The way it was.

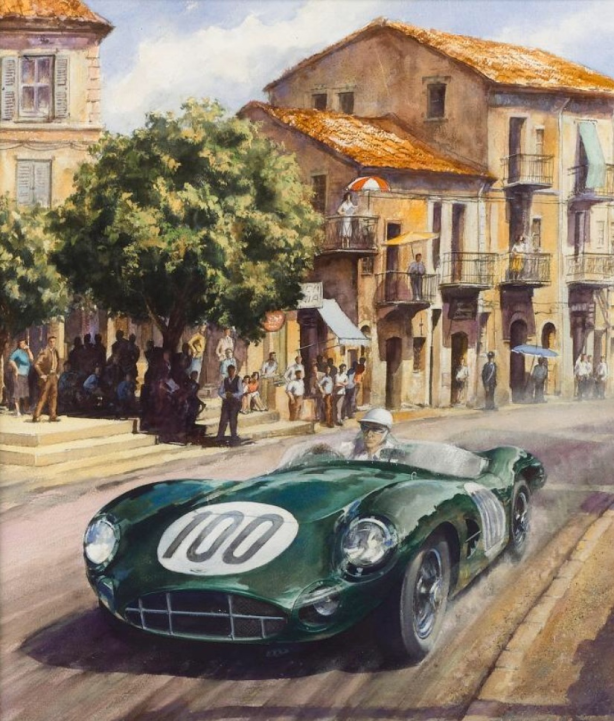

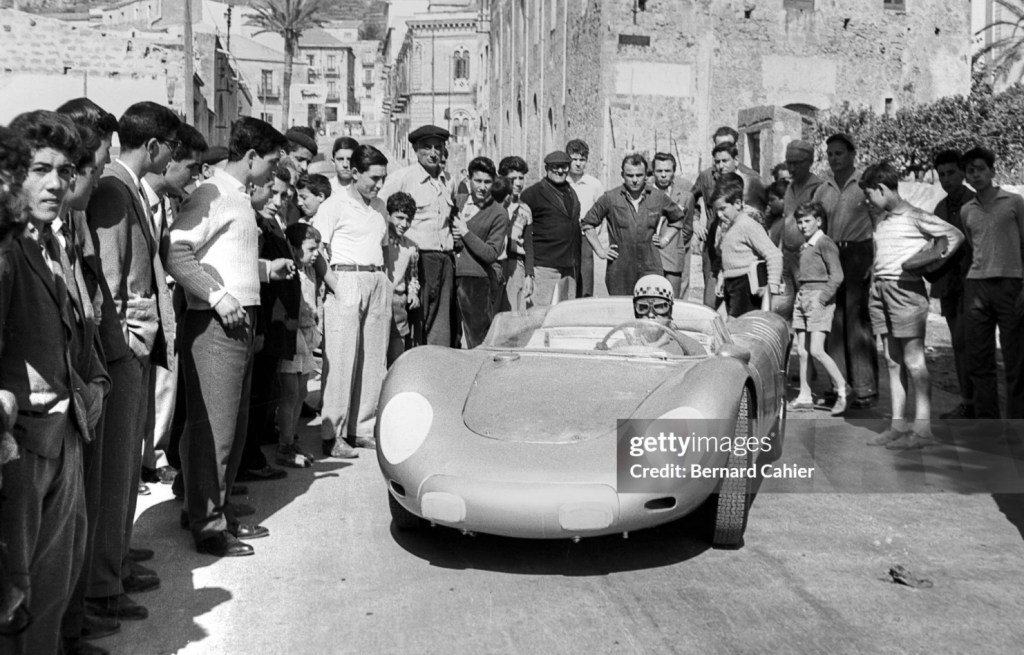

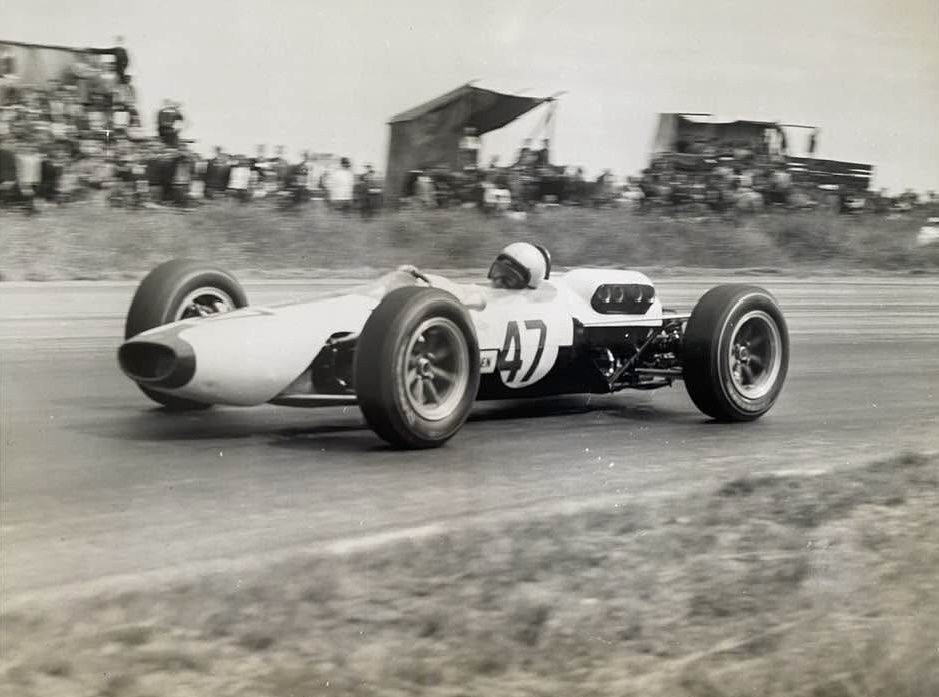

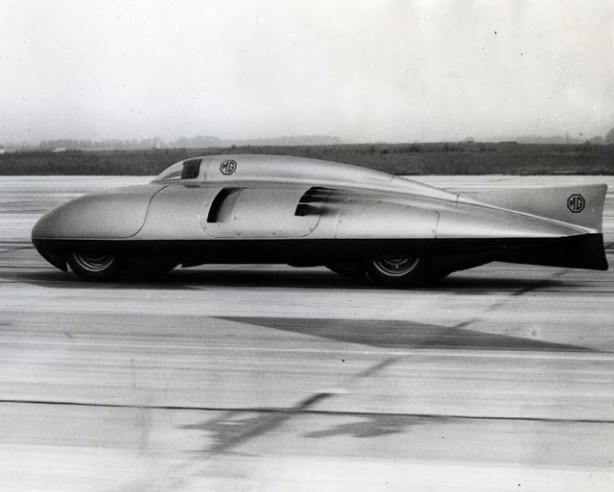

Pat Hoare’s Ferrari 256 V12 ‘0007’ as despatched by Scuderia Ferrari in early 1961…

It was just another chassis after all, Enzo Ferrari was not to know that Dino 256 ‘0007’ would be, so far at least, the last front engined championship Grand Prix winner, so it seemed perfectly logical to refashion it for a client and despatch it off to the colonies. Not that he was an historian or sentimentalist anyway, the next win was far more important than the last.

