The second episode covered the design and building of the 1966 ‘RB620’ V8, the engine which would contest and win the World Constructors and Drivers Championships in 1966, this is a summary of that season…

Cutaway drawing of Brabham BT19 # ‘F1-1-65’, JB’s 1966 Championship Winning mount. Produced in 1965 for the stillborn Coventry Climax Flat 16 cylinder 1.5 litre F1 engine and modified by Ron Tauranac to fit the ‘RB620’ engine, which was designed by Phil Irving with Brabham/Tauranacs direct input in terms of ancilliaries etc to fit this chassis. A conventional light, agile, driver friendly and ‘chuckable’ spaceframe chassis Brabham of the period. Front suspension independent by upper and lower wishbones and coil spring/ damper units. Rear by upper top link, inverted lower wishbone, twin radius rods and coil spring/ damper units. Adjustable sway bars front and rear. Hewland HD500, and later DG300 ‘box. Much raced and winning chassis…still in Australia in Repco’s ownership (Motoring News)

The 1966 South African Grand Prix…whilst not that year a Championship round was the first race of the new 3 litre F1 on 1 January.

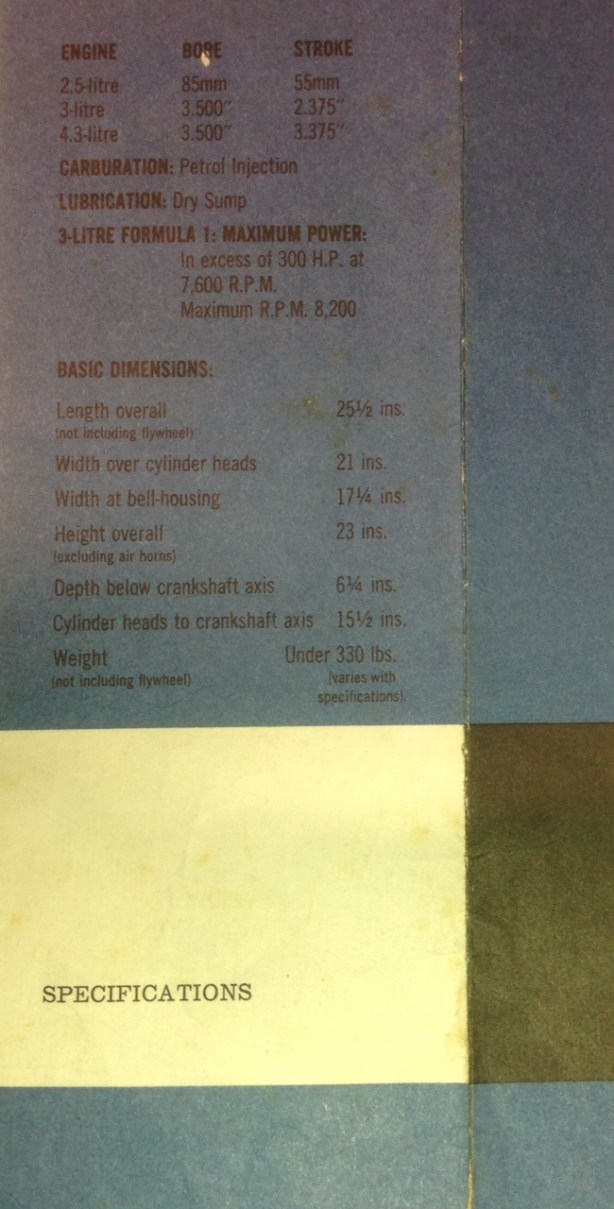

In December 1965 the first 3 Litre RB620 ‘E3’ was assembled and with slightly larger inlet valves, ports and throttle bodies than the ‘2.5’ produced 280bhp @ 7500rpm. After six hours testing it was rebuilt, shipped to the UK and fitted to Jacks ‘BT19’, a chassis built during 1965 for the stillborn Coventry Climax 16 cylinder engine, the rear frame modified to suit ‘RB620’.

Brabham started from pole and lead until the Lucas injection metering unit drive coupling failed. He achieved fastest lap but was the only 3 litre present.

