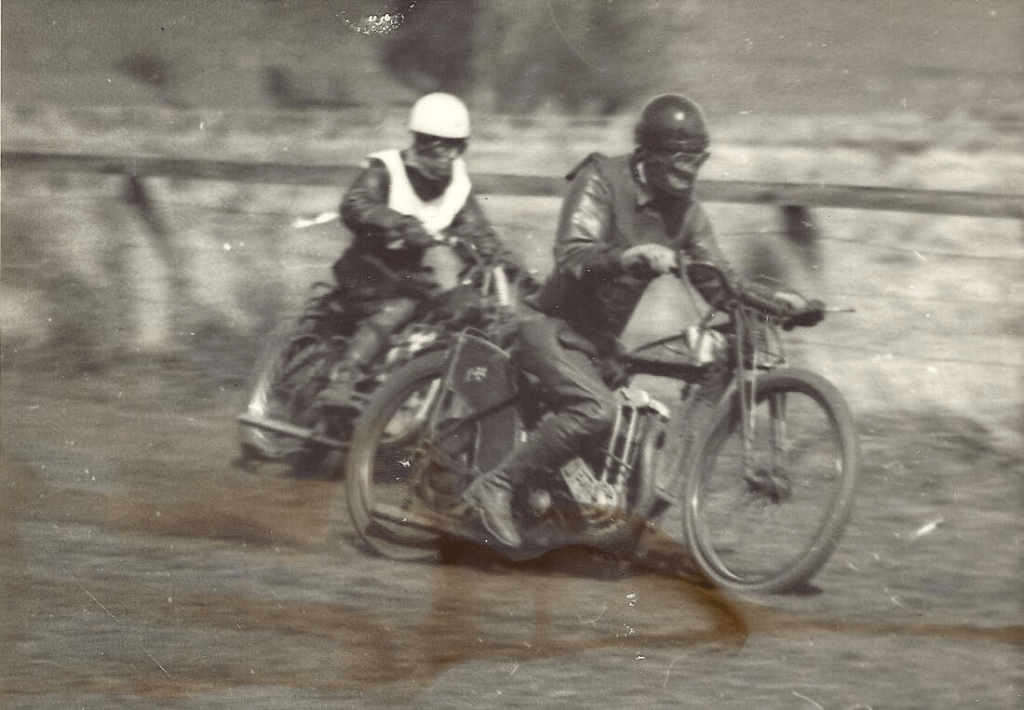

This is the first in an ongoing series of pieces based on my (vulgar) first response to a photograph that makes no sense to me. Regular readers will appreciate that an inferior intellect like mine elicits such responses often.

When I first saw the photos – the first one above and the second last – I thought no way were they in Australia, both had a USA feel to me, wrong on both counts.

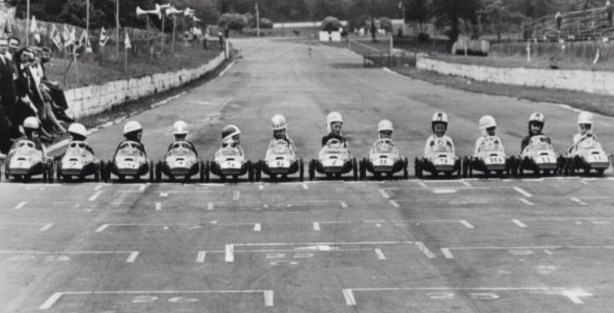

The first is from me’ mate Bob King’s Collection and was taken at the Warragul Showgrounds pre-War. The last was shot at Drouin, just up the road, that both photographs were taken in two small West Gippsland townships close together 100km to Melbourne’s east is coincidental.

King’s caption for the ‘bike race photograph reads “Darby – in front – was killed in this race.” Sadly that is the case. A bit of judicious Troving confirms that the small Warragul community ran grass-track meetings on their local showgrounds from the mid-1920’s until 1941, with a final meeting, perhaps, in 1953. Ploughing through the results of meetings in the 1930s revealed that Leslie Edwin Darby is our man.

The Auto Cycle Union of Victoria sanctioned events were usually run over the Easter long-weekend on a track “6 1/2 furlongs” (1308 metres) long, timed after the speedway and trotting (nags) seasons had ended, these ran from November-April. As the photo shows, the crowds were huge, 6000-8000 people, not bad for community of less than 500 at the time.

