Brian Hart raced a Lotus F2 and F3 cars for Ron Harris in 1964-66 and was looking for opportunities in the 1.6-litre F2 that had been announced for commencement in 1967. He was after an Unfair Advantage as an innovative engineer.

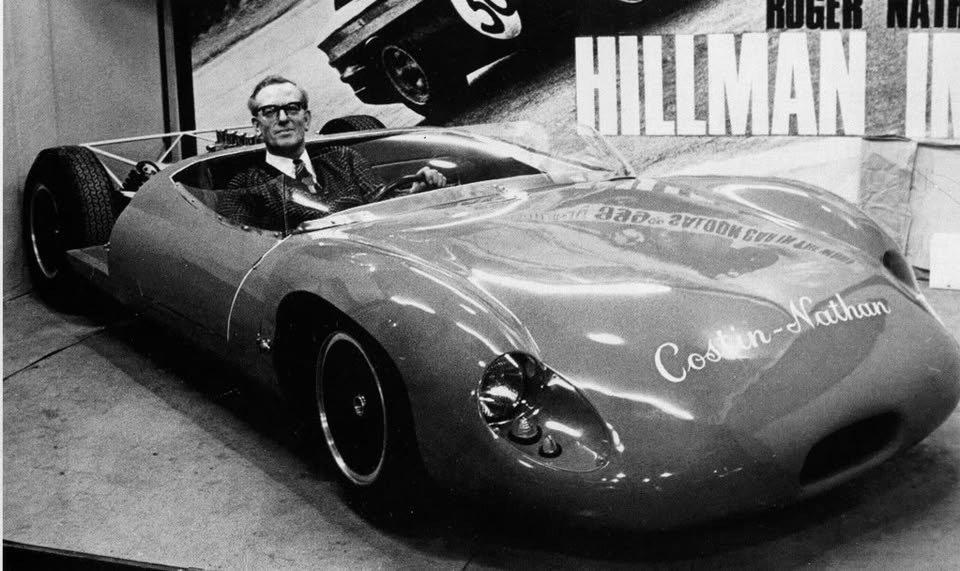

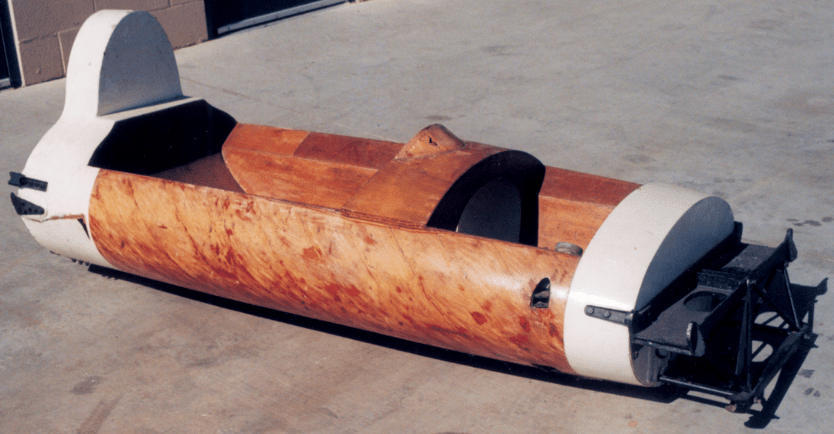

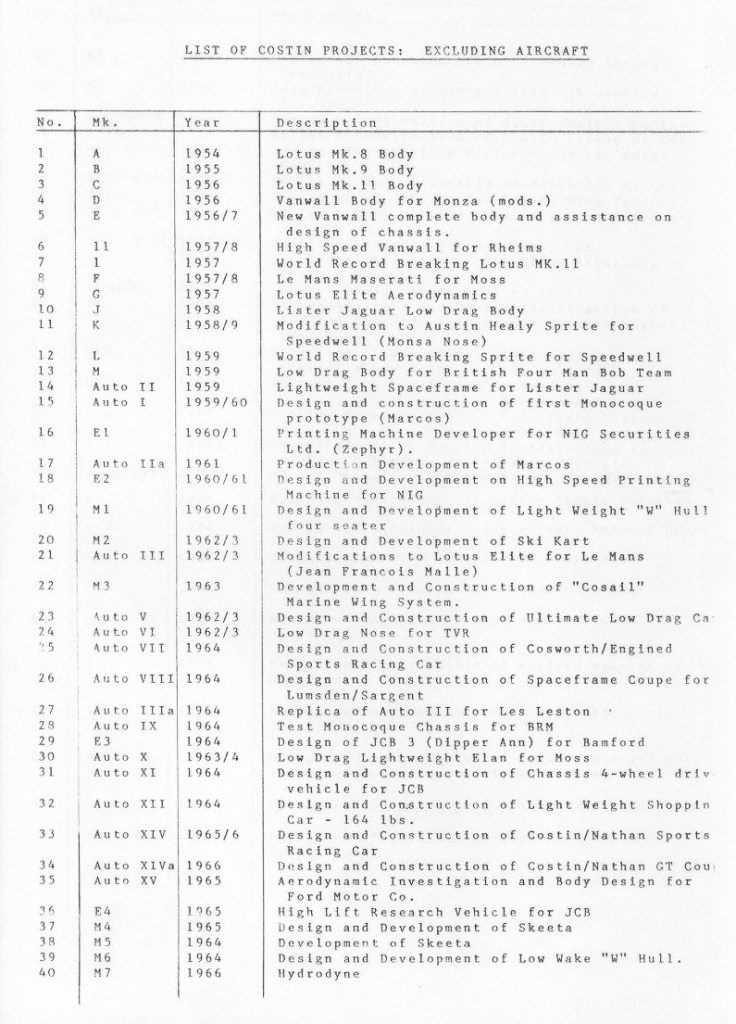

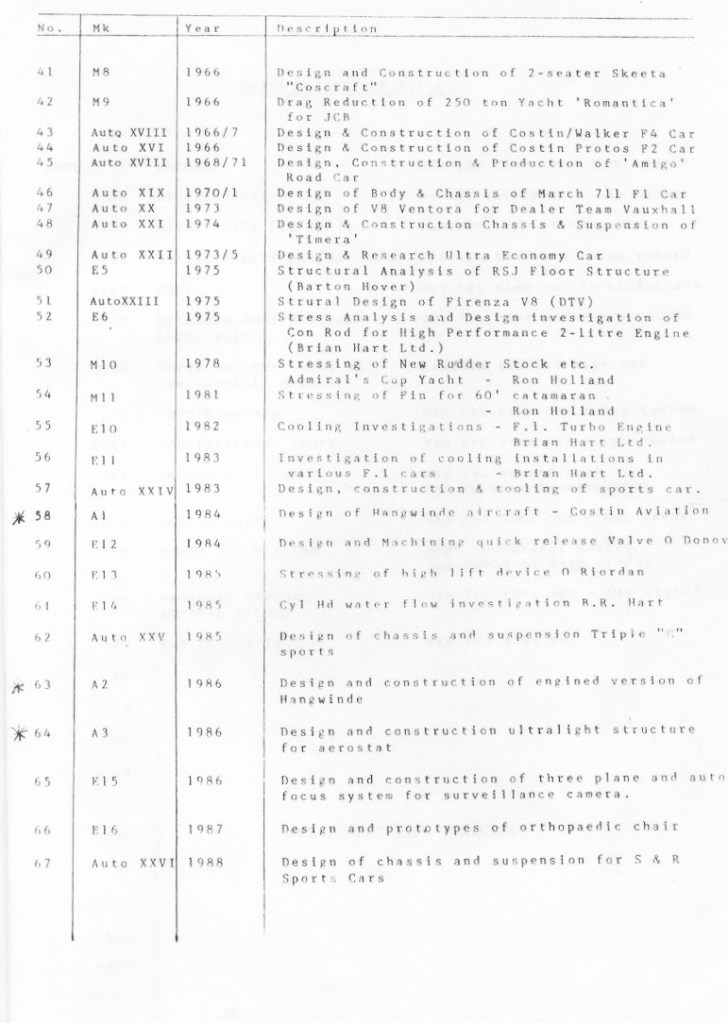

At the January 1966 London Racing Car Show, Hart sought out aerodynamicist/engineer Frank Costin – both were De Havilland Aircraft graduates – about the coming season. Costin was there to sell his new, very light Hillman Imp-powered wooden chassis Costin-Nathan sports car (below). Hart knew of Frank via his younger brother, Mike, who co-founded Cosworth Engineering together with Keith Duckworth, where Brian was an employee.

Earlier, Frank Costin had started Marcos with Jem Marsh. The first Marcos had a wooden chassis too, but Costin’s reputation came from 20 years in aviation, where he developed vast knowledge of the use of wooden structures and aerodynamic theory and practice, to wit, the De Havilland Mosquito

Post war Frank had been summoned by Mike to assist Colin Chapman on the Lotus Mk 8 sports car. Costin improved the car and worked on several more of Chapman’s designs, including Vanwall VW5, the 1958 F1 Manufacturers Championship (then called the International Cup) winning car.

Frank’s Grand Prix involvement extended to the body design of the March 711 Ford Ronnie Peterson drove to second place in the 1971 F1 Drivers World Championship.

