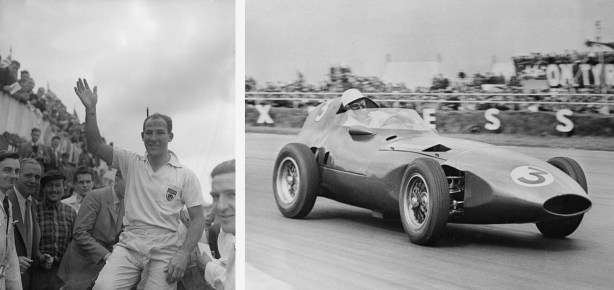

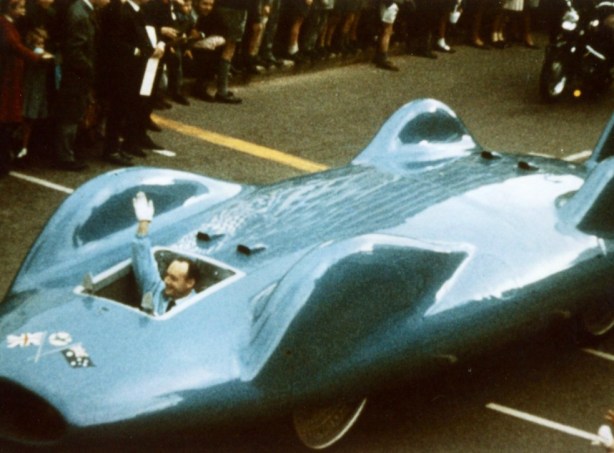

Stirling Moss on his way to Ain Diab victory in his Vanwall VW5, 1958 (Moss Archive)

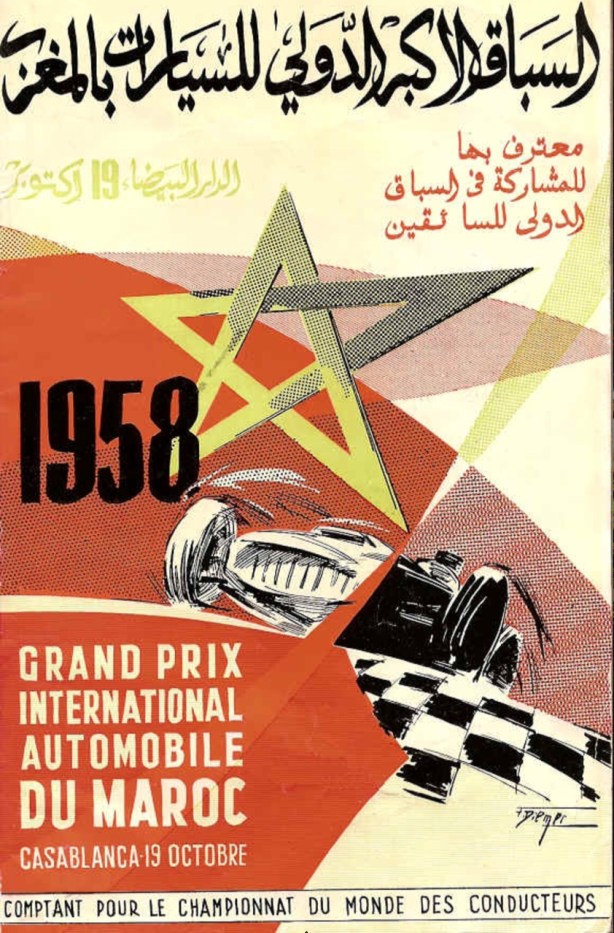

Stirling Moss, Vanwall VW57 and Mike Hawthorn, Ferrari 246 went to Morocco for the final round of the 1958 Championship, with Moss needing to win and set fastest lap and Hawthorn to finish no lower than third to take the title…

Morocco had recently gained its independence from Spain and used the race to help establish its global identity. The newly crowned King Mohammad V attended ‘Ain Diab’, a very fast, dangerous road circuit on public roads near Casablanca.

Moss took the lead, with Phil Hill also starting well- Hill waved teammate Hawthorn through to chase Moss with Brooks challenging in the other Vanwall. Moss set a new lap record, Ferrari slowed Hill to allow Hawthorn into second. Moss ran into Wolfgang Seidels’ Maserati 250F, damaging the Vanwalls nosecone, but fortunately not the radiater core.

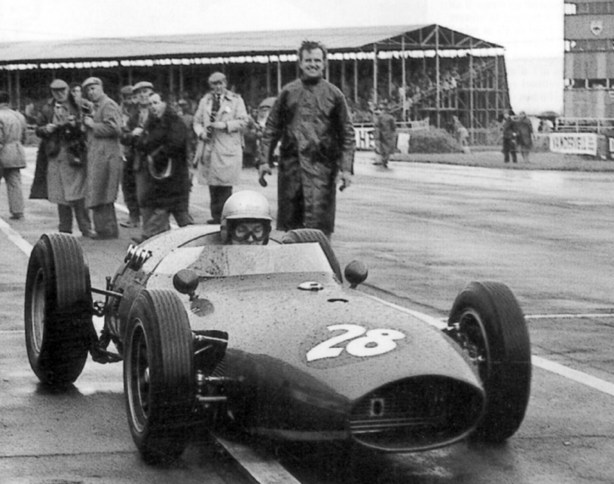

Tragedy struck on lap 42 when the engine in the Stuart Lewis-Evans Vanwall blew, the car’s rear wheels locked then the car careered into a small stand of trees- the vulnerable tail tank ruptured and caught fire, Lewis-Evans jumped out but was disoriented and headed away from fire marshalls who may have been able to minimise the terrible burns from his overalls- despite being flown home to the UK he died in a specialist hospital six days later.

Stuart Lewis-Evans, Morocco 1958. His death robbed Britain of its great ‘coming-man’ (The Cahier Archive)

Stunning Moroccan backdrop, Hawthorn, Ferrari Dino 246 (Unattributed)

Moss’ car survived the heat despite the damaged Vanwall nosecone having hit Seidel’s Maser 250F ‘up the chuff’ taking the win and the Constructors Championship for Vanwall (Unattributed)

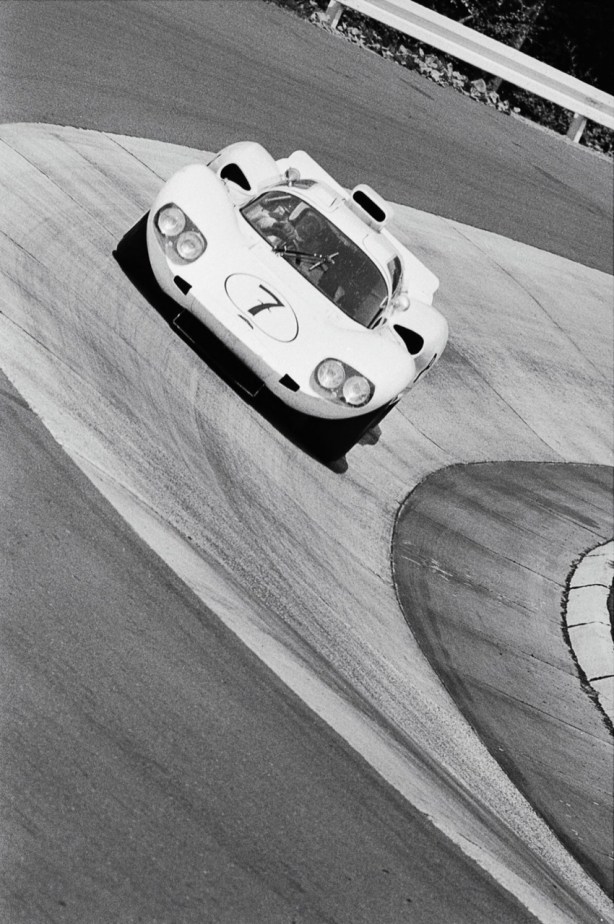

Phil Hill turns his Ferrari Dino 246 into an open right hander on the prodigiously fast Ain Diab road circuit, Casablanca, Morocco 1958- he finished third (Unattributed)

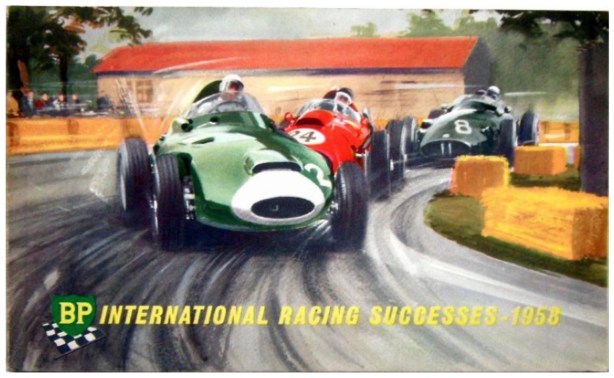

Moss won the race, and Hawthorn the Drivers Championship, but the Constructors Championship was won by Vanwall in a fitting reward for Tony Vandervell who had passionately supported the BRM program before setting out on his own, frustrated by the process of management by committee and the lack of agility which went with it.

Hawthorn shortly thereafter announced his retirement from racing, aged 29, and, ‘dicing’ with Rob Walker’s Mercedes on the Guildford Bypass not far from his home, crashed fatally in his Mark 1 Jag 3.4- an horrific end to a tragic season for British motor racing.

This article started life as a piece I wrote in September 2014 about the Moroccan GP and then over time morphed into a rough bitza on Vanwall of 1,500 words, before substantially re-writing it as a 10,000 word feature in February 2020. The article uses as its primary technical resources two 8W Forix articles- one by Ron Rex ‘The Vanwall Grand Prix Engines’, quite staggering in the level of detail, http://8w.forix.com/vanwall-grandprix-engine-introduction.html and another by Don Capps ‘A Year by Year Look at the Vandervell Racing Machines including Thinwall Specials’ http://8w.forix.com/vanwalls.html

If you are interested in the topic do read these articles and others on Vanwall on that site- you will be fascinated for a weekend at least.

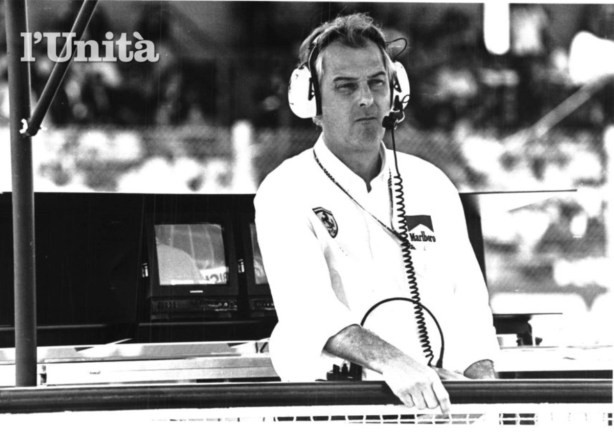

Tony Vandervell…

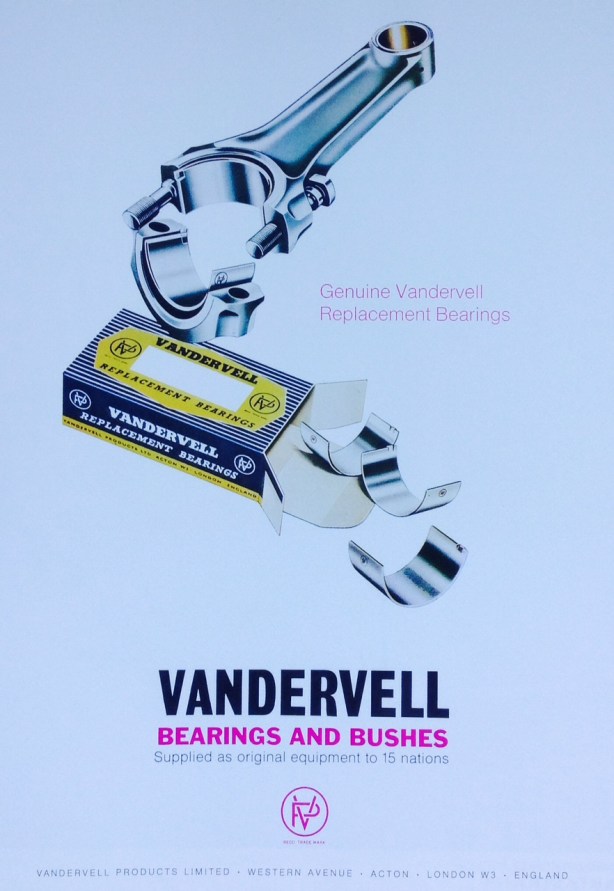

Vandervell Products ad in the ‘BRM Ambassador for Britain’ booklet (Stephen Dalton Collection)

Guy Anthony ‘Tony’ Vandervell (TV) was the son of Charles Vandervell, the fouder of CAV, later Lucas CAV.

He made his fortune from the production of ‘Thin-Wall’ bearings under licence from the innovative American inventor- Cleveland Graphite Bronze Company, these products were made by Vandervell Products Ltd (VP) from 1933 in a purpose built factory at Western Avenue, Acton, west of London.

As a captain of the automotive industry Vandervell was invited to be a member of the British Motor Racing Research Trust (BRM) in 1947 but he soon tired of BRM’s ‘management by committee’ and the consequent lack of agility so started an independent race program with a series of Ferraris modified by VP called ‘Thin Wall Special’.

He was born on 8 September 1898 and died on 10 March 1967.