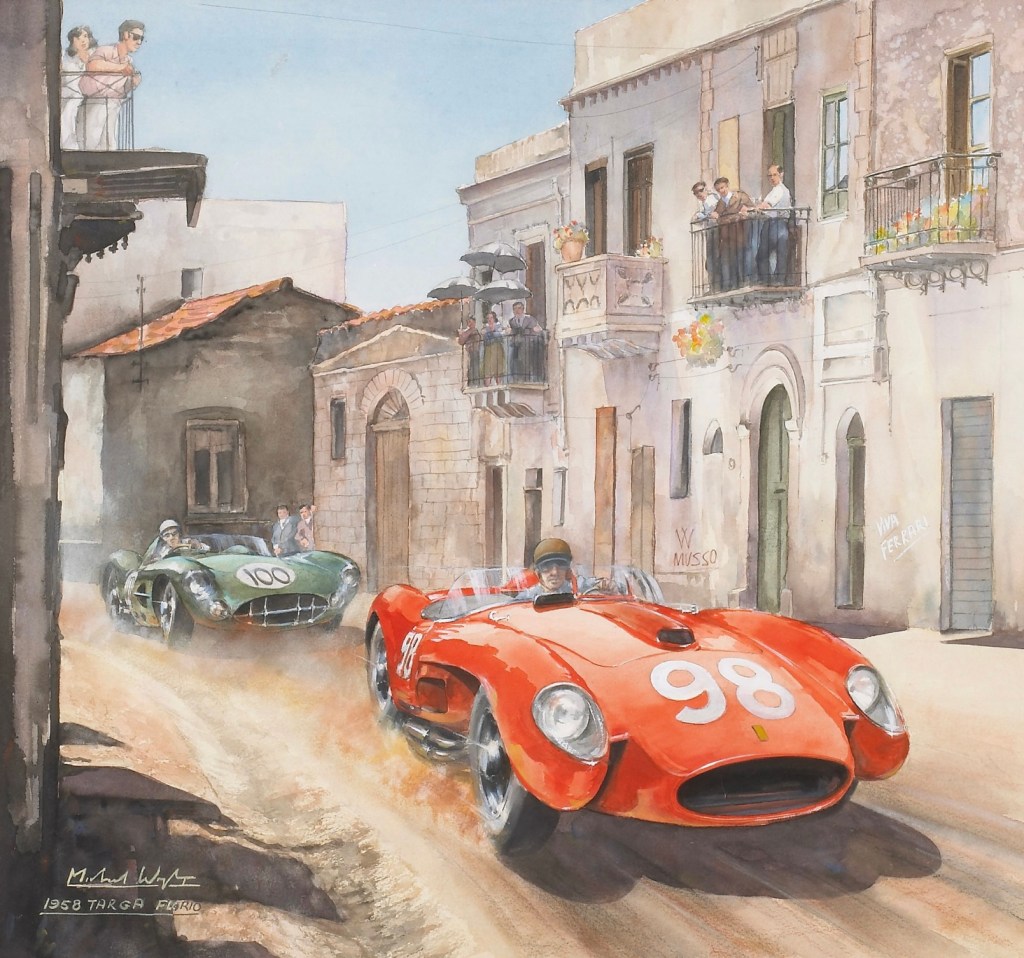

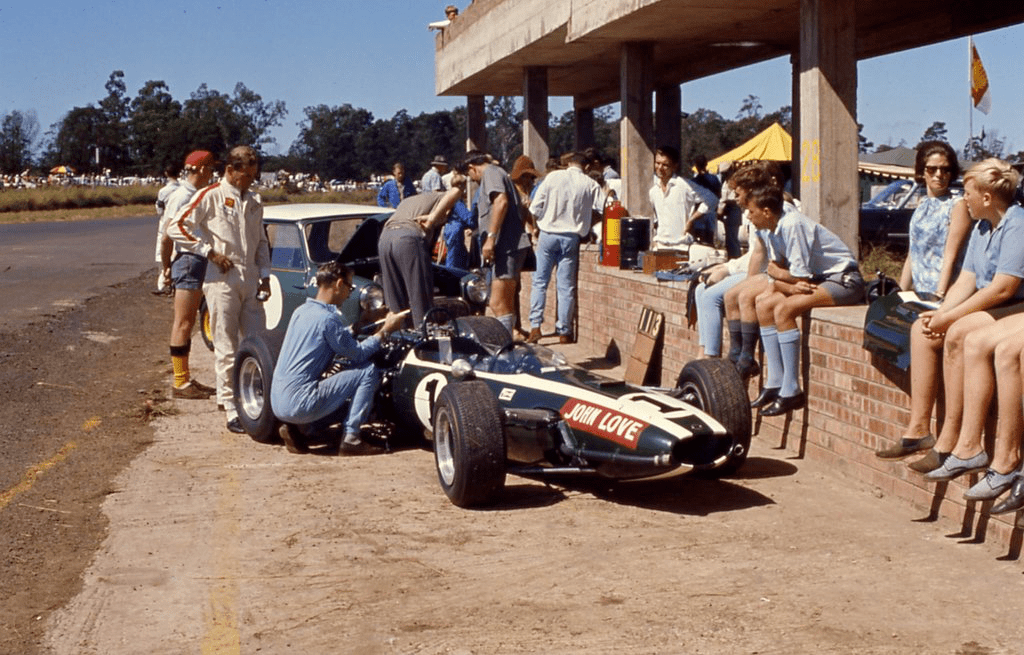

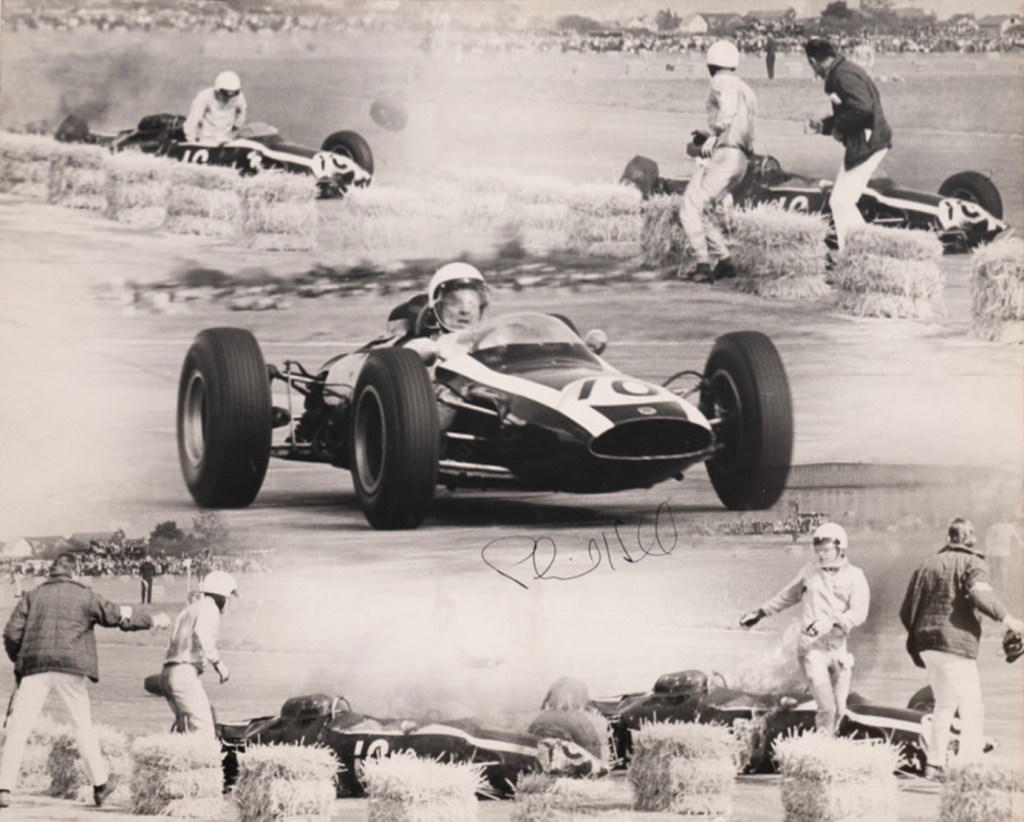

This story of this car is pretty well known and goes something like this- Phil Hill’s 1960 Italian GP winning Ferrari Dino 256 chassis ‘0007’ was the very last front-engined GP winning machine- a win made possible due to the sneaky Italian race organisers running their GP on the high-speed banked Monza circuit to give Ferrari the best possible chance of winning the race- by that time their superb V6 front engined machines, even in the very latest 1960 spec, were dinosaurs surrounded as they were by mid-engined, nimble, light and ‘chuckable’, if less powerful cars.

Hill and Brabham- 256 Dino ‘0007’ and Cooper Climax T53 and during Phil and Jack’s titanic dice at Reims in 1960 (Motorsport)

Phil on the Monza banking, September 1960, 256/60 Dino ‘0007’

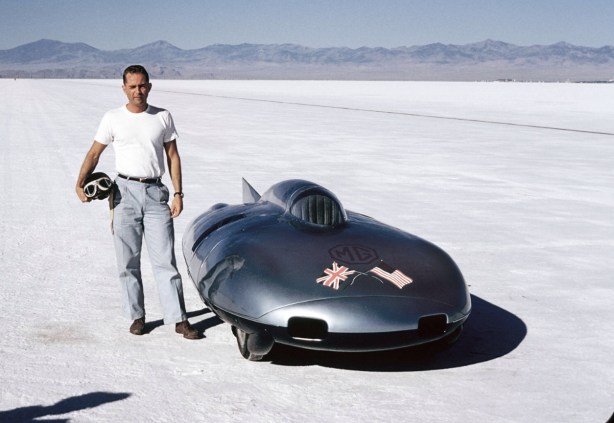

Pat Hoare bought the car a couple of months after that win with the ‘dinky’ 2474cc V6 replaced by a more torquey and powerful 3 litre V12 Testa Rossa sportscar engine.

After a couple of successful seasons Hoare wanted to replace the car with a 1961/2 mid-engined ‘Sharknose’ into which he planned to pop a bigger engine than the 1.5 litre V6 original- but he had to sell his other car first. Enzo didn’t help him by torching each and every 156 mind you. Despite attempts to sell the 256 V12 internationally there were no takers- it was just an uncompetitive front-engined racing car after all.