Straight after the race the car was flown to Melbourne and fitted with Repco 2.5 engine ‘E2’ for the Sandown Tasman round on February 27, Repco’s backyard or home event…

Roy Billington prepares BT19 for fitment of the’RB620′ 2.5 Tasman engine in place of the 3 litre used in South Africa on 1 January 1966 (Wolfe/Repco)

Jack Brabham with RB Engines GM Frank Hallam at Sandown 1966. Publicity shot with BT19, long inlet trumpets give the engine away as a ‘Tasman 2.5’. Car sans RH side ‘Lukey Mufflers’ exhaust tailpipe in this shot ‘, sitting across the drivers seat. Rear suspension as described in cutaway drawing above, twin coils, fuel metering unit, HD500 Hewland, battery and ‘expensive’ Tudor oil breather mounted either side of ‘box (Brabhams World Championship Year’ magazine)

During a preliminary race the car set a lap record- the race won by Stewart’s BRM. But in the main race but an oil flow relief valve failed, causing engine damage, Stewart won from Clark Lotus 39 Climax and Graham Hill in the other BRM P261.

Upon dissasembly, it was found a sintered gear in the pressure pump had broken. The engine was then rebuilt for the final Tasman round at Longford Tasmania.

In a close race, with the engine overheating, the car ran short of fuel and was beaten by the two 2 litre BRM P261’s (bored out 1.5 litre F1 cars) of Stewart and Hill, Jackie Stewart easily winning the 1966 Tasman Championship for the Bourne team.

In early January 1966 the engine operation was transferred from Repco’s experimental labs in Richmond to the Maidstone address and factory covered in episode 2 where the operations were ‘productionised’ to build engines for both BRO (Brabham Racing Organisation) and customers.

So far the engine had not covered itself in glory but invaluable testing was being carried out and problems solved.

Meanwhile back in Europe other teams were developing their cars for 1966…

All teams faced the same challenge of a new formula, remember that Coventry Climax, the ‘Cosworth Engineering’ of the day were not building engines forcing the ‘English Garagistes’ as Enzo Ferrari disparagingly described the teams, to find alternatives, as Jack had done with Repco.

Ferrari were expected to do well, as they had done with the introduction of the 1.5 litre Formula in 1961, they had a new chassis and an engine ‘in stock’, which was essentially a 3 litre variant of their 3.3 litre P2 Sports Car engine, the ‘box derived from that car as well. The gorgeous bolide looked the goods but was heavy and not as powerful as was claimed or perhaps Repco’s horses were stallions and the Italian’s geldings!

Hubris or too little focus on F1 in 1966…on paper the Ferrari 312 shoulda’ won in ’66…when Surtees left so did their title hopes, Ferraris’ decline in the season was matched by Brabhams’ lift…

Cooper also used a V12, a 3 litre, updated variant of the 2.5 litre engine Maserati developed at the end of the 250F program in 1957 when it was tested but unraced.

Coopers’ 1966 T81 was an aluminium monocoque chassis carrying a development of Masers’ 10 year old ‘Tipo 10’ 60 degree V12. DOHC, 2 valves per cylinder, Lucas injected, and a claimed 360bhp @ 9500rpm. The cars were heavy, reasonably reliable. Surtees and Rindt extracted all from them (Bernard Cahier)

Dan Gurney had left Brabham and built a superb car designed by ex-Lotus designer Len Terry. The T1G Eagle was to use Coventry Climax 2.7 litre FPF power until Dans’ own Gurney-Weslake V12 was ready. Again, the car was heavy as it was designed for both Grand Prix and Indianapolis Racing where regulation compliance added weight.

Denny Hulme stepped up to fulltime F1 to support Jack in the other Brabham.

The dominant marque of the 1.5 litre formula , Lotus were caught without an engine and contracted with BRM for their complex ‘H16’ and were relying also on a 2 litre variant of the Coventry Climax FWMV 1.5 V8…simultaneously Keith Duckworth was designing and building the Ford funded Cosworth DFV, but its debut was not until the Dutch Grand Prix in 1967.

BRM, having failed to learn the lessons of complexity with their supercharged V16 1.5 litre engine of the early 50’s, and then reaping the benefits of simplicity with the P25/P48/P57, designed the P83 ‘H16’, essentially two of their 1.5 litre V8’s at 180 degrees, one atop the other with the crankshafts geared together. They, like Lotus were also using 2 litre variants of their very fast, compact, light and simple 1965 F1 cars, the P261 whilst developing their ‘H16′ contender.

