Ferrari have been fantastic this year, as they often are in seasons of a new F1 formula. Mark Bisset analyses that notion and calculates the Maranello mob’s likely chances of success…

Aren’t the 2022 F1 rules fantastic! The FIA tossed the rule book up in the air – in a highly sophisticated kind of way of course – and it landed as they hoped with a few long overdue changes in grid makeup.

Ferrari up front is good for F1, anyone other than Mercedes will do, their domination of modern times has made things a bit dreary.

It’s way too early to call the season, but two out of four for Ferrari has promise given the budget-cap. “It’ll be ten races before McLaren have their new car. And it won’t be all new, that’s not possible within the budget constraints,” Joe Ricciardo told me on the morning of the AGP.

By the end of the season, the new-competitive-paradigm will be clear to the team’s Technical Directors, next year’s cars will reflect that. In the meantime, we have great, different looking cars the performance shortcomings of which can be addressed, to an extent.

For many years Ferrari was a good bet in the first season of a new set of regulations, let’s look at how they’ve gone since 1950 on the basis that history is predictive of the future…

Enzo Ferrari ran a family business, while he was technically conservative and kept a wary eye on the lire, his first championship GP winning car, the Tipo 375 4.5-litre normally aspirated V12 raced by Froilan Gonzalez in the 1951 British GP at Silverstone commenced a new engine paradigm (achievements of the Talbot Lago T26Cs duly recognised).

Since the 1923 Fiat 805 GP winners had been mainly, but not exclusively powered by two-valve, twin-cam, supercharged straight-eights, like the 1950-1951 World Championship winning Alfa Romeo 158-159s were.

Alfa’s 1951 win (JM Fangio) was the last for a supercharged car until Jean -Pierre Jabouille’s Renault RS10 won the 1979 French GP, and Ferrari were victorious in the 1982 Constructors Championship with the turbo-charged 126C2.

When Alfa withdrew from GP racing at the end of 1951, and BRM appeared a likely non-starter, the FIA held the World Championship to F2 rules given the paucity of F1 cars to make decent grids.

Aurelio Lampredi’s existing 2-litre, four-cylinder F2 Ferrari 500 proved the dominant car in Alberto Ascari’s hands taking back-to-back championships in 1953-53.