Protos Design and Construction…

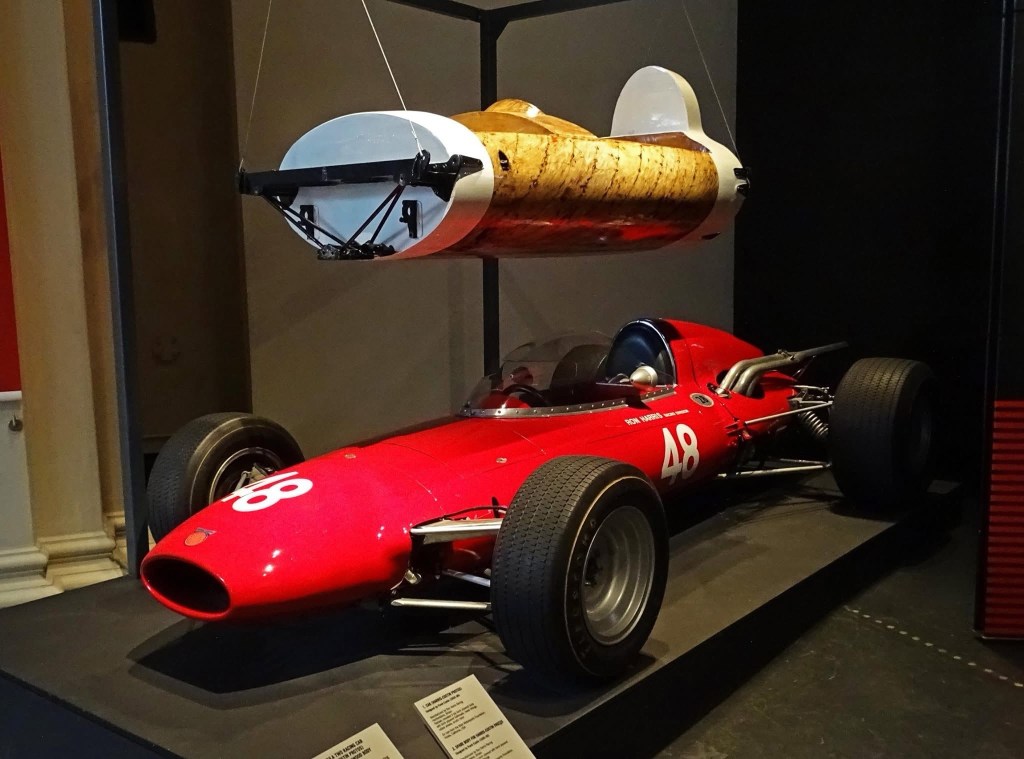

Ron Harris (24/12/1905-18/9/1975), hailed from Maidenhead, Surrey, and was a motorcycle racer/dealer who made his name on Manx Nortons and other machines from the early 1930s until the war. Post conflict, he was involved in film distribution, the cash flow from that business initially funded his return to motorsport, the Ron Harris Racing Division, which ran a pair of Lotus 20 Ford FJs in 1961 (John Turner/Mike Ledbrook).

Success with them attracted Lola’s Eric Broadley’s attention in 1962 (John Fenning/John Rhodes in Lola Mk5s) and the Team Lotus F2 machines from 1963 – Lotus 35/44 – where the driving roster included Peter Revson, Brian Hart, Peter Arundell, Francisco Godia, Piers Courage, Picko Troberg, Eric Offenstadt, Jackie Stewart, Jim Clark etc.

Harris’ Lotus gig came to an end in 1966; it was time to become a manufacturer in 1967!

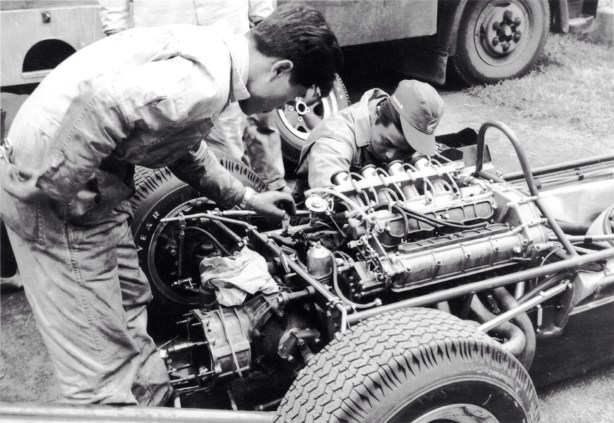

Set in his ways, Costin built the prototype at his home in North Wales with Brian Hart doing the legwork, over 40,000 miles of fetch and carry of component purchase and sub-contracting between London and Wales in the early months of 1967. ‘Frank was a fascinating chap and spoke with such enthusiasm: he was adamant that he could build an F2 car way ahead of its time.’ Brian Hart told Paul Fearnley in a MotorSport 2009 interview.

There was huge excitement among drivers and racing car manufacturers for the new 1.6 F2 with monocoque designs, including the Matra MS5/7, McLaren M4A, and Lola T100, as well as spaceframes, with the dominant car of the year in a variety of hands, Ron Tauranac’s new, spaceframe Brabham BT23.