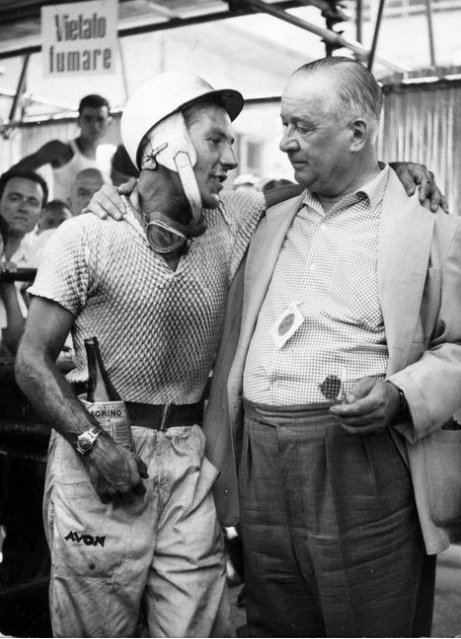

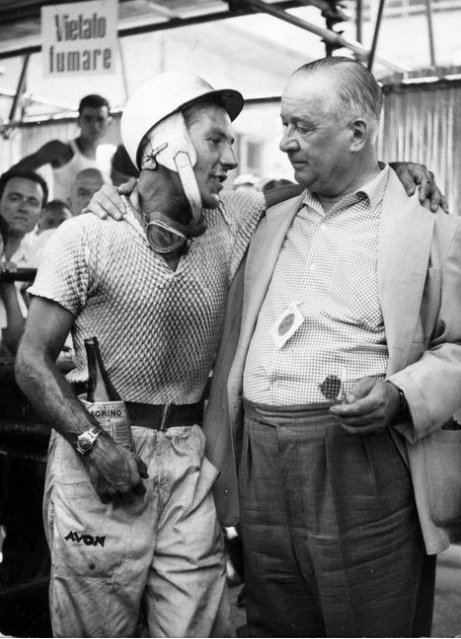

The Chief, Tony Vandervell with Tony Brooks in the Monza pitlane in 1958 the day before Brooks went out and won the Italian GP, Vanwall VW5 (John Ross)

Reg Parnell in Ferrari 375 Thinwall 3 before going out and beating the three Alfa Romeo 159s of Fangio, Farina and Bonetto in the May 1951 International Trophy at Silverstone- the race was held in teeming rain and ended after 6 laps, no official winner apparently but Parnell got the prize which tends to indicate he won! Car #29 is Johnny Claes, Talbot Lago T26C (Getty-GP Library)

Peter Whitehead in Thinwall 3, Ferrari 375 during the 1951 British GP at Silverstone, 9th in the race won by Froilan Gonzalez Ferrari 375- Ferrari’s first championship GP win

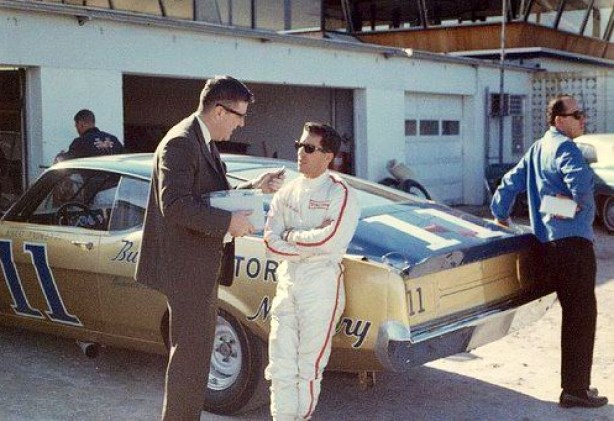

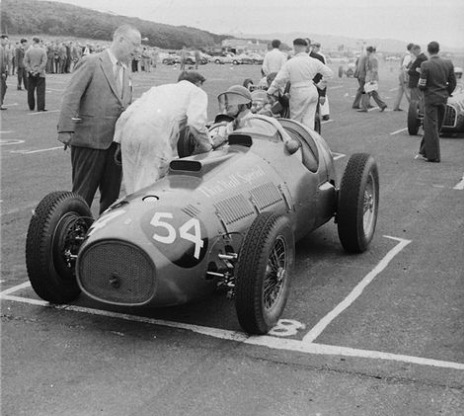

Mike Hawthorn in the Ferrari 375 V12 ‘Thinwall 4 Special’, National Trophy Race, Turnberry Airfield circuit, Scotland 23 August 1952. Tony Vandervell is to the left of the mechanic, Hawthorn is on pole and sportingly allowed the BRM mechanics to repair a leak in a water rail on Reg Parnell’s car, before stepping aboard his car, and then found a box full of neutrals at the start and retired it shortly thereafter. Parnell won the race from Bob Gerard’s ERA and Ken Wharton in the second BRM V16 (Unattributed)

The first Thinwall (i have used ‘Thinwall’ throughout this article but note the correct names of the cars were ‘Thin Wall Special’) was a 1949 Ferrari 125 GPC- a 1.5 litre supercharged V12 short wheelbase machine which was returned to Ferrari after examintion by BRM, chassis number unknown. Describing these cars is context for the Vanwalls which followed, a description of the Thinwalls and the modifications made to them is an article in itself for another time.

By 1950 VP had built an additional factory at Cox Green, Maidenhead complete with engine test beds and it was here that the Ferrari, and later Vanwall engines were built and tested. The Vanwall racing team (VR) itself was based at Acton with Fred Fox in charge and Phil Watson as Chief Mechanic with close access to VP’s drawing office, toolroom and major workshop located in the main factory over the road. In essence, by the end of 1950 all the necessary infrastructure was in place to take on and beat the best in the world.

Thinwall 2 was a 1950 Ferrari 125, it was similarly powered to the first car but had a more powerful twin-plug V12. The long wheelbase chassis was numbered ‘125-C-02’ and had swing axle rear suspension, it was returned to Maranello to be rebuilt into Thinwall 3.

The 1951 Thinwall 3/Ferrari 375 used, as noted above, the same chassis as ‘2’ but fitted with a normally aspirated 4.5 litre, single-plug V12 with a de Dion rear end- retained by the team, it was broken up in 1952.

Thinwall 4/Ferrari 375 was a long-wheelbase ‘Indianapolis’ 375, chassis number ‘010-375’ and was again a 4.5 litre V12 but this time twin-plug and de Dion rear axled- the car was retained by the team.

The Ferraris raced mainly in British Formula Libre events providing the main opposition to the BRM Type 15 V16 which was essentially too late for F1 before the formula changed, rendering it obsolete.

Vandervell was restless and wanted to race in the new 2 litre F2 of 1952-1953 which of course became the category to which the World Championship was run in those years.

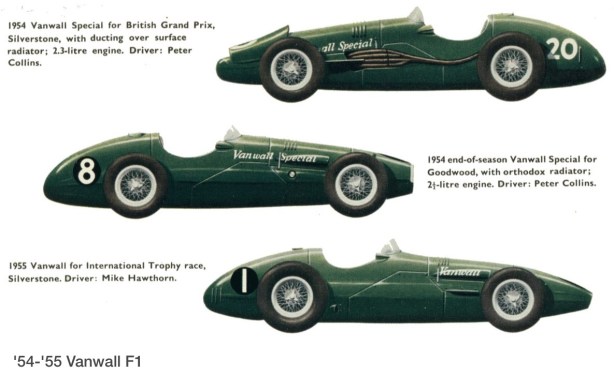

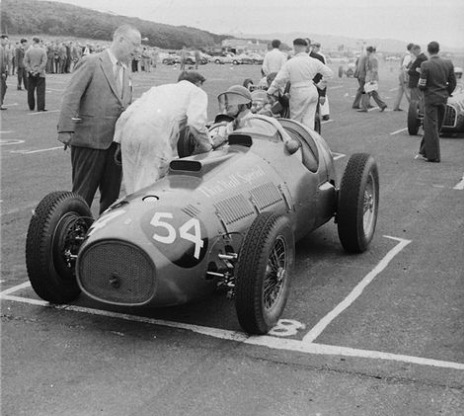

Peter Collins, then 22, at the wheel of the original Vanwall Special ‘01′, ‘Goodwood Trophy’ in September 1954. He qualified and finished 2nd to the Moss Maser 250F (Louis Klemantaski)

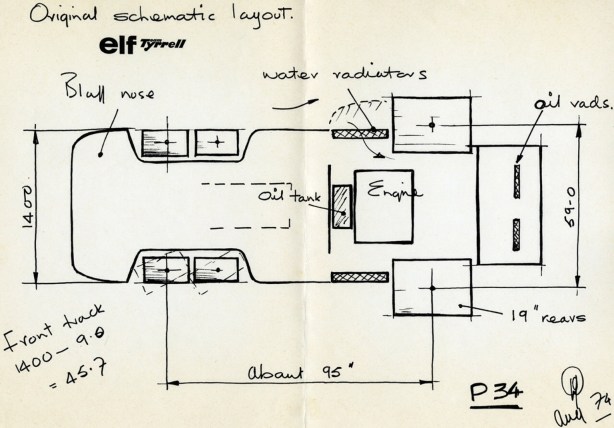

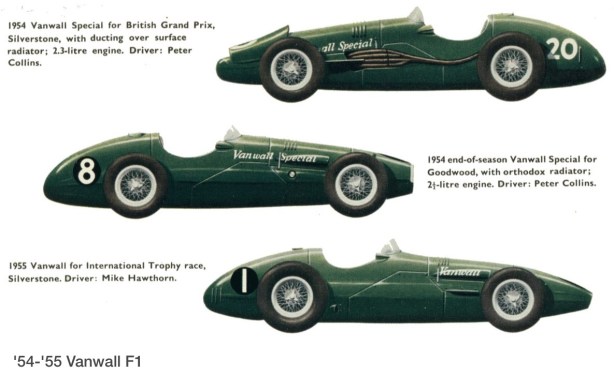

In 1954 the Thinwall Specials became a Vanwall Special…

The name was an acronym of Vandervell’s Acton based ‘Thinwall’ bearing company and his surname. The chassis was designed by Cooper’s Owen Maddock and built at the companies Surbiton factory (given the Type 30 designation retrospectively). The machine had Ferrari inspired suspension and steering components together with a Ferrari 4 speed gearbox modified by VP. Goodyear disc brakes were used, as on the Thinwall, the interesting bit at this early stage was the heart of the car- its engine.

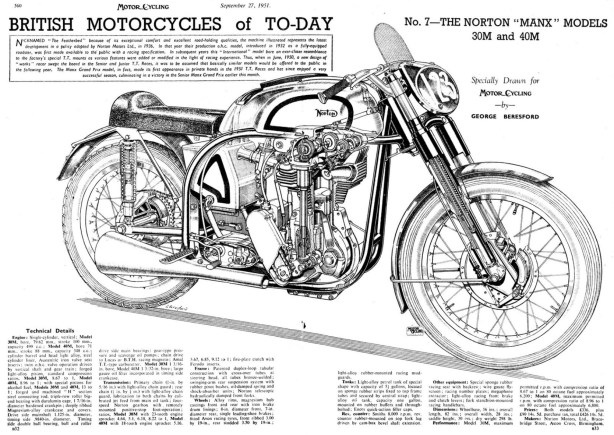

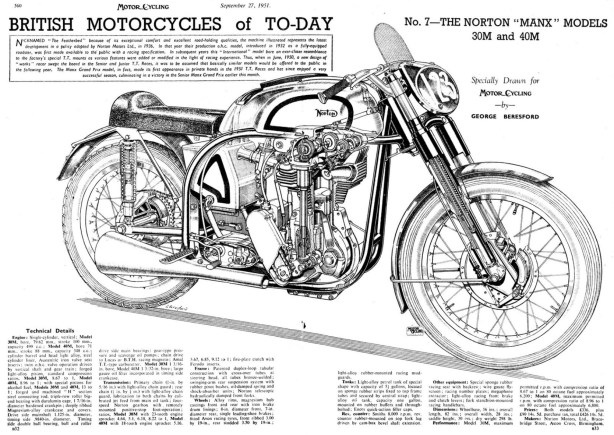

Vandervell became a member of the Norton Motors Ltd Board in 1946 and was naturally impressed by their very successful 500cc single but he felt the company needed to develop a multi-cylinder engine to combat the Italians and contracted BRM’s design arm, Automotive Developments Ltd to design a 500cc four-cylinder engine for Norton. BRM experimented with a water-cooled version of the Norton 500cc single which developed more power than the air-colled original- the design was to be significant in 1954 when Vandervell sought an engine for his new car.

Technically minded and interested, TP had spent plenty of time in the Norton test house with Chief Engineer Joe Craig and Polish Design Engineer Leo Kuzmicki as they developed their latest 500 singles which developed 45bhp on 80 octane fuel in 1951. TP could see how four times that amount and a bit more given alcohol based fuels were allowed in the new 2 litre F2 would be competitive. Additionally the BRM 500 test engine gave 47bhp on test whereas at the time Norton’s air-cooled motor gave 44.2bhp- and so the die was set.

Norton were prepared to help with the head design, Eric Richter, who had worked on the Norton project at BRM, joined Acton from Bourne in late 1950 so Fred Fox and his team were tasked to do the overall engine design, working closely with Craig and Kuzmicki at Norton on the the head and valve gear with specialist tradesmen in milling, grinding and turning seconded from VP to Vanwall Racing- with the coming change to F1 from 2 to 2.5 litres in 1954 the design was to be capable of taking that jump in capacity.