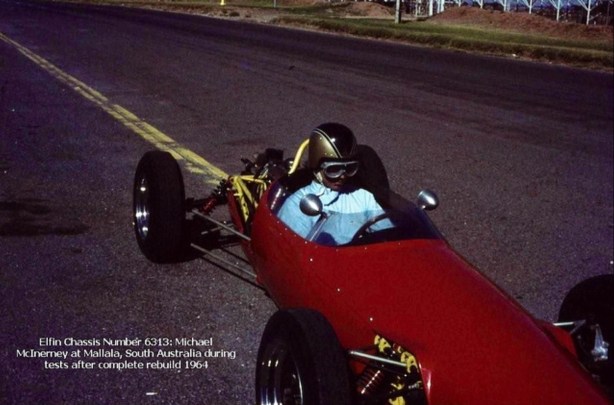

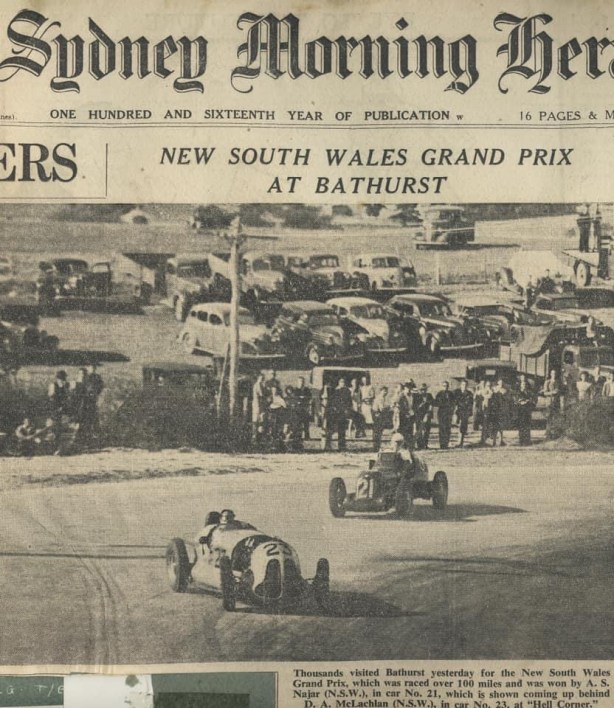

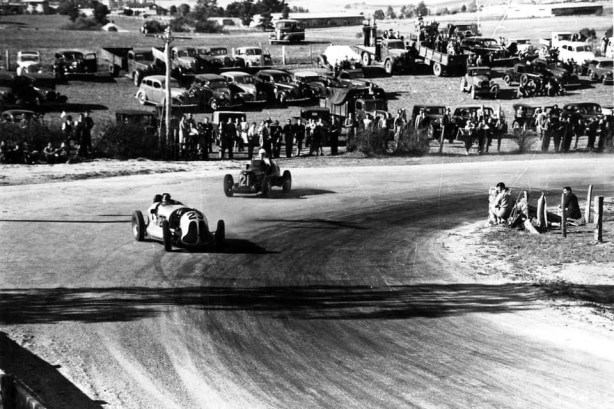

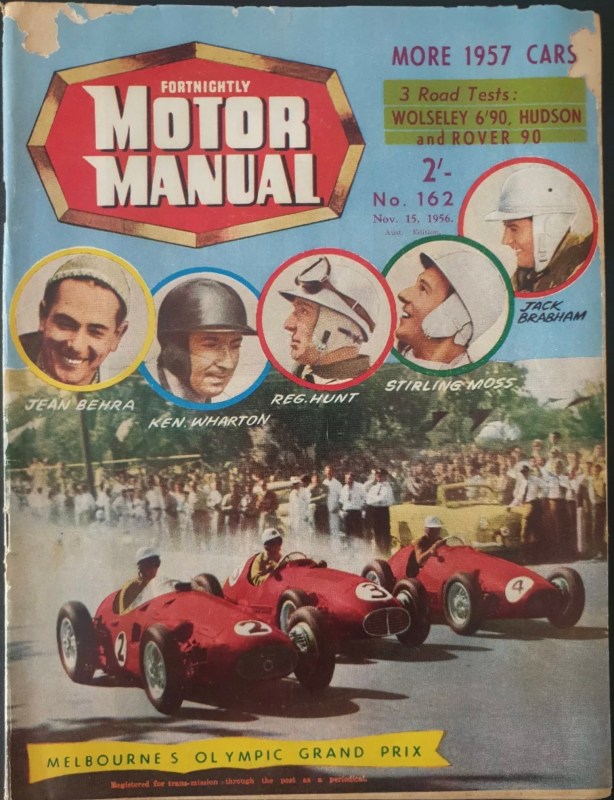

Alberto’s ‘winningest’ 500 chassis, #005 was raced with great success by Australians Tony Gaze and Lex Davison. Davo won the 1957 and 1958 AGPs in it and our first Gold Star, awarded in 1957. Australia’s fascination with all things Ferrari started right there.

After two years of domination Ferrari were confident evolutions of the 500 would suffice for the commencement of the 2.5-litre formula (1954-1960), but the 555/625 Squalo/Super Squalos were dogs no amount of development could fix.

Strapped for cash, Ferrari was in deep trouble until big-spending Gianni Lancia came to his aid. Lancia’s profligate expenditure on some of the most stunning sports and racing cars of all time brought the company to its knees in 1955.

While company founder Vincenzo Lancia turned in his grave, Gianni’s mother dealt with the receivers and Enzo Ferrari chest-marked, free of charge, a fleet of superb, new, Vittorio Jano designed Lancia D50s, spares and personnel in a deal brokered by the Italian racing establishment greased with a swag of Fiat cash.

Juan Manuel Fangio duly delivered the Lancia Ferrari goods by winning the 1956 F1 Drivers Championship in a Lancia Ferrari D50 V8.

Mike Hawthorn followed up with the 1958 Drivers’ Championship victory in the superb Dino 246 V6 which begat Scuderia Ferrari’s next change-of-formula success in 1961.

Concerned with rising F1 speeds (there is nothing new in this world my friends) the FIA imposed a 1.5-litre limit from 1961-1965.