Honda won the last race of the 1.5 litre formula in Mexico 1965 and were busy on a 3 litre V12 engined car, the RA273 appeared later in the season in Richie Ginthers’ hands.

Richie Ginthers’ powerful but corpulent, make that mobidly obese Honda RA 273 at Monza, the heaviest but most powerful car of 1966…it appeared too late in the season to have an impact but was competitive in Richies’ hands, a winner in ’67 at Monza…(unattributed)

Bruce Mclaren produced his first GP cars, the Mclaren M2A and M2B, technically advanced monocoque chassis of Mallite construction, a composite of balsa wood bonded between sheets of aluminium on each side.

His engine solution was the Ford ‘Indy’ quad cam 4.2 litre V8, reduced to 3 litres, despite a lot of work by Traco, the engine whose dimensions were vast and heavy, developed way too little power, the engine and gearbox weighing not much less than BT19 in total…He also tried an Italian Serenissima engine without success.

Bruce testing M2A Ford at Riverside, California during a Firestone tyre test in early 1966. M2A entirely Mallite, M2B used Mallite inner, and aluminium outer skins. Note the wing mount…wing first tested at Zandvoort 1965. L>R: Bruce McLaren, Gary Knutson, Howden Ganley and Wally Willmott (Tyler Alexander)

So, at the seasons outset Brabham were in a pretty good position with a thoroughly tested engine, but light on power and on weight in relation to Ferrari who looked handily placed…

Variety is the spice- 1966 MotorSport magazine visual of the different F1 engine solutions pursued by the different makers

Brabham contested two further non-championship races…with the original engine in Syracuse where fuel injection problems caused a DNF and at Silverstone on May 14 where the car and engine achieved their first wins, Brabham also setting the fastest lap of the ‘International Trophy’.

First win for BT19 and the Repco ‘RB620’ engine, Silverstone International trophy 1966 (unattributed)

Monaco was the first round of the 1966 F1 Championship on May 22…

Clark qualified his small, light Lotus 33 on pole with John Surtees in the new Ferrari alongside. Jack was feeling unwell, and the cars were late arriving after a British seamens strike, Jack recorded a DNF, his Hewland HD 500 gearbox jammed in gear.

Mike Hewland was working on a stronger gearbox for the new formula, Jack used the new ‘DG300′ transaxle for the first time at Spa. Clarks’ ‘bullet-proof’ Lotus 33 broke an upright, then Surtees’ Ferrari should have won but the ‘slippery diff’ failed leaving victory to Jackie Stewarts’ 2 litre BRM P261.

Richie Ginther going the wrong way at Monaco whilst Jack and Bandini find a way past. Cooper T81 Maser, BT19 and Ferrari 246 respectively. Nice ‘atmo’ shot (unattributed)

Off to Spa, and whilst Brabham was only fourth on the grid…he was quietly confident but a deluge on the first lap caused eight cars to spin, the biggest accident of Jackie Stewarts’ career causing a change in his personal attitude to driver, car and circuit safety which was to positively reverberate around the sport for a decade.

The rooted monocoque of Jackie Stewarts’ BRM P261, Spa 1966. He was trapped within the tub until released by Graham Hill and Bob Bondurant who borrowed tools from spectators to remove the steering wheel…all the while a full tank of fuel being released…(unattributed)

Surtees won the race from Jochen Rindt in a display of enormous bravery in a car not the calibre of the Ferrari or Brabham, Jack finished fourth behind the other Ferrari of Lorenzo Bandini. Denny Hulme still driving a Climax engined Brabham.

At this stage of the season, the ‘bookies pick’, Ferrari, were looking pretty handy.

Another major new car of 1966 was the BRM P83 ‘H16’…love this shot of Jackie Stewart trying to grab hold of the big, unruly beast at the Oulton Park ‘Spring Cup’ 1966. The car got better as 1966 became 1967 but then so too did the opposition, the message of Brabham simplicity well and truly rammed home when the Lotus 49 Ford appeared at Zandvoort in May 1967…free-loading spectators having a wonderful view! (Brian Watson)

Goodyear…

Dunlops’ dominance of Grand Prix racing started with Engleberts’ final victory when Peter Collins won the British Grand Prix for Ferrari in 1958.