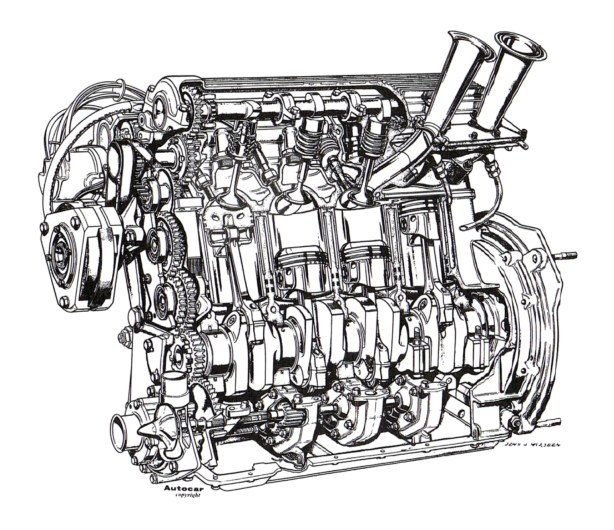

What became the ubiquitous engine/gearbox combination for the duration of 1967-71 1.6-litre F2, was the Ford Cosworth circa 220bhp @ 9000rpm twin-cam, four-valve, Lucas injected four, and the Hewland FT200 five-speed transaxle, was used by most. BMW, Alfa Romeo four-valve engines, the Ferrari Dino 166 and several others duly noted.

Into that environment of competitive activity, the Costin and Harris team – based in Maidenhead, Hertfordshire – designed and built two strong, light, aerodynamically advanced Protos 16 Ford FVA timber-skinned monocoques in 128 days.

Hart, ‘We were making everything apart from the engine and gearbox; there was no template like there was on a privateer Brabham.’

Ed McDonough wrote of the chassis that, ‘Costin’s original intention was to have one set of plywood panels bonded to elliptical plywood end panels and bulkheads with adhesives and further stress-bearing panels of spruce made to form strong box shapes on both sides of the cockpit area. Then, further layers of overlapping strips would form the outer skin. Much like modern carbon-fibre construction, Costin intended for the whole monocoque unit to be placed into a rubber tube to clamp the adhesive and form the proper shape, with the air being sucked out by vacuum. The outcome, Costin reasoned, would be very high levels of strength and low weight in a smooth shape.’

‘Unfortunately, the old spectre of time rushing by meant this elaborate process wouldn’t be possible. So birch plies were used for the outer skin, and the whole thing was clamped conventionally, and the finished wooden structure was smooth-sanded when the glue was dry.’ While this process added weight, after painting, it was hard to tell the difference between this and a steel or alloy unit.’

With the prototype finished in Wales, the other cars were built in Harris’s Maidenhead workshop. Given its unusual construction, Harris coined it ‘Protos’, first in Greek.

With inherent fire risk, Costin designed neoprene-coated alloy fuel tanks, housed in fragile wooden bearers within the chassis. In the event of a big one, the tanks were designed to break away from the car, an element that was tested all too soon…

A magnesium bulkhead was mounted across the front of the car, and together with a light tubular subframe, located top-rockers which actuated vertically mounted, inboard Armstrong shockers, wide-based lower wishbones and an adjustable roll-bar. Front and rear uprights were magnesium.

At the rear, a complex steel tubular spaceframe structure supported the FVA/FT200 combo with six bolts attaching the mechanicals to the tub with the load spread through the wooden monocoque via clever internally glued metal spreaders.

The rear suspension was a combination of magnesium uprights, twin top links, a wide-based wishbone with a pair of radius rods doing fore and aft locational duties, Armstrong shocks and an adjustable roll-bar. Brakes were Girling and tyres Firestone: 9 x 13 inches at the front and 11 x 13 at the rear, with wheels also magnesium.

The car looked the goods when it was launched with some fanfare at Selfridges London store’s ‘Grand Prix Exhibition’ on March 3, 1967.

1967 European F2 Championship…

Harris’s outfit built four tubs (it’s not clear to me if the four build number includes the prototype made in Wales or not), two of which were built up into complete racers with Brian Hart testing HCP1 – Harris Costin Protos – at Goodwood, putting in some competitive times despite the bodywork snagging Hart’s right-hand gear shifting gears, a ‘bubble’ alleviated the problem. Excessive front understeer was cured with changes to the ‘bars and springs.

The cars were entered in the first round of the European F2 Championship on March 24, but failed to appear. All of the other new cars were present with the heats going to Jochen Rindt and Denny Hulme, in Winkelmann and works Brabham BT23 FVAs, with Rindt – the King of F2 – taking the final from Graham Hill, works Lotus 48 FVA and Alan Rees in the other Winkelmann Brabham.

