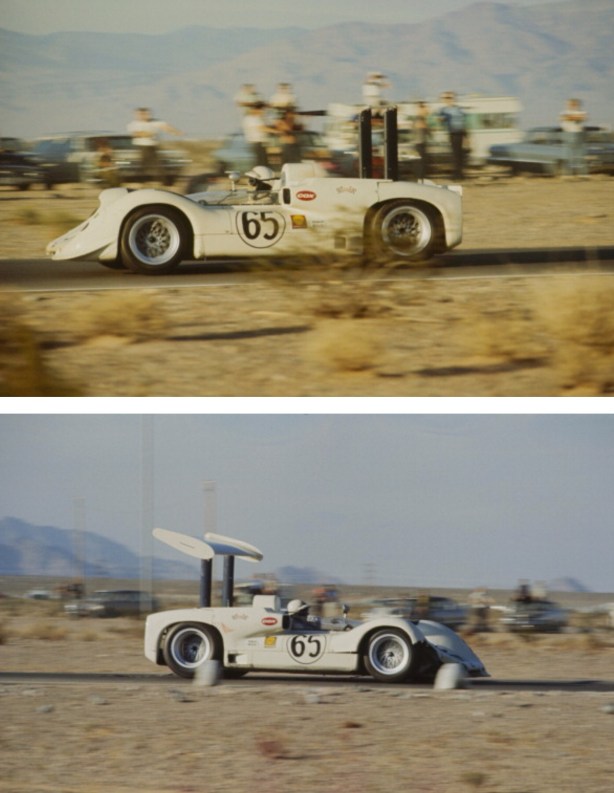

Jim Hall and Chaparral 2G Chev wing at Road America, Wisconsin 1968 (Upitis)

The great, innovative Jim Hall and his band of merry men from Midlands, Texas popularised the use of wings with their sensational Chaparral’s of the mid sixties. Traction and stability in these big Group 7 Sportscars was an issue not confronted in F1 until the 3 litre era when designers and drivers encountered a surfeit of power over grip they had not experienced since the 2.5 litre days of 1954-60.

During 1967 and 1968 F1 spoilers/wings progressively grew in size and height, the race by race or quarter of a season at a time analysis of same an interesting one for another time.

Hill’s winged Lotus 49B, Monaco 1968 (Schlegelmilch)