Essentially Dunlops’ racing tyres were developed for relatively heavy sports prototypes, as a consequence the light 1.5 litre cars could compete on the same set of tyres for up to four GP’s Jimmy Clark doing so in his Lotus 25 in 1963!

Goodyear provided tyres for Lance Reventlows’ Scarab team in 1959, returned to Indianapolis in 1963, to Europe in Frank Gardners’ Willment entered Lotus 27 F2 at Pau in 1964 and finally Grand Prix racing with Honda in 1964.

In a typically shrewd deal, Brabham signed with Goodyear in 1965, it’s first tyres for the Tasman series in 1965 were completely unsuitable but within days a new compound had been developed for Australian conditions, this was indicative of the American giants commitment to win.

By 1966 Goodyear was ready for its attack on the world championship, we should not forget the contribution Goodyears’ tyre technology made to Brabhams’ wins in both the F1 World Championship and Brabham Honda victory in the F2 Championship that same year.

Equally Goodyear acknowledged Brabhams’ supreme testing ability in developing its product which was readily sought by other competitors at a time when Dunlop and Firestone were also competing…a ‘tyre war’ unlike the one supplier nonsense which prevails in most categories these days.

Dan Gurney, Eagla T1G Climax, Spa 1966. In my top 3 ‘GP car beauties list’…Len Terry’s masterful bit of work hit its straps 12 months later when the car, by then V12 Eagle-Weslake powered won Spa, but in ’66 the car was too heavy and the 2.7/8 Climax lacked the necessary ‘puff’…Goodyear clad cameraman exceptionally brave!, shot on exit of Eau Rouge (unattributed)

The French Grand Prix was the turning point of the season…

Brabham arrived with three cars- Hulmes’ Climax engined car as a spare and finally an ‘RB620’ engined car for the Kiwi. Perhaps even more critically for Brabham, John Surtees had left Ferrari in one of the ‘Palace Upheavals’ which occurred at Maranello from time to time, fundamentally around Surtees’ view on the lack of F1 emphasis, the team still very much focussed on LeMans and the World Sports Car Championship, where the marques decade long dominance was being challenged by Ford.

Surtees was also, he felt, being ‘back-doored’ as team-leader by team-manager Eugenio Dragoni in choices involving his protege, Lorenzo Bandini. The net effect, whatever the exact circumstances was that Surtees, the only Ferrari driver capable of winning the ’66 title moved to Cooper, Bandini and Mike Parkes whilst good drivers were not an ace of 1964 World Champ, Surtees calibre…

Reims was the ultimate power circuit so it was not a surprise when four V12’s were in front of Brabham on the grid, the Surtees and Rindt Coopers and the two Ferraris. Surtees Cooper failed, and Jack hung on, but was losing ground to Bandini, until his throttle cable broke with Brabham leading and then winning the race.

It was Jacks’ first Championship GP win since 1960, and the first win for a driver in a car of his own manufacture, a feat only, so far matched by Dan Gurney at Spa in 1967.

It was, and is a stunning achievement, but there was still a championship to be won.

Brabham wins the French GP 1966, the first man to ever win a GP in a car of his own construction. Brabham BT19 Repco (umattributed)

Brabham’s BT19 leads out of Druids at Brands Hatch, ’66 British GP. Gurney Eagle T1G Climax, Hulme’s Brabham BT20 Repco, Clark’s Lotus 33 Climax and the two Cooper T81 Masers of Surtees inside and Rindt, then Stewart’s BRM P261 and McLaren’s white McLaren M2B Serenissima and the rest (unattributed)

At Brands Hatch Ferrari did not appear…

They were victims of an industrial dispute in Italy. Cooper were still sorting their Maser V12, the H16 BRM’s did not race nor did the Lotus 43, designed for the BRM engine. BRM and Lotus were still relying on 2 litre cars. Brabham and Hulme were on pole and second on the grid, finishing in that order, a lap ahead of Hill and Clark.