Rees took the Euro F2 Championship points as an ungraded driver. The FIA cleverly created a two-class system. Graded drivers were those who had achieved/won in F1, Can-Am, WSC etc. Ungraded drivers were up-and-comers who had not. Graded drivers could win the races and prize money but were ineligible for Euro F2 Championship points.

Hart raced the car at Silverstone three days later, on March 27, in the BARC Wills Trophy. From grid 16 alongside the Lola T100 BMW of Jo Siffert, Hart and HCP-1 retired in heat 1 when a fuel pump belt broke, while a misfire cruelled his second heat, a recurrent problem throughout the season. Rindt won again.

Harris entered two cars in the Pau Grand Prix (Rindt, Brabham BT23) on April 4 but the machines weren’t ready, with only Offenstadt contesting the GP de Barcelona at Montjuïc Parc on April 9. After several off-course excursions, he retired with brake and misfiring problems, having done only 12 of the 60 laps completed by Jim Clark’s winning Lotus 48 FVA.

The team missed the Spring Trophy at Oulton Park where many of their competitors raced against Grand Prix cars. Up front the Brabham BT20 Repco V8s of Brabham and Hulme were first and second, with the first F2 home Jackie Oliver’s Lotus 41B FVA.

Just two weeks later, the F2 Circus were off to the Nurburgring for the Eifelrennen and there Offenstadt took Graham Hill off in practice and non-started HCP-1.

HCP-2, was finally finished and tested by Hart. Engine misfires continued to come and go, but the team were optimistic as they headed for the RAC Autocar Trophy at Mallory Park on May 14, a British F2 Championship round. Hart qualified a good fifth, but both cars were withdrawn from the race after Costin found a crack in an upright following another shunt by Offenstadt.

New uprights were cast but the team missed the May 21, Limborg GP at Zolder, where John Surtees’ Lola T100 FVA won.

Hart tested HCP-2 at Brands Hatch, where the misfire appeared to have been cured. He then raced it in the London Trophy British F2 Championship round at Crystal Palace on May 29. Offenstadt was allocated HCP-1.

Both did well in practice and in their heat until the misfire returned: Eric was sixth and Brian seventh. On a track he knew well, Hart ran as high as third in the final before troubles dropped him back to tenth. Offenstadt’s troubles continued; this time, he retired with a broken engine mount, while up front was Jacky Ickx in a Ken Tyrrell Matra MS5 FVA.

The next championship round wasn’t until Hockenheim on July 9, so the team set to with some strengthening modifications while noting that both drivers reported the chassis itself to be immensely stiff.

With the work completed the Ron Harris Racing trucks headed for Dover to contest the non-championship Rhein-Pokalrennen on June 11.

Offenstadt demonstrated the promise he showed in 1965 and Hart was in the leading group when he lost fuel pressure.

‘I thought I could win. The car was capable of 180mph, and I was cruising. I could pick up five to six places a lap,’ before the dreaded misfire returned. Brian eventually finished tenth with Offenstadt in a personally rousing fourth. Post-race calculations indicated a top speed of 163 mph without a tow and 172 with one! The customer car favourite Brabham BT23 Ford FVA indicated its user friendliness in that Chris Lambert won the race in a privateer BT23.

Costin observed of his Hockenheim handiwork in 1975, ‘The Protos was approximately 9mph faster at maximum speed than the slowest opposition, and 3-4mph faster than the quicker opposition. This means, given all cars were using the same engine (Cosworth FVA giving 218-220bhp), the aerodynamic advantage of the Protos was about 15bhp over the faster rivals and 40bhp over its slowest competitors at maximum speed.’

With the high-speed Reims Grand Prix coming up on June 25 the team continued to refine the Protos aero, including the extension of the cockpit canopy back to the roll bar.

Practice was again marred by problems, not least Offenstadt crashing again. ‘Some of these problems stemmed from the fact that one of the sponsors hadn’t paid some bills, so there wasn’t the funding for bigger brakes, a real limitation at Reims’, McDonough wrote.

‘Hart and the Protos amazed everyone with the car’s speed, catching and passing Jim Clark and Jackie Oliver (Lotus 48/41B) after a spin. The French crowds cheered as Hart would drop back under braking and then catch and retake the leaders. Unfortunately, the swirlpot cracked on lap 37, and the overheated engine quit, but the car was clearly the fastest of all the F2 machines on the day.’ Despite not finishing, Brian was classified ninth…

The team elected to miss the non-championship GP de Rouen-les-Essarts (Rindt, Brabham BT23 FVA) on July 9 to contest the Deutschland Trophäe Preis Von Baden on high-speed Hockenheim, on the same day.

Offenstadt was replaced by Pedro Rodriguez from this meeting. Mechanical changes included new front and rear subframes, bigger brakes, and on Rodriguez’s rebuilt HCP-1, a more enclosed rear body section.