And so it was that the Vanwall engine was essentially the same as the Norton/BRM water cooled single- four Norton single cylinder barrels spigoted into the cylinder head and crankcase, integrated ‘en-bloc’ with added on non load-bearing water jackets.

The bore and stroke of the 2 litre motor mirrored those of the 1952 Norton 500- 85.93cc X 86mm for a total capacity of 1995cc. This double overhead camshaft cylinder head used twin inclined valves in each combustion chamber with motor cycle style hairpin valve springs.

The engine had a deep crankcase into which the four cylinder barrels were spigoted atop which sat the shallow cylinder head casting. Both these key components were held together by ten long, threaded high-tensile steel rods which passed through the head, beside the barrels and through the crankcase and main bearing caps and were secured at each end with nuts.

In the interests of time the team were looking at proprietary crankcases they could adapt to their needs, the ‘winning choice’ was made by TV’s eldest sone Anthony, who had been apprenticed at Rolls-Royce and suggested the four cylinder variant of the R-R B Series military engine, the ‘B40’. This engine was of aluminium ‘F-head’ configuration- overhead inlet valves and side exhaust valves, the five main bearing crankcase was made of cast iron and its capacity when fitted to the Austin Champ military vehicle was 2838cc.

An order was placed for a crankcase cum block in February 1952. Later Leyland were approached- who were making the engine under contract for Rolls-Royce to supply a set of patterns and baked cores for suitable modification.

Vandervell machined a B40 crankcase to their needs as a pattern, together with the cores provided by Leyland to cast a prototype crankcase in aluminium- plenty of work was required by VP to increase the wall thickness to allow for the reduced strength of the alloy to be used and to incorporate the change from five to four main bearings.

The choice of the change from five to four main bearings was thought to be due to savings in weight and friction- Ron Rex in his wonderful series of 8W Forix articles on Vanwall engine design points out that Richter had worked with Stewart Tresilian at ERA and BRM- he was a strong proponent of the use of four main bearings in four cylinder race engines inclusive of BRM”s successful 2.5 cylinder four which raced in the P25 and P48 GP machines from 1953 to 1961.

The crankcase was cast by Aeroplane and Aluminium Castings Ltd of Coventry in RR53B aluminium, the engine used a forged crankshaft machines by Laystall with Vandervell ‘Thin-Wall’ copper-lead-indium bearings used. The wet cylinder barrels were made of cast-iron with the surrounding water-jacket made of RR50 aluminium again by ‘Aeroplane’. The engine was of course dry-sumped with two gear type oil pumps- a triple pinioned scavenge pump and single pressure pump housed in a casting fixed to the front of the engine below the crank.

Vanwall 4 cylinder, DOHC design. Of note are the hairpin valve springs, the train of gears to drive the cams and auxiliaries and high pressure fuel injection pump- at the front of the engine (Vic Berris)

Vanwall engine in 1958 (Jesse Alexander)

The head was to all intents and purposes the latest Norton 500 head with the combustion chamber, ports and valve sizes identical- similarly Harry Weslake’s changes to the Norton heads to promote swirl were also adopted. The inlet and exhaust valves were inclined at an included angle of 64 degrees, as per the works Norton of the time- the inlet ports were 44.5mm in diameter and the exhausts 39.4mm in diameter.

Annular recesses were incorporated into the head into which the barrels were spigoted, around thess were Wills pressure ring copper gaskets. Twin plugs were used (the Norton single had only one), the head was quite shallow as the two camshafts were carried in separate housings on steel pedestals 40mm clear of the head.

The cam housings were open top magnesium boxes capped by beautiful flat plates secured by many screws, the cams were driven off the crank by a train of spur gears contained in a magnesium casting bolted to the front of the engine, an outer gear case provided drives for the magnetos and fuel pump.

Carburetion was provided by four motor cycle type Amal 3GP’s probably with throat diameters of 49.2mm, air intake trumpets with large radii bell-mouths were ftted to each carb. Fuel injection would come soon enough of course, when Bosch and Vanwall worked together on such a system with Mercedes Benz blessing- there existed an exclusivity arrangement between the two companies. The exhaust system was designed and manufactured with Norton practice in mind but in use a four-into two- into one set up was used- with a single pipe extending to the back of the car.

Vanwall contracted British Thomson-Houston Co to supply magnetos which could fire two plugs at up to 8000rpm, when these were late twin Scintillas were used firing KLG plugs.

It became clear the car/engine would miss the final F2 year of 1953 with development of the 2 litre and design of the 2.5 litre happening in parallel throughout that year, the 2 litre first ran in December 1953, producing 148bhp @ 5150rpm in January 1954. By March 1954 235bhp @ 7500-7600 was claimed.

After extensive testing at the RAF Oldham Airfield the machine made its public debut in the 15 May 1954 International Trophy at Silverstone, driven by Alan Brown.

Brown was fifth quickest in practice, three seconds clear of the other 2 litre cars, second practice was wet and the car was quickest starting heat 1 from the front row for sixth and ran a shigh as fifth in the final before retiring on lap 17 with a broken oil pipe.

After the race the 2 litre engine was removed for further development doing over 20 hours on the dyno but it never raced again as it destroyed itself during edurance testing.

Collins raced the car in the British Grand Prix in July fitted with an interim 2.3 litre engine, this was achieved by increasing the bore to the maximum permissible, Peter qualified on the third row and raced well amongst the other cars until a cylinder head joint leaked forcing his retirement.

The major change to the 2490cc engine (bore nor 96mm) was the adoption of a five, rather than four main bearing crank, the valve incuded angle was also reduced from 64 to 60 degrees. Amal carbs were used initially but work progressed with Bosch on the port fuel injection TV wanted with the German company making a four-cylinder injection pump specifically for the purpose.

Peter Collins The Vanwall Spl during the Goodwood Trophy in September 1954

The first 2.5 litre engine, the third engine built was running on the Maidenhead test-beds by August 1954 with an Italian GP entry planned but the engine dropped a valve in endurance testing so the 2.3 litre engine was used at Monza by Collins, there the car again showed promise despite carburetion problems again. In the race Peter pitted with an oil pressure gauge line leaking but he soldiered on to finish seventh.

The 2.5 litre engine finally made its race debut at the Goodwood Trophy on 25 September.

Peter Collins raced the car into second place behind Moss’ Maserati 250F- the added grunt did expose some chassis shortcomings however, then Mike Hawthorn drove it in the Formula Libre race to fourth.

On 2 October at Aintree Hawthorn was second in the F1 race but retired in the Libre event after Mike spun and ingested dirt into the oil coller causing overheating. Hawthorn commented that real power didn’t come in until after 4500rpm but above that it was quite fast with fluffiness over 7000rpm he put down to fuel starvation.

It was time to test the car in a GP so an entry was made at Pedralbes, Barcelona on 24 October for the Spanish race- the Lancia D50 made its race debut that weekend.

Between Aintree and Pedralbes there was much testing of fuel blends and hairpin valve springs which were breaking- by race weekend the engine was giving good results but Peter Collins crashed in practice, he took on rather a large tree- too badly damaged to be repaired the machine was taken back to Acton. There the team wrote it off- Peter bent the frame severely, broke the de Dion tube assembly and rear suspension as well as destroying the rear three Borrani wheels, one of the side fuel tanks and the rear tank which took most of the impact. Clearly Peter was a lucky boy to walk away, the car was not so fortunate.

Preparations for the 1955 season were now well underway, Don Capps notes by November 1954 there were enough spares to assemble two chassis and that TV had acquired two Milling Machines from Count Orsi for then-thousand pounds and the Maserati 250F rolling chassis ‘2513’ in order that the team could suss one of the very best F1 cars of the time.

David Yorke had been signed on as Team Manager with Mike Hawthorn and Ken Wharton signed to drive the two cars the team planned to run.

The main focus of development was to get the fuel injection working- by February the first of the Bosch pumps had been set up on a test engine- these 1955 engines were given the drawing office type number ‘V254′ (the 1954 engines were typed ’54’) and numbered V1 onwards, whereas the cars were now called ‘Vanwall’ not ‘Vanwall Special’ with the chassis’ numbered from VW1 onwards- four 1955 spec cars were built- VW1-VW4 and were essentially based on the Cooper design which picked up Ferrari suspension and steering.

Mike Hawthorn in the Cooper designed Vanwall chassis VW55, Monaco GP 1955, DNF with throttle linkage problems in the race won by Trintignant’s Ferrari Squalo 625 (Unattributed)

Mike Hawthorn during the 1955 Monaco Grand Prix weekend, Vanwall (Getty)

Harry Schell awaits the start of the 1955 British GP at Aintree with the lads including the chief at far left. #4 is the Luigi Musso Maserati 250F, #20 is Eugenio Castellotti’s Ferrari 625, #8 Andre Simons’s 250F

When fitted with fuel injection the engine weighed 163kg and on a compression ratio of 12.5:1 gave an estimated 270bhp. Much work was done on the cars suspension to improve the handling but Mike Hawthorn was disappointed in testing at Oldham Airfield to still find a big flat spot between 4000-5500rpm- as events proved it would be a very challenging year.

At the International Trophy at Silverstone in May Hawthorn qualified second to Salvadori’s Maserati 250F but retired in the race due to a gearbox oil leak- Wharton pitted with throttle linkage problems and then crashed trying to unlap himself- the car then burst into flames with both car and driver the worse for it.

Only Hawthorn raced at Monaco and Spa with disappointing results- he was 4.5 seconds off the pace of Fangio’s Mercedes Benz at Monaco and 14.9 seconds behind Ascari’s Lancia D50 pole in the Ardennes. A broken throttle linkage ended his race at Monaco and an oil leak at Spa. TV approached Rolls-Royce about the vibration induced throttle linkage failures with R-R suggesting fitment of Hoffman ball bearings in the ends of the control rod.

Mike Hawthorn decamped though, telling David Yorke in animated fashion to ‘shove it’ whilst having a few brews with some friends in Spa’s Pierre Le Grand restaurant, he ‘cancelled his contract’ and refunded some of his retainer to Vandervell, with Harry Schell engaged as his replacement in time to contest the British GP at Aintree in July.

There, Harry and Ken were 3.4 and 8 seconds off Moss’ Mercedes W196 pole time. Harry muffed the start but made up time until he pushed the throttle linkage off its mount, whilst Wharton pitted with an oil leak- Harry then set off in his car but still finished last.

In the wake of the Le Mans disaster many races were cancelled so Vanwall Racing entered some minor British events, whilst Harry won four of them but it was clear a lighter, stiffer and more sophisticated chassis was needed as engine development came along nicely- the first of Schell’s wins at Crystal Palace in July resulted in Vandervell shelving a plan to pop one of the Vanwall fours into 250F ‘2513’…

The team took three cars to Monza in September but again were way off the pace- Harry retired with a broken de Dion tube and Ken when the steel bracket supporting the fuel injection pump fractured.

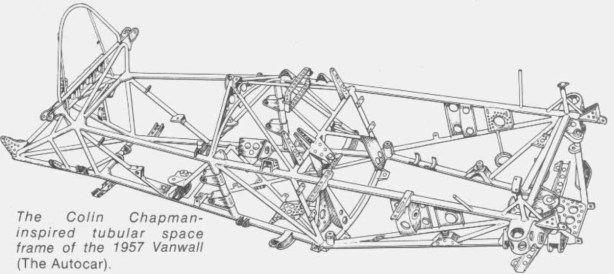

Vandervell’s staff modified the basic Cooper frame and had a mock-up of the proposed chassis for 1956 at which point Colin Chapman was introduced to Vandervell via Vanwall’s transport driver, Derek Wootton, an old friend of Chapman to look at the frame- Vandervell was impressed with Chapman’s knowledge and track record and signed him on to start from scratch rather than evolve the Owen Maddock design.

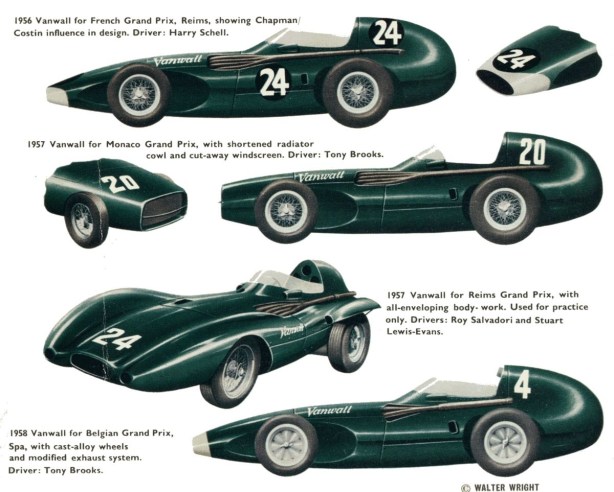

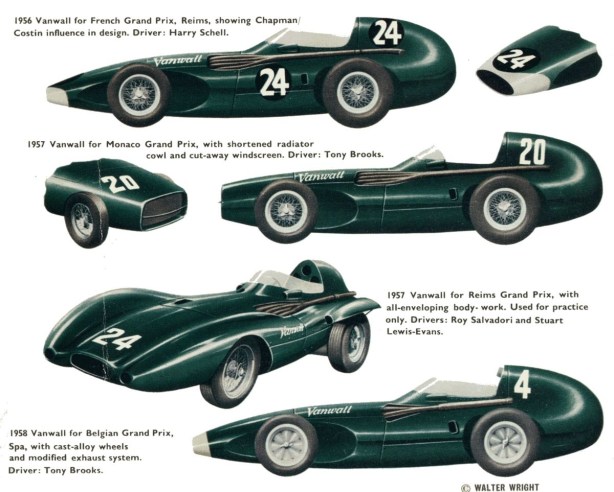

1956 Vanwall…

Moss in the 1958 Dutch GP winning VW10. Shot shows extreme attention to aero for the day by Frank Costin. Borrani wires at front Moss’ preference for driver feel but cast alloy wheels were adopted in 1958 to save weight- this Vanwall, with two GP wins survives today (Copyright JARROTS.com)

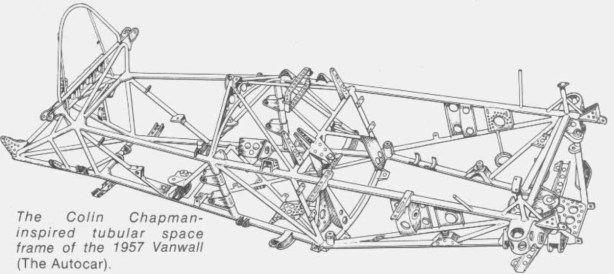

The choice of Chapman, then an up and coming designer and manufacturer of Lotus sportscars in Hornsey behind his fathers pub was a defining moment in Vanwall’s future success. For his first single-seater project Chapman designed a modern multi-tubular spaceframe chassis and engaged aerodynamicist Frank Costin to concept and create the gorgeous, low drag, ultra-slippery body which clothed it.