Waimate 50 11 February 1961, Pat was first from Angus Hyslop’s Cooper T45 Climax and Tony Shelly’s similar car (N Matheson Beaumont)

Pat Hoare, Ferrari Bob Eade, in the dark coloured ex-Moss/Jensen/Mansel Maserati 250F Dunedin February 1962. Jim Palmer, Lotus 20 Ford won from Hoare and Tony Shelly, Cooper T45 Climax (CAN)

Unable to sell it, Hoare had this ‘GTO-esque’- ok, there is a generosity of spirit in this description, body made for the machine turning it into a road car of prodigious performance and striking looks- the artisans involved were Ernie Ransley, Hoare’s long-time race mechanic, Hec Green who did the body form-work and G.B McWhinnie & Co’s Reg Hodder who byilt the body in sixteen guage aluminium over nine weeks and painted it. George Lee did the upholstery.

Sold to Hamilton school teacher Logan Fow in 1967, he ran it as a roadie for a number of years until British racer/collector Neil Corner did a deal to buy the car sans ‘GTO’ body but with the open-wheeler panels which had been carefully retained, the Ferrari was converted back to its V6 race specification and still competes in Europe.

Low took a new Ferrari road car, variously said to be a Dino 308 or Boxer in exchange, running around Europe in it on a holiday for a while but ran foul of the NZ Government import rules when he came home and had the car seized from him by customs when he failed to stump up the taxes the fiscal-fiends demanded- a sub-optimal result to say the least.

Allan Dick reported that the Coupe body could be purchased in Christchurch only a couple of years ago.

Hoare aboard the 256 Coupe at Wigram circa 1964 (Graham Guy)

The guts of this piece is a story and photographs posted on Facebook by Eric Stevens on the ‘South Island Motorsports’ page of his involvement with Pat Hoare’s car, in particular its arrival in New Zealand just prior to the 1961 New Zealand Grand Prix at Ardmore that January.

It is a remarkable insiders account and too good to lose in the bowels of Facebook, I am indebted to Stephen Dalton for spotting it. Eric’s wonderful work reads as follows.

The Arrival of Pat Hoare’s second Ferrari…

‘…that Pat Hoare could buy the car was not a foregone conclusion. Ferrari sent him off for test laps on the Modena circuit in one of the obsolete Lancia D50 F1 cars. Probably to everyone’s surprise., Pat ended up, reputedly, within about 2 seconds of Ascari’s lap record for the circuit.’ (in that car for the circuit)

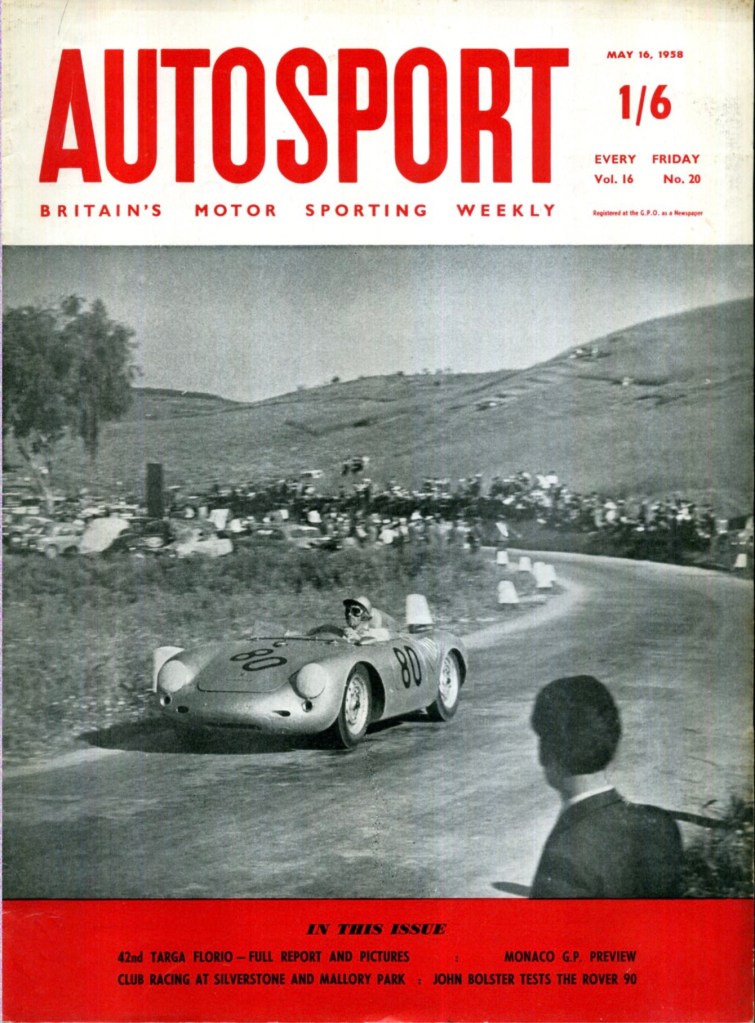

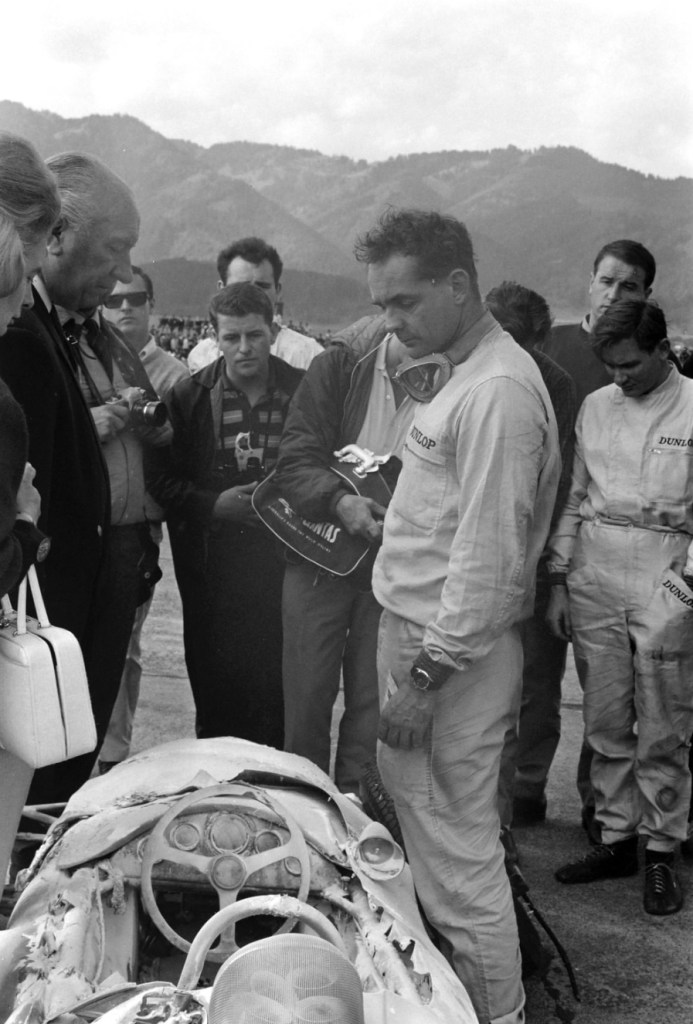

‘The Ferrari was schedued to be shipped to New Zealand in late 1960 in time to be run in the 1961 Ardmore NZ GP, in the event the whole program seemed to be running dangerously late. The first delay was getting the car built at the factory. Then, instead of just a few test laps around Modena, the car became embroiled in a full scale tyre testing program for Dunlop on the high speed circuit at Monza.’

‘It can be seen from the state of the tyres (on the trailer below) that the car had obviously seen some serious mileage. Also there were some serious scrape marks on the bottom of the gearbox where it had been contacting the banking. Nobody in Auckland knew what speeds had been involved but upon delivery the car was fitted with the highest gearing which gave a theoretical maximum speed of 198mph.’

(E Stevens)

(E Stevens)

‘The car was driven straight from Monza to the ship. I was later told by Ernie Ransley that the car was filled with fuel and the delivery driver was told he had approximately an hour to deliver the car to the ship which was somewhat more than 120 miles away.’

‘Then the ship arrived later in Auckland than expected and although Pat had arranged to get the car off as soon as possible there was great panic when at first the car could not be found. Not only was the Hoare team frantically searching the ship, so too was the local Dunlop rep- eventually the car was found behind a wall of crates of spirits in the deck-liquor locker.’