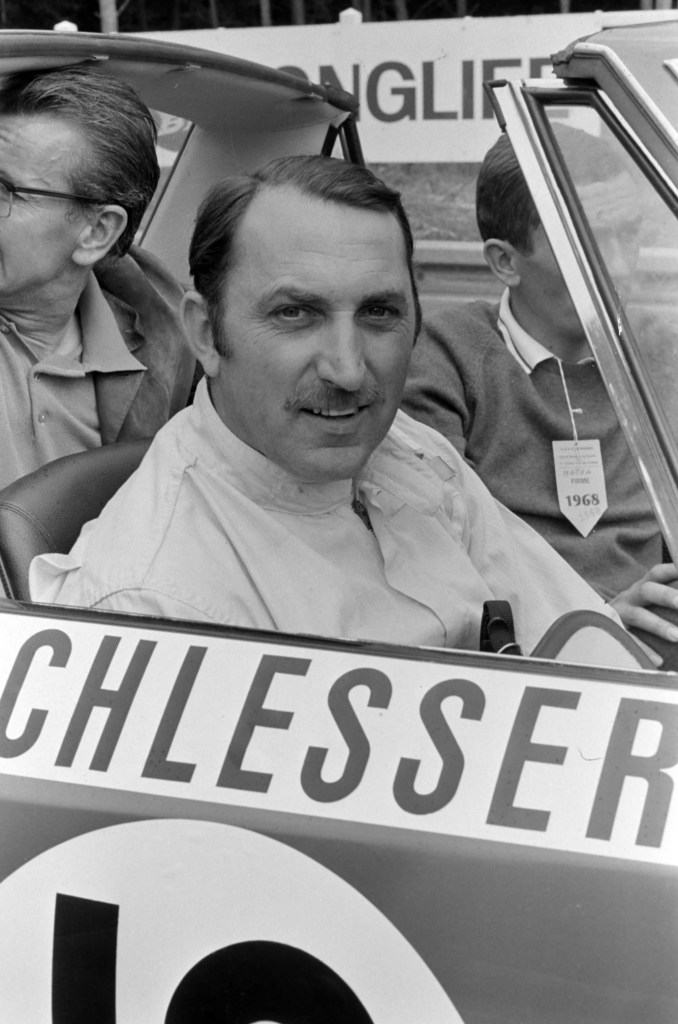

In some ways ‘who gives a rats’ about the first ‘winged Grand Prix win’ as Jim Hall pioneered ‘winning wings’ in 1966, the technology advance is a Group 7 not F1 credit; but Jacky Ickx’ Ferrari 312 win in the horrific, wet, 1968 French Grand Prix (in which Jo Schlesser died a fiery death in the air-cooled Honda RA302) is generally credited as the first, the Fazz fitted with a wing aft of the driver.

But you could equally mount the case, I certainly do, that the first winged GeePee win was Graham Hill’s Lotus 49B Ford victory at Monaco that May.

Chapman fitted the Lotus with front ‘canard’ wings and the rear of the car with a big, rising front to rear, engine cover-cum-spoiler. Forghieri’s Ferrari had a rear wing but no front. The Lotus, front wings and a big spoiler. Which car first won with a wing?; the Lotus at Monaco on 26 May not the Ferrari at Rouen on July 7. All correspondence will be entered into as to your alternative views!

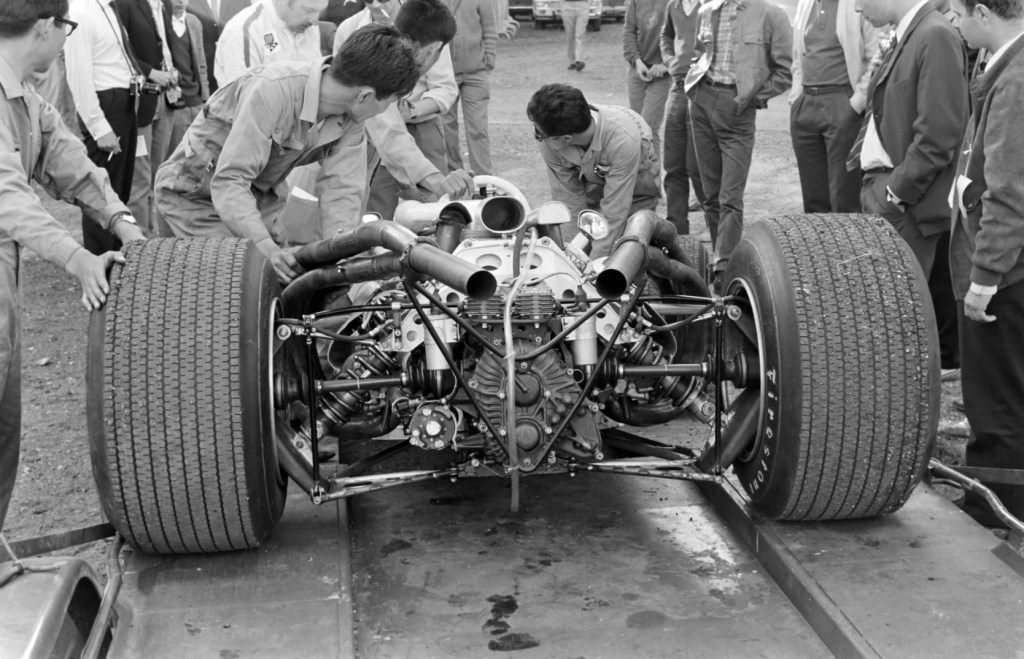

Jacky Ickx’ winning Ferrari 312 being prepared in the Rouen paddock. The neat, spidery but strong wing supports clear in shot. Exhaust in the foreground is Chris Amon’s Fazz (Schlegelmilch)

Lotus ‘ruined the hi-winged party’ with its Lotus 49B Ford wing failures, a lap apart, of Graham Hill and then Jochen Rindt at Montjuic in the 1969 Spanish GP. Both drivers were lucky to walk away from cars which were totally fucked in accidents which could have killed the drivers, let alone a swag of innocent locals.