Darby was a star of the sport, holding over 30 Australian and Victorian grass track championship wins and over 150 placings. He had won four Victorian and Australian championships at Warragul in the 350 and 500cc classes. He also competed with success in road racing, holding the 250cc lap record at Phillip Island, in 1937 he set FTD at Rob Roy hillclimb, besting all the cars present.

Showing his adaptability, Darby also contested sidecar events, winning the Victorian Sidecar Championship in 1934, and placing third in the famous Victorian Tourist Trophy at Phillip Island held over 75 miles that same year.

Les had a lucky escape at Warragul in April 1936 when he crashed at high speed, somersaulting over a perimeter fence when his ‘bike struck it. Unharmed, other than by cuts and abrasions, he jumped aboard another machine and won the Australian All Powers Three Mile Championship. Warragul claimed three lives, its variety of ever present dangers were demonstrated by Bud Morrison who was thrown from his bike into an adjoining creek and nearly drowned before ambulance officers intervened, during the same 1936 meeting.

Poor Darby’s luck ran out in tragic circumstances on Boxing Day 1940. Shortly after passing the finish line at the end of the the final of the Gippsland Solo Scratch – in which he was battling Edward Smith for the win – Smith, narrowly the victor, lost control of his machine just after the line and fell. Darby swerved in avoidance and hit the fence at over 70mph before cannoning into the crowd. He was declared dead at West Gippsland Hospital shortly afterwards, aged 32. Two spectators were seriously injured but survived.

Les Darby is buried at Kew Cemetery, close to where I grew up, I shall make a pilgrimage to pay my respects soon.

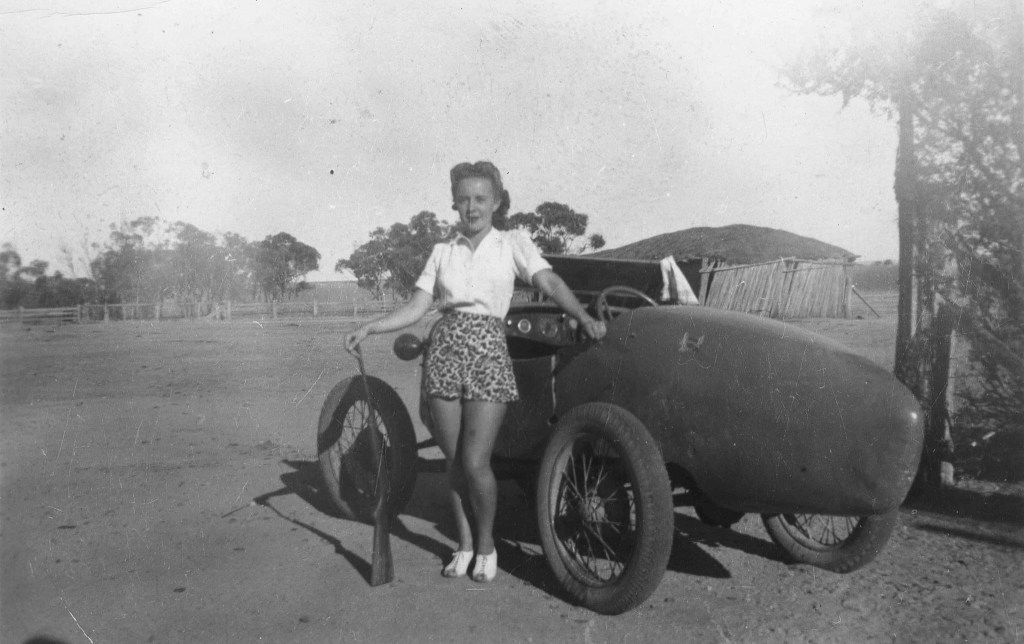

Thankfully the Drouin shot is happier but no less impactful.