‘Then there was the problem of the paperwork. At first all that could be found was an ordinary luggage label tied to the steering wheel in the opening photograph, this was addressed to; PM Hoare, 440 Papanui Road, Christchurch NZ, Wellington ,NZ. No other papers could be found but an envelope of documents was later found stuffed in a corner. The car had obviously arrived very late.’

(E Stevens)

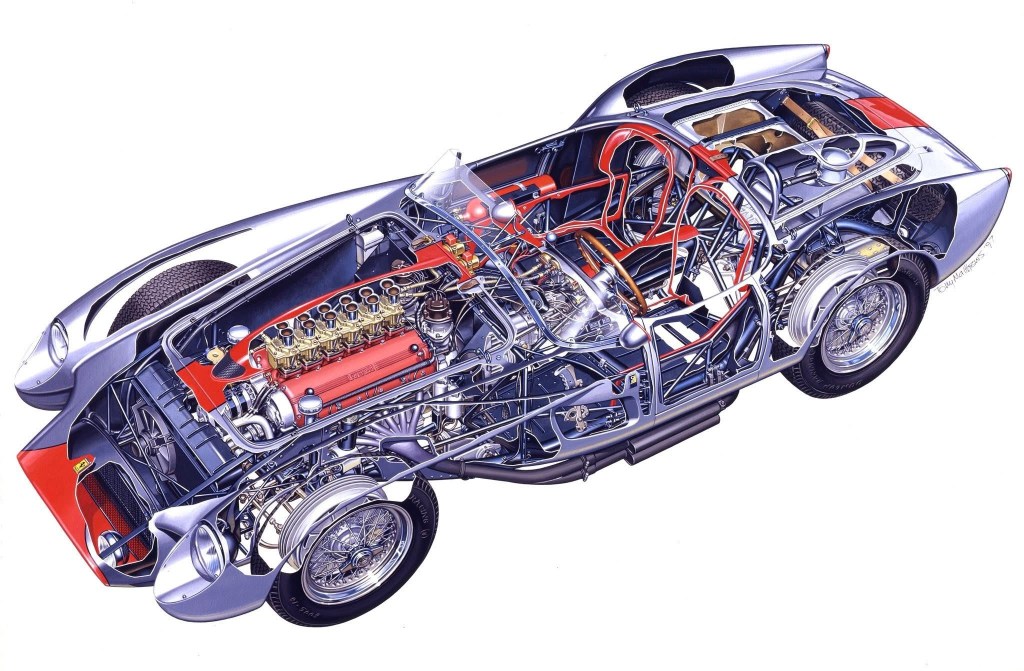

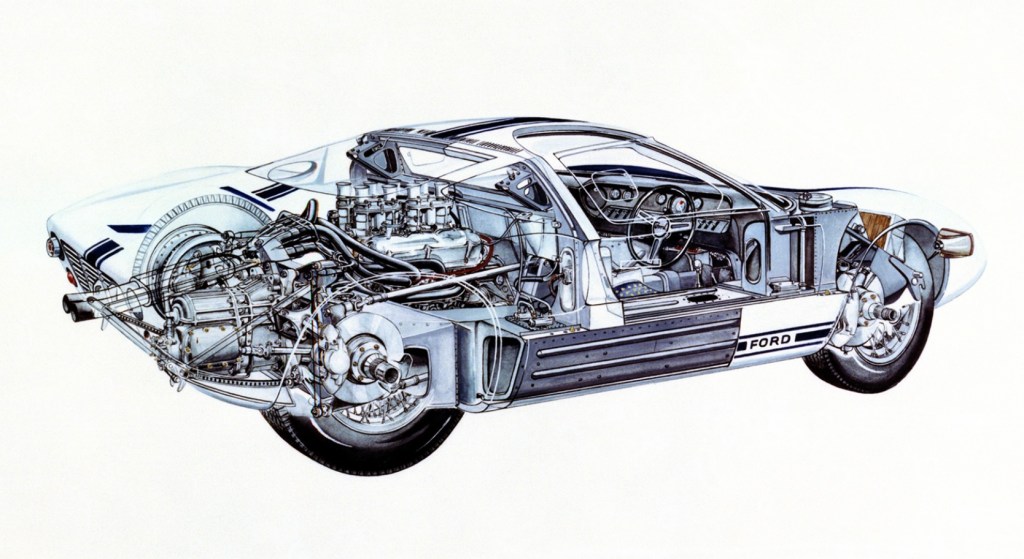

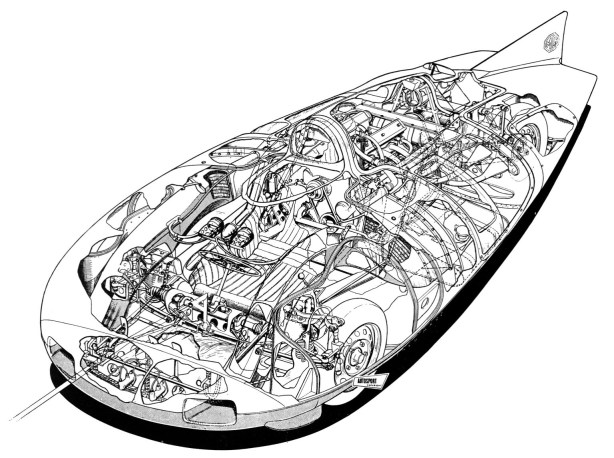

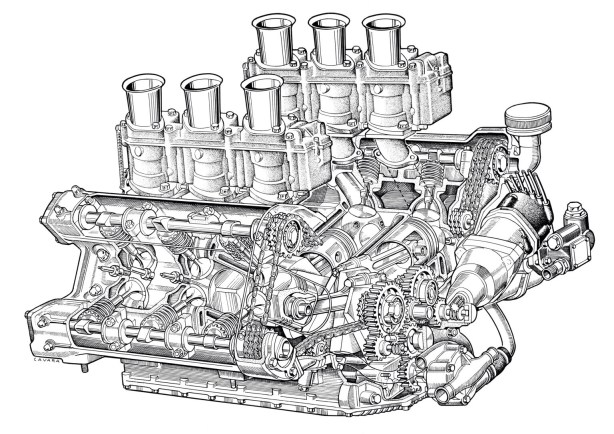

The 3 litre variant of the Colombo V12 used in the Testa Rossas was based on that used in the 250 GT road cars, the primary modifications to the basic SOHC, two valve design were the adoption of six instead of three Weber 38 DCN carbs, the use of coil rather than ‘hairpin’ or torsion springs- this released the space to adopt 24 head studs. One plug per cylinder was used, its position was changed, located outside the engine Vee between the exhaust ports, better combustion was the result. Conrods were machined from steel billet- the Tipo 128 gave 300bhp, doubtless a late one like this gave a bit more. These Colombo V12’s provided the bulk of Ferrari road engines well into the sixties and provided Ferrari their last Le Mans win- Jochen Rindt and Masten Gregory won the 1965 classic in a NART 250LM powered by a 3.3 litre Colombo V12

(E Stevens)

‘The day after collecting the car, and after fitting of new tyres, we took it out to the local supermarket car park for its first run in NZ. Pat climbed in and we all pushed. The car started easily but was running on only 11 cylinders and there was conspicuous blow-back from one carburettor- the immediate diagnosis was a stuck inlet valve.’

‘There was no time to get new valves and guides from the factory but Ernie Ransley was able to locate a suitable valve originally intended for a 250F Maserati and a valve guide blank which, while not made of aluminium bronze, could be machined to suit. Over the next day or so the engine was torn down, the new valve and guide fitted, and all the remaining guides were lightly honed to ensure there would be no repeat failure.’

‘The rest is history.’

‘I musn’t forget the tyres. They were obviously worn and would have to be replaced. They had a slighly different pattern from the usual Dunlop R5 and Ernie Ransley had a closer look at them to see what they were. When the Dunlop rep arrived next Ernie asked him “What is an R9?”. “Oh, just something the factory is playing with” was the answer. In fact they were a very early set of experimental rain tyres, the existence of which was not generally known at the time. There had been no time to get them off the car before it left Monza for the ship. No wonder the Dunlop rep was keen to help us find the car on the ship and get the new tyres on the car as soon as possible.’