A fortnight later the CSI acted, banning high wings during the Monaco GP weekend but allowing aero aids on an ongoing basis albeit with stricter dimensional and locational limits.

Mario Andretti has just put his Lotus 49B on pole at Watkins Glen in October 1968, Colin Chapman is perhaps checking his watch to see why regular drivers Hill and Jackie Oliver are being bested by guest driver Andretti who was entered at Monza and Watkins Glen at seasons end! Andretti put down a couple of markers with Chapman then; speed and testing ability which Chapman would return to nearly a decade later. More to the point are the wing mounts; direct onto the rear upright like the Brabham but not braced forward or aft. Colin was putting more weight progressively on the back of the 49 to try and aid traction, note the oil reservoir sitting up high above the ‘box. Stewart won in a Matra MS10, Hill was 2nd with both Andretti and Oliver DNF (Upitis)

Chapman was the ultimate structural engineer but also notoriously ‘optimistic’ in his specification of some aspects of his Lotus componentry over the years, the list of shunt victims of this philosophy rather a long one.

Lotus wing mounts are a case in point.

Jack Oliver’s ginormous 125mph French GP, 49B accident at Rouen in 1968 was a probable wing mount failure, Ollie’s car smote various bits of the French countryside inclusive of a Chateau gate.

Moises Solana guested for Lotus in his home, Mexican GP on 3 November, Hill won the race whilst Solana’s 49B wing collapsed.

Graham Hill’s 49B wing mounts failed during the 2 February 1969 Australian Grand Prix at Lakeside, Queensland. Then of course came the Spanish GP ‘Lotus double-whammy’ 3 months after the Lakeside incident on 4 May 1969.

Faaaarck that was lucky one suspects the Lotus mechanics are thinkin’!? The rear suspension and gearbox are 200 metres or so back up the road to the right not far from the chateau gate Ollie hit. It was the first of several ‘big ones’ in his career (Schlegelmilch)

For the ‘smartest tool in the shed’ Chapman was slow to realise ’twas a good idea to finish races, let alone ensure the survival of his pilots and the punters.

I’m not saying Lotus were the only marque to have aero appendages fall off as designers and engineers grappled with the new forces unleashed, but they seemed to suffer more than most. Ron Tauranac’s robustly engineered Brabhams were race winning conveyances generally devoid of bits and pieces flying off them given maintenance passably close to that recommended by ‘Motor Racing Developments’, manufacturers of Ron and Jack’s cars.

The Brabham mounts shown earlier are rather nice examples of wings designed to stay attached to the car rather than have Jack aviating before he was ready to jump into his Piper Cherokee at a race meetings end…

‘Wings Clipped’: Click on this article for more detail on the events leading up to the CSI banning hi-wings at the ’69 Monaco GP…https://primotipo.com/2015/07/12/wings-clipped-lotus-49-monaco-grand-prix-1969/

Credits…

Nigel Tait, Repco Ltd Archive, Rainer Schlegelmilch, Cahier Archive, Alvis Upitis

Etcetera…

Hill P, ‘Stardust GP’ Las Vegas, Chaparral 2E Chev 1966

Now you see it, now you don’t; being a pioneer and innovator was the essence of the Chaparral brand, but not without its challenges! Phil Hill with 2E wing worries at Las Vegas in 1966, he still finished 7th. Jim Hall was on pole but also had wing problems, John Surtees’ wingless Lola T70 Mk2 Chev won the race and the first CanAm Championship (The Enthusiast Network)

The 13 November 1966 ‘Stardust GP’ at Las Vegas was won by John Surtees Lola T70 Mk2 Chev, CanAm champion in 1966. Proving the nascent aerodynamic advances were not problem free both Jim Hall, who started from pole and Phil Hill pictured here had wing trouble during the race.