Chapman retained the 1955 double wishbones and coil spring front suspension, Ferrari derived gearbox and brakes but laid out new de Dion rear axle geometry using a Watt linkage for lateral location whilst retaining the transverse leaf spring.

All four of the 1955 chassis were torn down to form the basis of the four new cars for 1956 which were numbered VW1/56-VW4/56. The new frame featured round section top and bottom longerons of 1.5 inch diameter tube, at the front a sheet metal fabrication (see photo below) provided a cross member for location of the coil and wishbone suspension setup- the frame was complex and rigid weighing only 87.5 pounds.

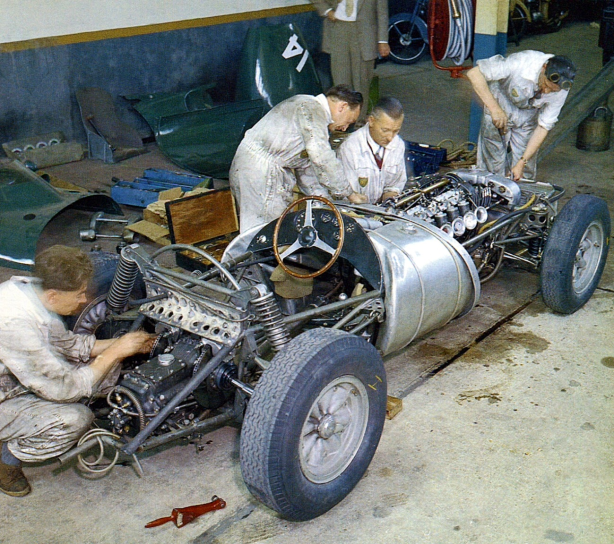

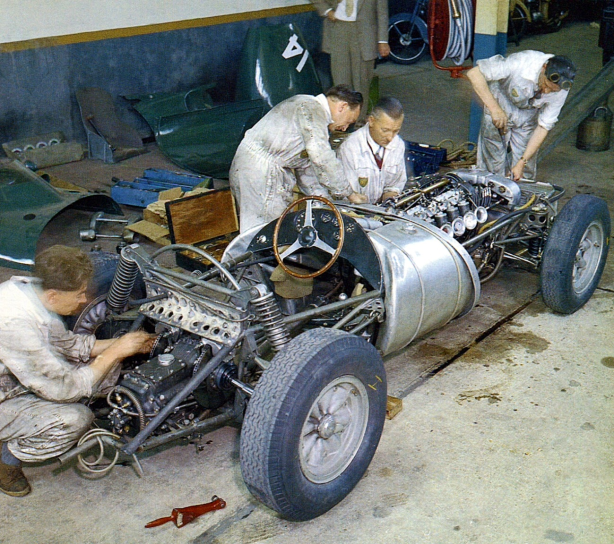

One of Chapman’s new frames coming together at VP Maidenhead plant in early 1956- car behind perhaps one of the 1955 cars being reduced to parts?

High quality of forgings and fabrication of spaceframe chassis evident. Front cross-member visible, steering arm, top link, radius rod, coil spring/damper unit and Goodyear patented disc brakes (Vandervell Products/The GP Library)

Vanwall rear end 1957 with Chapman struts, coil springs and Armstrong dampers.De Dion rear axle with Watts linkage. 5 speed ‘box in unit with diff, see the ducts for the disc brakes. The tail tank is connected to auxiliary tanks mounted alongside the chassis (Automobile Year 5)

Whilst the de Dion rear end was retained the suspension geometry was changed to allow much more negative camber at the rear to enhance the loaded outside tyres adhesion, for 1957 the transverse leaf spring was replaced by ‘Chapman Struts’, coaxial coil springs and locating links.

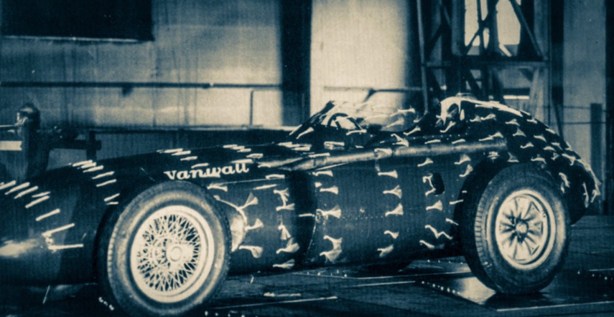

The most striking feature of the car was its Costin designed, teardrop shaped body. Painstaking attention was devoted to underbody fairing, the elliptical body section was designed to minimise deflection in cross winds and drag. Flush ‘NACA’ ducts were used and the distinctive tall headrest faired a 39 gallon fuel tank with two subsidiary 15 gallon tanks located low on each side of the scuttle.

Engine development continued under Kuzmicki’s direction with Harry Weslake’s oversight, TV focused them on camshafts, cylinder head design, fuel injection control and exhaust systems. New cylinder heads were being cast by Aeroplane and Motor Aluminium Castings the key element of which were larger inlet valves. The power curve of the engine was now much broader than the year before with maximum torque of 218 lb/ft developed at 5000rpm with plenty of punch from as low as 4000rpm, maximum power was 276bhp @ 7300rpm.

The best of everyting was used throughout the machine- Bosch fuel injection, Goodyear disc brakes, Mahle pistons, Porsche designed 5 speed synchromesh gear set for the Ferrari designed gearbox cum final drive- Vandervell didn’t get hung up on the whole ‘only British BRM thing’, simply buying the best when he could not readily or cost-effectively build it.

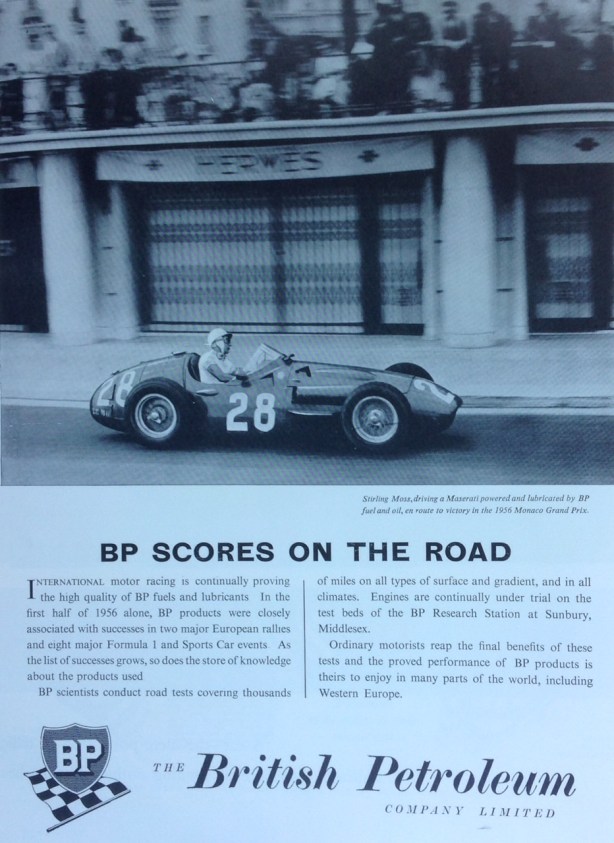

Harry Schell was joined by Maurice Trintignant that season. The team missed the British season opening non-championship events at Goodwood and Aintree in April but Moss raced one of the cars at the 5 May Silverstone International Trophy, as Officine Maserati, Moss’ team in 1956 had not entered the event- he set fastest time and won the 175 mile race which included amongst a big field the works Lancia-Ferraris of JM Fangio and Peter Collins in a tremendous start to the season. Moss was sufficiently impressed to make himself available whenever he was not bound to Maserati.

Harry Schell, Vanwall VW56, Belgian GP Spa 1956 (MotorSport)

Moss during and after the 1956 Silverstone International Trophy win, Vanwall. Note Colin Chapman third from the left, who are the other fellas in shot? (Getty)

Harry Schell with a smile upon his face as Taffy von Trips susses out the Vanwall, DNF for Harry and DNS practice prang for the Ferrari driver- Italian GP 1956. Moss won in a 250F. #26 is the Collins/Fangio second placed Ferrari 801

From that point 1956 demonstrated that the Vanwalls were acquiring the pace they needed to win- straight line speed good and traction out of slow corners but reliability and high speed roadholding were to be areas of focus over the winter of 1956-1957.

The team missed the Argentine opening championship round but at Monaco the cars qualified Q5 and Q6- Schell and Trintignant respectively, Harry had an accident on lap 2 after Fangio made a rare mistake upfront and Harry and Luigi Musso were unable to get through and hit the haybales and Maurice had overheating problems as a result of damage to the nose, the cylinder head cracked so he failed to finish.

At Spa they were Q6 and Q7, Schell finished fourth in the race won by Peter Collins’ Lancia-Ferrari D50, encouraging for Vanwall but the car was a long way adrift of the leaders, deficiencies in handling on high speed corners was readily apparent, whilst Trintignant retired with fuel injection mixture problems which caused a misfire.

At Reims Maurice raced the Bugatti T251, an experience which no doubt reinforced the promise of his Vanwall if not its reliability to this point!- Schell was Q4 and DNF engine, he missed a shift due to gearbox problems but then took over Mike Hawthorn’s car, who was having a run with Vanwall on loan from struggling BRM.

Harry caught the leading Ferraris in a splendid display until he had a problem with the fuel injection control rod linkage which caused him to pit but he was still tenth in a plucky, fast display which endeared him even more to his mechanics- Harry was a popular boy at Vanwall. Colin Chapman- tasting the fruits of his labours missed the cut after a collision in practice with Hawthorn when he locked a brake going into Thillois and hit Mike up the chuff.

(Unattributed)

Silverstone was next with hopes of a good result at home dashed- both the regular drivers failed to finish with fuel system problems- fuel starvation caused by blockages which was later traced to the sodium silicate used to seal the fuel tanks when manufactured. Schell had started well from Q5 whilst Trintignant was Q16 and guest driver, Froilan Gonzalez- always quick at Silverstone with Q4 failed to get off the line with a broken universal joint in one of the half-shafts- Fangio won in a Lancia-Ferrari D50.

The team missed the Nürburgring with insufficient time to prepare the cars but were back again for Monza, the final round of the championship where Fangio and Ferrari won the titles but where all three Vanwalls retired- Piero Taruffi- Q4 and oil leak and Schell Q10 held second place for quite a while before suffering gearbox failure whilst Trintignant, Q11 was out with a broken front spring mount.

The ultra slippery shape of De Havilland aerodynamicist Frank Costin’s body is shown to good effect in the shot above of Stuart Lewis-Evans at Rouen in 1957. Its practice for the French GP, he retired with steering problems. Brooks and Moss absences gave him his chance in several events, he was quick and reliable, Vandervell signed him on as the teams third driver.

1957 and 1958…

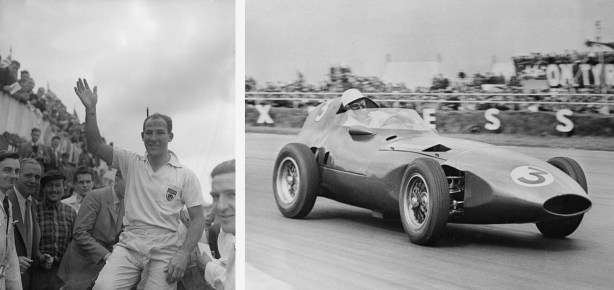

Tony Brooks, winner of the Belgian GP at Spa 1958. Pictured here at Eau Rouge. Chassis is VW5 the most successful ever British front-engined GP car with five wins to its credit, subsequently dismantled and rebuilt around a fresh frame (Unattributed)

Further evolution of the design took place over the winter, the ‘Chapman Struts’ were fitted and Fichtel & Sachs dampers in place of Armstrongs. The engines were teased to develop 285bhp at 7300rpm with an enormous amount of development work devoted to the problematatic hairpin valve-springs, Rolls Royce’ recommendations as to springs being wound from chrome vanadium wire were given to a German supplier S. Scherdel KG to manufacture after the efforts of George Salter and Co and Herbert Terry & Sons in England had still not overcome persistent breakages. Other areas of engine focus were fuel injection pipe and throttle linkage fracture both of which were caused by the big-fours high-frequency vibrations at 4500 and 7000rpm. By this stage the engine numbers ran to ‘V7′, whereas cylinder head numbers were in the forties.