Rodriguez turned Q3 into the lead of heat 1, but he spun the Protos in the stadium section when it jumped out of gear and ultimately finished fourth in front of Hart. The Mexican again led heat 2, spun again, and then retired with a bent wishbone while Brian was third. Better was to come in the final, where Hart drove an inspired race, battling with Jackie Ickx and Frank Gardner, and ultimately finished third and bagged fastest lap. Gardner won the round on aggregate in a works BT23 FVA from Hart, with Piers Courage’s McLaren M4A FVA third.

Ron Tauranac watched Protos progress closely and figured Costin’s something-for-nothing aerodynamic lessons were worth pursuing. Brabham was battling for F1 World Championship honours with Team Lotus and their Ford Cosworth-powered Lotus 49s, so Ron developed his own canopy cover and bodywork to the very rear of his Brabham BT24 Repco’s Hewland gearbox to buy critical RPMs at Monza. Brabham had trouble sighting apexes so equipped, and didn’t race the car in that form. The point is that Costin had some of the competition thinking…

The team missed the Tulln-Langenlebarn aerodrome race in Vienna on July 16 for undisclosed reasons but rejoined the fray in Spain, where Hart and Rodriguez contested the GP de Madrid at Jarama on July 23. Hart retired his car due to overheating, and Rodriguez was seventh in the race won by Clark’s Lotus 48 FVA.

Zandvoort hosted an F2 Championship round on July 30 that year; the race in Holland was won by Ickx’s Matra MS5 FVA. Hart was sixth, with Rob Slotemaker a DNF due to gearbox problems after only eight of the 30 laps. The Dutchman stood in for Rodriguez, who was racing a JW Automotive Mirage M1 Ford in the Brands Hatch 6-Hours.

Talented German, Kurt Ahrens, raced HCP-1 in the F2 class of the German Grand Prix at the Nurburgring on August 6 and retired, while Hart finished fourth in class with Jackie Oliver the first of the F2s in this non-championship Euro F2 round. Ahrens was an F3 and F2 Brabham veteran of some years, his opinions of the Protos would have been interesting.

The Harris equipe missed the non-championship Kanonloppet, the Swedish Grand Prix, at Karlskoga on August 11, where Jackie Stewart prevailed in a Tyrrell Matra MS7 FVA. The F1 championship aspirant added his name to a long list of F2 race winners (in all championships) in 1967: Rindt, Clark, Brabham, Surtees, Ickx, Widdows, Gardner and Oliver.

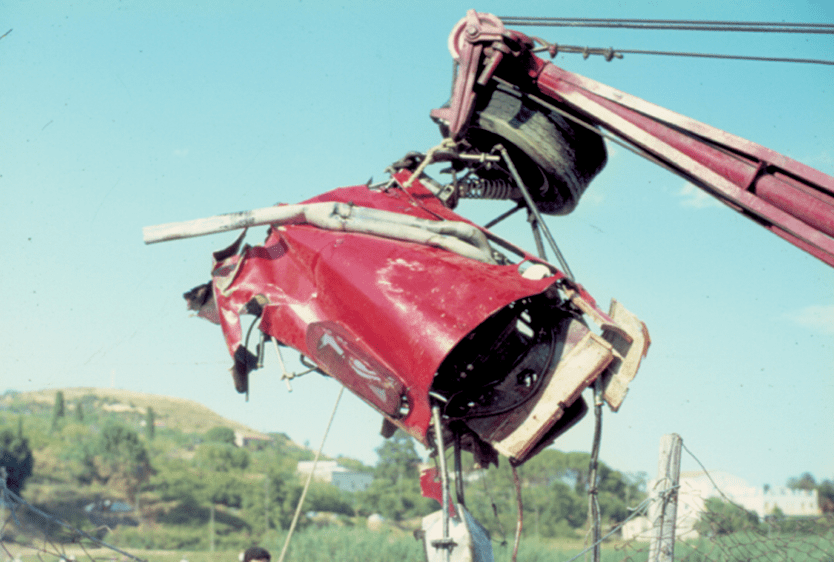

The long haul to the wilds of Sicily for the GP del Mediterraneo at Enna-Pergusa on August 20 followed, a day on which Rodriguez put Costin’s woodie to the ultimate test!

Luc Ghys was there. ‘The track, similar to Hockenheim with long straights, led to fierce slipstream battles. On lap 10, Jackie Stewart’s Matra had Pedro on his tail, and both were passing Beltoise’s leading Matra. The Frenchman gave way to Stewart but immediately tucked in behind, touching Pedro’s car at high speed.’

Beltoise told Ed McDonough decades later how he had been surprised by the speed of the Protos. When Rodriguez attempted to pass the Frenchman’s Matra, Beltoise admitted not being ready for the move and didn’t give Pedro enough room as a consequence.