At Zandvoort, in the Dutch sand-dunes…

Jack was tough but had a sense of humor…he had just turned 40 a month or so before, there was a lot in the press about his age so JB donned a beard, and with a jack-handle as walking stick approached BT19…much to the amusement of the Dutch crowd and press (Eric Koch)

Brabham and Hulme again qualified one-two but Jim Clark drove a stunning race in his 2 litre Lotus leading Jack for many laps, the crafty Brabham, just turned forty playing a waiting game and picking up the win after Clarks’ Climax broke its dynamic balancer, the Scot pitting for water and still being in second place when he returned, such was his pace. Clark fell back to third, Hill finishing second, the Ferraris and Coopers off the pace.

Bernard Cahiers’ famous shot of Brabham ‘playing with his Goodyears’ in the Dutch sand-dunes is still reproduced by Repco today and used as a ‘promo’ handout whenever this famous car, Jacks’ mount for the whole of his ’66 Championship campaign, still owned by Repco, is displayed in Australia

German GP grid, Nurburgring 1966. I like this shot as it says a lot about the size of 1966 F1 cars and the relative performance of the ‘bored-out 1.5 litre cars vs. the new 3 litres at this stage of the formula. The only 3 litre on the front row, is Ferrari recent departee John Surtees Cooper Maserati #7, Clark is on pole #1 Lotus 33 Climax, #6 Stewart BRM P261, # 11 Scarfiotti Ferrari Dino, all ‘bored 1.5’s. Row 2 is Jack in BT19, and #9 and #10 Bandini and Parkes in Ferrari 312’s, all ‘3 litres’. The physical difference in size between the big, heavy Ferraris, and the little, light BT19 ‘born and built’ as a 1965 1.5 litre car for the stillborn Coventry Climax Flat 16 engine, is marked (unattributed)

The Nurburgring is the ultimate test of man and machine…

Brabham qualified poorly in fifth after setup and gearbox dramas. Clark, Surtees, Stewart and Bandini were all ahead of Jack with only Surtees, of those drivers in a 3 litre car!

The race started in wet conditions, Jack slipped into second place after a great start by the end of lap one and past Surtees by the time the pack passed the pits, Surtees suffered clutch failure widening the gap between he and Brabham, Rindt in the other Cooper finishing third. Hulme was as high as fifth but lack of ignition ended his race.

Hill and Surtees were still slim championship chances as the circus moved on to Monza.

Denny and Jack ponder the setup of Hulmes BT20, practice conditions far better than raceday when Jack would triumph (unattributed)

Ferrari traditionally perform well at home…and so it was, Ludovico Scarfiotti winning the race on September 4.

Another power circuit, Brabham was outqualifed by five ‘multis’ the V12’s, the Ferraris of Parkes (pole) Scarfiotti and Bandini, the Cooper of Surtees and the H16 Lotus 43 BRM of Clark in third.

The Ferraris lead from the start from Surtees, but Brabham sensing a slow pace took the lead only losing it when an inspection plate loosened at the front of the engine, burning oil, the lubricant not allowed to be topped up under FIA rules. Hulme moved into second as Jack retired. The lead changed many times but Surtees retirement handed the titles to Brabham, Scarfiotti winning the race from Parkes and Hulme.

The cars were scrutineered and weighed at Monza.

The weights of the cars was published by ‘Road and Track’ magazine. BT19 was ‘Twiggy’ at 1219Lb, the Cooper T81 1353Lb, BRM 1529Lb, similarly powered Lotus 43 1540Lb and Honda RA273 1635Lb. Lets say the Repcos’ horses were real at 310bhp, Ferrari and Cooper (Maserati) optimistic at 360 and BRM and Honda 400’ish also a tad optimistic…as to power to weight you do the calculations!

Jim Clark jumps aboard his big, beefy 1540Lb Lotus 43 BRM whilst Jacks light 1219Lb BT19 is pushed past, ’66 Monza grid. Love the whole BRM ‘H16’ engine as a technical challenge…(unattributed)

2 of the ‘heavyweights’ of 1966, Ludovico Scarfiottis’ Ferrari 312 leading Jim Clarks’ Lotus 43 BRM at Monza, Scarfiottis’ only championship GP win (unattributed)

Jim Clarks’ Lotus 43 BRM achieved the ‘H16’s only victory at Watkins Glen…the Scot using BRM’s spare engine after his own ‘popped’ at the end of US Grand Prix practice. Jack’s engine broke a cam follower in the race, Denny also retiring with low oil pressure.