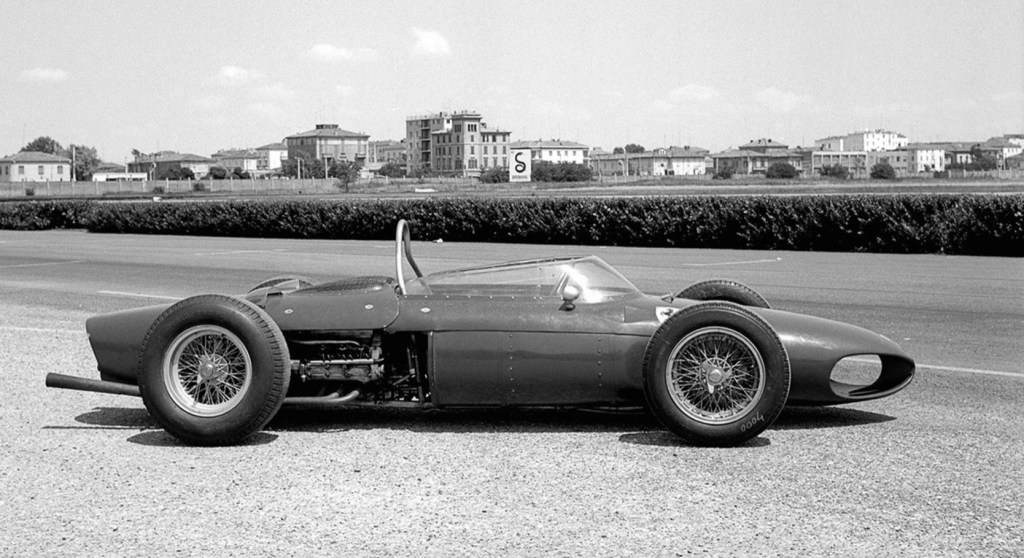

Ferrari raced a 1.5-litre F2 Dino variant from 1958 so were superbly placed to win the 1961 championship despite their first mid-engined 156 racer’s chassis and suspension geometry shortcomings.

The (mainly) British opposition relied on the Coventry Climax 1.5-litre FPF four which gave away heaps of grunt to the Italian V6, only Stirling Moss aboard Rob Walker’s Lotus 18 Climax stood in Ferrari’s way. The championship battle was decided in Phil Hill’s favour after the grisly death of his teammate Count ‘Taffy’ Von Trips and 15 Italian spectators at Monza.

By 1964 Ferrari – never quick to adopt new technology back then – had ditched the 156’s Borrani wire wheels, spaceframe chassis and Weber carburettors thanks to Mauro Forghieri, the immensely gifted Modenese engineer behind much of Ferrari’s competition success for the next couple of decades. John Surtees won the ’64 F1 Drivers and Constructors Championships in a Ferrari 158 V8.

With ‘The Return to Power’, as the 1966-1986 3-litre F1 was billed (3-litres unsupercharged, 1.5-litres supercharged) – sportscars were making a mockery of the pace of 1.5-litre F1 cars – Ferrari and Surtees had a mortgage on the 1966 championships until they shot themselves in the foot.

Coventry Climax, the Cosworth Engineering of the day, withdrew from racing at the end of 1965 leaving their customers scratching around for alternative engines.

Ferrari were again in the box-seat in ’66 as their 312 V12 engined racer was ready nice and early. It was an assemblage of new chassis and an engine and gearbox plucked from the Maranello sportscar parts bins. With a championship seemingly in-the-bag, Modenese-Machiavellian-Machinations led to Surtees spitting the dummy over incompetent team management and walked out.

It was the happiest of days for Jack Brabham, his increasingly quick and reliable Brabham BT19 Repco V8 comfortably saw off Lorenzo Bandini and Mike Parkes who weren’t as quick or consistent as Big John.

Scuderia Ferrari were then in the relative GP wilderness until 1970 just after Fiat acquired Ferrari, but leaving Enzo to run the race division until his demise.

Fiat’s cash was soon converted into 512S sportscars and the most successful V12 ever built. Ferrari’s Tipo 015 180-degree 3-litre masterpiece won 37 GPs from 1970-1980 in the hands of Jacky Ickx, Clay Regazzoni, Mario Andretti, Niki Lauda, Carlos Reutemann, Jody Scheckter and Gilles Villeneuve. Not to forget Constructors’ titles for Ferrari in 1975-1977 and 1979, and Drivers’ championships for Lauda (1975,1977) and Scheckter (1979).

Oops, getting a bit off-topic.

The next F1 step-change wasn’t FIA mandated, but was rather as a consequence of Peter Wright and Colin Chapman’s revolutionary 1977/78 Lotus 78/79 ground effects machines which rendered the rest of the grid obsolete.

Forghieri stunned the F1 world when Ferrari adapted their wide, squat 525bhp 3-litre twelve to a championship winning ground effects car despite the constraints the engine’s width bestowed upon aerodynamicists intent on squeezing the largest possible side-pods/tunnels between the engine/chassis and car’s outer dimensions. Scheckter and Canadian balls-to-the-wall firebrand Villeneuve took three GPs apiece to win titles for Scheckter and Ferrari.

Renault led the technology path forward with its 1.5-litre turbo-charged V6 engines from 1977 but it was Ferrari who won the first Manufacturers Championships so equipped in 1982-83.

The Harvey Postlethwaite designed 560-680bhp 1.5-litre turbo V6 126C2 won three Grands Prix in an awful 1982 for Ferrari. Practice crashes at Zolder and Hockenheim killed Villeneuve and ended Didier Pironi’s career. Keke Rosberg won the drivers title aboard a Williams FW08 Ford in a year when six teams won Grands Prix.