The car careered out of control, hit the guardrails and broke in half, jettisoning the fuel cells as intended. The tub bore the impact as designed and protected the Mexican from serious nasties: he was still in second place as the Protos-in-bits blasted past the finishing line! Said components were then deposited into Enna’s famous snake-infested lake! Hart had a weekend of consistency, finishing eighth in both heats and the final; both Protos did 165 mph on Enna’s straights.

Pedro, interviewed not long after the race, said philosophically, ‘If it wasn’t for that Protos, I wouldn’t be here talking to you now. It has a wooden monocoque body, you see, and at about 150 miles an hour, it absorbed the impact completely. The car starts to disintegrate, and I went out of the car with the seat on in the middle of the road! The only thing that happened to me was that my right heel was what they call a poolverise fracture.’ Pedro also suffered a small fracture in his left ankle.

‘Ron called us into his hotel room (after the race),’ says Hart, ‘and not only did he say that there wouldn’t be a next year, he also said that he wouldn’t be able to pay off Frank for the remainder of this year.’ Hart’s eighth at Enna was the programme’s denouement. ‘I don’t think we would have won in our second year, but we would have been closer to the front; I think Frank could see that some compromises were needed. But we never got the chance. But what a project. I’ve got a soft spot for that car.’

Despite making four tubs, no more than two complete cars ever existed; HCP-1 was rebuilt over the winter, consuming one of the spare monocoques. Harris and Costin had initially intended to run an evolved Protos in 1968; the same decision was made by most of the major manufacturers to run evolutions of their ’67 cars, but the year had been so expensive that Harris decided to run Tecnos instead.

When the Pederzanis delivered the Tecnos hopelessly late, Rodriguez, clearly fond of the Woodies, asked Harris to enter a Protos for the non-F2 Championship Eifelrennen at the Nurburgring on April 21.

Pedro raced HCP-1 and Vic Elford HCP-2 on his single-seater debut. Rodriguez retired out of fuel while Vic finished a splendid seventh. Man On The Rise Chris Irwin won in a works Lola T100 FVA, his next visit to the Eifel didn’t end quite so well.

Sadly, that was it, Rodriguez raced the first of Harris’ Tecno PA68 FVAs at Crystal Palace on June 3 1968, then added insult to Ron Harris’ injury by crashing it on the first lap of the final, having placed fifth in his heat…the Protos never raced again.

The 1968 season was so expensive and difficult for Harris that it ended his active involvement in racing. Much of his equipment disappeared or was damaged on the late-season Temporada tour in South America, so ultimately everything was sold off.

Hindsight…

Brian Hart told Paul Fearnley, ‘It was incredibly fast in a straight line (a useful asset in those slipstreaming days), but it had shortcomings. The engine was carried in a metal subframe, and where this was affixed to the wooden tub was a weak point. And because the car had a rounded shape, the side fuel tanks were carried quite high, giving a bad CoG. It was heavy, too – about 25kg more than the rest – and when this was coupled with an initial lack of anti-roll bars (Costin had yet to be convinced of their necessity), it was a bit of a handful in the corners. One of our biggest failings was our inability to engineer the car once the season had started: money was tight, and we had no baseline from which to work.’

Eric Offenstadt said of the car to Michael Dawson, ‘I had a picture of my pole position at Hockenheim in front of Jochen Rindt with the Protos…but I lost it. The roadholding was “peculiar”, not because of the wooden chassis, but because of “rare suspension geometry”.

Firestone funded the project, which explains in part why Ron Harris was adventurous. The challenge to design, build, develop, prepare and race a new car was a far more complex and costly process than racing works-Lotuses that were competitive outta the box.

That the designer was reluctant to leave Wales must have made the development of the car a challenge!

Despite the design’s shortcomings, it was clearly competitive on faster tracks, with suspension geometry the area that required focus over the 1967-68 winter, had the Harris team raced on with the Protos.

The Ford Cosworth FVA engine problems the Harris team experienced in 1967 are somewhat ironic given Brian Hart Engines Ltd’s capabilities in preparing and developing these engines by 1969!…

What extraordinary racing cars those Protos were/are.

Historic Era…

Englishman Richard Whittlesea bought the two cars, HCP-1 complete and HCP-2 as a rolling chassis, restoring and racing HCP-1 and displaying it at Donington, before selling the cars to American Norbert McNamara, then later he sold them to Californian Brian Blain/Blain Motorsports Foundation, who retains them.