It is long- i wonder how much longer in the wheelbase than the 2320mm it started as ? (E Stevens)

Good look at the IRS wishbone rear suspension, rear tank oil, inner one fuel with the rest of that carried either side of the driver (E Stevens)

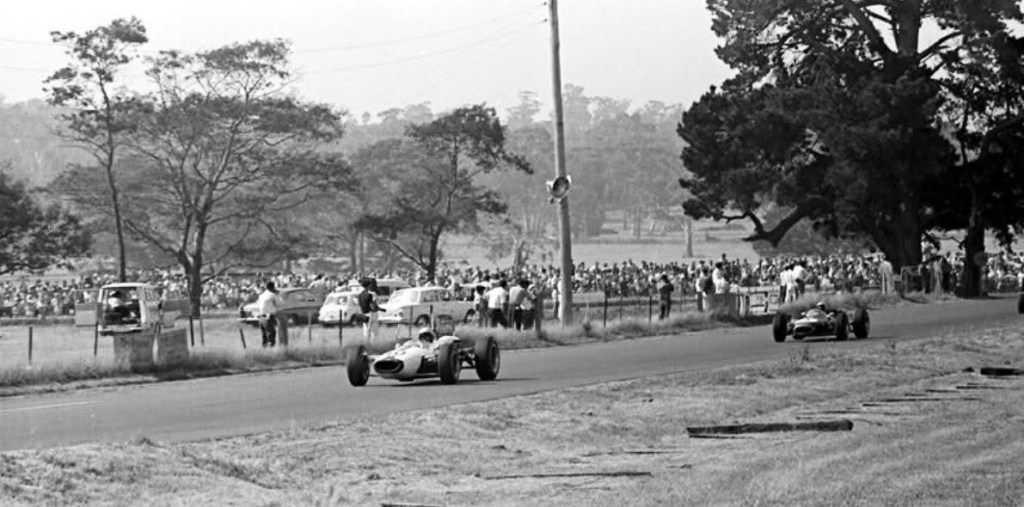

The repairs effected by the team held together at Ardmore on 7 January 1961.

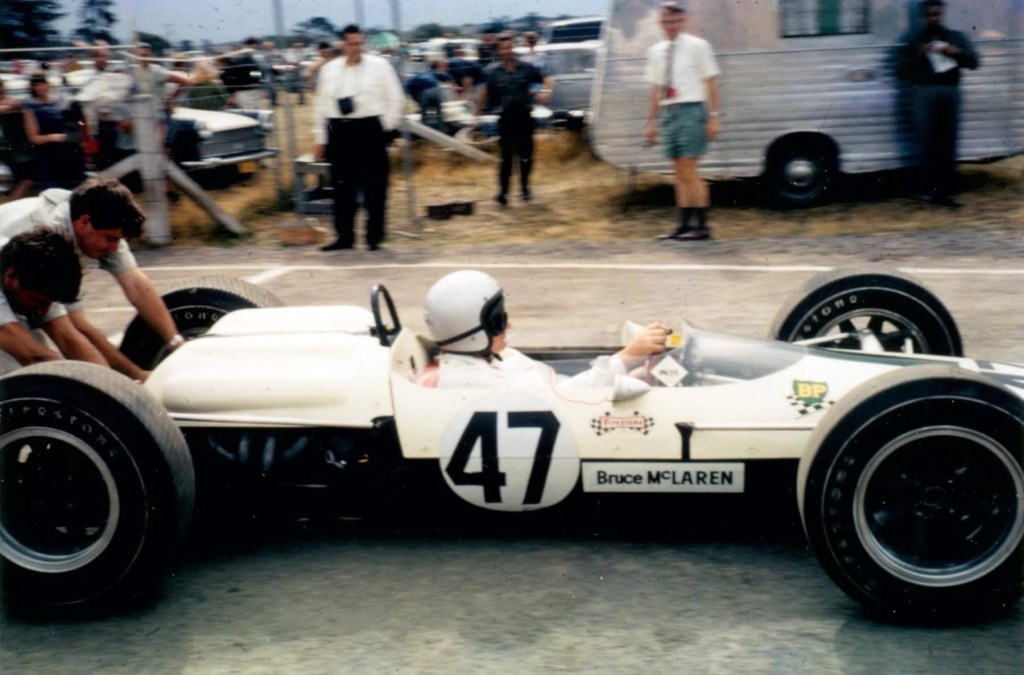

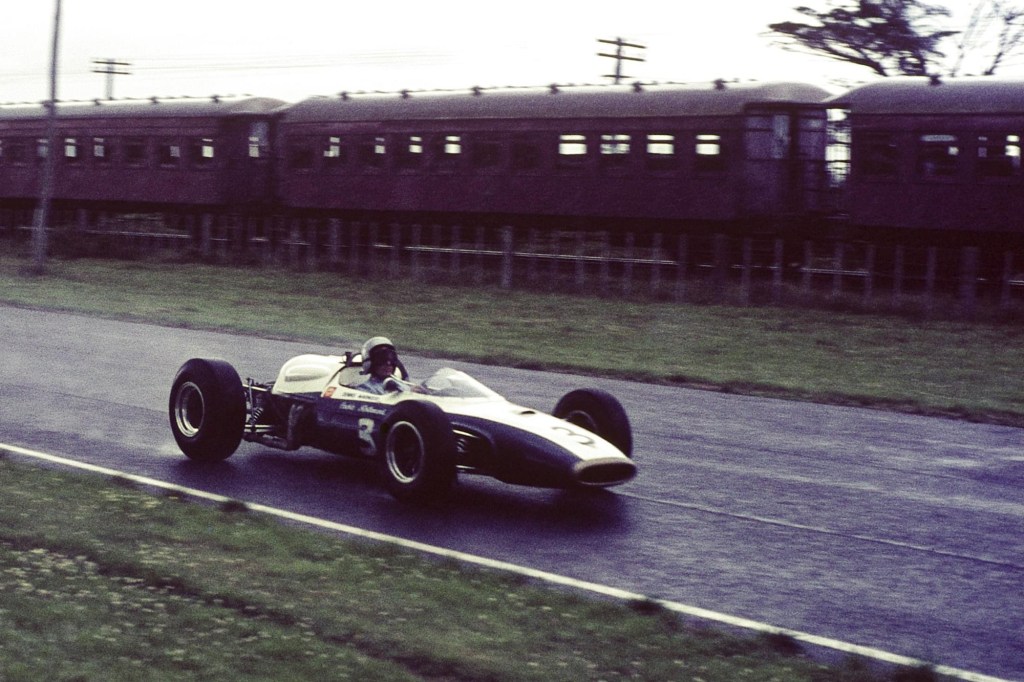

Pat qualified fourteenth based on his heat time and finished seventh- the first front engined car home, the race was won by Brabham’s Cooper T53 Climax from McLaren’s similar car and Graham Hill’s works BRM P48.

Jo Bonnier won at Levin on 14 January- Pat didn’t contest that race but followed up with a DNF from Q14 at the Wigram RNZAF base, Brabham’s T53 won. The internationals gave the Dunedin Oval Circuit a miss, there he was second to Hulme’s Cooper T51 from the back of the grid. Off south to Teretonga he was Q3 and fourth behind Bonnier, Cooper T51 and Salvadori’s Lotus 18 Climax.

After the Internationals split back to Europe he won the Waimate 50 from pole with Angus Hyslop and Tony Shelly behind him in 2 litre FPF powered Cooper T45’s and in November the Renwick 50 outside Marlborough.