In terms of the chassis’ used during 1957, the four 1956 cars were retained and modified to the latest specifications by a team of eighteen mechanics, Don Capps wrote that ten were planned for the year, his notes on the cars are as follows- VW1, VW2 never completed, VW3, VW4 won the British GP, VW5 won the Pescara and Italian Grands Prix, VW6 was the Streamliner which was converted back to normal bodywork, VW7, VW8 Lightweight chassis, VW9 Lightweight chassis not assembled during the season and VW10.

Moss signed to drive with Tony Brooks as number two- Stirling tested BRM, Connaught and Vanwall’s 1957 offerings at both Silverstone and Oulton Park, on the same days, before making his decision as to his mount for the season, in so doing two critical elements were put in place- an ace in each car.

Tony Vandervell, without sponsors to whom he would have been in part accountable, again missed the season opening GP at Buenos Aires, Argentina on 13 January where JM Fangio won aboard his Maserati 250F in the season in which he took his fifth and final World Championship.

Vanwall did race at the Siracuse and Goodwood non-championship races in April with both cars showing impressive speed. Moss was Q3 Brooks Q4 in Sicily, they raced at the front when an injection pipe to the number 1 cylinder broke on Stirling’s car caused him to pit- he recovered to third but Brooks retired when the water offtake split causing a misfire and overheating which cracked the head- the race was won by Peter Collins Lancia Ferrari D50.

Before Goodwood a fix for the problems of broken injection pipes and throttle linkages was found in the form of Palmer Aero Products ‘Silvoflex’ high pressure rubber fuel lines which would withstand the 450psi of pressure delivered by the Bosch pump to the injectors. Vandervell realised part of the problem was the overhung nature of the injection pump on the front of the engine- which would have been better mounted elsewhere. This did eventually happen when the engine was adapted for the mid-engined car in 1960. ‘Rose Joints’ made by Rose Bros Ltd provided spherical universal joints to fit the throttle linkage which was also part of the fix.

In the Glover Trophy Stirling started from pole only to DNF again with throttle linkage problems- this time the control rod between the throttle linkage and the injection pump control rack broke on both cars. Tony Brooks started from Q2 and was sixth but 5 laps adrift of the winner, Stuart Lewis-Evans won in a works Connaught B-Type, much to Vandervell’s chagrin, watching from the pits, but Stuart would soon be a permanent part of the Vanwall Team.

Vandervell felt that this problem should have been clear in dyno testing but frustratingly happened only when the cars were competing. Palmer were confident their Silvoflex pipe was strong enough in torsion to be used as a flexible joint in the control rod to the injection pump that had broken at Goodwood- it worked perfectly- problem solved.

Whilst all of the above was happening Stirling Moss suggested some engine changes which would sacrifice a little top-end power for greater mid-range torque at Monaco- this was achieved by a change of cams and valve timing- the two race engines for Monaco gave 275 and 276bhp.

Stirling Moss shot off into the lead of the Monaco GP on 19 May but crashed at The Chicane on lap 4- he felt it was the brakes but the team could find no fault after the race- Tony Brooks started fourth on the grid and finished second despite being hit up the rear by Mike Hawthorn’s Ferrari after Moss’ accident. The two scheduled Grands Prix at Spa and Zandvoort were cancelled after squabbles about money.

Vanwall line up at Abbey Panels early in 1957 (unattributed)

Stuart Lewis-Evans on the spectacular, daunting Pescara road circuit in late 1957 (MotorSport)

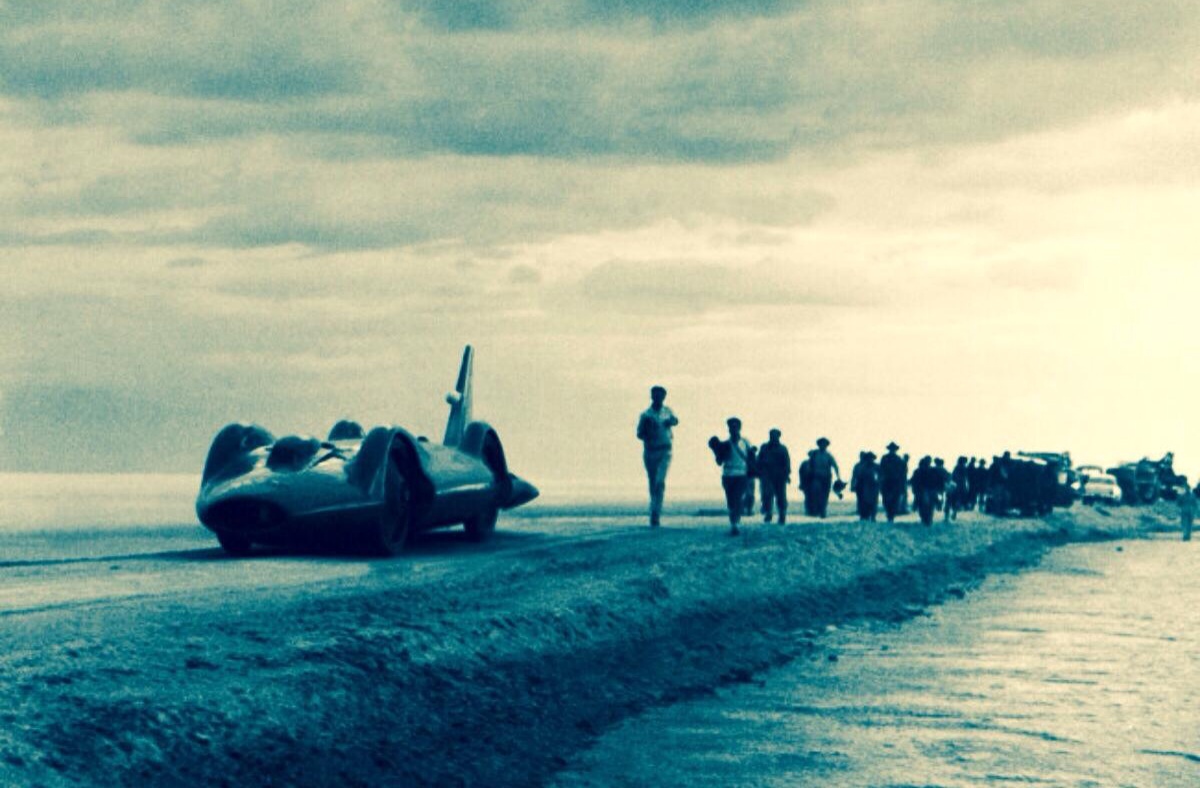

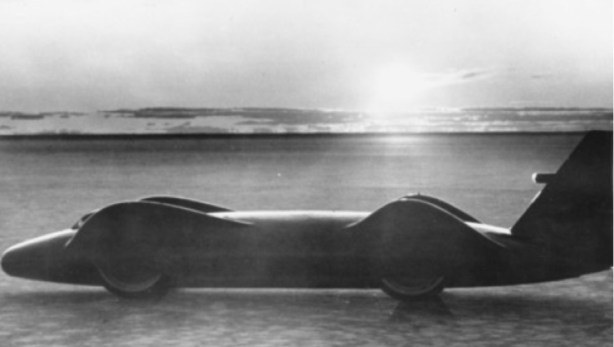

Vanwall tested this ‘Streamliner’, chassis VW6, at the Reims GP in July 1957 in practice. The changes were not successful the increase in weight and ‘sighting’ out of the car not greater than the increase in top speed (Automobile Year)

Rouen-Les-Essarts French GP Vanwall line up 1957- #18 Stuart Lewis-Evans and #20 Roy Salvadori (MotorSport)

The circus next journeyed to Rouen on 7 July for the French Grand Prix where the Vanwall line up was impacted by Moss suffering sinusitis when he inhaled too much salt water whilst water-skiing and Brooks recovering from leg injuries as a result of an Aston Martin accident at Le Mans.

Stuart Lewis-Evans and Roy Salvadori- who had just left BRM were offered the drives and did well in the unfamiliar cars. Roy Q6 and DNF engine valve springs (the German jobbies) after 25 laps and Stuart Q10 and DNF cracker cylinder head in a race won by Fangio in a display of a man at the height of his powers with delicate, majestic high-speed drifts throughout the French countryside.

A week later, still in France the team contested the Reims GP- Q5 and fifth for Salvadori and Q2 only a smidge behind Fangio and third for Lewis-Evans, who led easily for 20 laps until the sustained high speeds on the straights caused piston ring blowby and oil mist escaped from the crankcase breathers affecting his rear brakes and causing him to ease off allowing Luigi Musso’s Lancia Ferrari D50 to win. This impressive, mature performance led to TV signing Stuart as his third driver.

The ‘Streamliner’ body was tried that weekend in practice, its design was supervised by Frank Costin and built by Abbey Panels in Coventry, the detail work including adaptation to chassis VW6 done by Cyril Atkins. Initially the cars gearing was too tall, whilst both drivers tried the car they focused on the normal bodied machines, the body never to be tried again. Clearly the car should have been tried by the regular drivers familiar with the machines rather than ‘newbees’ without a frame of reference.

In the lead up to the British GP four cars were prepared and two spare engines, one of which had a new head which gave more power between 3500 and 5000rpm whilst still giving the same output at 7200rpm. All of the engines were fitted with British Hepworth and Grundage Hepolite pistons after experiments with German Mahles were finally abandoned.

Vanwall finally broke through in that home race, winning their first championship GP on 20 July at Aintree in a car shared by Tony Brooks and Stirling Moss. Moss qualified on pole, led for 22 laps having caught Jean Behra who made a wonderful start, but retired on lap 51 with magneto or plug trouble (depending upon the source), Brooks was summoned into the pits, he had been having a hard time of it with his legs still not perfect after the Le Mans accident, and Moss raced the car to win in magnificent fashion after Jean Behra’s leading Maserati 250F retired with clutch failure. Stuart had throttle control problems and was disqualified and pitted to rejoin the race and finish seventh.

Off to the Nürburgring the team missed the experience of running the prior year- Moss was Q7 and fifth and Brooks Q5 and ninth whilst Lewis-Evans was Q9 and DNF spin and crash after oil from his gearbox breather got on his rear tyres after 10 laps in one of the best Grands Prix ever when Fangio hunted down and passed the Lancia-Ferraris of Mike Hawthorn and Peter Collins.

Two races in Italy rounded out the championship season- on the daunting Pescara road circuit on 18 August and at Monza on 8 September. Moss won from second on the grid on the Adriatic Coast course whilst Lewis-Evans was Q8 and fifth and Brooks Q6 and DNF seized piston after one lap.

At Monza Tony Vandervell finally realised his dream of beating The Bloody Red Cars at home, and to top off Moss win the Vanwalls qualified first to third on the grid in the order Lewis-Evans, Moss and Brooks, Stuart DNF leaking cylinder head core plug but led the race for 5 laps further reinforcing his growing maturity as a driver with Brooks a distant seventh after pitting with stuck throttles.

Given that the Moroccan Grand Prix was a championship round in 1958 David Yorke convinced TV to enter the late October race- there Stuart was second from pole and Tony retired with electrical trouble- a faulty magneto, the race won by Jean Behra’s works Maserati 250F by 30 seconds from Lewis-Evans.

The Bloody Red Cars- that front row in that GP! The three Vanwalls on the Monza front row in 1957- this side is Fangio’s Maserati 250F, #6 is Jean Behra, 250F. Lewis-Evans #20 on pole, Brooks #22 fastest lap and Moss #18 the race winner (unattributed)

Moss’ Vanwall at Silverstone during the 1958 British Grand Prix, DNF engine after 25 laps, Peter Collins Ferrari 801 won (Getty)

Stirling Moss German GP 1958, Vanwall VW4, DNF magneto, teammate Tony Brooks took the win. Vanwall VW4 (Unattributed)

Alcohol fuels were banned for 1958 causing big problems for Vanwall and BRM both of whom used ‘big banger’ four cylinder engines which needed the cooling effect of the alcohol- as a consequence the engine power dropped from 290bhp on alcohol to 278bhp on ‘pump fuel’, to get there is easy to write but was a considerable engineering undertaking.

Changes to the engine involved investigation of cam profiles, three and four valve heads and water injection- changes to port shapes, valve timing and metering cams were the mix of modifications which in the end allowed the engines to get along with less friendly fuel. The Ferrari Dino was reckoned to have circa 286bhp but Italian dynos’ have always been a bit ‘eager’.

Weight saving was investigated but the cars were already light, the rear of the car was also re-profiled slightly by Frank Costin, cast alloy wheels were adopted but often Borrani wires were preferred especially at the front where they gave greater driver ‘feel’.

The chassis used in 1958 were the 1957 machines with detail modifications to the suspension and bodywork. Capps notes, again, as follows- VW1-VW3 and VW8 were not assembled and used for spares, VW4 won the German GP and was destroyed at Casablanca (Lewis-Evans) VW5 won the Belgian, Italian and Moroccan Grands Prix, VW6, VW7, VW9 and VW10 which won the Dutch and Portuguese GP’s.