Etcetera…

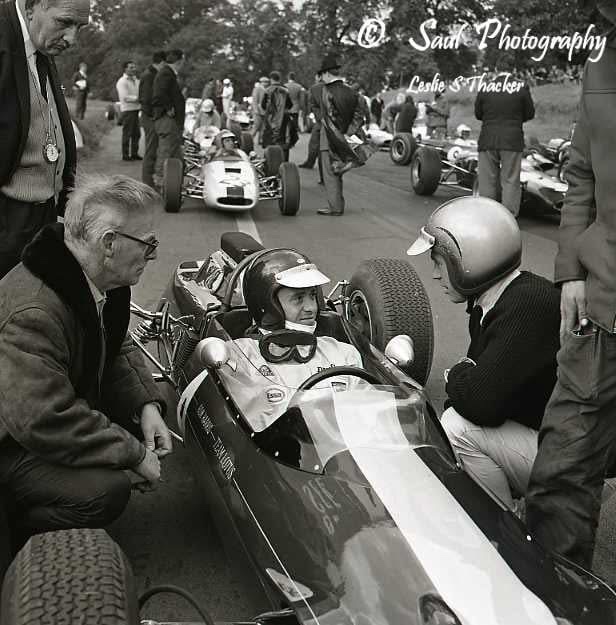

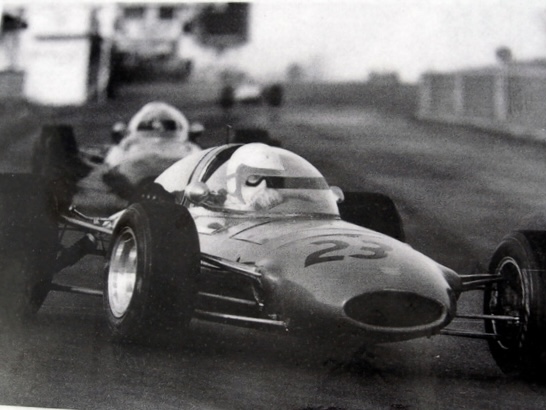

The Protos Ford FVA of Eric Offenstadt on the Montuic Park grid, April 9, 1967. Nice shot of the swept-back rockers and cast-mag upright

Credits…

Getty Images, Hans Fohr Collection, Steve Wilkinson Archive, Ed McDonough article on supercars.net, Pete Austin, Les Thacker, Josef Arch, ‘Aerodynamics of the modern car’, Frank Costin in Automotive Engineer magazine in 1975, ‘Ply in The Ointment’ Paul Fearnley, MotorSport November 2003, Formula 2 Racing and Frank Costin Autos Facebook pages, Mike Stegmann, Rafael Calatayud Collection, Blain Motorsport Foundation, Jim Gleave

Tailpiece…

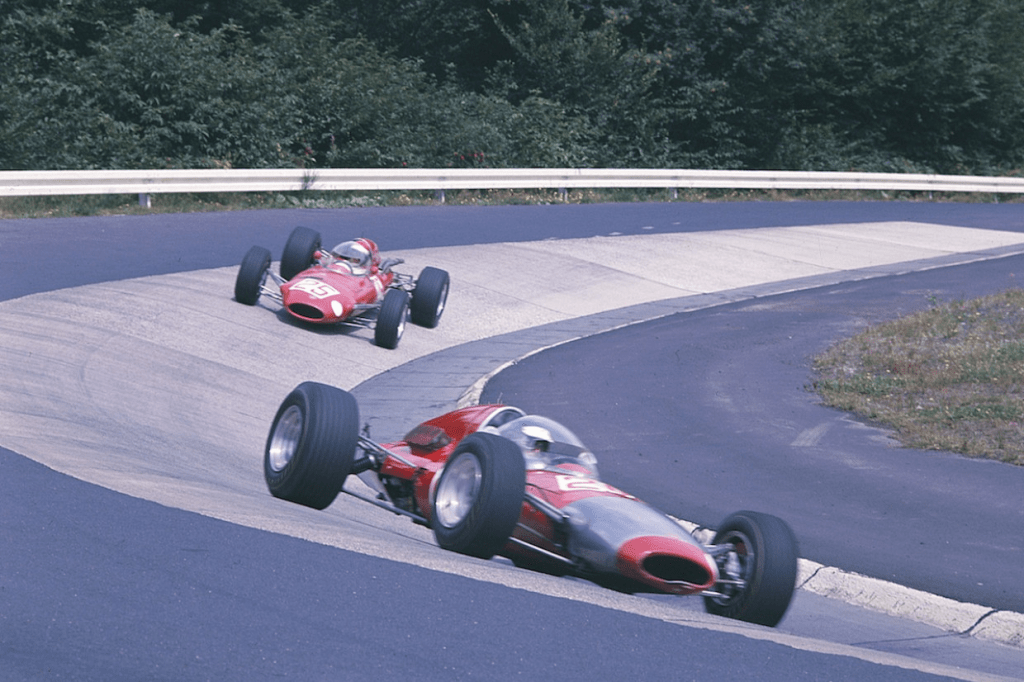

Hmmm…which cars are the Protos’ I wonder?

Reims June 25, 1967. DNF’s for both Hart and Offenstadt. Jochen Rindt’s Winkelmann BT23 FVA won from Graham Hill, John Surtees, Jackie Stewart and Denny Hulme, World Champions all! In its heyday(s) F2 was absolutely marvellous.

Finito…