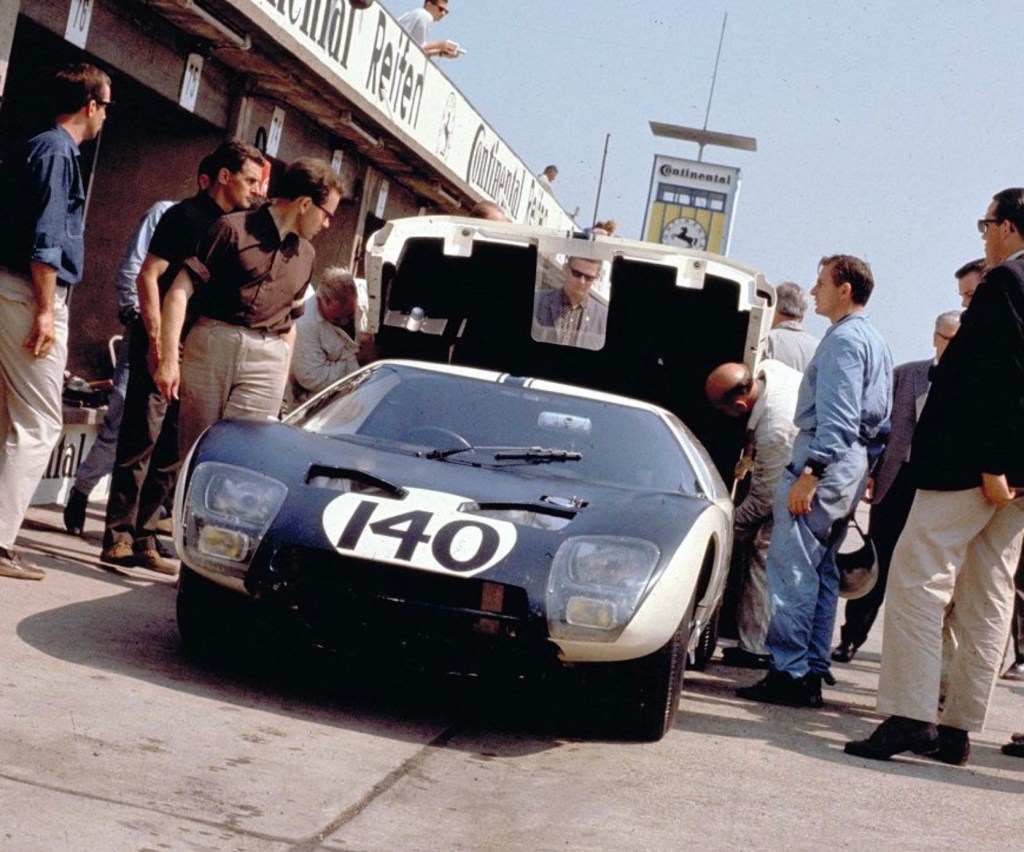

1961 NZ GP Ardmore scene- all the fun of the fair. Ferrari 256 being tended by L>R Doug Herridge, Walter ?, Ernie Ramsley, Don Ramsley and Pat. #3 McLaren Cooper T53, David McKay’s Stan Jones owned Maserati 250F- the green front engined car to the left of the Maser is Bib Stillwell’s Aston Martin DBR4-300 (E Stevens)

Hoare, Ardmore 1962 (E Stevens)

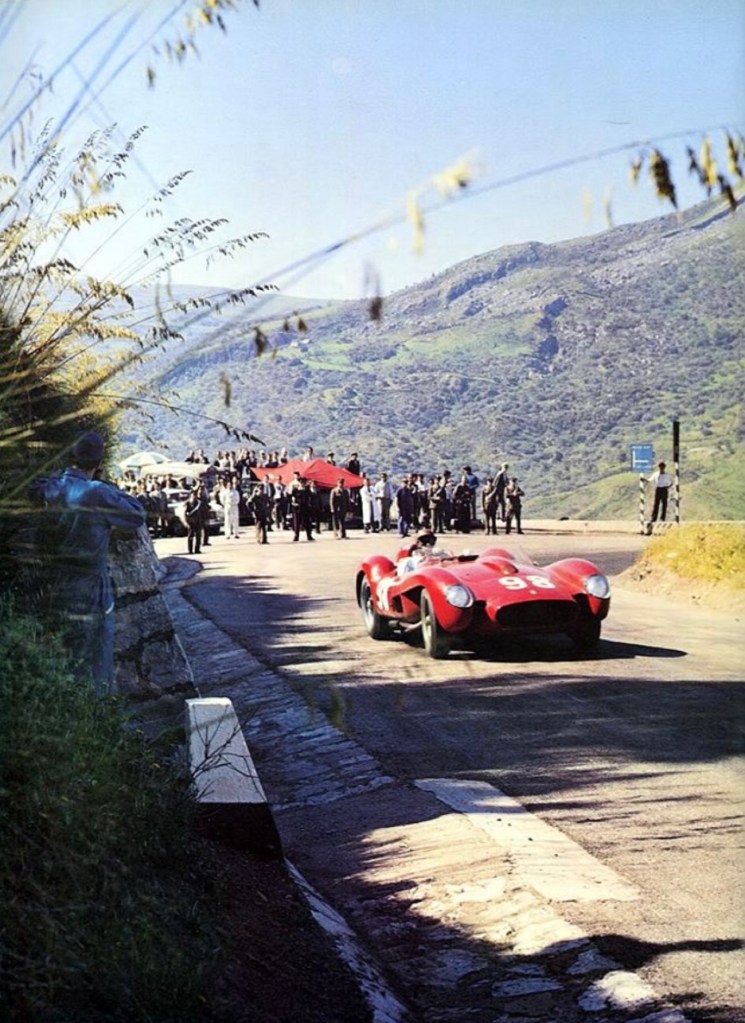

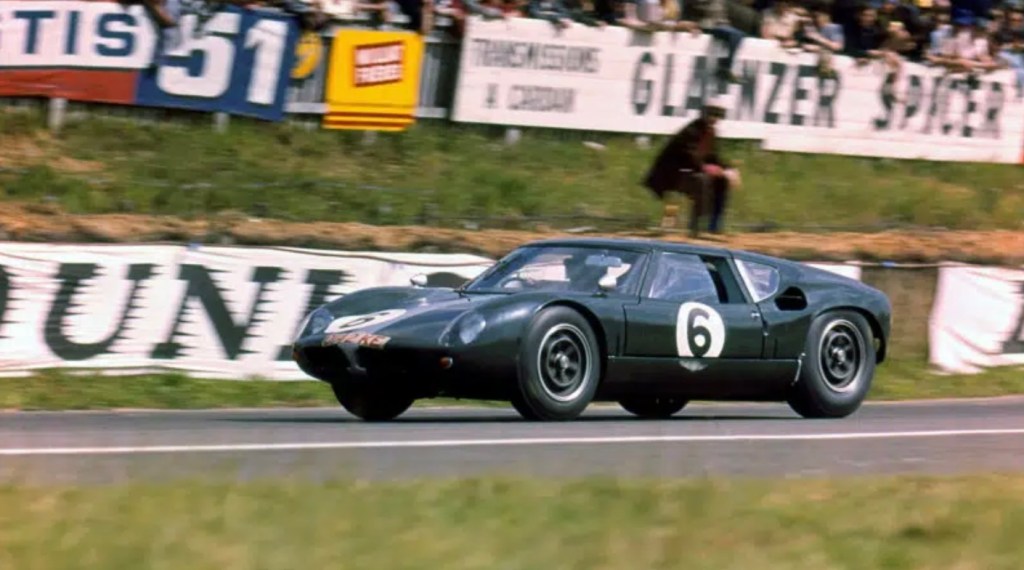

Pat during the Sandown International weekend in March 1962 (autopics.com)

Into January 1962 Stirling Moss, always a very happy and popular visitor to New Zealand and Australia won his last NZ GP at Ardmore in a soaking wet race aboard Rob Walker’s Lotus 21 Climax from four Cooper T53’s of John Surtees, Bruce McLaren, Roy Salvadori and Lorenzo Bandini- the latter’s Centro Sud machine Maserati powered, the other three by the 2.5 litre Coventry Climax FPF, and then Pat’s Ferrari. The car was no doubt feeling a bit long in the tooth by this stage despite only having done eight meetings in its race life to this point.

Pat didn’t contest Levin on 13 January, Brabham’s Cooper T55 Climax took that, but the Sunday after was tenth at Wigram from Q12 with Moss triumphing over Brabham and Surtees in a Cooper T53.

At Teretonga it was McLaren, Moss and Brabham with Pat seventh albeit the writing was well and truly on the wall with Jim Palmer, the first resident Kiwi home in a Cosworth Ford 1.5 pushrod powered Lotus 20.

Having said that Pat turned the tables on Palmer at Dunedin on February 3- this was the horrible race in which Johnny Mansel lost his life in a Cooper T51 Maserati. A week later at Waimate it was Palmer, Hoare and Tony Shelly in a 2 litre FPF powered Cooper T45.

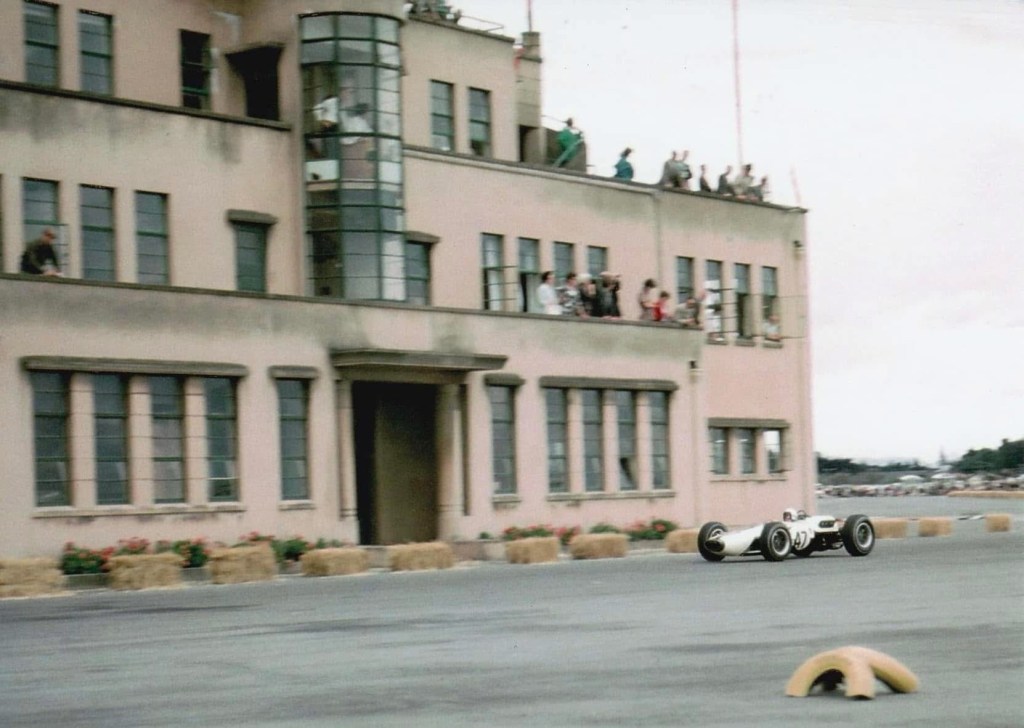

Hoare decided to contest Sandown’s opening meeting on 12 March so the gorgeous machine was shipped from New Zealand to Port Melbourne for this one race- he didn’t contest any of the other Australian Internationals that summer, perhaps the plan was to show it to a broader audience of potential purchasers.