Given the time taken to make all of the modifications to the engines to meet the new pump fuel regulations, the 19 January Argentine Grand Prix was missed as were the early non-championship events but Stirling Moss made hay whilst the sun shone winning the race in Rob Walker’s Cooper T43 Climax 1960cc against all of the odds and won a famous victory- the first championship win for a mid-engined car.

Moss tested the first of the modified cars at Silverstone at the end of April, well prior to Monaco on 18 May. There Brooks ran in second from pole to Behra’s BRM P25 until he retired when stripped thread caused a spark plug to blow out of the head. poor Behra retired and Moss led (Q8) but retired on lap 38 when a valve cap came off whilst Lewis-Evans retired on lap 12 form Q7 when a warped cylinder head joint failed. Maurice Trintignant won in one of Walker’s Cooper T43 Climax’.

Zandvoort was the following weekend with the three Vanwalls up front- Lewis-Evans from Moss and Brooks. Stirling won despite limiting his revs to 7200 given sagging oil pressure on right-handers, Tony retired after 13 laps with handling problems and Stuart finished 46 laps before a broken valve spring holder intervened.

At Spa Mike Hawthorn was on pole in his Ferrari Dino 246 with Moss Q3, Brooks Q4 and Lewis-Evans Q11. Moss was out on the first lap having muffed a gear, bending valves then Tony Brooks took the lead and battled with the Ferraris to win whilst Stuart was third. It was felt that the Vanwalls had more power on the climb from up from Stavelot but the Ferrari’s higher top speed gave them the edge on the downhill straight to the Masta Kink.

Zandvoort 1958 front row- Lewis-Evans at left on pole, then Moss and Brooks at right (Unattributed)

The Moss, and winning Brooks Vanwalls are pushed onto the Monza grid in 1958- feel the vibe (John Ross)

Brooks at Spa in 1958- alloy wheels front and rear this weekend- he won in VW5 (MotorSport)

Another fast circuit followed- Reims on 6 July. Mike Hawthorn led the race from pole with Moss second from Q6- he was slowed by a misfire between 6400-6800rpm and was down about 10mph to the Italian car in top speed. Brooks retired with valve problems from Q5 after 16 laps and Lewis-Evans was out after 35 laps- a broken inlet valve, he started from grid 10.

In France the Vanwalls were in trouble with warping cylinder heads given the impact of Avgas, two engines dropped valves resulting in pre-race rebuilds. TV had a major standoff with his valve supplier, Motor Components Ltd, given ongoing breakages especially of the sodium-filled inlet valves, that Vandervell Products struck out on their own importing equipment from the US to become self-sufficient by the seasons end.

The Ferraris mid-season renaissance continued at Silverstone where Peter Collins won from Mike Hawthorn. Stirling started from pole, but another broken valve ended his run after 25 laps, Stuart was fourth (Q7) and Brooks seventh (Q9) despite his car having a trip back to Acton to have the head lifted and valves re-ground, with neither ever really in the hunt.

Experiments were ongoing at Maidenhead to try and solve the valve problem with different materials with some spectacular failures taking a toll on the stock of heads, causing a shortage of engines, as a consequence only two cars were entered at the Nürburgring, Stuart was a spectator for the weekend.

Vanwall were much more competitive in Germany in early August than in 1957 when they paid for their absence in 1956, Tony Brooks qualified second and Stirling Moss third. Moss led comfortably from the start going easy on the revs- 7000-7100 when the usually reliable magneto shorted after 3 laps, Brooks took up the chase of Collins and Hawthorn, gaining on the back part of the daunting circuit, passing one after the other under brakes for a rather well- timed win.

Oil coolers were fitted to the front of all three Vanwalls- they were back to full strength at Oporto on August 24 with Moss winning from pole- he and Hawthorn battled for the lead until lap 8 when Mike’s drum brakes began to fade allowing Stirling to pull away. Stuart was third from grid three but Tony spun and was unable to restart from Q5 having completed 37 laps.

At Monza in a marvellous weekend Tony Brooks won the race and with it secured the Manufacturers Championship with one round at Morocco still to run.

Vanwall had transported the cars direct from Portugal to Italy before removing the engines to be rebuilt back in the UK. The oil coolers were still fitted and Stirling tried a Perspex canopy over the cockpit in practice but it only gave 50rpm more on the straight so he elected not to run it- he muffed a shift requiring an engine change too. He battled for the lead with Hawthorn, Mike’s car fitted with disc brakes for the first time but Stirling retired with a seized bush on the gearbox mainshaft. Then Brooks (Q2) pitted because of an oil leak from a burst driveshaft gaiter but nothing could be done so he had to nurse his tyres to the finish, which he did- and took a well judged win despite Hawthorn coming out of the pits in front of him, but his Ferrari was suffering from a slipping clutch. Lewis-Evans retired with overheating caused by a leaking head joint.

The final race of 1958 in Morocco is where we came in…

As stated earlier, whilst Moss missed out on the drivers title to Hawthorn by one point, Vanwall won the inaugural Constructors Championship.

End of The Beginning of Dominance of The Green Cars…

Moss and Vandervell share the spoils of victory, Pescara GP, Italy 1957 (Unattributed)

For Vandervell it was ‘mission accomplished’ and whilst Vanwall raced on they did so without the full campaign of previous years.

Vandervell took the death of Lewis-Evans very hard and his own health was failing given the huge pressure of running his various enterprises. He announced the teams withdrawal from full-time competition on 12 January 1959, they raced four times in the final three years, its swansong was the rear engined Intercontinental Formula car competing in May 1961 at Silverstone.

It wasn’t quite that simple though, many of the key team members were retained, the four cylinder engines still ran on the Maidenhead test benches doing engine research, an advance after the cars last raced were cylinder barrels which screwed into the head solving fire-joint sealing.

Vandervell offered Brooks a retainer to stay with the team in case he decided to change his decision but Tony unsurprisingly raced on with Ferrari but he did race VW5 at the 1959 British GP when a strike at Ferrari meant they did not race at Aintree. He raced a modified version of VW5 to the same general specs of 1958 except that the engine, prop shaft, seating position and bodywork had been lowered and some weight removed- in addition more torque had been extracted throughout the rev range but the car was ‘not a shadow of the racing car he had driven in 1958. Even a team as professional as Vanwall could not gear up and suddenly be competitive’ Bill Ben wrote.

Brooks put the car on the third row of the grid but was outpaced in the race with a misfire- he retired, Jack Brabham’s works Cooper T51 Climax FPF took the win- times had moved on.

He also raced the car in the 1960 Glover Trophy at Goodwood for seventh with Brooks advising they were wasting their time on a 1958 design and that they should concentrate on a mid-engined car. To that end a Lotus 18, chassis ‘901’ was bought, the Vanwall engine was mated to the Lotus gearbox, Brooks tested it at Snetterton but work on the front- engine cars continued.

Vanwall engine installation- very neat and cohesive, in Lotus 18 chassis ‘901’ (GP Library)

Tony Brooks in VW11 at Reims, 1960 French GP (Unattributed)

Naked Vanwall VW11 in the Reims paddock 1960 (Unattributed)

Valerio Colotti was hired to design a 5 speed gearbox and independent rear suspension for a new front engined car and to help design a mid-engine machine, Valerio worked in Acton to expedite the process.

Post Goodwood VW5 was modified by fitment of the new IRS- that famous machine, sadly, was then broken up to donate bits for Colotti’s new front-engined machine which was given the VW11 chassis number. This ‘Lowline’ was lighter and lower than the cars which went before and had considerably less frontal area as the gearbox was aft of the driver, he was not sitting atop it as before. The engine was tweaked to give almost 280bhp- no details have been released as to how this was achieved.

Tony Brooks then raced Vanwall VW11 in the 1960 French GP at Reims on 3 July with a less powerful engine fitted.

He qualified the new but still outdated car thirteenth, 6.5 seconds adrift of pole, retiring on lap 7 with a vibration from the rear having been hit up the chuff by another car at the start. That year Brooks drove most of the season in British Racing Partnership year old Cooper T51 Climaxes and was prodigiously fast amongst newer Cooper T53s.

In terms of progress on the mid-engined front, whilst the team proceeded with Vanwall’s own design, Brooks raced the Lotus 18 Vanwall in the September 1960 Lombank Trophy race at Snetterton with the car showing good pace until valve trouble intervened causing a non-start- 280bhp was claimed for this 2.5 litre F1 engine.

(Hall & Hall)

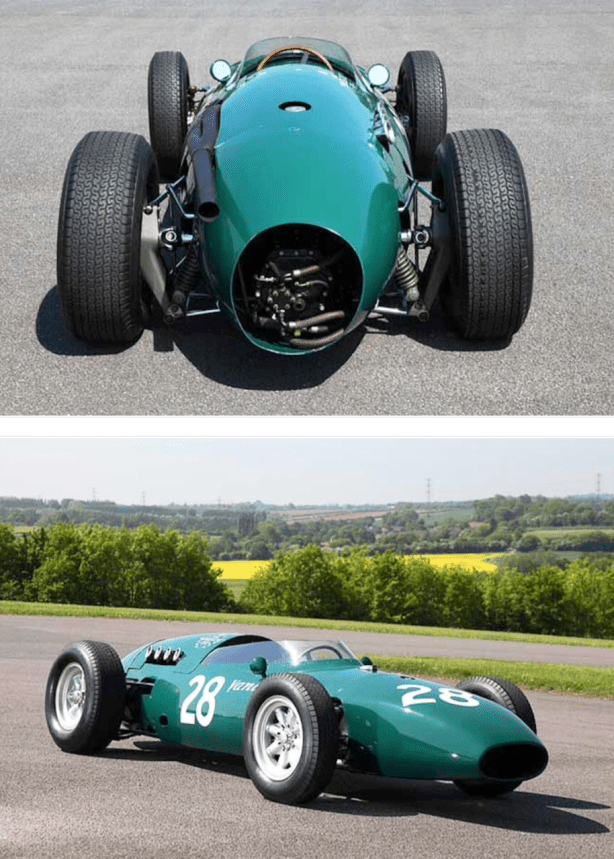

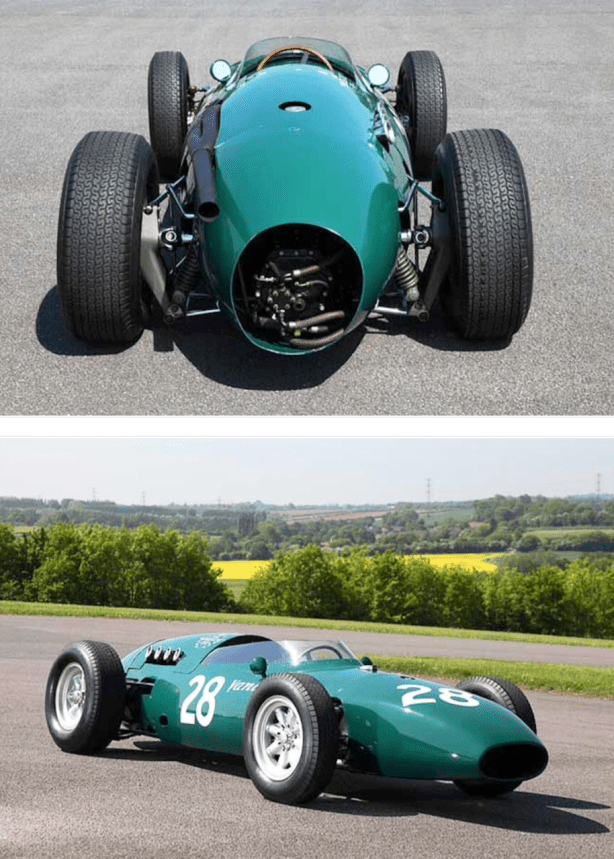

The Vanwall VW14, built for the 1961 Intercontinental Formula, was finally competed in 1961 and finished to the usual standards of Vanwall build quality and presentation.

It was fitted with 2.6 litre Vanwall engine variant and a 5 speed Colotti Type 24 transaxle fitted with VP internals.

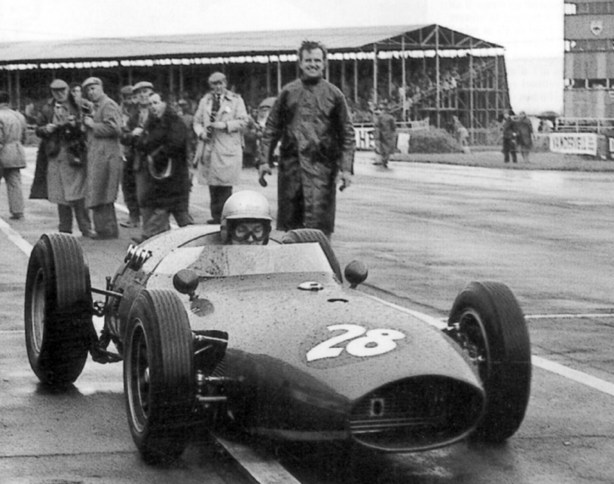

John Surtees was entered in the new car to contest the Silverstone International Trophy Intercontinental Formula meeting on the 6 May 1961 weekend.

After driving the car Surtees expressed the view that the Vanwall engine was potentially better than the all-conquering Coventry Climax FPF but found the fuel injection tricky to set up to avoid flat-spots. He ran second in the race before spinning in the tricky conditions and then had to pit to have debris removed from the radiator- he finished fifth, in this, the final race appearance of a Vanwall ‘in period’.