The Chaparral 2E was a development of the ’65 2C Can Am car (the 2D Coupe was the ’66 World Sportscar Championship contender) with mid-mounted radiators and huge rear wing which operated directly onto the rear suspension uprights. A pedal in the cockpit allowed drivers Hall and Hill to actuate the wing before corners and ‘feather it’ on the straights getting the benefits in the bendy bits without too much drag on the straight bits. A General Motors ‘auto’ transaxle which used a torque converter rather than a manual ‘box meant the drivers footbox wasn’t too crowded and added to the innovative cocktail the 2E represented in 1966.

Its fair to say the advantages of wings were far from clear at the outset even in Group 7/CanAm; McLaren won the 1967 and 1968 series with wingless M6A Chev and M8A Chev respectively, winning the ’69 CanAm with the hi-winged M8B Chev in 1969. Chaparral famously embody everything which was great about the CanAm but never won the series despite building some stunning, radical, epochal cars.

Phil Hill relaxed in his 2E at Laguna Seca on 16 October 1966, Chaps wing in the foreground, Laguna’s swoops in the background. Phil won from Jim Hall in the other 2E (TEN)

Hill G, Monaco GP, Lotus 49B Ford 1968

Interesting shot of Hill shows just how pronounced the rear bodywork of the Lotus 49B was. You can just see the front wing, Monaco ’68 (unattributed)

Hill taking a great win at Monaco in 1968. Graham’s was a tour de force of leadership, strength of mind and will. Jim Clark died at Hockenheim on 7 April, Monaco was on 26 May, Colin Chapman was devastated by the loss of Clark, a close friend and confidant apart from the Scots extraordinary capabilities as a driver.

Hill won convincingly popping the winged Lotus on pole and leading all but the races first 3 laps harnessing the additional grip and stability afforded by the cars nascent, rudimentary aerodynamic appendages. Graham also won the Spanish Grand Prix on 12 May, these two wins in the face of great adversity set up the plucky Brits 1968 World Championship win. Remember that McLaren and Matra had DFV’s that season too, Lotus did not have the same margin of superiority in ’68 that they had in ’67, lack of ’67 reliability duly noted.

Hills 49B from the front showing the ‘canard’ wings and beautifully integrated rear engine cover/spoiler (Cahier)

Ickx, Rouen, French GP, Ferrari 312 1968

Mauro Forghieri, Ferrari’s Chief Engineer developed wings which were mounted above the engine amidships of the Ferrari 312. Ickx put them to good use qualifying 3rd and leading the wet race, the Belgian gambled on wets, others plumped for intermediates.

Ickx’ wet weather driving skills, the Firestone tyres, wing and chaos caused by the firefighting efforts to try to save Schlesser did the rest. It was Ickx’ first GP win.

It looks like Rainer Schlegelmilch is taking the shot of Jacky Ickx at Rouen in 1968, note the lack of front wings or trim tabs on the Ferrari 312 (Schlegelmilch)

Tailpiece: The ‘treacle beak’ noting the weight of Tauranac’s BT26 Repco is none other than ‘Chopper’ Tyrrell. Also tending the car at the Watkins Glen weighbridge is Ron Dennis, I wonder if Ken’s Matra MS10 Ford was lighter than the BT26? If that 860 engine had been reliable Jochen Rindt would have given Jackie Stewart and Graham Hill a serious run for their money in 1968, sadly the beautiful donk was not the paragon of reliability it’s 620 and 740 Series 1966/7 engines generally were…

Finito…