Despite a change to a 3.5-litre/1.5-litres four-bar of boost formula in 1987-88 Ferrari stuck with its turbo-cars. The F1/87 and F1/87/88C designed by Gustav Brunner delivered fourth and second in the Constructors Championships, the victorious cars were the Williams FW11B Honda and McLaren MP4/4 Honda.

Enzo Ferrari died in August 1988, not that the company’s Machiavellian culture and quixotic decision making was at an end…

Rock star ex-McLaren designer John Barnard joined Ferrari in 1987. The first fully-Barnard-car was the seductive 640 built for the first year of the stunning, technically fascinating 1989-1994 3.5-litre formula.

This 660bhp V12 machine, fitted with the first electro-hydraulic, seven-speed paddle-shift, semi-automatic gearbox won three races (Nigel Mansell two, Gerhard Berger, one) and finished third in the constructor’s championship.

Innovative as ever, Barnard’s car wasn’t reliable nor quite powerful enough to beat the Alain Prost (champion) and Ayrton Senna driven McLaren MP4/5B Hondas. Despite six wins aboard the evolved 641 (five for Prost, one to Mansell) in 1990 the car still fell short of McLaren Honda, Senna’s six wins secured drivers and manufacturers titles for the British outfit.

F1’s all-time technology high-water marks are generally regarded as the Williams’ FM14B and FW15C Renault V10s raced by Nigel Mansell and Alain Prost to Drivers and Manufacturers championships in 1992-93. They bristled with innovation deploying active suspension, a semi-automatic gearbox, traction control, anti-lock brakes, fly-by-wire controls and more.

As 1994 dawned Ferrari had been relative also-rans for too long, persevering with V12s long after Renault and Honda V10s had shown the way forward. This period of great diversity – in 1994 Renault, Yamaha, Peugeot, Mugen Honda, Hart, Mercedes Benz and Ilmor Engineering supplied V10s, while Cosworth Engineering provided several different Ford V8s, not to forget Ferrari’s Tipo 043 V12 – ended abruptly at Imola during the horrific May weekend when Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger lost their lives in separate, very public accidents.

In response, FIA chief Max Mosley mandated a series of immediate safety changes and introduced a 3-litre capacity limit from 1995-2004.

Ferrari’s 412T2 V12s finished a distant third in the 1995 Constructors Championship behind Renault powered Benetton and Williams. Much better was the three wins secured by recent signing, Michael Schumacher aboard the V10 (hooray finally!) engined F310, and four with the 310B in 1996-97. Ferrari’s Head of Aerodynamics in this period was Aussie, Willem Toet (1995-1999).

Ferrari’s Holy Racing Trinity were anointed when Jean Todt, Ross Brawn and Michael Schumacher (not to forget Chief Designer Rory Byrne) came together as CEO, Technical Director and Lead Driver; six Constructors World Championships flowed from 1999 to 2004.

Renault and Fernando Alonso took top honours with the R25 in 2005, but Ferrari were handily placed for the first year of the 2.4-litre V8 formula in a further emasculation of the technical differences between marques in 2006. Mind you, the primeval scream of these things at 20,000rpm or so is something we can only dream of today.

Ferrari’s 248 F1 used an updated F2005 chassis fitted with the new Tipo 056 715-785bhp V8. It came home like a train in the back end of the season, winning seven of the last nine races, but fell short of the Renault R26 in both the Constructors and Drivers titles.

Alonso beat Schumacher 134 points to 121, and Renault 206 points to Ferrari’s 201 but the 248 F1 won 9 races (Schumacher seven, Felipe Massa two) to Renault’s 8 (Alonso seven, Giancarlo Fisichella one), so let’s say it was a line-ball thing…and Kimi Raikkonen brought home the bacon for himself and Ferrari with the new F2007 in 2007.

In more recent times the whispering 1.6-litre single turbo V6 formula, incorporating an energy recovery system, was introduced in 2014.

Ferrari fielded two world champions for the first time since 1954 (Giuseppe Farina and Alberto Ascari) when Alonso and Raikkonen took the grid in new F14T’s, but that dazzling combo could do no better than two podiums in a season dominated by Lewis Hamilton’s and Nico Rosberg’s Mercedes F1 W05 Hybrids.

Ferrari’s season was a shocker, it was the first time since 1993’s F93A that the Scuderia had not bagged at least one GP win.

So, what does history tell us about Ferrari’s prospects in this 2022 formula change year? Given our simple analysis, at the start of the season Ferrari had a 36% chance of bagging both titles, but with two out of four wins early on for Charles Leclerc they must be at least an even money chance now.

I’m not so sure I’d put my house on them, but I’d happily throw yours on lucky red!

Credits…

formula1news.co.uk, goodwood.com, ferrari.com, LAT, MotorSport

Finito…