Stirling Moss won from Jack Brabham and Roy Salvadori, all three aboard Cooper T53 Climax’.

Surtees, VW14, Silverstone May 1961 (Getty)

Vanwall VW14, the very last car. John Surtees at the Silverstone International Trophy in May 1961. He qualified the 2.6 litre engined ‘Intercontinental Formula’ car 6th, ran second, spun and finished 5th in Vanwalls’ last race as a factory team (Unattributed)

VW14 was entered in the British Empire Trophy race at Silverstone on 8 July with Jack Brabham at the wheel when Surtees’ team, Yeoman Credit, refuse to release him for the race- Jack did good times in practice but declined to race the car as he didn’t like its handling. What a shame Vanwall did not get the benefit of some chassis development sessions overseen by Brabham! With no other top-liners available Vandervell withdrew the entry, and that, sadly, was that.

A final note in terms of the chassis count in the concluding years of the race program, again using information from Don Capps’ 8W Forix piece.

At the end of the 1958 championship winning season three chassis were retained and the balance broken up- VW5 was rebuilt as we have just covered, VW9 was kept as a show car by VP and VW10 was used for testing purposes but rebuilt in 1960 to 1958 specifications for demonstration purposes.

VW11 was a new car built from VW5 components as a ‘Lowline’ and after being raced by Brooks was dismantled and retained by the team. VW12 was the Lotus 18 chassis ‘901’ which was sold as a rolling chassis, and VW14 was the mid-engined Intercontinental Formula car raced by John Surtees, then rebuilt as a Mk2 variant but never raced in that form and ultimately restored as raced by Surtees at Silverstone.

Vanwall VW14 Mk2 Intercontinental as shown in a contemporary press shot- the car was unraced in this form (Vandervell Products)

Etcetera and somewhat at random- Thin Wall and Vanwall…

(goodwood.com)

GA Vandervell with Giuseppe Farina during the 1952 Goodwood Trophy weekend on 27 September 1952. Ferrari 375 Thinwall Spl – DNS the feature race but did finish second in the ‘Woodcote Cup’ 5 lapper behind Froilan Gonzalez’ BRM V16 who also won the feature race from Reg Parnell’s BRM.

(John Ross)

Journalist/author Graham Gauld points the direction of Aintree travel to Stuart Lewis-Evans during the 1957 British GP. Bucket, spade and pile of dirt to deal with fires and errant pools of lubricant/coolant. Interesting shot, i like it.

(MotorSport)

Tony Brooks, second place at Monaco in 1957, beautiful shot Quayside- Vanwall VW57, Fangio won in a Maserati 250F.

(Unattributed)

Moss on the hop using all the Aintree road and a little bit more during the wonderful 20 July 1957 British GP in which he shared VW4 to win the race together with Tony Brooks- the first championship GP win for Vanwall.

(Unattributed)

Moss and Lewis Evans after the finish at Aintree in 1957- must be a parade lap as Stuart’s race ended after completing 82 laps and Tony Brooks below in VW4 before handing it over to Moss.

(MotorSport)

Nino Farina winning the Formula Libre support race during the 18 July 1953 British GP meeting at Silverstone- Ferrari 375 Thinwall 4.5 V12.

Farina won from the two BRM Mk1 P15 V16s of JM Fangio and Ron Flockhart- the Italian finished twelve seconds in front of Fangio in the 17 lap half hour race. Vandervell’s Thin Wall plan plan was in part to give BRM a competitive car to race against when he acquired the first Ferrari, over the ensuing years he certainly achieved that aim!

Note the disc brake on the left-front, it would be a while before the factory cars went down this path…

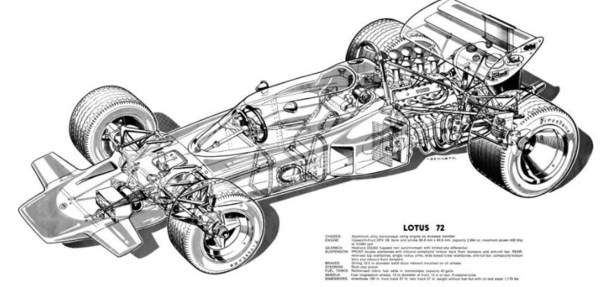

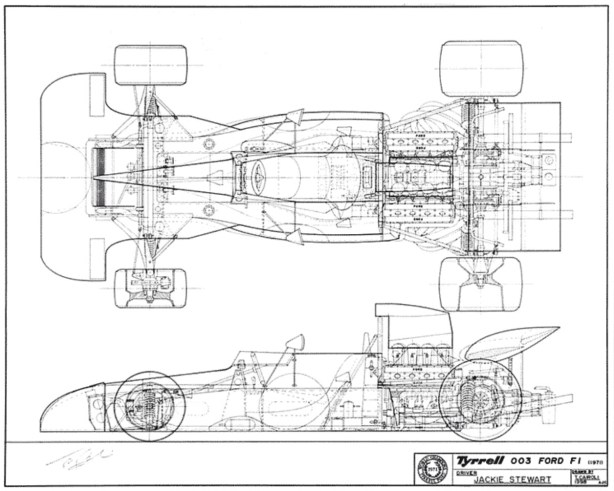

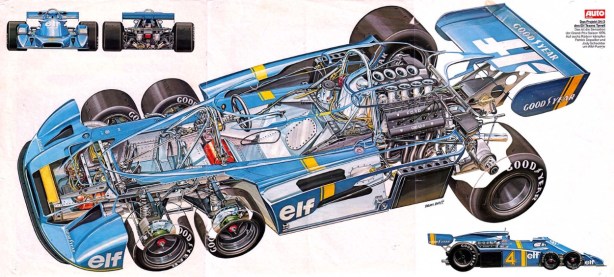

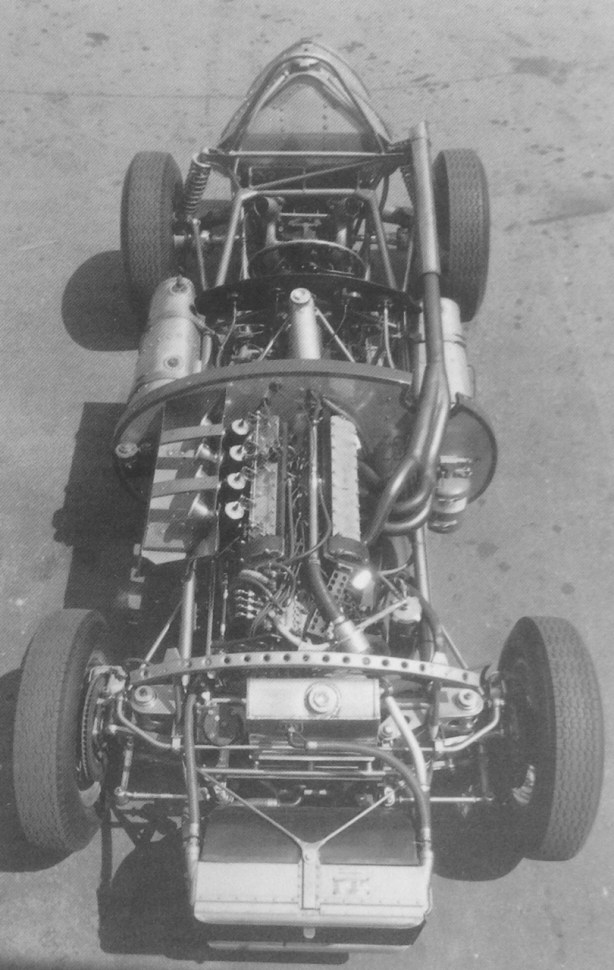

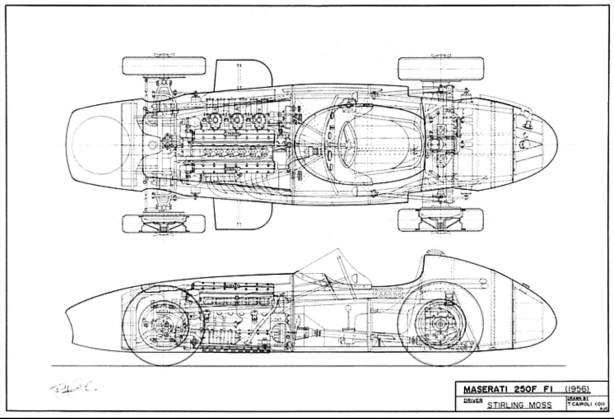

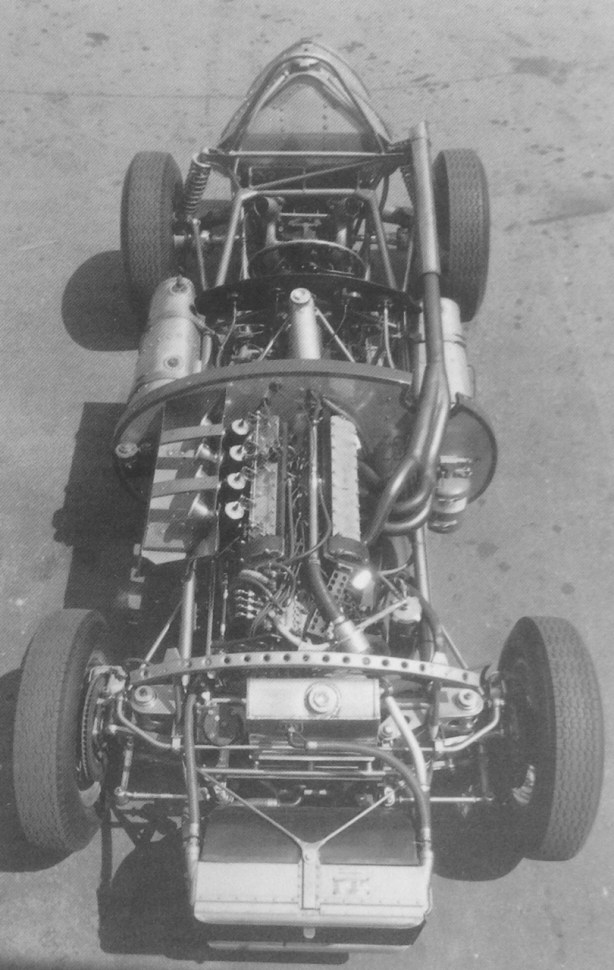

(Doug Nye ‘History of The Grand Prix Car’

Vanwall VW10 ‘stripped’.

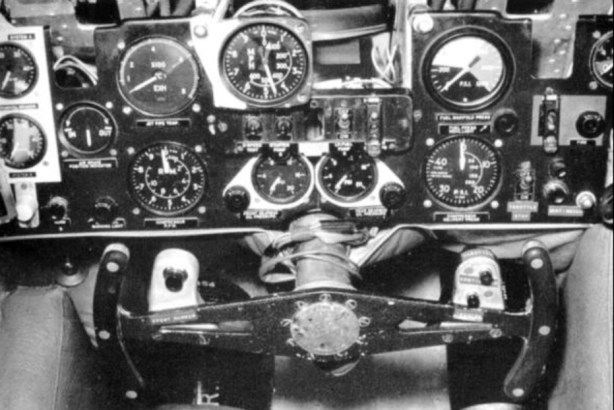

Chapman spaceframe chassis, four cylinder DOHC engine, tail and cockpit fuel tanks, under-seat transaxle, this 1957 car has Chapman struts at the rear- further technical details as per the text.