The race was a tough ask- it may have only been eighteen months since the chassis won the Italian GP but the advance of technology in favour of mid-engine machines was complete, as Pat well knew. Jack Brabham won the 60 lap race in his Cooper T55 Climax FPF 2.7 from the similarly engined cars of John Surtees and Bruce McLaren who raced Cooper T53’s- the first front-engined car was Lex Davison’s Aston Martin DBR4/250 3 litre in eighth.

Pat was eighth in his heat- the second won by Moss’ Lotus 21 Climax and started sixteenth on the grid of the feature race, he finished eleventh and excited many spectators with the sight and sound of this glorious, significant machine.

And that was pretty much it sadly…

Hill in ‘0007’ and Brabham’s Cooper T53 Climax ‘Lowline’ went at hammer and tongs for 29 of the 36 laps in one of the last great front-engine vs rear-engine battles- here Jack has jumped wide to allow Phil, frying his tyres and out of control as he tries to stop his car- passage up the Thillois escape road, French GP 1960 (Motorsport)

Ferrari Dino 256/60…

I’ve already written a couple of pieces on these wonderful Ferraris- the ultimate successful expression of the front engined F1 car, here; https://primotipo.com/2017/07/14/composition/ and here; https://primotipo.com/2014/07/21/dan-gurney-monsanto-parklisbonportuguese-gp-1960-ferrari-dino-246-f1/

The history of 256/60 ‘0007’ and its specifications are as follows sourced from Doug Nye’s ‘History of The Grand Prix Car’, a short article i wrote about the car a while back is here; https://primotipo.com/2015/11/09/pat-hoares-ferrari-256-v12-at-the-dunedin-road-race-1961/

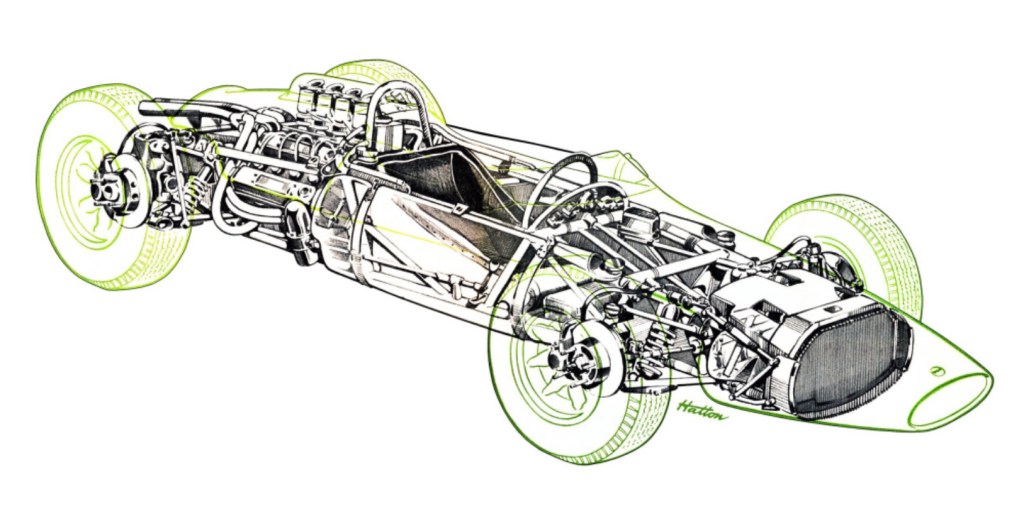

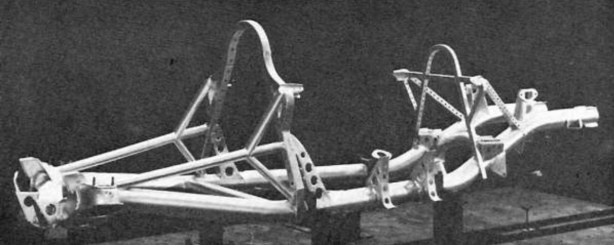

The 1960 Dinos had small tube spaceframe chassis, disc brakes, wishbone and coil spring/dampers front- and rear suspension, de-Dion tubes were gone by then. The V6 engines, tweaked by Carlo Chiti were of 2474cc in capacity, these motors developed a maximum of 290bhp @ 8800rpm but were tuned for greater mid-range torque in 1960 to give 255bhp for the two-cam and 275bhp @ 8500rpm for the four-cammers. Wheelbase of the cars was generally 2320mm, although shorter wheelbase variants were also raced that year, the bodies were by Fantuzzi.

‘0007’ was first raced by Phil Hill at Spa on 19 June-Q3 and fourth, Brabham’s Cooper T53 Climax the winner, he then raced it at Reims, Q2 and DNF gearbox with Jack again up front, Silverstone, Q10 and seventh with Jack’s Cooper up front again and in Italy where Hill won from pole before it was rebuilt into ‘Tasman’ spec. Obviously the machine had few hours on it when acquired by Hoare- it was far from a worn out old warhorse however antiquated its basic design…

Nye records that seven cars were built by the race shop to 1960 246-256/60 specifications- ‘0001’, ‘0003’, ‘0004’, ‘0005’, ‘0006’, ‘0007’ and ‘00011’. ‘0001’, ‘0004’, ‘0006’ and ‘00011’ were discarded and broken up by the team leaving three in existence of which ‘0007’ is the most significant.

The 250 Testa Rossa engine is one the long-lived, classic Gioachino Colombo designs, evolved over the years and designated Tipo 128, the general specifications are an aluminum 60 degree, chain driven single overhead cam per bank, two-valve 3 litre V12- 2953cc with a bore/stroke of 73/58.8mm with 300bhp @ 7000rpm qouted. The engine in Hoare’s car was dry-sumped and fitted with the usual visually arresting under perspex cover, battery of six Weber 38 DCN downdraft carbs.

(E Stevens)

Pat Hoare in his first Ferrari, the bitza 625 four cylinder 3 litre at Clelands Road, Timaru hillclimb date unknown (E Porter)

Enzo Ferrari, Pat Hoare, Colombo and Rita…

Many of you will be aware of the intrigue created down the decades by Pat Hoare’s ability to cajole cars from Enzo Ferrari, when seemingly much better credentialled suitors failed.

I don’t have David Manton’s book ‘Enzo Ferraris Secet War’ but Doug Nye commented upon its contents in a 2013 Motorsport magazine piece.

‘Neither Mr Ferrari himself nor Pat Hoare ever explained publicly their undeniably close links. The best i ever established was that Hoare had been with the New Zealand Army advancing up the leg of Italy in 1943, and was amongst the first units to liberate Modena from the retreating German Army. David Manton has plainly failed in pinning down chapter and verse to unlock the true story, but he does reveal startling possibilities.’

‘When Mr Ferrari wanted a trusted engineer to realise his ambitions of building a new V12 engined marque post-war, he sought out Ing Gioachino Colombo, his former employee at Alfa Romeo. In 1944-5, however, Colombo was tainted by having been such an enthusiastic Fascist under Mussolini’s now toppled regime. With Communist Partisans taking control, Colombo was fired from Alfa and placed under investigation. His very life hung by a thread. He could have been imprisoned or summarily shot.’

‘Manton believes that Hoare- who had met Ferrari as a confirmed motor racing enthusiast from the pre-war years- may have been instrumental in freeing Colombo by influencing the relevant authorities. Certainly Colombo was able to resume work for Ferrari when some of his former Party colleagues remained proscribed, ar had already- like Alfa Romeo boss Ugo Gobbato and carburettor maker Eduardo Weber- been assassinated.’