Front row of the Watkins Glen grid. #5 Brabham’s BT20 on pole DNF, Bandini’s Ferrari 312 DNF and Surtees Cooper T81 Maser 3rd (Alvis Upitis)

The final round of the 1966 was in Mexico City on October 23…

The race won by John Surtees from pole, in a year when he had been very competitive, and perhaps unlucky. Having said that, had he stayed at Ferrari perhaps he would have won the title, the Ferrari competitive in the right hands. Brabham was fourth on the grid, best of the non-V12’s with Richie Ginther again practicing well in the new, big, incredibly heavy V12 Honda RA273. Surtees’ development skills would be applied to this car in 1967.

Surtees finished ahead of Brabham and Hulme, despite strong pressure from both, whilst Clark was on the front row with the Lotus 43, the similarly engined BRM’s mid-grid, it was to be a long winter for the teams the postion of many not that much changed from the seasons commencement…

John Surtees, Jack and Jochen Rindt, Coopers T81 Maserati X2 and BT19. Mexican GP 1966. Ferrari missed Surtees intense competitiveness when he left them, the Cooper perhaps batting above its (very considerable!) weight as a consequence, Rindt no slouch mind you. The Coopers’ competitive despite the tough altitude and heat of Mexico City. (unattributed)

Malcolm Prestons’ book ‘Maybach to Holden’ records that 3 litre engines ‘E5, E6, E7 and E8’…were used by BRO in 1966, in addition to E3, all having at least one replacement block.

Some engines were returned to Melbourne for re-building and at least three were sold in cars by Brabham to South Africa and Switzerland, whether Repco actually consented to the sale of these engines, ‘on loan’ to BRO is a moot point!, but parts sales were certainly generated as a consequence.

Detail development of the ‘RB620’ during the season resulted in the engines producing 310 bhp @ 7500rpm with loads of torque and over 260bhp from 6000-8000rpm.

Back In Australia…

The Tasman ‘620’ 2.5 litre engine was not made available to Australasian customers in 1966, they were in 1967, a Repco prepared Coventry Climax FPF won the ‘Gold Star’, the Australian Drivers Championship in 1966, Spencer Martin winning the title in Bob Janes’ Brabham BT11A.

4.4 litre ‘RB620′ engines were built for Sports Cars, notably Bob Janes’ Elfin 400, we will cover those in a separate chapter.

Development of the F1 engine continued further in early 1966 in Maidstone, whilst production and re-building of the ‘RB620’ for BRO continued, we will cover the design and testing of what became the 1967 ‘RB740′ Series engine in the next episode…

Meanwhile Brabhams’, Tauranacs’, Irvings’ and Repcos’ achievements were being rightly celebrated in Australia where ingenuity, practicality and brilliant execution and development of a simple chassis and engine had triumphed over the best of the established automotive, racing and engineering giants of Europe…

Etcetera…

Jack Brabham and Denny Hulme, 1st and 4th in the World Drivers Championship 1966. Mexican GP 1966, lovely Bernard Cahier portrait of 2 good friends. Graham Hills’ BRM P83 ‘H16’ at rear.

A fitting photo to end the article…the joy of victory and achievement after his Rheims, French GP victory. The first man ever to win a GP in a car of his own manufacture, Brabham BT19 Repco (unattributed)

Bibliography…

Rodway Wolfe Collection, ‘Jack Brabhams World Championship Year’ magazine, Motoring News magazine, The Nostalgia Forum, oldracingcars.com, Nigel Tait Collection

‘Maybach to Holden’ Malcolm Preston, ‘History of The Grand Prix Car’ Doug Nye

Photo Credits…

The Cahier Archive, Brian Watson, Tyler Alexander, Ellis French, Eric Koch, Alvis Upitis, Rodway Wolfe Collection

Tailpiece: The Repco hierachy at Sandown upon the RB620’s Australian debut, 27 February 1966. Phil Irving leaning over BT19 and trying to grab another fag from Frank Hallam’s packet. Norman Wilson with head forward leaning on the rear Goodyear, Kevin Davies and Nigel Tait in the white dust coat…and Jack wishing they would bugger ‘orf so he could test the thing. Nigel Tait recalls that the car probably had 2.5 engine #E2, had no starter motor and he the job of push-starting the beastie…