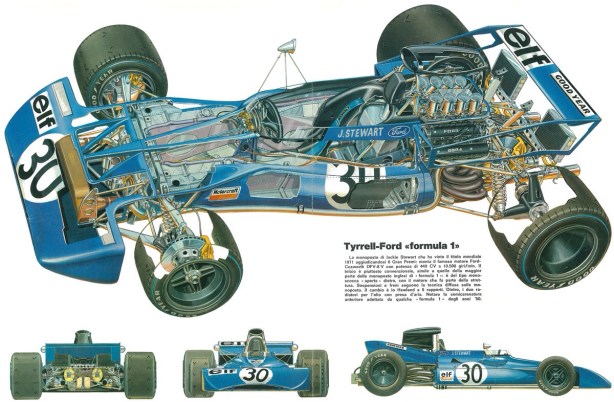

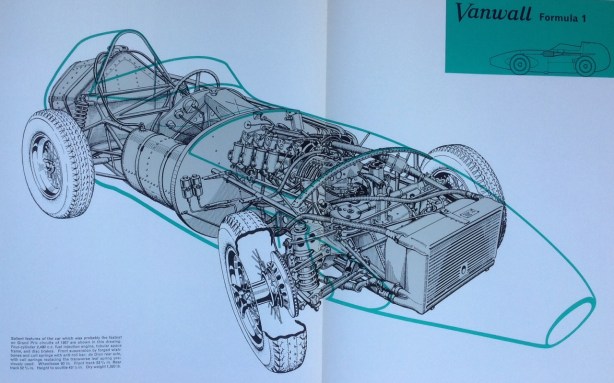

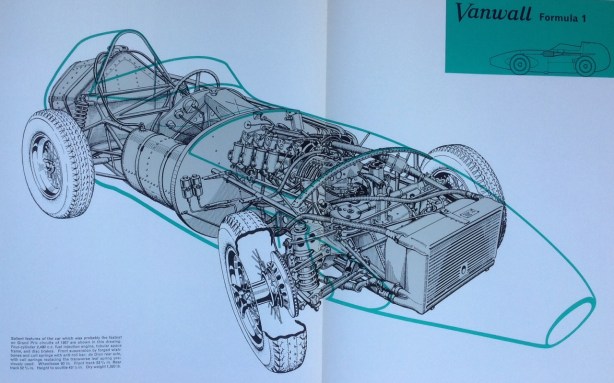

James Allington period cutaway drawing of the car as raced in 1957 and published in ‘Automobile Year 5’

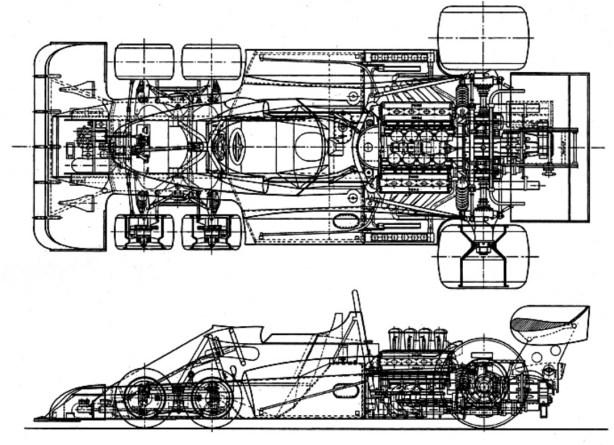

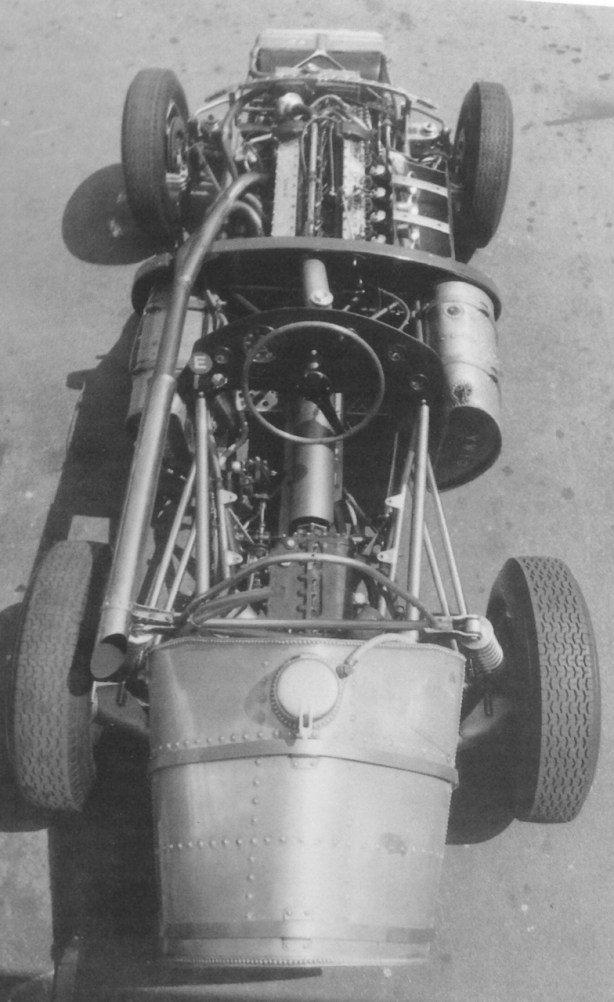

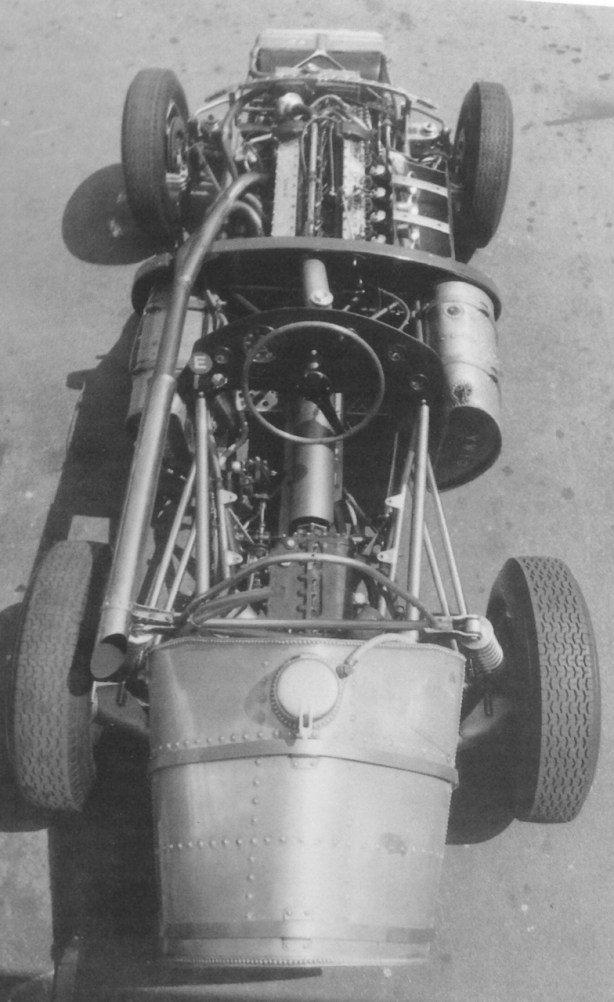

(Doug Nye “History of The Grand Prix Car’

Vanwall VW10.

Ferrari derived transaxle, cockpit layout, rear and twin side fuel tanks and radius rods to locate rear suspension fore/aft all visible, again, further technical details as per text.

(MotorSport)

Mano e mano- first lap of the 1957 Monaco GP with Fangio’s Maserati 250F from pole in front of the Moss Vanwall on the outside and Peter Collins’ big Ferrari 801 menacing from the inside- first, DNF accident times two the outcome.

(MotorSport)

Harry Schell dives into La Source at Spa in 1956, Vanwall VW56- he was fourth in the race won by Peter Collins Lancia Ferrari D50 from local boy, Paul Frere’s similar car.

(Automobile Year)

The Reims ‘Streamliner’, chassis VW6, was tried in practice only during the French GP weekend in 1957. I wonder what, precisely, the difference in lap times was? Attractive up front, not so much so at the other end where the design does not look so fully resolved. Ferrari 801 in the background.

(Unattributed)

Cockpit by the standards of the day is comfortable, swivelling face level vents to keep the driver alive in the carefully faired space, the gearbox notoriously difficult to use. The car was very fast but not as forgiving to Moss as a 250F. Car needed the best to get the best from it. This is chassis VW9 in modern times.

(Unattributed)

John Surtees in VW14 during the rather damp Intercontinental Formula Silverstone International Trophy in May 1961- second place, a spin in the wet, finished fifth in the race won by Stirling Moss’ Rob Walker Cooper T53P Climax.

(Getty-Keystone)

Alberto Ascari races the Ferrari 125 V12 s/c Thinwall during the 26 August 1950 Silverstone International Trophy meeting. Alberto did not start the final after an accident in heat 2- Giuseppe Farina won it in an Alfa Romeo 158.

(Unattributed)

The Vanwall Team in the Monza paddock 1957- Moss won the Italian GP in ‘VW5’.

I’ve done the cutaway drawings to death in this article! But here is another variation on the theme, artist unknown- inclusion of the brackets does emphasise just how many attachment points there are!

(Unattributed)

Stirling Moss hooks his Vanwall into a fast left-hander on the Adriatic Coast course out of Pescara during his victorious 1957 Grand Prix drive.

(John Ross)

Stuart Lewis-Evans, with perhaps a tad more understeer than he may want, from Harry Schell, BRM P25 during the 1958 British GP at Silverstone- fourth and fifth place battle, Peter Collins and Mike Hawthorn were up front in Ferrari 801s.

I wonder what Harry thought of the merits of the two four cylinder British GP cars of the later 2.5 litre F1 period- ‘his’ Vanwall and BRMs?

(The Cahier Archive)

This shot shows the relative height of the Vanwall, which was very tall, the driver sitting atop the drive-shaft.

Fangio is alongside and in his last grand prix in a works-Maserati 250F ‘Piccolo’ and finished fourth. Moss in VW 10 was second in the race won by Hawthorn’s Ferrari Dino 246- French GP, Reims 1958.

(Unattributed)

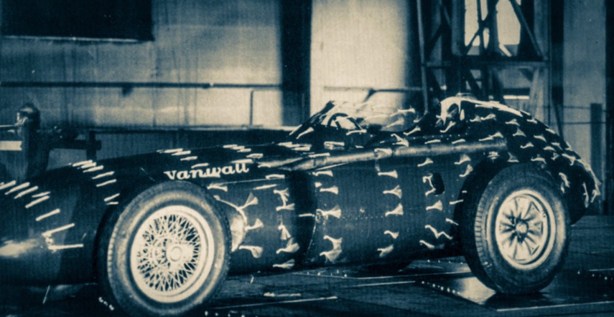

Aerodynamic testing of during 1958- I wonder which wind-tunnel was used for the purpose? Note the wire/alloy wheel combination being tested.

(Unattributed)

A spot of tea at what appears to be a Silverstone test session, circa 1957, Moss up.

(goodwood.com)

Peter Collins bustles his Ferrari 375 Thinwall into Madgwick at Goodwood in 1953- he set lap records in the car in the June and September meetings that year at 1:32.6- 93.30mph and 1:32.2- 93.71mph.

(J Saltinstall)

Oporto, Portugal 1958- Moss, Hawthorn, Ferrari Dino 246 and Jean Behra, BRM P25. First, second and fourth in the Portuguese Grand Prix.

Etcetera: Moroccan GP 1958…

(Unattributed)

Too many great photos, so lets not let them go to waste. Mike Hawthorn, Ferrari Dino 246.

(Unattributed)

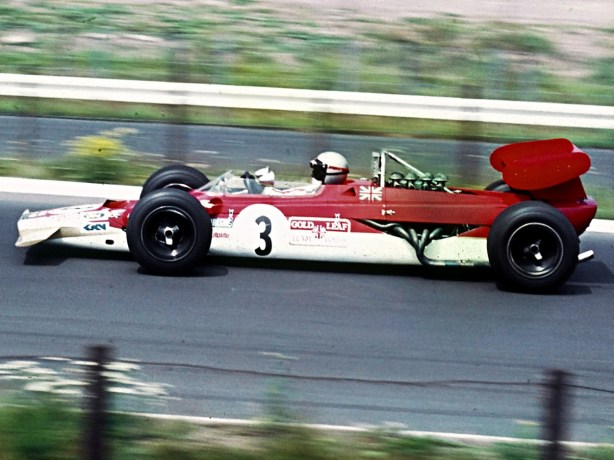

Graham Hill finished sixteenth and last in the Lotus 16 Climax, whilst his teammate Cliff Allison was tenth in the earlier Lotus 12 Climax.

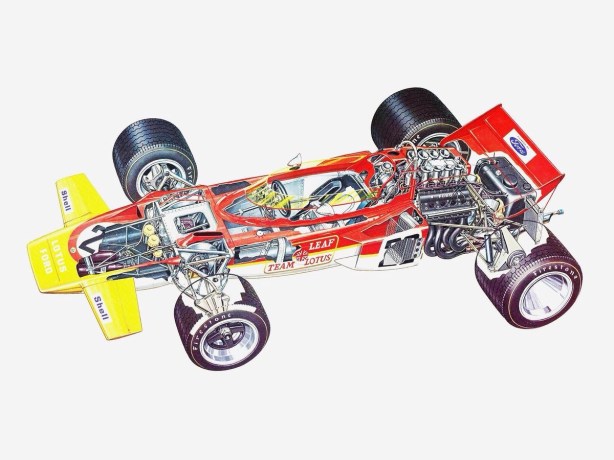

The Lotus 16 was also designed by Colin Chapman and immediatley branded the ‘Mini Vanwall’, the same concepts were applied by Chapman and Frank Costin who did the aerodynamics.

The car was much lower than Vanwall, the engine was ‘canted’ in an offset way to allow the driveshaft to be located beside the driver rather than him sit atop it. But the Coopers had arrived, the Lotus 16 was an ‘also ran’ in 1959, whilst the Lotus 18, when Chapman applied himself to the mid-engined approach then vaulted the marque forward.

(Unattributed)

Masten Gregory was a great sixth in the by then ageing Maserati 250F .

(Unattributed)

Stuart Lewis-Evans in Vanwall VW4 on that sad day at Morocco 1958.

Photo Credits…

The Cahier Archive, Stirling Moss Archive, The GP Library, Walter Wright Illustrations, Louis Klemantaski, The Autocar, James Allington cutaway drawing, Jesse Alexander, Automobile Year 5, Stephen Dalton Collection, Vic Berris, Hall & Hall, Getty Images, JARROTTS.com, Motor Cycling September 1951, MotorSport, John Ross Motor Racing Archive, goodwood.com, John Saltinstall Collection, GP Library

Bibliography…

‘8W Forix’ Vanwall articles by Ron Rex and Don Capps which are linked early in this piece, ‘The History of The Grand Prix Car’ Doug Nye

Tailpieces…

(MotorSport)

Tail shot for the tailpiece…

Tony Brooks’ Vanwall chasing Ron Flockharts’ BRM P25 during the 1957 Monaco classic, not a lot of time to take in the quite stunning view I guess. Tony was second behind Fangio’s 250F whilst Ron’s engine cried enough after completing 60 laps.

Finito…