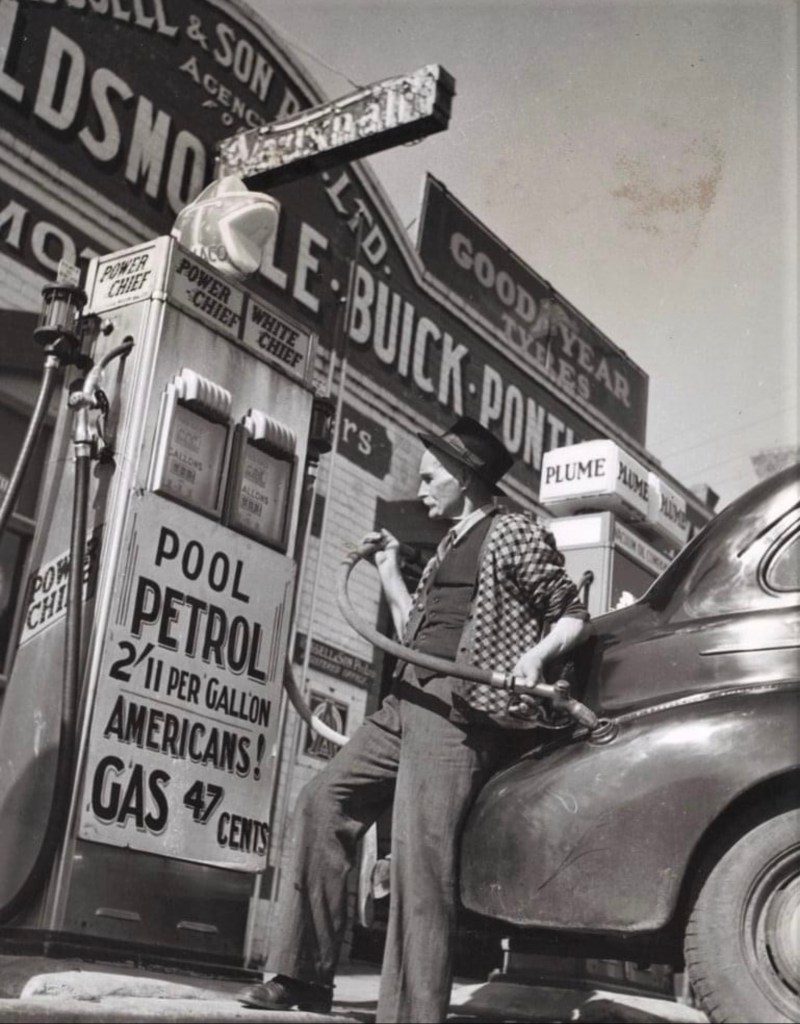

William Russell is putting the four-gallon monthly ration of petrol into a customers car at Drouin in 1944. The sign is for the benefit of United States servicemen using the Princes Highway, a main Melbourne-Sydney artery.

The photo is one of a series of Drouin shots taken by government photographer Jim Fitzgerald (Australian Dept of Information) to document the impact of the war on ordinary people, they were used here and in the US.

William Russel & Son Pty. Ltd. the biggest servo in Drouin had two sites employing 16 people and appears a good business with franchises for Oldsmobile, Buick and Pontiac. Aged 80, William was still on-the-tools…

Born in Brechin, Scotland in 1865, a year later he emigrated to Australia with his parents and older brother, a voyage which took 95 days. William was apprenticed as a blacksmith, wheelwright and coach builder, acquiring the Monroe and Morse, Drouin business in 1890. As horsepower evolved from hooves to wheels the business evolved into a garage, car showroom and servo. William died on May 11 1950 and was such a highly respected member of the local community the hearse taking him on his final journey was followed by over 100 cars.

Credits…

Bob King Collection, Trove – various newspapers, The Gazette-Warragul and Drouin, motorsportmemorial.org, Speedway and Road Race History – SRRH

Tailpiece…

After I posted this article I sent it straight to Bob King who provided the shot, or more specifically I scanned it during one of our many illicit, keep-ya-sanity, Covid 19 trysts at his place in the winter of 2020. We Victorians were locked up tighter than a nun’s chastity belt by our beloved Dictator Dan (State Premier Dan Andrews) for most of that year, and a good chunk of 2021, bless the Chinese Alchemists and their magic potions.

His response was “All good stuff, I now recall the name of the patient who gave me the Darby photo, John Soutar, I believe. I think he raced against Darby, my last contact with him was 30 years ago, I just googled Soutars Garage, which is still in Warragul, may be worth a visit.”

There ya go, that explains the WTF photo above.

King’s caption for it is “John Soutar”. The scan was in Bob’s album above the one of Darby in action. I’m sure he made the connection two years ago when we were scanning away, this time the geriatric at fault is me not him…Still, we got there in the end, albeit I think Mr Soutar was a young fan rather than a competitor.

Finito…