‘But David Manton presents the possibility that such mediation might have been only a part of a more intimate link. Pat Hoare’s personal photo album from the period includes several shots of an extremely attractive Italian girl identified only as Rita. He was an un-married 27 year old Army officer. She was a ravishing 18, believed to have been born near Modena around 1926 and raised not by her birth parents, but by relatives. Some of Pat Hoare’s old friends in Christchurch, New Zealand- while fiercely protective of his memory- share a belief that the lovely Rita was not only just an early love of his life, but that she was also the illegitimate daughter of Enzo Ferrari…which would explain so much.’

‘Nothing is proven. David Manton’s book frustratingly teases but so- over so many decades- has the intrinsic discretion and privacy of the Italian alpha male. As American-in-Modena Pete Coltrin told me many years ago, Mr Ferrari was sinply a “complex man in a complex country”. He had a hard won reputation as a womaniser, which itself earned the respect, and admiration of many of his Italian peers and employees. But if Mr Manton’s theories hold any water they certainly go a long way towards explaining the Pat Hoare/Enzo Ferrari relationship, which both considered far too private ever to divulge to an enthusiastic public…’ DC Nye concludes.

Every Tom, Dick and Irving…

I look at all the fuss about Hoare’s purchase of his two Ferraris and wonder whether every Tom, Dick and Harry who had the readies and wanted an F1 Fazz could and did buy one in the fifties?

Ok, if you got Enzo on a bad day when Laura was pinging steak-knives around the kitchen at him for dropping his amply proportioned tweeds yet again he may not have been at his most co-operative but if you copped him the morning after he bowled over Juicy Lucia from down the Via you could probably strike a quick deal on any car available.

Putting all puerile attempts at humour to one side it seems to me Ferrari were pretty good at turning excess stock (surplus single-seater racing cars) into working capital (cash), as every good business owner- and it was a very good business, does. Plenty of 375’s, 500’s, 625’s and 555’s changed hands to the punters it seems to me.

Just taking a look at non-championship entries in Europe from 1950 to 1956, the list of cars which ended up in private hands is something like that below- I don’t remotely suggest this is a complete, and some cars will be double-counted as they pass to a subsequent owner(s), but is included to illustrate the point that in the fifties ex-works Ferrari F1 cars being sold was far from a rare event.

Its not as long a list as D Type Jaguar or DB3S Aston owners but a longer list than one might think.

Peter Whitehead- 125, 500/625 and 555 Super Squalo Tony Vandervell- 375, Bobbie Baird- 500 Bill Dobson-125 Chico Landi- 375 Piero Carini- 125 Franco Comotti- 166.

Four 375’s were sold to US owners intended for the 1952 Indy 500

Rudolf Fischer- 500, Jacques Swaters ‘Ecurie Francorchamps’- 500 and 625, Charles de Tornaco ‘Ecurie Belgique’- 500, Louis Rosier ‘Ecurie Rosier’- 375, 500 and 625, Tom Cole- 500, Roger Laurent- 500, Kurt Adolff- 500, Fernand Navarro- 625, Carlo Mancini- 166, Guido Mancini- 500, Tony Gaze- 500/625 Reg Parnell ‘Scuderia Ambrosiana’- 500, 625 and 555 Super Squalo

Ron Roycroft- 375, Jean-Claude Vidille- 500, Alfonso de Portago- 625, Lorenzo Girand- 500, Centro Sud- 500, Jean Lucas- 500, Georgio Scarlatti- 500, Berando Taraschi- 166, Pat Hoare- 500/625 ‘Bitza’ and 256 V12

Don’t get me wrong, I do love the intrigue of the stories about the Enzo and Pat relationship but maybe its as simple as Hoare rocking up to Maranello twice on days when Enzo had had a pleasant interlude with Juicy Lucia on the evening prior rather than on two days when his blood was on the kitchen floor at home.

Etcetera…

(CAN)

Pat Hoare in his first Ferrari ‘bitza’, a 3 litre engined 625 (ex-De Portago, Hawthorn, Gonzales) at Dunedin 1958.

He raced the car for three seasons- 1958 in detuned state the car was not very competitive, in 1959 it kept eating piston rings and in 1960 it was fast and reliable, nearly winning him the Gold Star.

Its said his trip to Maranello in 1960 was to buy a V12 engine to pop into this chassis to replace its problematic four-cyinder engine but Ferrari insisted he bought a whole car.

The specifications of this car vary depending upon source but Hans Tanner and Doug Nye will do me.

The chassis was Tipo 500 (other sources say 500 or 625) fitted with a specially tuned version of a Tipo 625 sportscar engine bored from 2.5 to 2.6 litres. A Super Squalo Tipo 555 5-speed transmission was used to give a lower seating position and a neat body incorporating a Lancia D50 fuel tank completed the car.

When entered in events Pat described it as a Ferrari 625 and listed the capacity as 2996cc.

Pat Hoare portrait from Des Mahoney’s Rothmans book of NZ Motor Racing (S Dalton Collection)

Special thanks…

Eric Stevens and his stunning article and photographs

Photo Credits…

Allan Dick/Classic Auto News, Graham Guy, Mike Feisst, Stephen Dalton Collection, autopics.com

Bibliography…

‘History of The Grand Prix Car’ Doug Nye, grandprix.com, the Late David McKinney on ‘The Roaring Season’, Motorsport February 2013 article ‘The Old Man and the Kiwi’ by Doug Nye

Tailpieces…

(M Feisst)

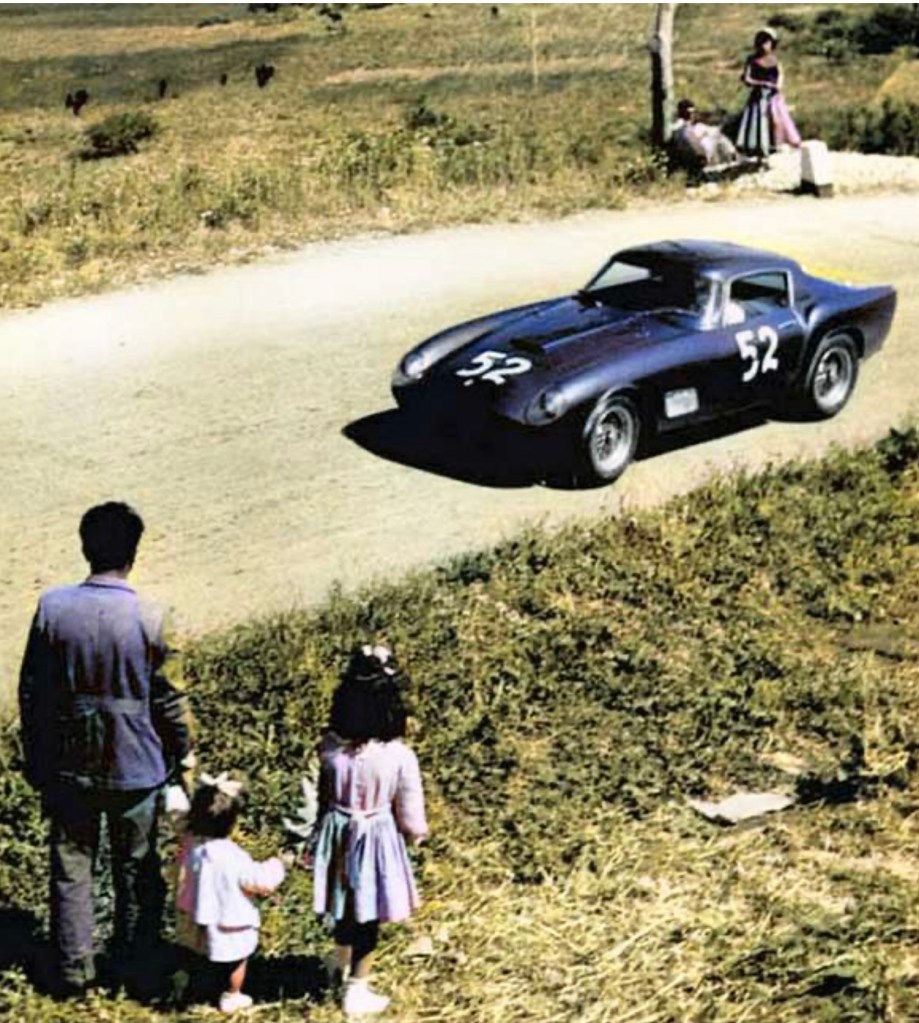

The NZ built ‘Ferrari GTO’ pretty in its own way but not a patch on the genuine article without the extra wheelbase of the ‘real deal’.

(E Stevens)

Bag em up Pat…

Finito…